Never Falter, Never Flag

Jamie Barras

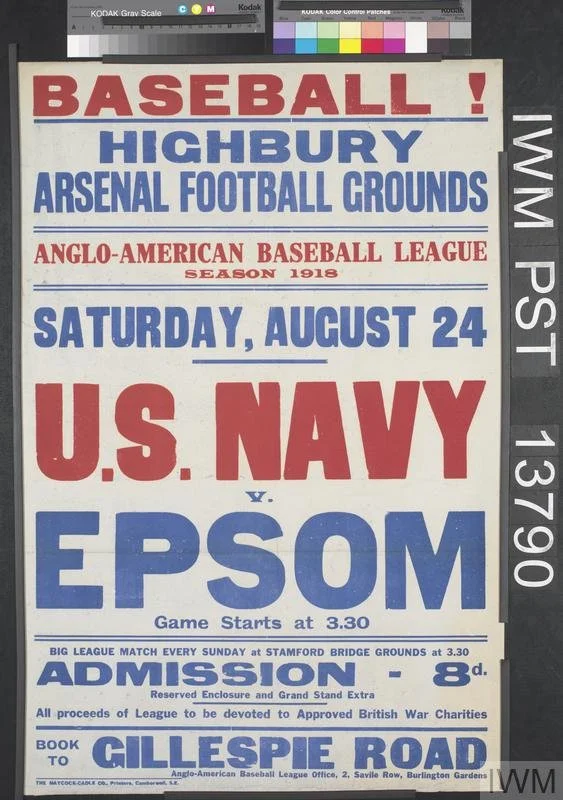

BASEBALL IN ENGLAND. Some time ago, the announcement was made that with the arrival of the Americans in England, an organised attempt was about to be made to capture this country for baseball, and in accordance with this scheme, the Anglo-American Baseball League will begin its campaign in earnest next Saturday, when four games will be played in the London district. Eight teams compose the League. Four of these are American—Army, Navy, Nortbolt, and Hounslow; and four Canadian—Epsom, Pay Records, Sunningdale, and Taplow.[1]

Authors Andrew Taylor, Stephen Dame, and most especially, Jim Leeke have written extensively about the 1918–1919 Anglo-American Baseball League (AABL) and the wartime military leagues that preceded it.[2] I cannot improve on those accounts, and it is not my intention to try. Instead, what I want to do here is take a step back and look at the AABL, not as it was, a continuation of the informal military baseball leagues that had been established by English enthusiasts and units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CAF) and American Expeditionary Force (AEF), but as its originators had intended it to be: a league designed to exploit the presence of millions of CAF and AEF personnel in the European theatre in the summer of 1918 to bootstrap a postwar international circuit that would include both imported North American players and local players, with games played not only in England but right across Europe, initially in army encampments and recreation centres, yes, but ultimately, in regular sporting venues.[3]

More specifically, I want to look at how the league intended to make use of two Americans with extensive experience in providing entertainment to the troops and doing business in Europe to achieve its goals. Running through this, as we will discover, there is a connecting thread in the somewhat unlikely form of the late-Victorian/Early-Edwardian roller skating craze.

BASEBALL PLAYERS TO JOIN UP. (FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT) NEW YORK, July 20. Mr. Baker, Secretary of War, has decided that baseball players are subject to be drafted into the Army and, as a consequence, it looks as though London and Paris, for the period of the war, will replace this country as baseball centres of the world.[4]

The first thing to understand about the Anglo-American Baseball League is the context surrounding its formation: it was conceived in January 1918 at a time when there was every reason to believe that the war would continue for years. The U.S. Army was in the process of a massive recruitment campaign, as part of which, there was a very real chance that so many professional baseball players would be called up that the centre of gravity of America’s national pastime would shift to Europe for the duration.

It was against this backdrop that an American oilman based in London, Wilson Cross, conceived the AABL. Cross persuaded 30 other American businessmen based in London to put up $30,000 to back the league under the auspices of the London Baseball Association Company Ltd. Included in their number were two men involved in previous attempts to popularise American baseball in England, both of whom had also been involved in the ad hoc military leagues: player Dr Robert N. Le Cron and administrator Newton Crane.[5]

Crane, an American newspaperman and lawyer who had settled in England, had a long history at the top of the American game in the country, dating back to 1889, something I have covered elsewhere.[6] Le Cron, a name also rendered as Le Crow, Le Cran, Lecron, etc., was a physiotherapist who had been playing baseball in Britain since his arrival in the country in 1908, initially in the 1906–1912 London leagues under the British Baseball Association (BBA), and latterly as a member of the London Americans team founded and run by the organiser of one of the wartime military leagues, fellow former BBA player and administrator, John Gibson Lee.[7]

It is worth noting here that in the spring of 1914, before the outbreak of the First World War, Crane, Le Cron, and Lee were all involved in a successor to the BBA also called, in at least one newspaper, the ‘London Baseball Association’, which it was hoped would revive baseball in London; an attempt brought to an end by the outbreak of war. It is not clear what, if any, connection, beyond the name, this London Baseball Association had with the London Baseball Association Company created by Wilson Cross and incorporated in 1918. There had also been an entirely unconnected London Baseball Association back in the 1890s—albeit one backed by Newton Crane in the early period of his involvement in American baseball in Britain. Lee was, at one stage, involved in the planning of the Anglo-American Baseball League, and he may have expected that his London Americans team, of which Le Cron was a member, would join the league. Events worked out differently, and Lee would himself die, aged just 32, in what is known to history as the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918.[8]

Wilson Cross was not alone in seeing an opportunity in the presence in Europe of large numbers of American baseball players and fans: ‘Uncle Sam Leagues’ sprang up across the European theatre, attracting the interest of baseball entrepreneurs in America, some of whom, like former Chicago Cubs player and current representative of the Knights of Columbus fraternal order, Johnny Evers, made the trip to Europe, On assuming the role of, in the words of one journalist, the ‘generalissimo of baseball in France’, Evers told all and sundry that he was going to hold a ‘World Series in Berlin’, and what was happening in Europe would result in a ‘baseball revolution’ back home. It is also worth at least mentioning that, back in 1912, boxing promoter Richard Klegin claimed—the emphasis is on the word ‘claimed’—to have set up the ‘International Baseball League Of Europe’ with teams in ‘Liverpool, London, Berlin, St Petersburg, and Paris’. This was pure flim-flam—Klegin was a famously less-than-reliable character even by the standards of boxing promoters.[9]

What separated Cross’s efforts from those of the likes of Evers was that Cross intended to make use of players imported from the US to form teams that would play in military camps—against each other and against military teams—to bootstrap the creation of a post-war civilian overseas circuit. It has to be said that when this was announced in February 1918, it was greeted with some—ultimately, justified—scepticism back in the States, not least because the idea was that these teams would be formed of men unfit for or exempt from military service, so unlikely to include professional ball players from the major leagues. At least one US commentator opined that troops would have little interest in watching teams they had never seen before and would favour games between army and navy teams instead. Indeed.[10]

Undaunted by such criticisms, Cross placed the task of making the league happen in the hands of two Americans, one of whom had experience managing minor league teams and had done business in Europe, while the other had made Europe his second home and had all the necessary contacts among both military and civilian authorities in England to bring the project off: AABL executive board member William A. ‘Billy’ Parsons and AABL managing director Howard E. Booker. Both men had been doing business in Europe for a number of years, latterly working together to provide entertainment at army camps in the European theatre. And both had first travelled to the continent to exploit the spread from America to Europe of the roller skating craze.

THE ROLLER SKATING CRAZE. Some idea of how the roller-skating “boom” has taken hold of all classes of society is afforded by the fact that there are in the country more than 300 skating-rink companies, employing 10,000 instructors, besides a larger number of bandsmen and various attendants.[11]

I have written about the rise and fall of the rolling skating craze in Edwardian Britain elsewhere.[12] What is of interest to us here is that the craze spread to Britain from America, where the interest in roller skating had been through a series of booms and busts ever since the patent for the first practical quad skate expired in the 1880s, bringing down the cost of skates and making the pastime affordable for all. Roller skating was arguably, after dancing, the most popular mass-participation pastime of the last two decades of the nineteenth century in America. The craze also gave rise to several sports: what we would now call figure skating, but was known at the time as ‘fancy skating’, speed skating, and roller polo.

The latter is particularly important to our story. It would become known in Britain as ‘roller hockey’, and the best way to picture it is as ice hockey on roller skates played between teams of five or seven players. As roller skating was a winter pastime, roller polo was a winter sport, and, as America famously never embraced what most of the world calls ‘soccer’ (Association Football), roller polo was probably the most popular winter sport in America until the rise of first basketball and then [American] football. Critically for us, much as, in later decades, baseball players would play football in the winter to stay in shape for the summer baseball season, in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, baseball players would play roller polo in the winter months.

One such player was Walter Arlington ‘Arlie’ Latham (1860–1952), who, in later years, would go on to become the face and ‘official umpire’ of the Anglo-American Baseball League. Latham devoted over 70 years of his life to baseball and spent a good number of his early years in the game playing baseball in the summer and roller polo in the winter. He was, however, a complicated character, and, although he was recognised as a great base runner, he owed his considerable fame to his reputation as ‘a comedian of the diamond’ for his barracking of the opposition to put them off their game and his endless supply of baseball-related anecdotes. By the time Latham arrived in London in 1917, he was down and his luck and working as a shoe salesman; it is hard to know if his subsequent recruitment by the AABL helped or hindered its backers’ cause, not least given the mirth that the news of his involvement generated in the American press (‘no wonder Englishmen think baseball a funny game’). It is worth taking a moment to address the reports in English newspapers in March 1918 that the AABL was Latham’s creation. Given the wealth of evidence to the contrary, it is fair to regard these reports as simply a smart bit of promotion by Wilson Cross and/or Howard Booker—which is not to say that Latham’s presence in London may not have sparked the idea of bringing professional ballplayers to England.[13]

To return to the connection between baseball and roller polo: it extended to the managers of owners of baseball clubs also managing and owning roller polo clubs, and using the roster of the former to fill the roster of the latter. One such ‘two-fer’ owner–manager was Billy Parsons.

NEW ENGLAND BASEBALL. At a meeting of the New England Baseball league circuit committee, held at the Essex House, Lawrence, Saturday afternoon, applications for franchises were submitted by Lawrence and Fall River. Action was not taken. Thomas Burns of Springfield and W.A. Parsons of roller polo fame are seeking the franchise in Lawrence.[14]

William Adna ‘Billy Parsons (1867–1925) was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, in May 1867, and by the age of 16 was playing roller polo for the New Britain, Connecticut, team in the National Polo Association League. In the course of a 20-year playing career, during which he saw roller polo go in and out of fashion at least twice, he took five different teams to the championship, culminating in a second win with a second New Britain team, for which he was player–manager–owner. He also found time to qualify and work as a civil engineer.[15]

By 1899, recognising that the money in roller skating lay somewhere other than in roller polo, Parsons had started investing in roller rinks, first in Connecticut and Massachusetts, then, later, in New York, which became his home; his most significant investment would be in the Steeplechase Park rink at Coney Island, an association that would, in later years, lead to the claim that he ‘…owns about all of Coney Island’.[16] Significantly, for our story, Parsons’ involvement in rink ownership and management gained him experience in booking entertainment, as rinks used live bands to provide the musical accompaniment to public skating sessions and performances by specialty skating acts.[17]

Just as important for our story, by 1901, Parsons had also moved into baseball team ownership and management with the Portland and Lawrence franchises in the New England circuit.[18] Never one to sit still, in 1909, Parsons extended his business interests to Europe, travelling there in the guise of an agent for a roller skate manufacturer. He engaged in promotions in Germany and Italy,[19] and his business also took him to England, then in the middle of its roller skating boom. It was there that he met another expatriate American roller skater who had been working as the manager for a roller rink in London since 1908. His name was Howard E. Booker.[20]

WEDDING CEREMONY HELD UP. Allegation Against the Bridegroom. All's Well. The crowd of people who waited outside St Martin's Registry Office, London, for a glimpse of Miss Ivy Featherstone, the bride for whom two suitors played “odd man out,” were given an unexpected thrill. Mr Howard Elliott Booker, the bridegroom, came out and hastened up the street. He was followed by the bride's brother, Mr Horace Featherstone, a London police constable. An hour later, Mr Booker and Mr Featherstone drove up in a motor car. When Mr Booker again emerged, his bride was on his arm. A short time before the ceremony, Mr Featherstone went to the register office and announced that he had an objection to the marriage. He said he had received a telegram to the effect that the prospective bridegroom already had a wife […]The bridegroom indignantly denied it. Mr Booker, an American citizen, said he could prove his contention at the American Consulate [which he did by obtaining the paperwork that showed] that the woman mentioned in the telegram was the wife of an American army officer.[21]

Howard Elliot Booker (1887–1976) was a magnet for trouble. He ran out on his first wife, claimed to have married a second, and then had to hastily disavow that marriage when he came to marry his third/second. A professional roller skater in his youth, he moved to England in 1908 to take advantage of the spread of the roller skating craze to this country and then had to scramble to find another line of work once that bubble burst. He dabbled in boxing promotion, horse breeding, and cinema management before finding a niche organising entertainment at military camps in the First World War.[22]

Moran Should Be Interested. There is a proposal to match the winner of Thursday's contest with Frank Moran, and Messrs H. E. Booker and [Jem] Barry, who have been concerned with promotions at Larkhill Cinema, Salisbury, and other military districts in the West country, are prepared to offer a purse for such a contest to take place at Bulford. By the way, the soldiers of the Plain will this week have an opportunity of seeing the Johnson and Willard film, which will be shown at the Military Cinema at Larkhill.[23]

Booker’s value to the Cross and the AABL was his experience in providing entertainment at military camps and the contacts with the military and civilian authorities that this gave him. In 1915, he had taken over the concession for providing entertainment to British and Canadian troops at the garrison town of Larkhill, Salisbury Plain, and opened the 2000-seat Military Cinema, which he also used as a venue for boxing matches. Once America entered the war, he extended his activities to include providing entertainment to US troops, too.[24]

A key contact for the latter was a USNVR officer stationed in London that Booker knew from back home in California, Tracey Bennett Kittredge. Kittredge had been a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford when the war broke out and went on to become a leading figure in the American-organised Belgian Relief Mission, something that allowed him to travel between London, Paris, and Berlin and mix freely with officials from all three governments. This led to him making the acquaintance of several British military intelligence officers, and following the US’s entry into the war, Kittredge became an intelligence officer himself. He was also assigned the job of looking for ways to keep up the morale of American soldiers. Enter his old friend Howard E. Booker and his entertainment shows for the troops. Booker’s friendship with Kittredge would lead to the AABL gaining the active support of Admiral Sims, commanding officer of American forces in the European theatre.[25]

Meanwhile, the man who was working stateside to help Booker arrange entertainment for the troops was Billy Parsons, who had contacts in the entertainment world through his role as a manager and owner of roller rinks. Although this may have been a renewed acquaintance, it seems more likely that the two had been in business together since their first meeting in London in 1909 or 1910, as it was later said that Booker was Parsons’ ‘former London manager’, which suggests that Parsosn had hired Booker as the UK representative for the roller skate manufacturer for whom Parsons had been acting on his 1909–1910 European business trip.[26]

It will be remembered that, as originally conceived, with no knowledge of how long the war would last, the AABL’s plan was to begin by staging games between teams formed of players it would import from the States and Canada at military camps in England and France. The expectation was that military teams would also be part of this first iteration of the circuit, given how many professional baseball players it was anticipated would be in the armed forces by the summer of 1918. The expectation was that Booker would find those venues, and indeed, when the plan for the league was announced in February 1918, Booker was confidently predicting that there would be games in the camps in London, Paris, and Brighton, as well as in the US Army’s Aix-les-Bains and Vichy recreation centres.[27]

Parsons’s role in the AABL’s plans—almost certainly secured for him by Booker, given both their existing business relationship and the fact that Booker was the man on the spot in London when the AABL was conceived, while Parsons was in New York—was to serve as the recruiter for the civilian baseball players who would make up the teams that would tour the camps alongside the military teams. The recruitment goals were initially modest, with, by February 1918, Parsons being ‘ready to sign’ the 30 players that the league felt it needed to form the nucleus of teams that would also include serving soldiers already in the European theatre and ‘other athletes who had taken up the game (in the context, probably a reference to the players like Bob Le Cron who had been playing the game in England for years). However, it was anticipated that these needs would increase once the league was established.

Alas, it was not to be.

The Anglo-American Baseball League, which was launched here last February, is almost ready to open its season. However, there has been a revision of the original plan, and the league idea, as it exists in this country, will not be carried out. Some of the military camp authorities in England refuse to permit their teams to travel. They do not object to league contests on their home fields. In consequence, the men behind the league are organizing two clubs here, which will play all their games on the road, and thirty men are to be sent to England in batches of ten.[28]

In the event, even those 30 men did not make the trip, and, as can be seen from the quote that opened this piece, the AABL on launch day was formed entirely of Canadian and American military teams from units in the London area, most of whom had non-combat roles (clerks, hospital staff, lumberjacks). Readers are recommended to seek out the works of Taylor, Dame, and Leeke for the full story of the two seasons of baseball in the AABL.[29]

Booker and Parsons continued to boost the AABL regardless; at the close of the first season, Booker wrote a letter to US newspapers trumpeting the achievements of the first season, the highlight of which was undoubtedly the 4th of July game in front of King George V, which had an attendance in the tens of thousands.[30] There is even evidence that the backers of the AABL were contemplating adding a winter [American] football league to their calendar: we have letters and telegrams dated November 1918 that show that Howard E. Booker was in conversation with the Spalding Sporting Goods Company to ship football equipment to London.[31]

Then the war ended, and all that most Americans and Canadians in Europe could think about was getting home.

Not all American servicemen returned to North America as soon as the war was over (or as soon as the American and Canadian governments could arrange transport), however. Over 1000 American servicemen took advantage of the US Government’s offer to pay for soldiers and sailors to complete a period of study at British universities. This was to lead to a short-lived inter-varsity league that ran for a single season in 1919, under the auspices of the London Baseball Association, formed of teams of American servicemen studying at Oxford, Cambridge, King’s College London, Birmingham, Manchester, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen.[32]

More significantly, for our story, the continuing presence of American Army officers in the London area was to provide Howard E. Booker with his next money-making scheme, removing any need for him to continue to try to make a success of the AABL.

AMERICAN'S DANCES. BUT NO LICENCE. A POINT OF LAW. William Francis Mitchell, Kensington High Street, and Howard Elliott Booker, Dover Street, W., were summoned at Marlborough Street for allowing, as occupiers of the premises, 31, Tottenham Court Road, to be used for public dancing without a license from the London County Council. It was admitted on all hands that the dances were conducted with the utmost decorum. Evidence given showed that tickets were sold at £1 each, and that the defendants were American citizens who were following out a well-known New York plan of providing amusement for officers and their friends by means of dances given by different hostesses.[33]

Following the Armistice, Booker went into business with a peddler of correspondence courses in ‘mental suggestion, magnetic healing, and telepathy’, by the name of William ‘Frank’ Mitchell. They started their partnership by offering taxi dancing by subscription—tickets were sold through agencies to American Army officers stationed in the London area for events at a private club that offered an opportunity to take to the dance floor with hostesses provided for that purpose. Mitchell and Booker went this route to avoid having to pay for a licence for public dancing. However, London County Council saw through the ruse and fined the pair £50 each—a pretty penny in 1919.[34]

Booker’s partner Mitchell was already very familiar with the courts, and they with him—just one year earlier, he had been fined £100 for sending circulars through the post in defiance of wartime controls on the use of paper; two years before that, his boss (and brother-in-law), Prather, had been deported as an undesirable alien in connection with the same activity.[35]

Undeterred by their first brush with the law as dance hall proprietors, and leveraging Booker’s familiarity with the roller skating business, Mitchell and Booker went on to open a string of dance halls in the early 1920s, many of them in former roller skating rinks, prime among them the venue that would become famous in later years as the Hammersmith Palais. They would also open at least two nightclubs. Both of these businesses would, for the next few years, keep the courts busy over breaches of the Sunday trading laws and failure to obtain liquor licences.[36]

In November 1921, Mitchell and Booker opened their first dance hall in Paris, the Apollo Theater, and Booker announced himself as the man who had brought American jazz to Paris. In fact, African American jazz musicians had been active in Paris since the Armistice, and by 1921, Montmartre was already home to a host of African American-owned jazz clubs. There is also mounting evidence that Booker was involved in the International Baseball League, a 1922 attempt to bring American baseball back to London that was centred on several old AABL players who, by 1922, were working for the Mitchell—Booker entertainment empire in one capacity or another.[37]

In short, after the failure of the AABL, it was business as usual for Howard Elliot Booker.

The presence of American Army officers in the London area was to have a second impact on Booker’s life. One of the officers who had taken advantage of the US Government’s offer to fund his studies was a young anti-aircraft artillery officer, and future Major General, by the name of Aaron Bradshaw Jr. Bradshaw began a course of study at Oxford in mid-1919. We do not know if he played baseball while he was there, but we do know that Oxford was where he met his future wife. They were married shortly afterwards.[38]

Aaron Bradshaw Jr was the ‘American Army officer’ married to the woman that the 1923 telegram claimed was Howard E. Booker’s wife.

In addition to the notice given by Mr Booker, who described himself as a company director and bachelor […], Mr E. L. Robertson, an American dental surgeon, living at the Piccadilly Hotel, had also given notice of his intention to marry this much-sought bride. Mr. Robertson did not put in an appearance at the register office on Saturday. It is understood that at one time he was engaged to Miss Featherstone.[39]

The whole business surrounding Booker’s marriage to his second wife in January 1923 was a strange one. At the time that Booker and his future wife, chorus girl Ivy Featherstone, met, Ivy was engaged to an American dental surgeon living in London by the name of E.L. Robertson. Sometime after this first meeting, Ivy broke off the engagement with the intention of marrying Booker, and the pair applied for a marriage licence. Two days later, Robertson also applied for a licence to marry Ivy—without her knowledge or approval, Ivy would later insist. Then, on the day of the wedding itself, someone—Robertson?—sent Ivy’s policeman brother a telegram to say that Booker was already married to a woman named Edith Doulton. This triggered a madcap dash by Booker and Ivy’s brother to the American Consulate so that Booker could prove that Edith Doulton was, in fact, married to US Army officer Aaron Bradshaw Jr.[40]

What did not make the newspapers was the fact that, from 1909 up until at least November 1918, Booker and Edith Doulton had been living together as man and wife. Edith Doulton, full name Edith Gwendoline Doulton (1894–1980), was born and raised in London, the daughter of an English father and a Spanish mother. She and Booker met in 1909, not long after Booker arrived in London to work as the manager of a roller skating rink, and we can assume, became a couple not long after.[41]

In 1909, Booker was still married to his first wife, Ivy Florence Bauer, whom he had married when he was 20 and she was 18; however, the marriage effectively ended a year after it began when Booker left the US for England in 1908. Ivy Bauer would obtain a divorce on the grounds of desertion in 1910.[42] Although in 1916 and 1917, Gwendoline Booker—using that name—would obtain US passports on the grounds that she was American by marriage to Booker, there appears not to have ever been an actual marriage (at least, no record of one in England). To support this, we can point to Booker still describing Gwendoline as his wife in November 1918, but Gwendoline/Edith, who gave her name as ‘Edith Doulton’, not ‘Edith Booker’, registering her marriage to Aaron Bradshaw Jr no more than 9 months later (a very short time to obtain a divorce in the days before no-fault divorces).

It was, in all, a strange affair. As soon as the January 1923 ceremony was over, Booker and his new bride left for a honeymoon in Monte Carlo. A daughter, Barbara Mary, would be born just nine months later, and the family would spend the next ten years travelling the world as Booker continued to chase after one business deal after another.[43]

The only mishaps of the show occurred when the male roller skater dropped his partner, and when four girls of the chorus line got lost. The girls-lost incident occurred some time between the first and second show, after the girls went out for a short walk. Howard E. Booker, producer and director of the revue, a sergeant and soldier made a quick search of the theater and reported them missing. It was some ten minutes after the show was supposed to begin that they turned up.[44]

By the time of America’s entry into the Second World War, Booker was back in the US and describing himself as the head of the ‘All American Entertainment Inc.’, a provider of entertainment to US Army bases. At least one of his shows featured roller skating. Postwar, he went into business operating amusement concessions at race tracks in New York state and floated a bill to allow off-track betting in the state, which failed to pass. He died in California in 1976. His second wife, Ivy, had died ten years earlier, but he was survived by his daughter Barbara Mary. He did not rate an obituary in the newspapers.[45]

Billy Parsons had died way back in 1925. After the failure of the AABL, he had returned to managing his roller rinks businesses. For the first few years after the war, he continued to supply Booker with American entertainers, in this case, for Booker and Mitchell’s Palais de Danse. Parsons’ passing was marked by the newspapers, but there was no mention of his connection to the Anglo-American Baseball League; instead, his death was recorded as the passing of ‘an old-time roller polo star’.[46]

ANGLO-AMERICAN BASEBALL LEAGUE. SUNDAY, May 25th, EPSOM v. U.S. NAVY. Game starts 3.30 p.m. STAMFORD BRIDGE GROUNDS, WALHAM GREEN.[47]

Booker and Parsons had gone into the business of promoting the Anglo-American Baseball League believing that they would be able to sell Europe on baseball the same way they had sold it on roller skating; however, the league was a flawed idea that was, in any case, doomed by the unexpectedly rapid end of the war. There would, however, be more attempts to launch American baseball in Britain in the decades to come, and Howard Booker may have been involved in at least one of them. Britain’s baseball boosters were imperturbable.

Strike one, the pitcher throws the ball/And the man at the bat just misses it/Then the pitcher throws again/Into left field the batter whizzes it/First Base, second base/Never falter, never flag/ Ev’ry man and ev’ry child/Ev’rybody’s going wild/Other games you'll feel are mild/Come and do the baseball rag.[48]

Jamie Barras, October 2025

Back to Diamond Lives

Notes

[1] ‘Baseball in England’, Lancashire Evening Post, 11 May 1918.

[2] Andrew Taylor: https://www.facebook.com/FolkestoneBaseball#, accessed 3 October 2025. Stephen Dame: Stephen Dame, Coloured Diamonds: Integrated Baseball in the Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1918. Journal of Canadian Baseball, 2022, 1. 10.22329/jcb.v1i1.7696. Jim Leeke: Jim Leeke, Chapter 3: the Anglo-American Baseball League and Chapter Four: Opening Day, ‘Nine Innings for the King’, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co, 2015).

[3] The original idea behind the AABL including postwar plans was laid out in the first announcement of the league in February 1918; see, for example: ‘Will Start Ball League Overseas’, Fall River Daily Evening News (Fall River, MA), 20 February 1918.

[4] ‘Baseball Players to Join Up’, Evening Mail (London), 22 July 1918.

[5] Wilson Cross’s roll in founding the AABL and a list of its backers is given in: ‘Baseball Follows the Flag to the European Theater’, San Francisco Chronicle, 13 October 1918.

[6] https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-intolerance, accessed 4 October 2025.

[7] Andrew Taylor has written extensively on Robert ‘Bob’ Le Cron; see Note 5, above, first reference. For the BBA and John Gibson Lee, see: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-health-friendship-and-baseball-part-i, accessed 4 October 2025.

[8] 1914 LBA: ‘Anglo American Exposition: Independence Day’, Morning Advertiser, 6 July 1914; ‘Baseball at the Stadium’, Sporting Life, 25 July 1914; ‘Baseball for Britain’, Sunderland Daily Echo, 28 July 1914. 1890s LBA: ‘London Baseball Association’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 23 February 1894. Lee’s London Americans join forces with the AABL: ‘News Items’, Nottingham Evening Post, 15 April 1918. Lee’s early death: ‘Deaths’, Middlesex County Times, 23 November 1918.

[9] David Kohnen with Sarah Goldberger, ‘“Remain Cheerful” Baseball, Britannia, and American Independence, 4 July 1918’, 2023, Naval War College Foundation, downloaded from: https://nwcfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Remain-Cheerful-v3-1.pdf, accessed 22 January 2025; ‘World Series in Berlin’, Commercial Appeal (Memphis, TN), 16 June 1918; ‘Evers Predicts a Baseball Revolution’, Los Angeles Times-Record, 26 September 1918. Klegin: ‘Game Booking in Europe’, Washington Herald, 20 June 1914. https://thenextbaseballcountrywillbefrance.blogspot.com/2013/07/la-ligue-europeenne-de-baseball-acte-i.html, accessed 6 October 2025.

[10] ‘May Form League to Play Abroad’, Times (Trenton, NJ), 24 February 1918.

[11] ‘The Roller Skating Craze’, Arbroath Herald, 25 February 1910.

[12] https://www.ishilearn.com/the-spectacle-all-the-worlds-on-wheels, accessed 4 October 2025.

[13] Jim Leeke covers Arlie Latham’s life, career, and involvement in the AABL: See Note 2 above, third reference, chapter ‘Arlie Latham’. ‘No wonder Englishmen…’, see, for example: ‘Sport Chatter’, Bristol Daily Courier (Bristol, PE), 3 May 1918. For a summary of Latham’s roller polo career, see: Dan Parker ‘Broadway Bugle’, Courier-Post (Camden, NJ), 3 December 1952. For the AABL as Latham’s idea, see: ‘Baseball In England’, Hull Daily Mail, 20 March 1918.

[14] ‘New England Baseball’, Evening Herald (Fall River, MA), 2 December 1901.

[15] Spalding’s Official Roller Polo Guide (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1898), 33.

[16] ‘World of Sports’, Waterbury Democrat (Waterbury, CT), 1 November 1899; ‘Wants Polo for New York’, Waterbury Democrat (Waterbury, CT), 29 November 1907; ‘New Roller Rink at Steeplechase Park’, Times Union (Brooklyn, NY), 11 May 1907. ‘Owns about all…’: see Note 4 above, first reference.

[17] These bookings did always go to plan: ‘Verdict Won for Parsons’, Portland Sunday Telegram (Portland, ME), 15 October 1916.

[18] See Note 3 above.

[19] ‘Emperor William Will See Famous Trotter’, Oakland Tribune, 16 May 1909. Parsons lists his occupation on his 1909 passport application as ‘salesman’ and on his 1910 US Federal Census return as ‘commercial traveller, roller skating’: William A. Parsons, passport application, 21 May 1909, U.S., Passport Applications, 1792–1925, William A Parsons, Hartford, Connecticut, 1910 US Federal Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025.

[20] It is worth pointing out here that, although living in England, Booker travelled all over Europe promoting roller skating, so it is possible that Booker and Parsons met somewhere other than England. See Howard E. Booker, 1918 passport application, U.S., Passport Applications, 1792–1925, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025.

[21] ‘Wedding Ceremony Held Up’, Dundee Evening Telegraph, 8 January 1923.

[22] This information can be garnered from passport applications made by Howard E. Booker in 1915, 1916, and 1920, U.S., Passport Applications, 1792–1925; entry for Howard Elliot Booker, 1911 England Census, St Giles Without Cripplegate district; entry for Howard E. Booker, passenger lists, Saxonia, arrived Liverpool, 6 September 1916, UK & Ireland Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025; and ‘Playing Ball in Old England’, Tulare Advance Register (Tulare, CA), 15 June 1918.

[23] ‘News and Gossip of the Ring’, Sporting Life, 22 June 1915. The Johnson and Willard film’, as might be supposed from the context, is a reference to a film of the Jack Johnson–Jess Willard fight, Havana, Cuba, 5 April 1915: ‘The Willard–Johnson Pictures’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 12 June 1915. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IFZVlsLs9Eo, accessed 5 October 2025.

[24] For Larkhill concession, see Notes 3 and 24 above, and: ‘News and Gossip of the Ring’, Sporting Life, 9 April 1915. For film shows for British, Canadian, and American troops, see: ‘Live Tips and Topics’, Boston Globe, 18 October 1918.

[25] See Note 9 above, first reference.

[26] The evidence for Billy Parsons’ role in securing entertainers for Booker comes in the form of correspondence included in Parsons’ passport applications of 1918 and 1919: U.S., Passport Applications, 1792–1925, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025. In his 1918 passport application, Parsons includes a letter in which he states that his business in England is connected with ‘handling concessions for the British government furnishing entertainment for [word obscured] troops in army encampments’. In the 1919 application, is included a letter from Booker to Parsons asking him to secure the service of ‘the Black and White boys band’ for his new dance hall business with Frank Mitchell. ‘Former London manager’: see Note 5 above.

[27] See Note 3 above.

[28] Daniel, ‘High Lights and Shadows in All Spheres of Sport’, New York Herald, 9 April 1918.

[29] See Note 2 above.

[30] See Note 5 above, and Leeke, Note 2 above, final reference. It is worth noting here that the pandemic that would be known to history as the Spanish Flu Epidemic had already begun and it was of questionable wisdom to have mounted an event on that scale at that time–not that the public had been told any of this.

[31] This correspondence forms part of Billy Parsons’ 1918 US passport application; see Note 26 above.

[32] ‘University Baseball’, Liverpool Evening Express, 13 May 1919.

[33] ‘American’s Dances’, Marylebone Mercury, 21 June 1919.

[34] Mitchell and Booker and mail fraud: Truth, 4 June 1919. Mitchell had inherited the English end of the business from his former boss, Elmer Knowles/Prather, a mail fraudster on a grand scale: https://ehbritten.blogspot.com/2016/06/the-mail-order-occult-ring-saga-episode.html?q=prather, accessed 3 October 2025. Mitchell and Booker fined for not having a public dancing licence: ‘American’s Dances, Marylebone Mercury, 21 June 1919.

[35] Mitchell fined in 1918, Prather deported in 1916: ‘Paper Controller Defied’, Daily News (London), 2 August 1918.

[36] Mitchell and Booker’s Palais de Danse: https://www.jazzageclub.com/dancing-world-magazine/5288/, accessed 3 October 2025.

[37] ‘American Jazz Taken to France by Frisco Man’, Independent-Leader (Sacramento, CA), 18 December 1921. For the story of African American jazz in Paris, see: William A. Shack, Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001). Booker and the International Baseball League of 1922: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-art, accessed 30 October 2025.

[38] Aaron Bradshaw Jr’s Army career: ‘Logistic Chief Leaves Army’, Morning Union (Springfield, MA), 1 February 1953; meeting his wife while at Oxford: ‘Society, by Jean Eliot’, Times Herald (Washington, DC), 31 August 1921. Record of Marriage: search for Aaron Bradshaw and Edith Doulton, 1919, Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl, accessed 5 October 2025.

[39] ‘One Bride, Two Bridegrooms’, Daily News (London), 8 January 1923.

[40] Note 21 above.

[41] The years of Howard Booker and Edith Gwendoline Doulton’s relationship can be determined from a US passport application made by Gwendoline Booker in 1917, in which Howard Booker states that he has known her for 8 years, and a passport applications made by Booker in November 1918, in which Gwendoline is still described as his wife, U.S., Passport Applications, 1792–1925, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025. Biographical details for Gwendoline Edith Doulton can be assembled from: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49127852/gwendoline-bradshaw, accessed 5 October 2025.

[42] ‘Alias Summons’, Wallace Miner (Wallace, ID), 12 May 1910.

[43] Barbara M Booker, Births, Marriages, and Deaths, 1924, search, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl, accessed 5 October 2025. The birth was registered some months after it occurred, but Barbara Booker’s date of birth is given in her entry in the 1939 England Register, Plymouth, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025. For world travel, we can point to trips to China in 1932 and 1934: entr for Howard E.Booker, Washington, King, Seattle, Passenger Lists, 1890-1957, 3 May 1932; entry for Ivy Gladys Booker, Vermont, Franklin, St. Albans, Canadian Border Crossings, 1895-1954, 30 December 1934. ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025.

[44] ‘Fort Meade’s First Girl Show Gets Enthusiastic Reception’, Baltimore Sun, 6 April 1941.

[45] Howard E. Booker, United States, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025. ‘SFer Seeks N.Y. Off-Track Betting’, San Francisco Chronicle, 27 August 1953. Howard E. Booker, California, Death Index, 1940-1997, 28 February 1976, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 3 October 2025. Ivy G Booker, Births, Marriages, and Deaths, 1966, search, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl, accessed 5 October 2025.

[46] ‘Old-Time Polo Star Billy Parsons Dead’, Evening Express (Portland, ME), 20 March 1925.

[47] ‘Notices’, Pall Mall Gazette, 24 May 1918.

[48] ‘The Baseball Rag’, Halifax Daily Guardian, 5 July 1918.

Howard E. Booker and his partner Edith Gwendoline Doulton, 1918. US Passport Application. Public Domain.

William A. 'Billy' Parsons, 1918. US Passport Application. Public Domain.

Billy Parsons and his 1898 New Bedford Roller Polo Team. Spalding's Official Roller Polo Guide, 1898. Public domain.

Dick Merriwell's Polo Team, 1906. Dime novel cover. https://dimenovels.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/dimenovels:341615. Public domain.

Garment of the A.R.C. workrooms at 36 Grosvenor Gardens showing English and American women making the last of a rush order for 300 baseball uniforms for American soldiers in camps throughout England, 1918. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Anglo-American Baseball League poster. Imperial War Museum. Used with permission. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/31749

Press photo, 4 July 1918 baseball game at Stamford Bridge. US National Archives. Public domain. http://catalog.archives.gov/id/16578410

Press photo, 4 July 1918 baseball game at Stamford Bridge. US National Archives. Public domain. http://catalog.archives.gov/id/16578420

Letterhead, London Baseball Association Ltd, included in US Passport application of William A. Parsons, 1918. Public Domain.

Anglo-American Football League? Letter included in US Passport application of William A. Parsons, 1918. Public Domain.

University baseball, England, 1919. Oxford Journal, 28 May 1919. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

University baseball, England, 1919. Daily News (London), 9 June 1919. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

The Baseball Rag. Referee, 30 June 1918. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.