The Transit of Venus

Jamie Barras

In 1874, the British government sent expeditions around the world to observe the transit of Venus. The party dispatched to the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi travelled there on the steam corvette H.M.S. Scout. A year earlier, the crew of the Scout had played a game of baseball against the crews of the U.S.S. Pensacola and Omaha at Coquimbo in Chile; they lost 37–12, the only member of the team having any experience of the game being the ship’s assistant navigator, Sub-Lieutenant Richard Harriman Wellings (1851-1913). On arrival in Hawaiʻi for the transit observation, the Scout's crew, again led by Wellings, took another crack at the game, this time against the crew of the U.S.S. Benicia; they lost again, but this time, the result was much closer, 42–39.[1]

These two games, a year and 7000 miles apart, highlight the unlikely role that Britons played in spreading baseball across the Pacific in the 1870s, a role that was to have an equally unlikely sequel in England 20 years later.

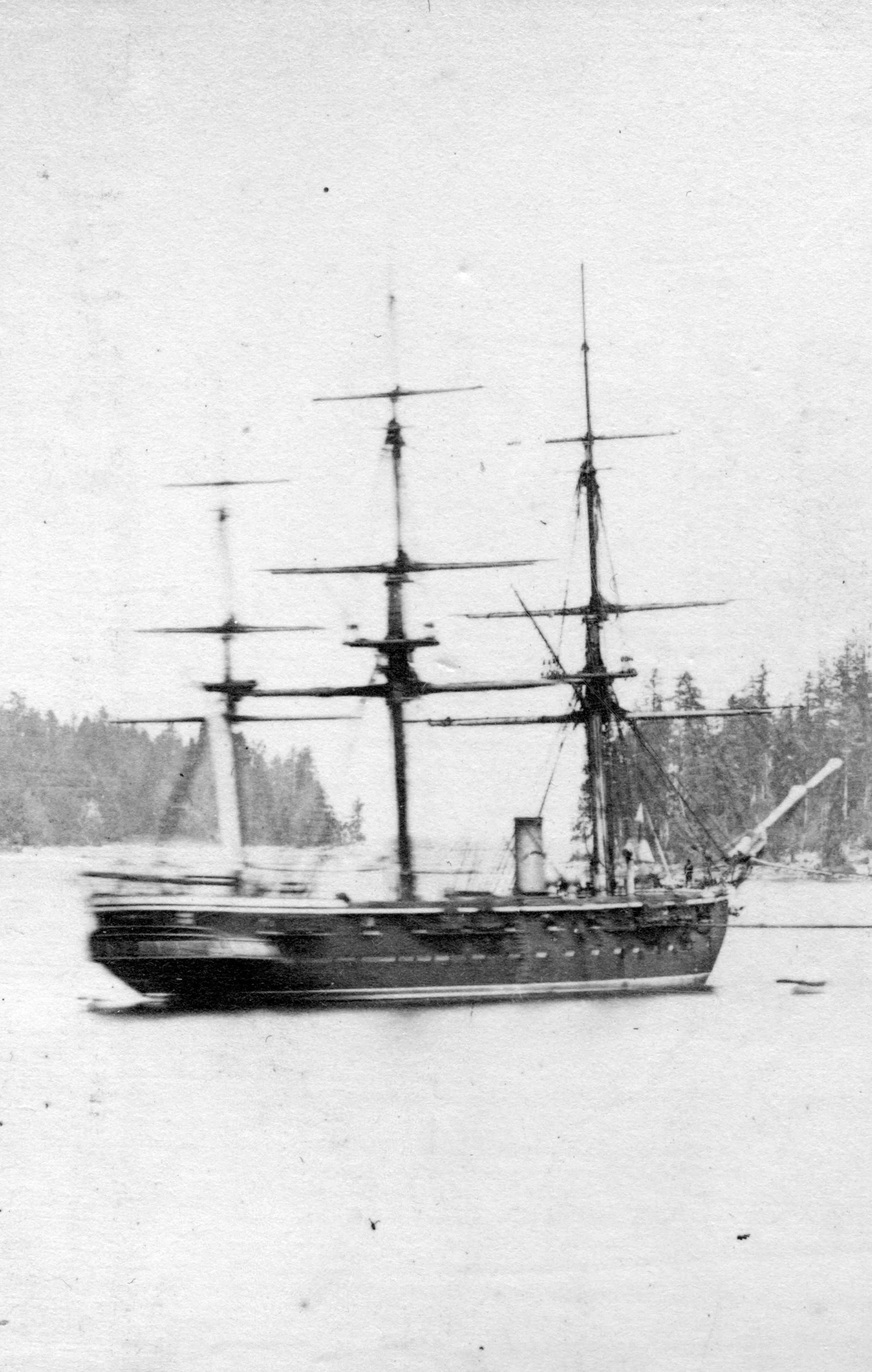

SCOUT, 17, screw-corvette. A correspondent writing from Coquimbo, Chili, on September 4th, says:—" A very pleasant game at 'base ball' was played between the officers of this ship and the officers of the U.S. ships Pensacola (flag) and Omaha, resulting in a victory for the latter. However, nobody expected otherwise, as 'base ball' is the national game of the Americans, and only one of the Scout's team (Mr. Wellings) had ever played the game before[...]"[2]

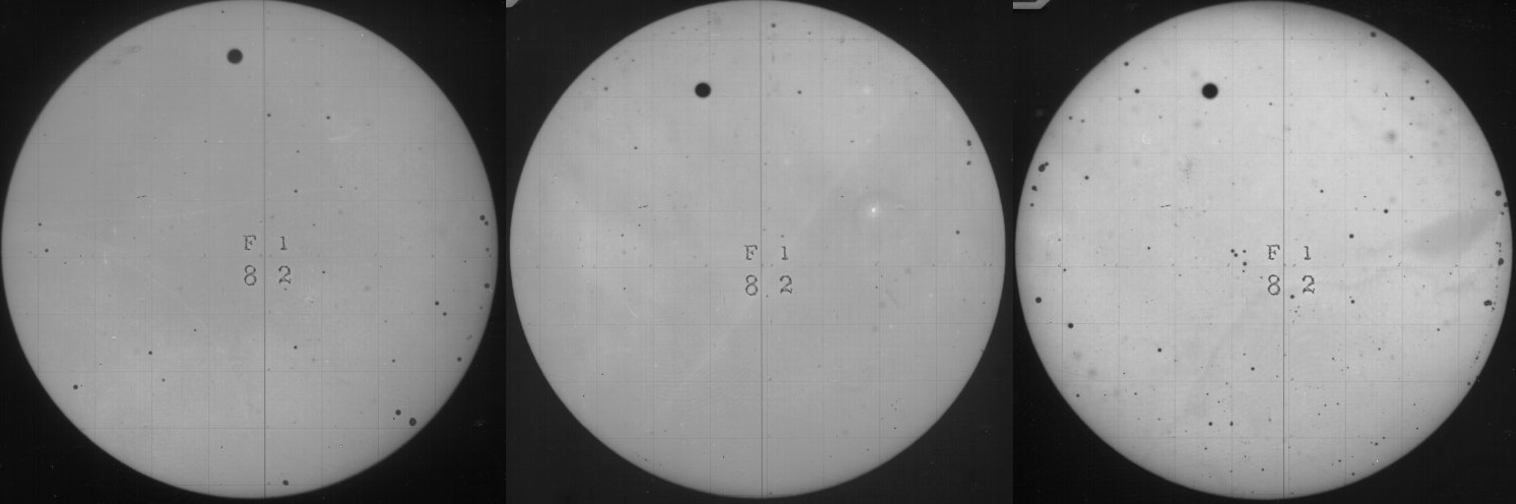

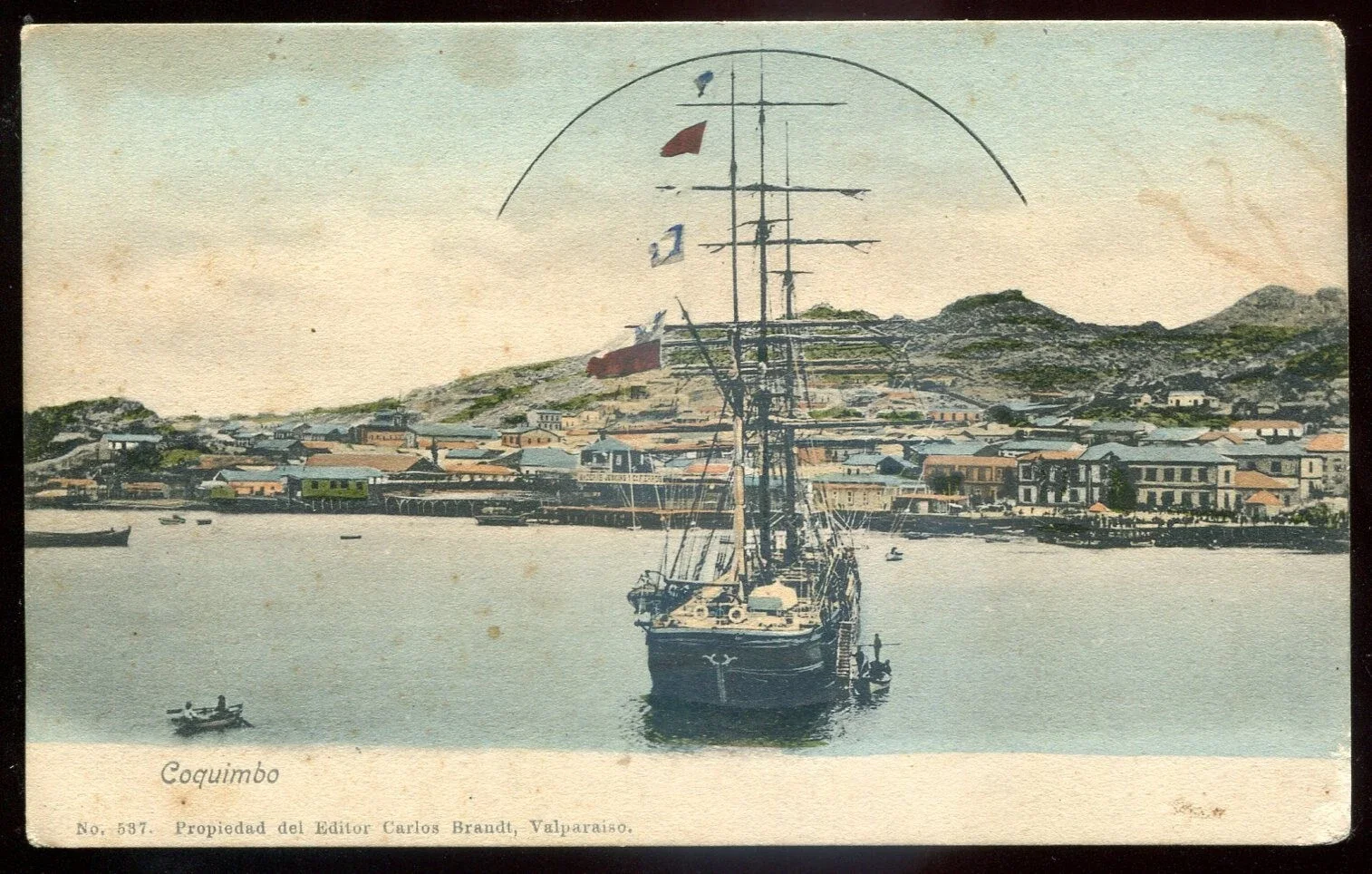

The Scout, under the command of Captain Ralph Peter Cator (1829–1903), was two years into a grueling four-year posting to the Pacific Station when she dropped anchor in Coquimbo, Chile, in August 1873.[3] Launched in 1856, the Scout was wooden-hulled but propelled by a steam-driven screw propeller. In this era of rapid advances in naval architecture, she was already obsolete by the time she reached the Pacific and would be decommissioned on her return to England in June 1875.[4]

At Coquimbo, Scout’s crew took on the crews of the Pensacola and Omaha of the US Navy’s South Pacific Station in friendly games of not only baseball but also cricket, losing the former and winning the latter, a pattern that was reproduced in the many encounters between Britons and Americans on sports fields all across the world in this period.[5] Although very early in the history of baseball and quite early in the history of cricket in South America, these were not the first games of either sport played in Chile. Valparaiso even boasted its own baseball and cricket clubs—the Scout would be back in Chile in the summer of 1874; while there, it would take on Valparaiso at cricket.[6]

The writer of the letter reporting the Scout’s Coquimbo games included team lists; the baseball game rosters are reproduced below.

The players were.—H.M.S. Scout.— Mr. R. H. Wellings (captain), Lieutenant Clutterbuck, Lieutenant Ford, R.M.L.1., Messrs. Sandiford, Hume, Ledgard, Trower, Fraser, and Tottenham. U.S. ships Pensacola and Omaha. —Mr. Febiger (captain), Lieutenant-Commander Nichols, Lieutenant Ackley, Messrs. Hadden, Schwenk, Barber, Miles, McCrea, and Steedman."[7]

The team members were all officers, mostly midshipmen. We can identify William R. Clutterbuck (1844–1923), Edward A. Ford (?–1875), Edward J.J.H. Sandiford (1851–1930), Charles B.P. Hume (1852–1895), John Ledgard (1853–?), Cornwallis J. Trower (1854–1881), John A.M. Fraser (1854–?), and Francis E.J. Tottenham (1854–1889).[8] Most significantly for our story, “R.H. Wellings”, identified by the letter writer as the only member of the Scout’s team who “had ever played the game before”, we can identify as Sub-Lieutenant Richard Harriman Wellings (1851-1913).

Born in Leicestershire, the son of a doctor, Wellings grew up in Hampshire. It was almost inevitable, given where he spent his childhood, that Wellings would join the Royal Navy. He became a Royal Navy cadet in 1864 and graduated a master’s assistant in 1866—this being a rank specifically associated with the navigation branch of the service. Wellings was of a mathematical turn of mind.[9]

In May 1869, Wellings was made a midshipman (navigating) and appointed to H.M.S. Monarch. Launched the year before, the Monarch represented a revolution in naval design. An ironclad, she was the first ship in the Royal Navy with her main armament mounted in turrets, and the first naval ship in the world equipped with 12-inch guns. The real significance of Wellings’ appointment to the Monarch for our story, however, is that, in January 1870, the Monarch was chosen to carry the body of Massachusetts-born philanthropist George Peabody back to the USA.[10]

Born into poverty in 1795, Peabody went on to amass a fortune through trade, real estate dealings, and finance. He spent much of his later life in England, and after he retired, devoted himself to philanthropy. His name lives on in England in the form of the Peabody Trust social housing association. Such was his reputation in England that on his death in November 1869, Prime Minister W.E. Gladstone instructed that his body be conveyed to America for burial on board the Monarch, the Royal Navy’s newest and most-advanced warship. Of course, the show of strength involved in having arguably the world’s most powerful warship appearing off the shores of America with the Union Jack flying from its mainmast was not lost on Gladstone; nor were officers of the cash-strapped US Navy slow to see how the presence of such a vessel in US waters could be turned to their advantage.[11]

THE BRITISH IRON-CLADS. There is great interest felt among navy officers here in reference to the British iron clad Monarch, in view of the declaration of Captain Macomb of the U.S. steamer Plymouth, that consorted the Monarch across the Atlantic, that she is the greatest iron-clad vessel for the ocean in the world[…]A reliable and prominent naval officer declared, “they can sweep us off the seas. We have nothing to compete with them, yet Congress will not allow our vessels to be altered or new ones to be constructed.”[12]

The Monarch arrived at Portland, Maine, on 27 January 1870 and remained in US waters until 23 February, spending the last week of its visit anchored at the US naval base at Annapolis, Maryland, where it hosted visits from US government officials from nearby Washington, DC. During their stay, the officers and crew of the Monarch were wined and dined up and down the Eastern seaboard.[13]

There is no suggestion that the crew of the Monarch took part in or even got to see a game of baseball—this was February, after all—however, we can suppose that the merits of the game compared to cricket were much discussed, if only in the spirit of gentle joshing with the officers and men of the US Navy with whom the crew of the Monarch socialised. If we are looking for an event that separates Richard Wellings from the rest of the crew of the Scout that might explain why, in 1873, he had played baseball, and they had not, we need look no further than those 3 weeks he spent in the USA as the inciting incident. The opportunity to play the game for himself would come with his next assignment.

THE SCOUT was in the Straits yesterday morning; she returned to Esquimalt harbor at noon.[14]

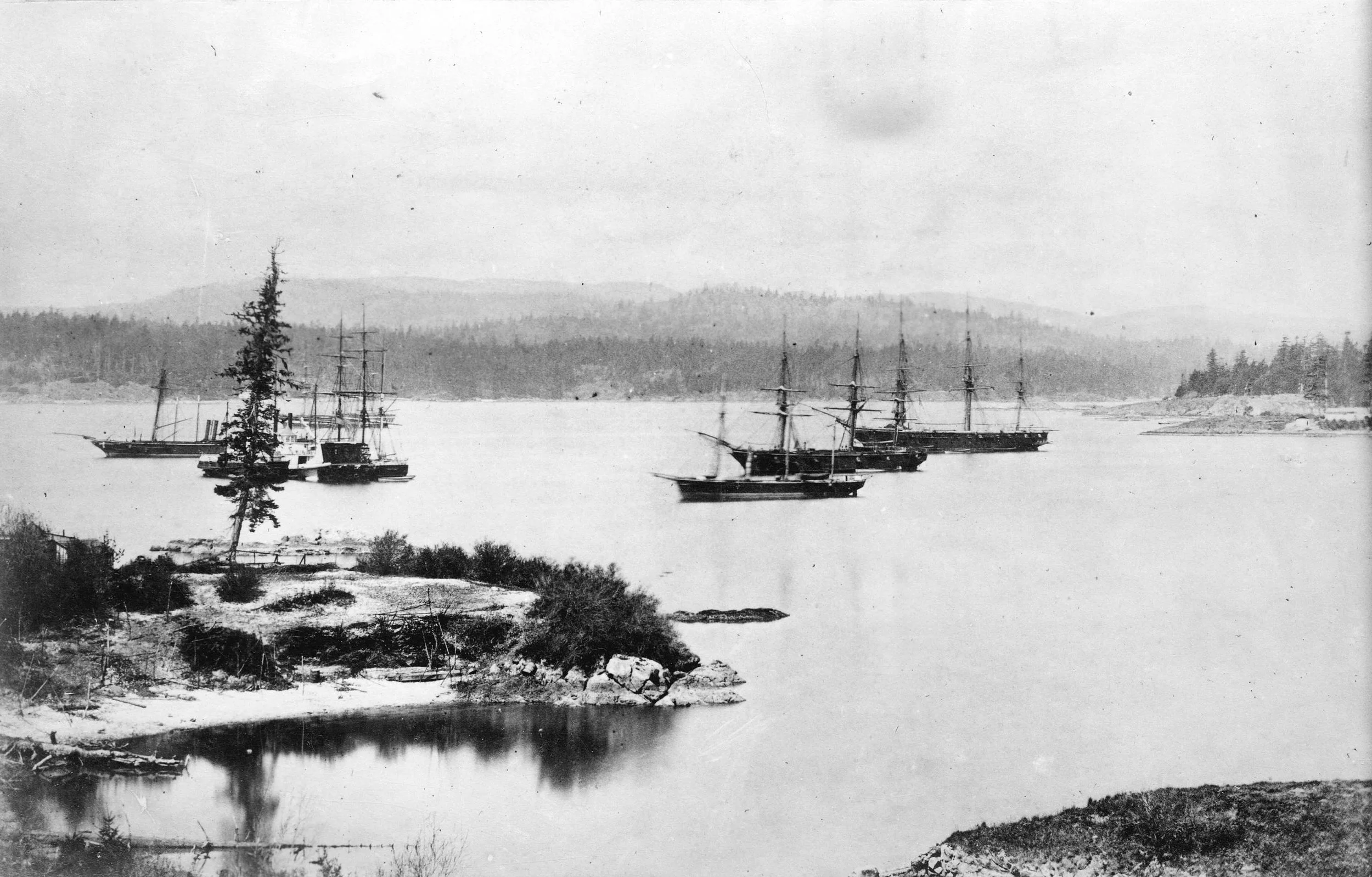

Esquimalt Harbour, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, immediately west of the provincial capital, Victoria, was made the headquarters of the Royal Navy’s Pacific Station in 1865. It was to be H.M.S. Scout’s home port for the first two years of its 1871–1875 Pacific cruise. Richard Wellings had joined the Scout after returning to England with the Monarch. In October 1870, he was promoted to Navigating Sub-Lieutenant and made the Scout’s assistant navigating officer. In March 1871, the Scout departed England for the Pacific via the Magellan Strait. With stops along the way at Madeira, Rio de Janeiro, and the Falkland Islands, she reached her station in the early autumn.[15]

The baseball scene in Victoria in the early 1870s was small but lively, built, as was much in the social life of Vancouver Island, on rivalry with American teams in the towns of the Washington Territory (W.T., future State of Washington), on the other side of the Juan de Fuca Strait.

BASE BALL.—We understand the Olympics of Victoria, which are about to reorganize, have sent a challenge to the clubs at Olympia, W.T., to play a game of base ball in the city, on the Queen’s Birthday next, and to play a return march on the 4th of July, at Olympia. The club in this city will have a practice game at Beacon Hill, on Saturday next.[16]

Even though the crew of the Scout played cricket against the crews of other Royal Navy vessels of the Pacific Station while at Vancouver Island,[17] we can suppose that they did not play baseball against local teams, as, before the game in Coquimbo in October 1873, Richard Wellings was the only member of the Scout nine who had experience of the game. In identifying what set Wellings apart from his shipmates, we can only point to those 3 weeks he spent in America in February 1870 while serving on the Monarch. It seems likely that Wellings heard or saw enough about baseball on that short visit to the US that, when the opportunity to try the game for himself arose on the Scout’s arrival at Vancouver Island, he availed himself of it. Not that he would have much time for leisure activities of any kind, as the Scout was to have a busy time in the Pacific.

On Sunday last at half past eleven o’ clock, Her Majesty Queen Emma, accompanied by Mrs. Colonel Pratt and Miss Peabody, attended divine service on board H.B.M.’s Ship Scout. Hon. Mrs. Bishop, His Excellency the Governor of Oahu and Hon. Mrs. Dominis were also on board the Scout at the same time. After the service, Captain Cator entertained Her Majesty and his other Guests at an elegant lunch. The Scout sailed for Esquimalt, B.C., at four o’clock on Sunday afternoon.[18]

Although the Scout was to play a walk-on part in the final act of the infamous Pig War, evacuating the Royal Marine garrison from San Juan Island in November 1872,[19] unquestionably, both for our story and history, the most important missions that she undertook were her three visits to the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in 1872, 1873, and 1874. The last and longest of those trips, we will cover in depth. The first, in April and May 1872, was simply a three-week “courtesy call” and included Captain Cator and his senior officers being presented at court to King Kamehameha V and later hosting the Dowager Queen Emma.[20] The second, which began in January 1873 and lasted several months, was different; it was a show of force, directed not at the newly elected King Lunalilo and his court but at the United States of America.

The California, flying the broad pennant of Admiral Pennock, came in the other day, and now lies in the harbor, with the Benicia on one side, and H.B.M. corvette Scout on the other. Just what the Scout came for no one knows. It is shrewdly surmised that the Scout was sent here to protest against Uncle Sam taking possession.[21]

The death of King Kamehameha V in December 1872 brought to an end the dynasty that, in 1795, had forcibly united the Hawaiian Islands to form the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. From its creation, the kingdom had played host to the competing interests of Britain and the USA, a rivalry fueled by the kingdom’s increasing importance as a trading hub and producer and exporter of sugar. Added to this was the complicated interplay between British and American missionaries in the kingdom.[22]

King Kamehameha V died without an heir, triggering a constitutional crisis. The British commissioner of Hawaiʻi and his French counterpart had tried unsuccessfully to persuade the king to appoint a successor to avoid just such a period of uncertainty. This was for fear of affording the United States an excuse to intervene, a move that the commissioners judged would be “fatal to Hawaiian independence”.[23]

In the event, the Hawaiian government, recognising the danger, moved so swiftly that, by the time that Rear Admiral Alexander M. Pennock, commander-in-chief of the US North Pacific Squadron, steamed into Honolulu harbour on 17 January 1873 with two ships, he was not only followed into port by the Scout, but also confronted with the news that a popular vote had been held, subsequently ratified by the Hawaiian legislature, that had elevated William C. Lunalilo to the throne. Faced with this fait accompli, Pennock made nice with the new regime, opening negotiations for a new reciprocal treaty that would allow the US to build a naval base on an area of the coast known as Pearl Bay. The Scout lingered at Honolulu for two months, perhaps to cement relations with the new regime, perhaps to keep an eye on Pennock and his Uncle Sam. She departed finally on 29 March 1873. She would return.[24]

GREAT STORM AT VALPARAISO. A great gale from the northward had visited Valparaiso and its adjoining coasts. H.M.S. Scout, that was lying at Valparaiso, parted from her cables and had to steam to sea.[25]

The Scout spent much of 1873 stationed in Chile. Home to rich nitrate deposits and a large expatriate British community, with the port of Coquimbo being a British town in all but name, and Valparaiso being a former headquarters of the Royal Navy’s Pacific Station, Chile was arguably second only to British Columbia in territories of the Eastern Pacific Rim of importance to the British.[26]

It was in Coquimbo on 27 August 1873 that Richard Wellings captained a Scout nine in a game of baseball against a team formed of sailors from the U.S.S. Pensacola and Omaha. The Pensacola was the flagship of Rear Admiral Charles Steedman, commander-in-chief of the US Navy’s South Pacific Squadron. Like Pennock, his counterpart in the North Pacific Squadron, Steedman had served in the Union Navy in the American Civil War. This is remarkable in Steedman’s case, as he was a native of Charleston, South Carolina. His war service included commanding the blockade of his hometown. Many of the blockade runners that Steedman and his fellow Union Navy captains were on the hunt for were built in British shipyards and crewed by British sailors; their officers were often Royal Navy officers on half pay. In August 1863, one such blockade runner, the Bristol-built Juno, making for Charleston, was captured after a long chase by a Union gunboat. The name of Juno’s captain? Ralph Peter Cator, Royal Navy officer on half pay, and future captain of the Scout.[27]

Did Steedman and Cator reminisce about their days as adversaries when the Scout and the Pensacola were both anchored at Coquimbo in the summer of 1873?

Two very pleasant days were spent, each of the competitors winning their own national game. The Pensacola left for Panama on Sept. 1st, and the Omaha left for Valparaiso on the 2nd. H.M.S. Scout is likely to remain another month or six weeks at Coquimbo, and will then probably go to Juan Fernandez.[28]

Without the issue of the possible annexation of an ally (the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi) by their opponents to worry about, relations between the Royal Navy and US Navy in Chile were cordial, bordering on friendly (arguably, relations between sailors of the navies of rival powers were ever so, irrespective of how cold or hot tensions were between their governments—this is something that would come up again in Hawaiʻi, as we will see).

Although Richard Wellings may not have been the first to suggest that the crews of the Scout, the Pensacola, and the Omaha play each other at their “national games”, we can be sure that it was knowing that they had on board someone who could teach is fellow officers the rudiments of the American national game would have at least suggested to Captain Cator that the Scout nine could enter the field without fear of embarrassing themselves too greatly. Meanwhile, the US Navy of the time included British-born sailors in its ranks; the Pensacola and Omaha likely had cricket instructors enough—we know that this was the case when the Scout nine met a Bernicia nine the following year. It is worth noting in this regard that, although the Scout eleven made easy work of the Americans in the cricket match played 2 days after the baseball game, the Britons came away from that match impressed by at least one aspect of the novice cricketers' play.

The fielding of the Americans was very good indeed, and their throwing in was almost perfect.[29]

The high quality of the fielding of American baseball players was often remarked upon by British observers in this period. Indeed, within three years of the Coquimbo game, back home in England, a group of English cricketers would take up baseball as a winter sport specifically to improve their fielding skills.[30]

Although the result was a foregone conclusion, we can suppose that Richard Wellings at least came away from the Coquimbo game believing that with just a little more practice, the Scout nine would be able to give the next US Navy nine it encountered a run for its money. It would be another year before he would have a chance to test that belief.

THE TRANSIT OF VENUS. A telegram has been received from Captain Cator, of H.M.S. Scout, at Valparaiso, stating that the expedition for the observation of the transit of Venus started on their errand on the 4th August.[31]

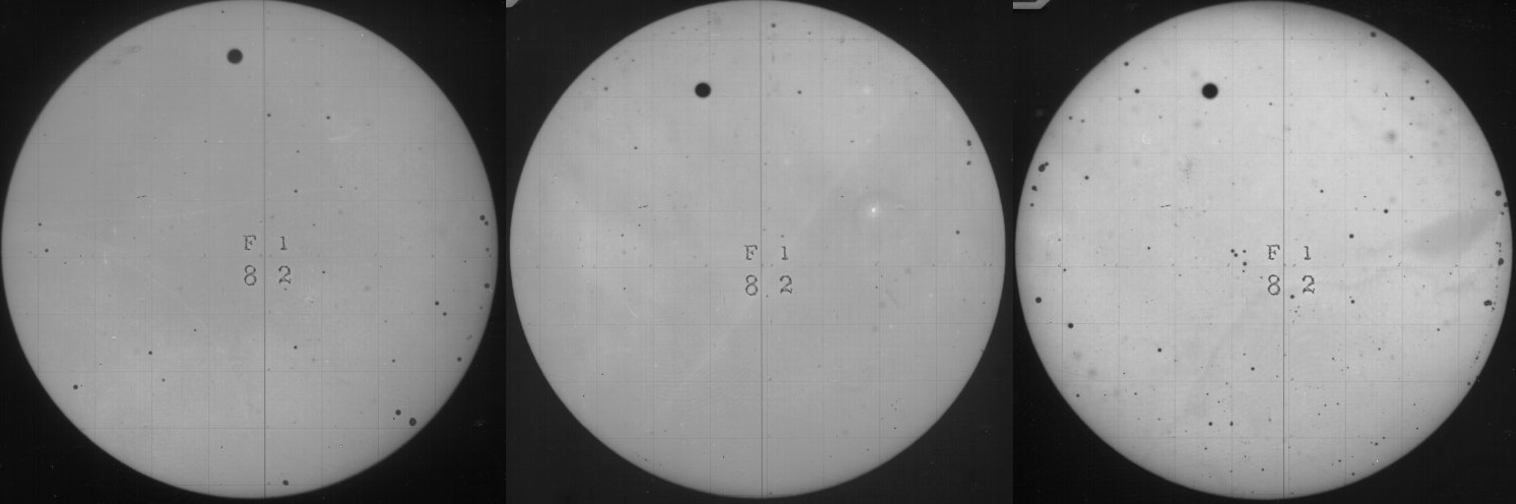

The transit of Venus is the name given to the phenomenon that occurs when the positions of the Sun, Venus, and Earth align such that, from the point of view of an observer on Earth, Venus appears to pass directly in front of the Sun. It was Edmund Halley who, in the 18th Century, building on the work of others, first proposed that measuring the time it took Venus to cross from one side of the solar disk to the other from different points on Earth could allow the distance from Earth to Venus to be accurately calculated. This, by extension, would allow the distance from Earth to the Sun, which was used as a yardstick for all other solar system measurements, to be calculated.[32]

For the 1874 transit, the Royal Observatory at Greenwich sent out expeditions to five widely spaced locations across the globe: Egypt, Rodriguez Island, New Zealand, Kerguelen Island, and the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. The expedition bound for Hawaiʻi set out from Liverpool in June 1874 in two Pacific Steam Navigation Company ships, the Illimani and the Britannia. Arriving in Valparaiso via the Magellan Straits in late July, the expedition personnel and equipment were transhipped to H.M.S. Scout. The Scout set sail from Valparaiso on 4 August 1874, arriving at Honolulu a month later after a stormy passage.[33]

The main observatory for the transit would be established at Honolulu on Oahu. There were two further substations established at Kailua on Hawaiʻi itself and Waimea on Kauai. Richard Wellings would be the senior naval officer assigned to the Waimea substation and leave Honolulu to take up that task in early November 1874.[34] However, before then, there was the small matter of a rematch with the US Navy on the baseball diamond.

BASE BALL AND CRICKET BY THE SAILORS.—A “team” of players from each of the war vessels in port,—the U.S.S. Benicia, and H.B.M.’s Scout—have had one or two friendly contests of the above games during the past month on the plains east of the city, and the meetings have been noteworthy as conducive of a fraternal feeling between the seamen of the two nationalities.[35]

Although these games undoubtedly owed their existence to the Scout’s contests against the Pensacola and Omaha the previous year, they took place just a few months after English cricket clubs and American baseball teams had faced each other at cricket in England. This was during the 1874 tour of England by the Boston Red Stockings and Philadelphia Athletic Base Ball Clubs, organised and led by Harry Wright. The Hawaiian press published an account of the tour in early September and again in early November. It being known in Honolulu that American baseball players and English cricketers had faced each other in England may well have helped Wellings when it came time to issue the challenge to the Benicia. As an aside, the high quality of the fielding by American baseball players was again a feature of newspaper accounts.[36]

Alas, although Frederick Strath, Master at Arms of the Scout, furnished the Hawaiian press with an account of the contests against the Benicia, the newspapers chose not to publish it.

We can find room only for the total of scores, by which it will be observed that each nation was the conqueror in its own game—the Americans at base-ball and the Britons at cricket. Base Ball, Oct. 15. Benicia’s innings, 42; Scout’s 39. Cricket, Oct. 22. First innings,—Scout 78; Benicia 48. Second innings—Scout, 113; Benicia, 33.[37]

While this game was almost certainly the first time that a British nine took on an American nine in Hawaiʻi, it was far from being the first game of baseball played in the kingdom, nor was it the first to feature players of British and American descent.

Game of Ball. Quite an interesting game of ball came off yesterday afternoon on the Esplanade between the Punahou Boys and the Town Boys. The game was so good and so good [sic] when our reporter left the scene of the action. The “boys” of a larger growth, among whom were some of the leading merchants and their clerks, had a game of good old-fashioned base ball on Sheriff Brown’s premises, makai, which is said to have afforded much amusement both to actors and spectators. Success to the “sport”.[38]

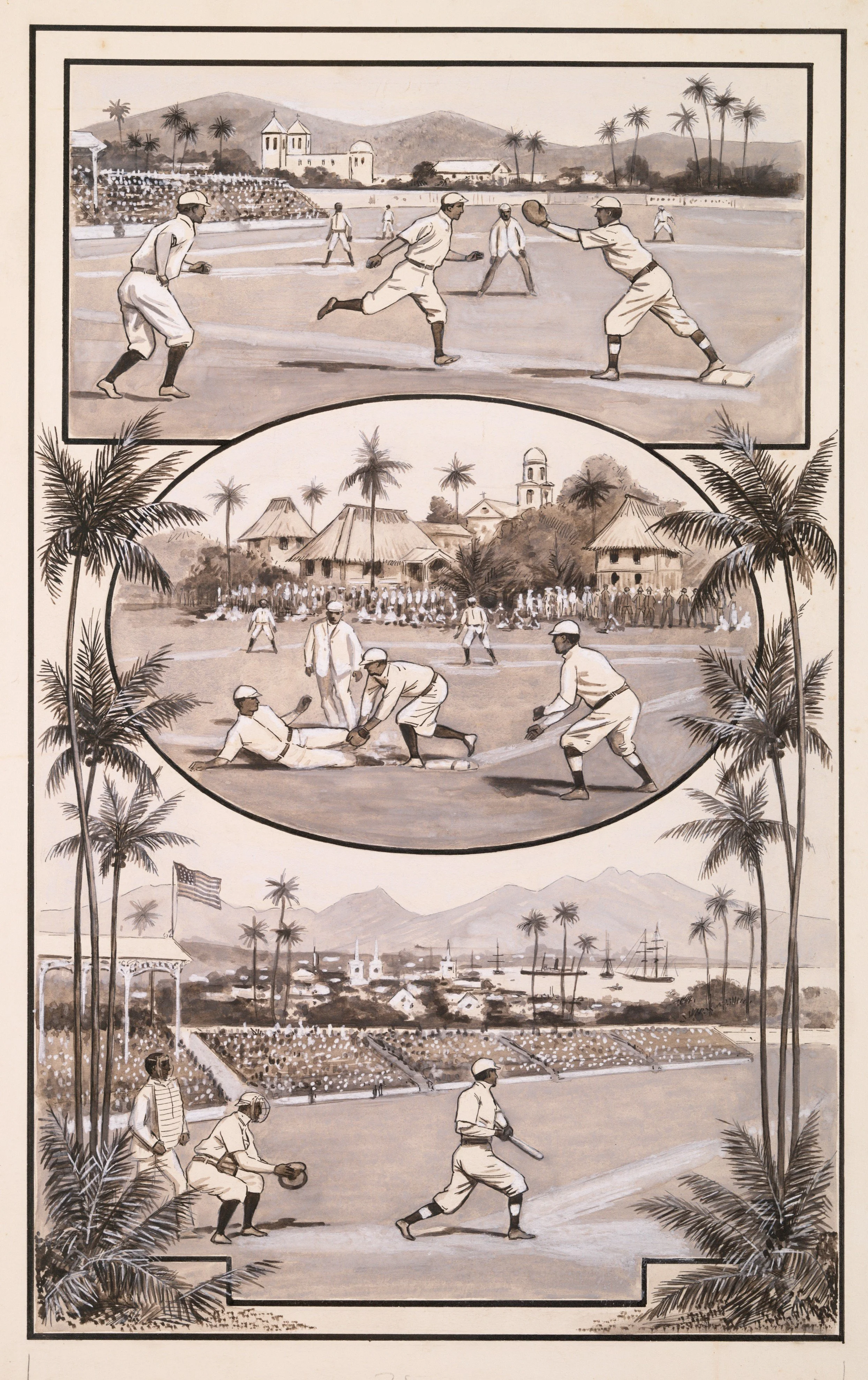

The origins of baseball in Hawaiʻi are disputed, although the scholarly view is that the organised game was introduced to the kingdom in the late 1850s by the staff and students of the Punahou Preparatory School in Honolulu. Certainly, the earliest press reports of the game in the kingdom date from this period and involve the Punahou School. The alternative, populist, but almost certainly incorrect, story is that the organised game was introduced to the kingdom by Alexander Cartwright Jr, founder member of the New York Knickerbockers Base Ball Club and inaugural inductee into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Cartwright moved to Hawaiʻi with his family in 1849, and many years later, one of his grandchildren would tell Albert Spalding that Cartwright began teaching locals the game soon after his arrival and laid out the kingdom’s first diamond at Makiki, Honolulu, in 1852. Scholars have been unable to find convincing evidence of Cartwright being involved in baseball in any way in Hawaiʻi, although two of his sons, both graduates of the Punahou School, unquestionably did play the game.[39]

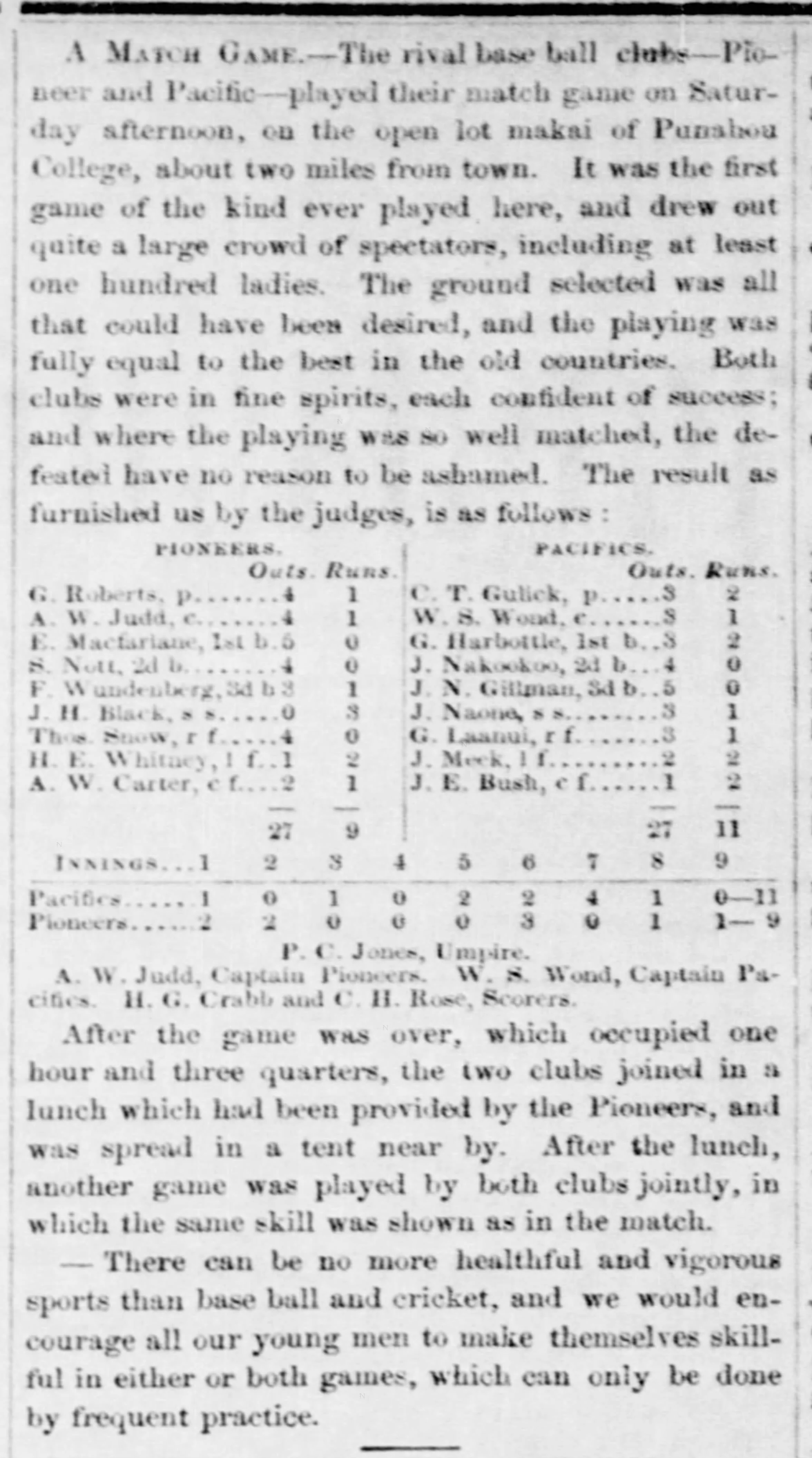

The Punahou School was founded and run by New England missionaries; so it is not surprising that the flavour of baseball that first took root in the kingdom was the “Boston game”, which differed in a number of key respects from the “New York game” that went on to become the “national game”.[40] The “New York game” made its first appearance in the kingdom in 1866, introduced by Punahou graduate W.R. Castle. Our first rosters for baseball teams in the kingdom date from a year later, and a game played on the Punahou School diamond.

PIONEERS.—G. Roberts, p; A.W. Judd (captain), c; E. Macfarlane, 1st b; S. Nott, 2d b; F. Wunderberg, 3d b; J.H. Black, ss; Thos. Snow, rf; H.E. Whitney, lf; A.W. Carter, cf. PACIFICS.—C. T. Gulick, p; W.S. Wond (captain), c; G. Harbottle, 1st b; J. Nakookoo, 2d b; J.N. Gillman, 3d b; J. Naone, ss; G. Laanui, rf; J. Meek, lf; J.E. Bush, cf. H.G. Crabb and C.H. Rose, scorers.[41]

The Pacifics won the game 11–9. Scholars Frank Ardolino and Michael Johnson have done much to analyse this game, its players, and their connection to Punahou School.[42] We can, for example, following their lead, pick out players of Native Hawaiian and hapa haole (mixed European and Native Hawaiian heritage) heritage in the Pacific team, including Gideon La’anui (1840–1871), a member of the Hawaiian royal family and brother-in-law of Bruce Cartwright. Bruce was one of the two sons of Alexander Cartwright Jr who would take up the game while a pupil at Punahou. All the players in the August 1867 game were second-generation Hawaiians.[43]

My interest here is the contribution made by players of British heritage. We can cite, for example, two of the hapa haole players, William Saffery Wond, Jr (1841–1918), captain of the Pacifics, and John E. ‘Ned’ Bush (1842–1906)¸ both of whom had English fathers and Native Hawaiian mothers.[44] To explore this British connection further, it is useful to look at a parallel development, as 1867 was also the year that a cricket club was formed in Honolulu.

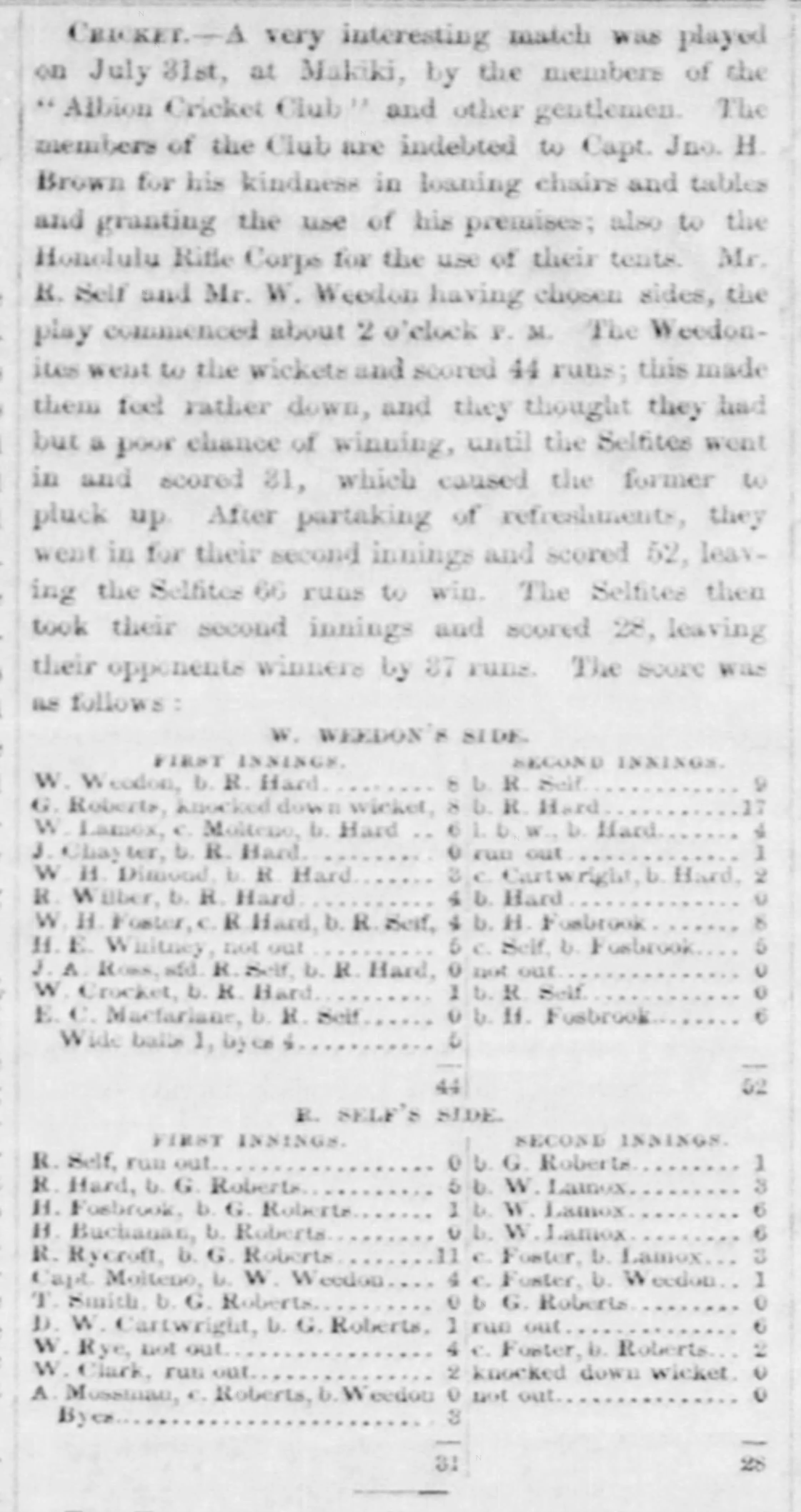

W. WEEDON’S SIDE.—W. Weedon (captain); G. Roberts; W. Lamox; J. Chayter; W.H. Dimond; R. Wilber; W.H. Foster; H.E. Whitney, J.A. Ross, W. Crocket, E.C. Macfarlane. E. SELF’S SIDE.—R. Self (captain); R. Hard; H. Fosbrook; H. Buchanan; R. Rycroft; Capt. Molteno; T. Smith; D.W. Cartwright; W. Rye; W. Clark; A. Mossman.[45]

The “Albion Cricket Club” played its first game at Makiki—the purported location of Cartwright’s first baseball diamond—on 31 July 1867, a few weeks before the Pioneers and Pacifics took to the field at Punahou. Before turning to the players who turned out for both the cricket and baseball teams, it is worth mentioning two of the players who turned out for the cricket team only: ‘Capt. Molteno’ was Frank Molteno (1816–1869), a former whaling ship captain of mixed Italian and British descent. Meanwhile, ‘D.W. Cartwright’ was almost certainly De Witt Cartwright (1843–1870), eldest son of Alexander Cartwright, Jr. De Witt was said to have helped his father lay out the baseball diamond at Makiki in 1852; in this light, finding him here at Makiki in 1867 playing cricket, not baseball, is interesting.[46]

Turning now to the players who turned out for both the cricket and baseball teams in the summer of 1867, we have three: E.C. Macfarlane, G. Roberts, and H.E. Whitney. Alas, ‘G. Roberts’ is too generic a name to permit a positive identification, which is a particular shame as he was the bowler for Weedon’s team in the cricket game and pitcher for the Pioneers in the baseball game. All that we can say with certainty is that his full name was George Roberts, and he continued playing cricket in the kingdom, including against a team from H.M.S. Tenedos in February 1874 while that ship was in Hawaiʻi for the coronation of King Kalākaua (Hawaiʻi’s third king in three years). This suggests a British heritage. However, at the same time, it has to be acknowledged that ‘H.E. Whitney’ was Henry Ely Whitney (1850–1883), a Punahou graduate of American heritage, the son of Henry Martyn Whitney, a prominent Hawaiian newspaperman and advocate for closer ties between the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and the USA. Simply being a cricketer is not an indication of English origin.[47]

We can be positive of the identification of “E.C. Macfarlane”. Significantly for our story, he was Edward Creamor Macfarlane (1848–1902), the son of British missionaries. Two of Macfarlane’s younger brothers, Clarence William Macfarlane (1858-1947) and Frederick Washington Macfarlane (1854–1929), would also, in time, take up baseball in the kingdom, the former playing for the Wideawake/Athlete Club alongside Lorrin Thurston, the man who would go on to play a leading role in the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom and later annexation of Hawaiʻi by the United States.[48]

Like many of the 1867 baseball and cricket players, Edward Macfarlane would go on to play a prominent role in the government of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and remain in politics after Hawaiʻi’s annexation. There would be a further connection between the Macfarlane family and politics when Edward’s sister, Helen Blanche Macfarlane (1853–1880), became the second wife of William Henry Cornwell Jr (1843–1903), an American-born sugar planter and politician.[49]

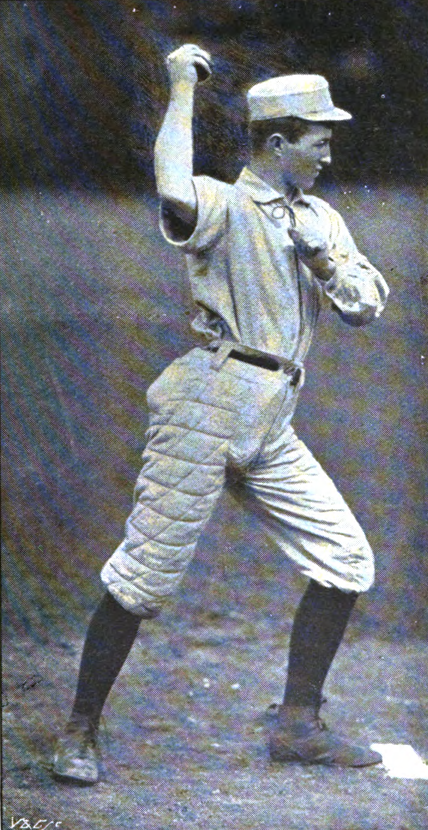

This marriage would lead to an unlikely sequel to the story of British involvement in early baseball in Hawaiʻi: Hawaiian involvement in early baseball in Britain. Helen and William’s eldest son, William Henry Cornwell III (1876–1954), was a superb athlete, and while attending King’s College London school in 1894, was recruited to play baseball for the top baseball team in London, the Thespians, pitching the team to victory in the 1894 English National Amateur Baseball Championship aged just 18.[50]

The Thespians, as the name suggests, were mostly entertainers, and almost all of North American origin. Their captain and co-founder, music hall star R.G. Knowles, in his 1896 book on baseball, although wrong about the place of Cornwell’s birth (he was born on Maui), had nothing but praise for his young star.

THE PITCHER DELIVERING A BALL. The illustration of the pitcher in the act of delivering the ball is a portrait of the finest pitcher who has yet appeared in England. He won the championship for the Thespians, 1894. W.H. Cornwell was born in San Francisco, and he was located in London for two years at King’s College, where he made a record in the sports, if nothing else. At Stamford Bridge Grounds, 1894, he won the high jump, the long jump, putting the shot, the 120 yard hurdles, and the 100 yards, which he won in 10 3-fifths seconds. He also won the special prize for winning the largest number of events.[51]

The Macfarlane genes put to work on a diamond in the old country.

THE SCOUT.—This ship, whose Captain and Officers have made many and fast friends at the islands, sailed away on Thursday last, homeward bound for “merrie England”. She gave us some guns as a farewell salute, and trailed from her masthead (in accordance with the ancient custom of a man-of-war when homeward bound) a long pennant,—we won’t undertake to say how many hundred feet in length?[52]

After a successful observation of the transit of Venus on 9 December 1874, the Scout, carrying the observation party, set sail for home a week later, arriving back in England on 13 May 1875; as if knowing their intended fate, her engines failed as she came abreast of the Isle of Wight, and she had to be towed into Sheerness, where her officers and crew were paid off and the ship retired. She would be broken up two years later.[53]

In a further strange and forlorn postscript to her cruise, Edward A. Ford, Lieutenant of Marines and one of the Scout nine, had failed to return from shore leave during the voyage home and been entered into the books as a deserter, his name removed from the Navy Lists. If this was not already a great enough blow to his family, it was later discovered that the reason he had not returned to the ship was that he had been murdered on shore. His name was restored posthumously to the Navy Lists, but this can have been of small comfort to his family.[54]

Richard Wellings was not on board the Scout when she returned. He had transferred to H.M.S. Tenedos before Scout left Hawaiʻi and spent a further three months in the Pacific. Admiral Cochrane, commander-in-chief of the Pacific Station, rated Wellings highly as a pilot and needed the Tenedos to go to San Jose de Guatemala to remonstrate with the Guatemalan government over the “Magee Affair”, the flogging by a Guatemalan army officer of a British vice consul. Guatemala paid an indemnity of $10,000 to make the affair and the Tenedos go away. Wellings finally reached England, having crossed the US from San Francisco to New York before taking passage with a steamer, in March 1875; ironically, given his extra months of service in the Pacific, arriving ahead of his former shipmates on the Scout.[55]

Wellings was promoted to full Lieutenant in 1877 and Commander in 1893, but only became a Captain on his retirement in 1900. He perhaps found his best role as an instructor on the training ship Active in the 1880s. He died in Hampshire in March 1913.

H.B.M.S. “SCOUT”. To the Editor of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser: SIR.—Will you kindly allow me a small space in your valuable paper, not so much to question the truth, as to throw light upon an article, entitled “Jack a Philosopher and Patriot”, seen the other day in one of the Honolulu papers[…]Does the anonymous correspondent imagine for one moment that “Jack”, whether a “Philosopher” or block head, cares one straw how the “Alabama Claims” were settled? Or if they were not settled even now, that that would alter the feelings existing between the two ships’ companies. Shall I tell you, Sir, the reason we have been so friendly?[56]

The years immediately following the end of the American Civil War were difficult ones for Anglo-American relations, exacerbated by conflicts of interest in regions like the Pacific. Yet, throughout this period, sailors of the two powers found common ground on the sports field. The reason the crews of the Scout and Benicia had been so friendly, according to the letter writer, was that the crew of the Benicia included British-born sailors, including old shipmates of members of the Scout’s crew. They had much in common. Meanwhile, Richard Wellings, enamoured of baseball, aspired to beat the Americans at their national game. The spread of baseball across the Pacific undoubtedly benefited from the presence of men with such spirit. However, it has also to be said that when Britons and Americans each proved superior at their own national game, honours were shared, and everyone went away happy. It can be argued then that Richard Wellings did his country a service by teaching his shipmates the rudiments of the game of baseball, and an even greater service by not quite achieving his dream. Such is great power politics.

Jamie Barras, February 2026.

Acknowledgements: This piece was inspired by conversations with Gabriel Fidler of the British Baseball Hall of Fame and Andrew Taylor of the Folkestone Baseball Chronicle Facebook page.

Back to Diamond Lives.

Notes

[1] All sources in endnotes below.

[2] ‘Scout’, The Broad Arrow, 1 November 1873. See also: ‘H.M.S. “Scout”’, Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle, 29 October 1873. The game was played on 27 August 1873.

[3] Cator: https://www.pdavis.nl/ShowBiog.php?id=1412, accessed 17 February 2026.

[4] https://www.pdavis.nl/ShowShip.php?id=129, accessed 17 February 2026.

[5] Pensacola: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/p/pensacola-i.html; Omaha: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/o/omaha-i.html, accessed 17 February 2026. Results of the games at Coquimbo: See Note 2 above. For other instances of cricketers and baseball players facing each other in their respective sports in this period, see, for example, https://www.dreamcricket.com/articles/history-of-american-cricket/history-of-american-cricket-part-iv--1860s-civil-war--after/, and https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/summer-1874-new-game-in-the-old-country-u-s-teams-tour-england/, accessed 17 February 2026.

[6] Origins of baseball in Chile: https://protoball.org/Chile, accessed 17 February 2026. The Scout versus Valparaiso Cricket Club: ‘Scout’, The Broad Arrow, 6 June 1874. Cricket was played in Chile as early as 1829: https://protoball.org/In_Valparaiso_in_1829, accessed 17 February 2026.

[7] See Note 2 above.

[8] ‘Notes of the Week’, Hawaiian Gazette, 22 January 1873; ‘H.B.M.’s S. Scout’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser, 12 September 1874. Clutterbuck: https://www.pdavis.nl/ShowBiog.php?id=343. Trower: https://www.geni.com/people/Cornwallis-Trower/6000000002115814302. Sandiford, Ledgard, and Hume: Service records, National Archives. Tottenham: ‘Suicide of a Naval Officer’, Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 21 November 1889. Fraser: "England and Wales, Census, 1881", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q274-XYPK), Entry for John A M Fraser, 1881.

[9] Details of Wellings’ birth and family: entry for Richard H. Wellings, Waterloo, Hampshire, district, 1881 England Census. Passes exam for entry to Royal Navy College: ‘Naval Cadets’, Naval & Military Gazette and Weekly Chronicle of the United Service, 17 December 1864. Master’s Assistant: ‘Naval Appointments’, London Evening Standard, 12 May 1866.

[10] ‘Naval Appointments’, Morning Post, 14 May 1869. Monarch: https://www.pdavis.nl/ShowShip.php?id=1784, accessed 17 February 2026.

[11] https://www.peabodygroup.org.uk/about-us/our-history/, accessed 17 February.

[12] ‘The British Iron-Clads’, Portland Press Herald, 9 February 1870.

[13] ‘The Peabody Ceremonies’, Portland Daily Press, 27 January 1870; ‘The Monarch’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 19 March 1870; ‘Paragraphs’, St Joseph Gazette (St Joseph, MI), 24 March 1870.

[14] ‘The Scout’, Victoria Daily Standard, 22 May 1872.

[15] https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=12301, accessed 17 February 2026. Dates for Richard Wellings’ service: service record, Richard Harriman Wellings, National Archives, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D7578205, accessed 17 February 2026. The Scout’s planned journey to the Pacific: ‘The Scout…’, Hampshire Advertiser, 25 March 1871.

[16] ‘Base Ball’, Victoria Daily Standard, 3 April 1872.

[17] ‘Cricket at Colwood’, Victoria Daily Standard, 11 September 1872.

[18] ‘Notes of the Week’, Hawaiian Gazette, 8 May 1872.

[19] Pig War: Jewell, James Robbins (2015). "Chapter 1: Thwarting Southern Schemes and British Bluster in the Pacific Northwest". In Arenson, Adam; Graybill, Andrew R. (eds.). Civil War Wests: Testing the Limits of the United States. Oakland, California: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520959576-002. The dispute over where the border between Canada and the USA should lie, east or west of the San Juan Islands, was resolved in the US’s favour in October 1871. The Scout evacuated the Royal Marine garrison from the Islands in November 1872 in advance of the territory being handed over to the USA: ‘The Last of San Juan’, Victoria Daily Standard (Victoria, BC), 23 November 1872.

[20] See Note 18 above and ‘Notes of the Week’, Hawaiian Gazette, 10 April 1872.

[21] ‘The Scout at the Sandwich Isles’, Victoria Daily Standard, 10 February 1873.

[22] History of Kingdom of Hawaii and US and UK relations taken from here: Ralph S. Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, Vol. 2, 1854–1874, twenty critical years (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009).

[23] Quote: Kuykendall, Note 22 above, page 240.

[24] Arrival and departure of the Scout: ‘Notes of the Week: Departure of the Scout’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 29 March 1873. Departure of Pennock: ‘Notes of the Week: The U.S.S. California’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 3 May 1873. A full account of Scout’s visit to Hawaiʻi was sent by one of her officers to the English newspapers: ‘Cruise of H.M.S. “Scout” to the Sandwich Islands’, Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle, 31 May 1873.

[25] ‘Great Storm at Valparaiso’, North Devon Journal Herald, 4 September 1873.

[26] Richard Kouyoumdjian Inglis, Chilean Navy and Royal Navy: Past, Present and Future, Naval Review, 2020, 108, 505–509.

[27] Steedman: Captain Albert Gleaves, U.S. Navy, An Officer of the Old Navy: Rear-Admiral Charles Steedman, U.S.N. (1811-1890), United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 1913, 39, no. 1. Annapolis, Maryland. pp. 197–210. Cator, captain of the Juno: ‘A Blockade Runner’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 25 May 1872; Juno trying to run the blockade to Charleston: ‘More Blockade Runners’, Western Daily Mercury, 3 July 1863; Juno captured: ‘Capture of Another English Blockade Runner’, Baltimore Sun, 26 September 1863. Cator and the rest of his crew were repatriated to England, as was usual with the crews of blockade runners. Blockade runners: Ephraim Douglass Adams, Great Britain and the American Civil War (London: Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd, 1925).

[28] See Note 2 above.

[29] See Note 2 above.

[30] This was in Leicester in 1876. Daniel C. Beaver, “Baseball, Modernity, and Science Discourse in British Popular Culture, 1871–1883.” The Historical Journal, 2022, 65, no. 5, 1310–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X21000704.

[31] ‘The Transit of Venus’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 24 August 1874.

[32] Arkan Simaan, "The Transit of Venus Across the Sun", Physics Education, 2004, 39 (3), 247–251.

[33] George Biddell Airy (ed.), Account of Observations of the Transit of Venus, 1874, December 8, made under the Authority of the British Government, and of the Reduction of the Observations (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1881), page 5.

[34] I take my information on the movements of the 1874 Hawaiʻi transit expedition from the digital archives held at the University of Cambridge: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/collections/tov/1, accessed 19 February 2026.

[35] ‘Base Ball and Cricket by the Sailors’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 10 October 1874.

[36] See Note 17, final reference. In the Hawaiian press: ‘England—the American Base Ball Players’, Hawaiian Gazette, 6 September 1874. There was a further account published in early November: ‘England—the American Base Ball Players’, Hawaiian Gazette, 4 November 1874. It is worth noting here that the Americans won at least some of their cricket matches, albeit because they were allowed to field as many as twenty-five players against English elevens. The tour was not considered a success.

[37] See Note 36 above.

[38] ‘Game of Ball’, Polynesian, 7 April 1860.

[39] Frank R. Ardolino, "Missionaries, Cartwright, and Spalding: The Development of Baseball in Nineteenth-Century Hawaii." NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, 2002, 10, no. 2, 27–45. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/nin.2002.0001. Michael F. Johnson, “Beyond the Baselines: Baseball in the Hawaiian Islands as a Transnational Sport, 1840–1945”, PhD Thesis, 2014, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

[40] Boston Game: John Thorn, ‘Early Baseball in Boston’, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/early-baseball-in-boston-d86107fb8560?gi=0d825261fd65, accessed 6 January 2026.

[41] Taken from the scorecard here: ‘A Match Game’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 31 August 1867. This game was later memorialised as the ‘First Match Game of Base Ball In Honolulu’, Hawaiian Star-Advertiser, 30 August 1902.

[42] See Note 39 above.

[43] Kapikauinamoku, 'The Story of Hawaiian Royalty: Prince Keoua's Eldest Son Remained On Maui', Honolulu Advertiser, 7 December 1955.

[44] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/93846115/william-saffery-wond, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104324336/john-edward-bush, accessed 19 February 2026.

[45] Taken from the scorecard here: ‘Cricket’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 3 August 1867.

[46] Molteno: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Molteno-7, accessed 19 February 2026; Cartwright: https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/alexander-cartwright/, accessed 19 February 2026. Although “De Witt” would usually be rendered “DeWitt”, without the space, we can point to “D.W. Cartwright” last being mentioned in Hawaiian newspapers in 1870, the year that DeWitt Cartwright died.

[47] “Geo Roberts” playing cricket against H.M.S. Tenedos: ‘Cricket’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 7 February 1874.

[48] Edward Macfarlane: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/126751393/edward-creanior-macfarlane. Clarence Macfarlane: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/126751439/clarence_william-macfarlane. Frederick Macfarlane: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/126751386/frederick_washington-macfarlane. Clarence Macfarlane, Lorrin Thurston, and the Wideawake/Athlete club: ‘Base Ball Flourishes’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 29 May 1875. Frederick Macfarlane playing baseball: ‘Base Ball’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 24 July 1876. Thurston and the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom: Ralph S. Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, Vol. 3, 1874–1893, Kalakaua Dynasty (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009).

[49] Helen Blanche Macfarlane Cornwell: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/126751363/helen_blanche-cornwell. William Henry Cornwell: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/45017110/william_henry-cornwell, accessed 19 February 2026.

[50] Cornwell III: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Cornwell-117, accessed 19 February 2026. Andrew Taylor of the Facebook Folkestone Baseball Chronicle has covered the career of W.H. Cornwell III in English baseball: https://www.facebook.com/FolkestoneBaseball/.

[51] R.G. Knowles and Richard Morton, ‘Baseball’, (London: George Routledge & Sons, 1896), 9–10.

[52] ‘The Scout’, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 19 December 1874.

[53] See Note 4 above, and: ‘Telegram from Our Portsmouth Correspondent’, Western Morning News, 15 May 1875. One of Scout’s last missions of its Pacific cruise was the building of a monument to Captain Cook on Hawaiʻi Island: ‘Monument to Captain Cook’, Shields Daily Gazette, 19 December 1874.

[54] The details of this strange incident are scant. ‘Late Naval and Local News’, Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle, 3 April 1875; ‘Naval and Military Intelligence’, The Times, 18 April 1876; ‘Naval and Military Intelligence’, Morning Post, 20 April 1876.

[55] The Magee Affair: ‘The Outrage at San Jose’, Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 26 May 1874. Tenedos dispatched: ‘De Omnibus Rebus’, Globe (Christchurch, NZ), 30 December 1874. Wellings’ service record and Cochrane’s praise: Note 15 above, second reference.

[56] Letter, Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 7 November 1874.

The 1882 Transit of Venus. US Naval Observatory. Public domain.

H.M.S. Scout. City of Vancouver Archives. https://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/h-m-s-scout. Public domain.

The Scout Nine at Coquimbo. Broad Arrow, 1 November 1873. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Coquimbo, Chile. Postcard, author's own collection.

Esquimalt, British Columbia. City of Vancouver Archives. https://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/esquimalt-harbour. Public domain.

Sailing vessels at wharf in Honolulu harbor, ca.1892-1907. Digital Public Library of America. Public Domain.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "Baseball in our insular possessions. Porto Rico -- Philippines -- Hawaii" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 20, 2026. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/704bd8c0-c5f6-012f-18e2-58d385a7bc34

The Pioneers and the Pacifics. Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 31 August 1867. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Cricket. Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HW), 3 August 1867. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain.

William H. Cornwell III, in England, 1894. Knowles and Morton, Baseball, George Routledge and Sons, 1896. Public domain.