Strongheart

Jamie Barras

Reader discretion recommended for quotes from period sources that use what we would recognise today as discriminatory language.

Hunslet's American Player, Lucius Banks, an athletic American, twenty-three years of age, weighing somewhere about 11st., arrived in Leeds on Saturday night from New York to join the Hunslet team. Banks who is credited with being able to do even time has been a prominent quarter back in American football, and is also an exponent of the game of baseball. He has seen service in the United States.[1]

The appearance of Lucius Banks, a coloured man from America, at three-quarters for Hunslet, created a great deal of interest, and he had the satisfaction of a try.[2]

The arrival of the first American to play rugby league at a professional level was also the arrival of the first African American to play the sport. As we will discuss here, the journey of this pioneering player was a remarkable one, placing him at the intersection of several movements in both American and British society and culture, particularly sporting culture, at the beginning of the Twentieth Century.

Lucius Banks Jr (1885/6–1955) was born in Harmony Town, Arlington, Massachusetts, near Boston, in 1885 or 1886 (the records are unclear which)—so, closer to 28 than 23 when Hunslet signed him. Historian Tony Collins has done much to discover the story of his life.[3] Banks attended Arlington High School, where he was on the school football, baseball, and track teams. By his own later account, on graduation, he transferred to Exeter Prep on a scholarship. Exeter, more properly the Phillips Exeter Academy, was a rare example in this period of an institution that accepted students of all races. It was also a stepping stone to a college education, and this may have been Banks’ goal; however, he lost the scholarship after only one month under unknown circumstances. It was at this point that he signed up for the army, becoming a trooper in the 9th Cavalry.[4]

The 9th Cavalry was one of the famous Buffalo Soldier regiments, US Army units of the period with white officers and Black NCOs and enlisted men that had seen service in the so-called ‘Indian Wars’ of the late Nineteenth Century. After the end of the ‘Indian Wars’, the 9th Cavalry saw service in the Spanish–American War of 1898 and was subsequently deployed to the Philippines several times between 1900 and 1916 to help suppress an indigenous independence movement that had arisen in response to the American occupation of the archipelago at the close of the 1898 conflict.[5]

It was in early 1907, on the eve of one of the 9th Cavalry’s deployments to the Philippines, that the decision was made to detach elements of the regiment for service at the US Military Academy at West Point. Several units of regular army soldiers served as instructors at the academy, representing different branches of the service at the time: infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The role of the cavalry detachment was to provide instruction to the cadets in riding, horsemanship, and cavalry maneuvers.

In late 1906 or early 1907, the US Army top brass decided to replace the existing cavalry detachment at the academy, which comprised white troopers, with one formed of Black troopers. In later years, this would be characterised as a decision borne of the recognition that Black cavalry regiments did not suffer the levels of indiscipline and desertion that plagued white regiments of the period. However, while it was undoubtedly true that the 9th Cavalry troopers and colleagues from other regiments who would join them in later years were dedicated soldiers, as well as excellent horsemen and skilled instructors—they would not have kept the role for 40 years otherwise—this was not the reason for their deployment. Instead, as was made plain in newspaper accounts of the time, they were selected as the troopers’ role at the academy included caring for the cadets’ horses as well as their own mounts, and the white troopers had long chafed at this, seeing it as marking them as servants, not soldiers. The US Army top brass opted to replace the recalcitrant white troopers with Black troopers based on the racist idea that Black troopers would not, could not, object to being treated as servants.[6]

We know from accounts from 9th Cavalry enlisted men attached to West Point that the early years of their deployment were not easy, principally because of the refusal of the other—white—enlisted men attached to the academy to see them as equals. In an early incident that was to spark much trouble to come, a combined group of enlisted men from the artillery, cavalry, and infantry detachments at West Point was detailed to help with the 1907 exposition in Jamestown, VA. While the white enlisted men of the artillery and infantry elements of the detail were allowed to enjoy the exposition when their work was done, the Black troopers of the cavalry element were made to remain in the stables and tend to the wagons and horses of the artillerymen. As one of the cavalrymen put it, ‘We are now waiting on the artillery instead of the cadets’. Over the following decades, there would be regular outbreaks of fighting between the artillery and cavalry detachments at West Point, some of which resulted in serious injury.[7]

There was a bright side to the deployment, however, and this was the many opportunities for playing sports. As the quote that opened this piece shows, the cavalry detachment at West Point had its own football and baseball teams. It also had its own cricket, track, polo, and basketball teams.[8] Their main opponents, at least in the early years, were teams from the other regular army attachments at the academy in the form of games played in enlisted men’s leagues (alongside, in the case of the polo team, games against the cadets, which may be considered as part of the cadets’ cavalry training). We can also point to, by the 1920s, games in the Hudson Valley area, at least as far as football, baseball, and basketball go, mainly but not exclusively against other African American teams.[9] There were also, by the 1920s, games in various sports in this period against teams from other African American US Army regiments stationed in the New York area, including basketball games against the famous ‘Harlem Hellfighters’ (the 369th Infantry Regiment).[10]

It is worth noting that, although the first Black cadet had entered West Point in 1870 (James Webster Smith; he did not graduate), and two of the first three Black cadets to graduate, John Hanks Alexander (graduated 1887) and Charles Young (graduated 1889), had gone on to serve as officers in the 9th Cavalry, by the time the 9th Cavalry NCOs and enlisted men arrived to serve as the academy’s cavalry detachment, the academy had effectively abandoned attempts to integrate the campus, something that would not be attempted for a second time until the 1930s.[11]

Banks served in the cavalry detachment at West Point from 1908 until 1912.[12] At some point in 1911, a member of the committee of the Hunslet Club, visiting New York on business, saw Banks quarterback a game for the cavalry detachment football team. At this early period in the detachment’s history, it seems likely that this was an enlisted men’s league game at West Point. Whatever the circumstances, the unnamed committeeman liked what he saw so much that arrangements were made for the club to purchase Banks’ discharge from the Army and offer him a contract with Hunslet. Banks accepted sometime around September 1911, and, in January 1912, set sail for England on board the RMS Oceanic.[13]

[American football] is not in any sense a question of recreation or sport. It is merely a most degrading exhibition of foxy cunning and brute force; and victory almost invariably rests with the side which has the fewest men put out of action. Let us be thankful that we have not reached such a stage in England.[14]

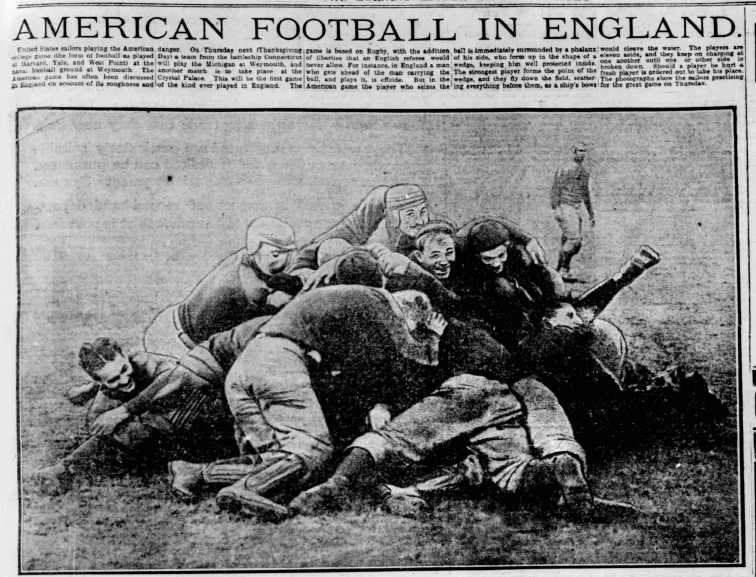

Banks was travelling to a country that, on the whole, as much as it gave any thought to the sport that had brought Banks to the attention of Hunslet, regarded it as a ‘barbarous product of a barbarous people’.[15] It is fair to say that few American sports were regarded highly in England in this period—baseball was famously described in the British press as ‘glorified rounders’—but none was so derided as what was known in England as ‘American football’. While British newspapers might from time to time carry American baseball scores, and, indeed, by 1912, there had been two (unsuccessful) attempts to introduce baseball as a summer sport in England (in 1890–1900 and again in 1906–1912),[16] the only mentions of American football in the British press were the annual ‘butcher’s bill’ of the number of players killed in the course of the most recent season in the US: 27 in the 1905/1906 season; 11 in the first month of the 1907/1908 season, 18 in the first month of the 1908/1909 season; a total of 113 across the last eight years leading up to January 1909, etc., etc.[17]

It is worth noting here that, although these casualty numbers should be viewed as suspect, the lethal nature of the sport was real enough, so real that there were serious considerations given in the US to banning it; efforts ultimately thwarted because the game was a money-spinner and vested (gambling) interests were loath to lose this revenue stream.[18]

Allied to the reports of the bloody nature of the sport in the British press were reports on the innovations in equipment designed to mitigate the damage players were inflicting on each other, presented as if a medieval vision of hell from a painting by Hieronymus Bosch.

What makes the player so grotesque, for he appears scarcely human, are the various forms of guards. He covers his head with a huge leather cap, which looks not unlike some cooking utensil. Over his ears are firmly drawn huge leather ear protectors. His nose is guarded by a large piece of india-rubber perforated for breathing [...][19]

It was somewhat ironic, therefore, given the lurid interest in the sport as Spectacle, that the first place that English spectators would get to see an American football player ‘in the flesh’ was not on the playing field but on the stage.

"I expect one scene in ‘Strongheart' to rouse your audiences to enthusiasm. It is a football match scene containing all the excitement of the game without showing the game itself. The dramatic interest of this scene shows a conspiracy to break down one of the teams. I do not think there has ever been such a scene on your stage." [20]

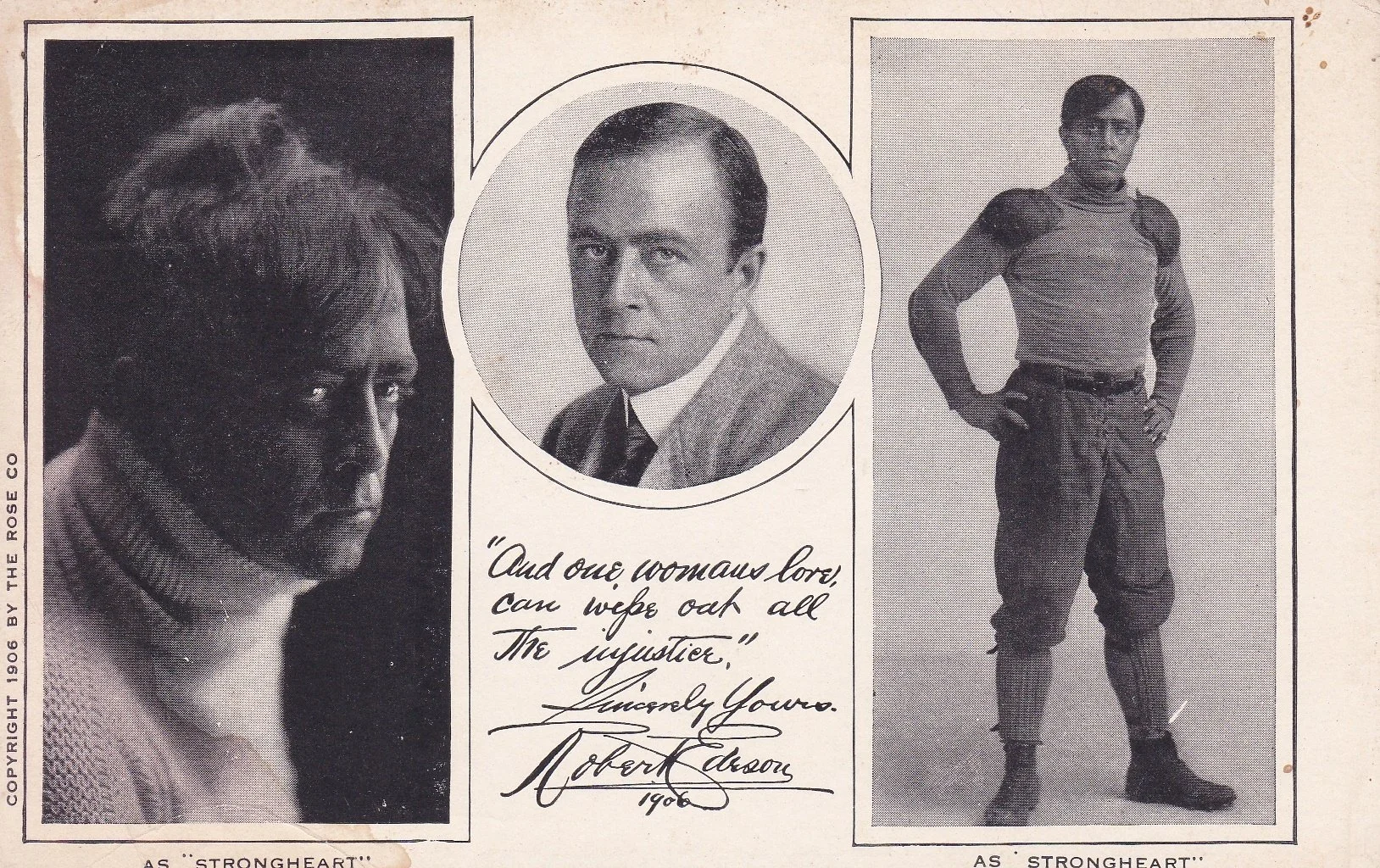

‘Strongheart’, first produced in the US in 1905 and brought to London by Charles Frohman in 1907, was billed as a ‘comedy drama’. It told the story of three days in the life of the titular character, aka Soangataha, a North American Indian and graduate of the Carlisle Indian School, who was pursuing a post-graduate programme at Columbia University, where he had become the star of the football team. The ‘B’ plot concerned a scheme concocted by one of the players on the team to fix the result of the ‘big game’ to win a bet; however, the real interest in the play in the period was in its ‘A’ plot, which centred on a romance between Strongheart and a white woman, Dorothy, the sister of the captain of the football team. In keeping with the views of the period, although the attraction is mutual, Strongheart ultimately decides against pursuing the romance when he is called back to assume the leadership of his people and it is made clear to him that they would not welcome a white woman as his bride, any more than Dorothy’s family would welcome Strongheart as her groom. In the language of the time, ‘Strongheart’ was a ‘racial play’. It found fault on all sides.[21]

The play was the work of William B. DeMille, brother of Cecil B. DeMille and a professor at Columbia, who drew inspiration from the real-life footballing exploits of the members of the Carlisle Indian School Football Team, stars of the varsity football scene in this period. DeMille may have been present when the Carlisle team played Columbia in 1901, a game that Columbia won.[22]

The whole of the second act was set in the Columbia team locker room on the day of the ‘big game’ and featured the actors—led by, in the role of Strongheart, white American leading man Robert Edeson in heavy ‘redface’ make-up—outfitted in American football uniforms of the era. Reviews in the British press made much of the attention to detail in the scene and how ‘instructive as to the methods of our footballing brethren across the Atlantic’ the ‘ear-splitting’ exchanges between the players and their coach were.[23] That no scenes of actual game play were shown—just described by Strongheart to a wounded teammate as he looks out of the locker room window—serves as a meta commentary on the fact that, at the time, this scene was as close as the audience could come to seeing a real American football game in England.

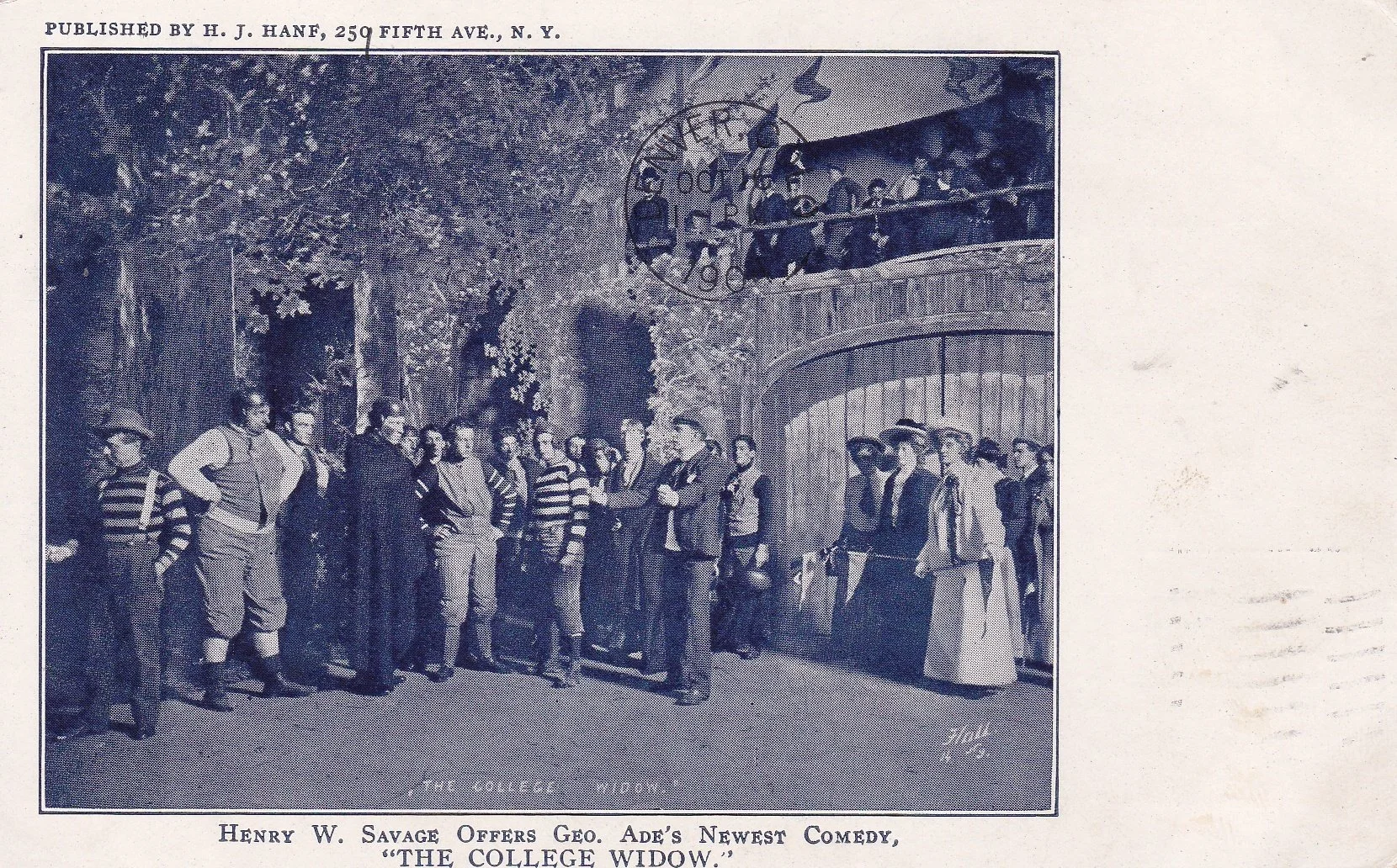

Of added interest to us here, ‘Strongheart’ was the second play with a plot centred on [American] football to debut on the American stage. However, the first, ‘College Widow’, by George Ade, only made the transfer to London after the success here of ‘Strongheart’, debuting at the Adelphi Theatre a year later, in May 1908. ‘College Widow’, dispensing with Strongheart’s attempt at a serious message, was a broad comedy centred on the attempts by the daughter of the president of Atwater College, the ‘college widow’ of the title (a slang term referring to a woman who specialised in romancing college students), exerting her ‘feminine wiles’ to persuade a promising football prospect to ignore his father’s desire for him to attend a rival college and attend Atwater instead. The third act presented a football game as seen through the eyes of the spectators who provide the theatre audience with a blow-by-blow account of the furious action on the field while various players mill about the sidelines (or are carried off the field, wounded—the butcher’s bill played for laughs). Thus, as with ‘Strongheart’, the London audience was presented with the experience of attending the game without seeing any of the game itself.[24]

Tantalisingly, however, it was reported in the British press while ‘College Widow’ was playing at the Adelphi that a game of American football might be played in London as ‘The members of two American theatrical companies now playing in London have threatened to meet in a match and they announce that “the game will be played as in America, and in the full armour of the Transatlantic battler.”’ One of those companies was almost certainly the ‘College Widow’ company, and the other, based on the timing, was likely to be that of the play ‘Way Out East’, which was playing at the Aldwych Theatre at the same time that ‘College Widow’ was at the Adelphi.[25]

Alas, it seems unlikely that the game ever took place. Conceived as a publicity stunt for the two shows, it was rendered redundant by the news that both shows would close early after receiving poor reviews (in the case of ‘Way Out West’, only one week into its run). Much like American sport, American humour did not go over with British audiences.[26]

British sports fans would have to wait another two years for their first taste of real American football action.

What a day for football training, with rain falling down like sticks of lead pencil at Greenhithe yesterday. Yet, for full three hours, the football team of the Idaho practised for their championship match with the Connnecticut at the Crystal Palace to-morrow.[27]

The story of the 1907–1909 circumnavigation of the globe by a force of US Navy battleships that became known as the ‘Great White Fleet’ is one of many layers; a successful publicity exercise that reinforced the message, first delivered by US victory in the Spanish–American War of 1898, that the US was now a naval power with global reach, it also laid bare the stark reality that, outside of the Atlantic, the US Navy’s coal-fueled battleships were completely reliant on the British mercantile marine for resupply; at the same time, this stark reality was one that the voyage’s architects, Teddy Roosevelt prime amongst them, wanted to bring home to the politicians in Washington who controlled the purse strings. Win–win.[28]

As one of the goals of the journey was to impress upon rising Pacific naval power Japan that the US was ready to meet any challenge, and Japan was an ally of Great Britain in this period, as a sign of its gratitude that the British government had authorised the leasing of British merchant ships to the US Navy as coal carriers, the conclusion of the circumnavigation was followed nine months later by a goodwill mission to Britain by elements of the fleet (the only part of Europe that the circumnavigation itself had included was the Mediterranean coast, including Gibraltar). As the visit would coincide with Thanksgiving, traditionally celebrated in the US military with football games (much as the 4th of July is celebrated with baseball games), a decision was made to stage games between teams formed of sailors from the battleships of the fleet during the visit. This led to four games being played, two on Thanksgiving (which, in 1910, was 24 November), at Weymouth in Dorset, and at the Crystal Palace sportsground in London, a week later, a third, ‘championship’, game sponsored by the Daily Mirror, played again at the Crystal Palace; and a final game, almost an afterthought, at Northfleet in Kent on 21 December.

Following a practice game at Weymouth on 21 November featuring teams from the USS Michigan, the Weymouth game on Thanksgiving was played between teams from the USS Connecticut and the USS Michigan; the Connecticut won 11–0. Meanwhile, the Thanksgiving Crystal Palace game was between teams from the USS Idaho and USS Vermont, and the Idaho emerged victorious, 19–0. The championship game, between the Idaho and the Connecticut at the Crystal Palace, a week after Thanksgiving, was won by the Idaho 5–0. The Northfleet game between teams from the USS Rhode Island and the USS Georgia ended in a victory for the Georgia, 11–0. Around 5000 people watched the Weymouth Thanksgiving game—albeit, at least 3000 of whom were sailors from the US fleet; attendance for the two London games was around double this number; attendance for the Northfleet game is unknown.[29]

Reactions to the games from the British press were mixed. The Daily Mirror, unsurprisingly, given that it sponsored two of the games, was keen to emphasise the athleticism and rugged determination of the players, and the interest and excitement of the spectacle. It devoted the front page and three inside pages of its 25 November 1910 edition to the first Crystal Palace game.

Before an enthusiastic crowd, 10,000 strong, the great American football match arranged by the Daily Mirror between teams from the American battleships Idaho and Vermont was played at the Crystal Palace.[30]

Everyone was greatly interested in the game at the Crystal Palace, which proved one of the most exhilarating sporting contests ever held in England. Even the spectators who were unfamiliar with the rules soon found themselves becoming excited and infected with the enthusiasm of the players.[31]

However, even the partisan Daily Mirror was unable to disguise the shock to English sensibilities of the sight of full-contact play.

The American game is entirely different to “Rugger” or “Soccer” in every way. No doubt, after playing it half a dozen times, the survivor, if he survived, would understand the thing properly. One thing is very certain, anyway: the game is a game for men—men as the Romans used the distinction between real men and just humans of the male sex.[32]

Meanwhile, newspapers will less cause to be generous than the Daily Mirror lent heavily into the old tropes of the blood and violence of the spectacle.

The impression conveyed could hardly have been one which will lead us to forsake our present Rugby code, for most of the checks imposed on our players are not put upon the Americans, while the play is so rough that a number of substitutes are taken to the field of play to fill up the gaps left by the wounded.[33]

The Times, as ever, took a particularly high-minded view.

The game is the direct descendant of all-in football of our ancestors, of which the worthy Stubbes (1583) said in his “Anatomie of Abuses in the Realm of England”:—"I protest unto you that it may rather be called a friendlie kinde of fyghte than play or recreation—a bloody and murthering practice than a felowly sport or pastime.” . . One must needs feel amazed and a little amused that the Americans should be playing 16th century football in this century. Really, it is rather unprogressive.[34]

Quite. Perhaps understandably, given that their readers would be entirely unfamiliar with how the game was played, newspapers devoted few column inches to describing the games themselves. Perhaps the most extensive report was the account of the Weymouth game in the Dorset County Chronicle that, in amongst long diversions into describing the musical accompaniment provided by the attendant marching bands and cheerleaders, did at least describe the two plays that produced the game-winning points.

The Connecticut men drew first blood in the first quarter of an hour. That is to say, they scored five points from a touch down, but the resultant, flying kick, which might have converted this into a goal of six points, went wide of the cross bar […] The Connecticut team pursued their advantage further, as their band struck up “Teasing, teasing, I was only teasing you;” and late in the second quarter, they scored six more points from a touch down. This was really the extent of the scoring in the match; but the Michigan men stuck to their work grimly up to the fifteen minutes interval.[35]

Notably absent from any account was any suggestion that the game might be adopted in England. Sidestepping the question of the violence, the Daily Mirror columnist who described the game as being for real men declared its long interruptions in play an anathema: ‘there is too much time wasted while the two sides are formed up after a tackle’.[36]

This latter point is interesting as the frequent interruption in play in baseball games brought about by the ‘three-outs-all-out’ rule was often cited as a major reason why baseball never found favour with British sports fans.[37] It is also telling in this regard that when Rugby League separated from Rugby Union over the issues of payments to players and found itself in need to make the game more appealing to a paying crowd, it chose to abandon line-outs to keep the ball in play, and thus the game in motion, for as long as possible (the ball is in play for up to twice as long in League games as in games under the Union code).[38] Extending this point, while acknowledging that each sport has its adherents both in England and the US, one could argue that the reason there was no point in bringing American football to England in the early part of the Twentieth Century was that England already had Rugby League. It didn’t need new sports, it needed new players.

[…] a special word of praise is due to the black recruit, Banks, who, with the exception one foolish blunder, played with the skill necessary of an accomplished wing three-quarter. He is treated with the utmust generosity by his captain, an important factor of which he rarely fails to take advantage. His brilliant dashes provided the chief excitement of the afternoon, and he was most unlucky not to have at least a couple of tries to his credit.[39]

Lucius Banks’ captain that first season at Hunslet was the great Billy Batten, one of the finest players that Rugby League ever produced.[40] The support given to Banks by his Hunslet teammates unquestionably contributed to how quickly and how well he adjusted to the new game. Added to this was how warmly he was greeted by the Hunslet fans.

There was an attendance of over 2,000 (both stands were well occupied), the appearance of Lucius Banks, Hunslet’s coloured American, proving an attraction. Although Banks did not shine very often, he being too well watched by Garforth, he scored a splendid try, and was evidently well pleased with the cordial recognition given to his effort.[41]

This is not to say that racism did not rear its ugly head in Banks’ time in Yorkshire. The local Yorkshire Post stable of newspapers produced two articles immediately following news of his recruitment that reeked of racism, one with the headline ‘Hunslet’s Coloured Coon’, and another that railed against the recruitment of foreign players when there were plenty of Yorkshiremen who could play the game—nevermind that one of Banks’ teammates was an Australian—while pondering odiously why, if recruiting Black players was so desired, Hunslet did not recruit them from South Africa, as they ‘may cost nothing in shoe leather, seeing that they are reputed to be capable goal kickers with bare toes’.[42]

To the Yorkshire Post’s credit, when Banks left Hunslet to return to the United States, the Evening Post lamented his departure, saying that ‘he will leave a good many friends behind him at Parkside’.[43]

Banks also received more than his fair share of barracking from opposing fans.

I remember a certain match—a semi-final at Huddersfield—when a player of the name of Lucius Banks, a coloured gentleman and a really good sport, was barracked unmercifully by a section of the Huddersfield spectators simply because of his colour. Remarks were made all through the game which were not in keeping with supporters of such a brilliant team as Huddersfield.[44]

Banks showed little sign that he was affected by this negative attention. Still a novice at the game, he excelled at those parts that were familiar to him (running and scoring—his real weakness was in kicking).

Banks, the coloured player, is as yet somewhat strange to the game. He was good and had in turns, but there was no mistaking his intentions when he did get the ball. He possesses pace and knows how to cut through. Of his kicking and re-passing, I saw nothing for when Banks got the ball, he meant business himself.[45]

And his partnership with Billy Batten went from strength to strength.

But now play went more to W. Batten's wing, and after good passing, Banks went over. (Greatly to the surprise of the crowd, he was called back, but Mr Robinson had rightly penalised a clear case of obstruction when Banks received his pass from W. Batten). However, the due reward of persistency was to come to the American, for another attack by the Rovers was taken advantage of by Hunslet. W. Batten got away in one of his characteristic rushes, and when opposed by Carmichael, threw the ball to Banks. The wing man made a good acceptance and raced finely away, finishing up between the goalposts.[46]

Alas, the good times were not to last. For unknown reasons, Banks was to start but not finish a second season with Hunslet. Modern commentators have speculated that these arose from a combination of homesickness and his isolation as the only African American in a relatively small English community, and it is worth pointing out in this context that he had a new wife (West Point nurse Caroline Grey) and a child he had never seen (James Orville Banks) waiting for him back in the States.[47] There is some evidence of decline in form from his first to his second season, which may be indicative of some kind of malaise or other distraction (although see below for an alternative explanation).

He was poorly supported by Banks, and much of his aggressive work was thrown away by the inability of the coloured man to take his passes. And Banks also sinned in that he rambled from his position far too much. Jenkinson, on the other wing, was just as convincing as Banks was feeble.[48]

This is not to say that Banks was not still capable of wowing the crowd.

Lucius Banks “brought down the house” by successfully emulating W. Batten’s trick of jumping over an opponent.[49]

And he was considered to be in good enough form to receive a cap for Yorkshire in a game against Lancashire in December 1912.[50] A possible alternative explanation for Banks’ seeming malaise is one built on the differences between the American and the English games, specifically, concerning tackling. It is noticeable how often game reports mention that opposition forwards were quick to tackle Banks after he received the ball.

[…] they seemed intent on giving their ebony coloured colleague, Banks, an early opportunity of scoring. But the tackling of some of the Bramley players was much too strenuous and sure, and Townsend, Turton, and Haley especially emphasised this.[51]

[Banks] was well watched, and one or two of the Rochdale backs did not treat him with absolute fairness.[52]

Of course, this was just sound tactics for dealing with a dangerous player known to favour running with the ball over passing or kicking. However, Banks would have been used to having his forwards run interference for him when he was quarterbacking for the cavalry detachment back in the States, and would have been able to rely on a degree of protection from the equipment and guards so derided by the British press. In League matches, his only protection was his speed, which served him poorly when targeted by multiple, converging backs. In short, what observers saw as malaise, fumbling of the ball, and wandering from position may actually have been concussion.[53]

Lucius Banks left England for home on New Year’s Day 1913.[54]

The sports concluded with an exhibition of baseball by the U.S. naval men, followed by a display of American football. To probably the majority of those present, it was the first time they had witnessed a game of American football, and it consequently aroused a considerable amount of interest. The game consists of a series of scrimmages, and play is exceptionally hard and keen.[55]

American football returned to Britain with the return of the US Armed Forces in the final year of the First World War. Exhibition games, often in association with baseball games, were played in aid of charity up and down the length of the country. The highlight was once again the games played at Thanksgiving (two weeks after the signing of the Armistice), particularly that at Stamford Bridge in London. The game was originally intended to be between teams from the Army and Navy; however, demobilisation of US forces was so rapid that the Army had to withdraw from the game, and it instead took place between US Navy teams representing the destroyer flotilla and battleship division; the game ended without any points being scored.[56]

When the US Armed Forces returned to the US, they took their football with them. There it would remain until the next world war. It was only with the advent of television, which made it possible for fans from all over the world to connect with the game, that interest in the sport really took off in Britain. Regular-season games played in London are now an annual feature of the NFL schedule.[57] However, it is still very much only of niche interest to British sports fans, and, even today, one doesn’t have to search far to find fans of other football codes who deride it for its frequent interruptions in play and use of body protection. Plus ça change…

On his return to the US, Lucius Banks signed up for the US Army for the second or third time (accounts differ). By his own account, the entry of the United States into the First World War saw him at an officer training school in the Philippines. He was transferred to the predominantly African American 349th Field Artillery Regiment as a sergeant, where his commanding officer recommended his promotion to first lieutenant. He saw active service with the 349th in France in 1918. Much of this account can be corroborated from US Army Transport Service records, which confirm that Banks served in the 349th Regiment’s headquarters company as a 1st Sergeant and saw service with the 349th in France, from June 1918 until February 1919. There is no record of a commission, but this may have been a temporary field commission.[58]

After the war, Banks moved to Boston, where, in 1919, he became one of the men drafted into the Boston Police Force by Governor Calvin Coolidge to break a police strike. Unsurprisingly, as a ‘scab’ (strike breaker), after the strike ended, moves to get rid of him began. The excuse finally came in 1926 when he arrived at his post 20 minutes late—by his own account, because he had stopped to break up a fight along the way. His explanation was ignored, and he was fired. He found work as a redcap (railway porter). By 1932, he was in such dire financial straits, in part because of his growing family, that he sought help from his former commanding officer and other prominent figures to bring about his reinstatement in the police force. This campaign culminated in a bill being put before the Massachusetts State House of Representatives to have him reinstated. The bill passed 130 votes to 57 and survived an attempt by the state governor to veto it. Banks was duly reinstated and spent the rest of his working life as a police officer in Boston. He retired in 1944 and returned to his hometown of Arlington, Mass, with his family. When he died there in February 1955, flags were flown at half-mast at the town hall, police station, and fire station.[59]

In 2024, Hunslet Rugby League Football Club (actually a successor to the original club, which folded in 1973) invited Lucius Banks’ grandson, Richard Lucius Banks Jr, and his family to a presentation at the new Parkside stadium. Banks Jr is a lawyer, like his father before him, Richard Lucius Banks Sr, who ended his career as a judge.[60]

Thanks in no small part to the efforts of historian Tony Collins, Banks is now receiving increasing attention as a pioneering sportsman. Not before time.

Jamie Barras, August 2025

Back to The Spectacle

Notes

[1] ‘Hunslet’s American Player’, Bradford Daily Observer, 22 January 1912.

[2] ‘The Northern League’, Yorkshire Factory Times, 2 February 1912.

[3] Podcast on Banks by historian Tony Collins: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/82-lucius-banks-americas-first-pro-rugby-player-black/id1358627156?i=1000453409425, accessed 15 August 2025.

[4] This account of Banks’ early life is taken from ‘“Red Cap” Put Back in Police Force’, Boston Globe, 6 October 1932. It has to be acknowledged here that there are elements of the account of Banks’ later life in this report that are verifiably incorrect, which must be borne in mind when considering the account it gives of his early life. Exeter Prep: https://exeter.edu/about/, accessed 14 August 2025.

[5] https://1cda.org/history/history-9cav/, accessed 14 August 2025.

[6] For a modern take on Black troopers in cavalry detachment at West Point, see: Michael E. Ruane, ‘West Point Football was all-White until 1966. So Why Does this 1920s Photo show an all-Black Squad?’, Washington Post, 22 February 2021; for the view at the time (1907), see: ‘Negroes May Go to West Point’ Leavenworth Times, 14 February 1907; ‘Negro Troops at West Point’, Watchman and Southron (Sumter, SC), 27 March 1907.

[7] The Jamestown story come from a letter sent to the African American press by ‘a cavalryman’, ‘Contempt for Black Soldiers at West Point’, Topeka Plaindealer, 21 June 1907; fights between artillery and cavalry detachments: see Note 5 above, first reference; serious injuries: ‘A Fierce Fight at West Point’, Springfield Daily Republican, 14 May 1911.

[8] Banks was said to have played cricket at West Point: ‘Retired Police Officer Buried’, Afro-American, 26 February 1955; for the cavalry detachment polo team, see: ‘West Point Cavalry Celebrates Birthday’, Chicago Defender, 4 April 1931; basketball: ‘In the World of Sport’, New York Age, 14 December 1911. Track team, also polo team playing cadets: ‘Cavalry Unit at West Point is Rated High’, Afro-American, 1 February 1930.

[9] See, for example, for basketball, Note 7 above, second reference; for baseball, there were games against Negro league team Hilldale Athletic Club (the ‘Darby Daisies’): Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia, PA), 18 July 1921. Hilldale: https://negroleagues.org/hilldale-club, accessed 14 August 2025. A rundown of the football’s achievements in the 1920s can be found in Note 5 above, first reference, and ‘A Real Football Team’, Chicago Defender, 20 January 1923. Games against white/predominantly white teams include football games in New Jersey against the West Side Athletic Club: ‘U.S. Cavalry Loses, Chicago Defender, 5 December 1925; and pro team the Passiac Red Devils: ‘Cavalry Tops Passiac Pros’, Afro-American, 13 December 1930.

[10] ‘Big Athletic Affair Will Be Held In Harlem’, New Pittsburgh Courier, 28 March 1925.

[11] Patri O’Gan, ‘Duty, Honor, Country: Breaking Racial Barriers at West Point and Beyond’, National Museum of African American History & Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/west-point, accessed 14 August 2025.

[12] His service at West Point can be confirmed from the list of enlisted men ‘Discharged by Order’ for West Point, where the date of his discharge is given as 4 April 1912: U.S., Returns from Regular Army Non-Infantry Regiments, 1821-1916, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 15 August 2025

[13] Circumstances of Banks’ recruitment by Hunslet: Note 3 above, first reference; and the work of Tony Collins, discussed here: https://southleedslife.com/hunslet-reflect-on-the-ground-breaking-lucius-banks-in-black-history-month/, accessed 15 August 2025. Banks is listed among the passengers on the Oceanic, arriving Pymouth 20 January 1912, UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 10 August 2025. His occupation is given as ‘athlete’.

[14] ‘American Football’, Sheffield Daily Gazette, 26 December 1908.

[15] This is actually the description of a play with a plot centred on American baseball, but it serves as well as a description of the game as seen through British eyes: ‘American Invasion’, John Bull, 2 May 1908.

[16] I cover the history of attempts to introduce baseball into Britain in my Diamond Lives series: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives, accessed 14 August 2025. For an academic treatment of British reactions to the sport, see Daniel Bloyce, ‘That’s Your Way of Playing Rounders, Isn’t It? The Response of the English Press to American Baseball Tours to England 1874— 1924’, Sporting Traditions, 2005, 22, 81–98.

[17] ‘American Football’, Holloway Press, 23 February 1906; ‘Strenuous Football’, Halifax Daily Guardian, 7 December 1907; ‘Strenuous Sport’, Daily Record, 14 December 1908; for compiled figures, see Note 12 above.

[18] E.A. Harrison, The first concussion crisis: head injury and evidence in early American football, Am J Public Health. 2014 May;104(5):822-33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301840. Epub 2014 Mar 13. PMID: 24625171; PMCID: PMC3987576.

[19] ‘American Football Armour’, Sheffield Weekly Telegraph, 29 April 1905.

[20] ‘Mr Frohman’s Futures’, The Referee, 21 April 1907.

[21] Plot summary of ‘Strongheart’: ‘Strongheart’, Era, 11 May 1907. ‘Racial Play’: ‘Strongheart: Racial Play at the Aldwych’, Morning Leader, 9 May 1907.

[22] William B deMille: https://www.ibdb.com/broadway-cast-staff/william-demille-14586, accessed 14 August 2025. Carlisle Indian School Football team: Sally Jenkins, ‘This Footbal Team Shows What We Lose When We Ignore Our Real History’, Washington Post, 20 April 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2025/04/20/carlisle-indian-school-football-history/, accessed 14 August 2025. Columbia v Carlisle: ‘College Football News’, Sun (New York, NY), 30 November 1901.

[23] See Note 18 above.

[24] Plot summary of ‘College Widow’: ‘College Widow’, Era, 25 April 1908.

[25] ‘American Football in London’, Birmingham Mail, 14 May 1908; Way Out West and College Widow playing in London at the same time: ‘A Stage Invasion from America and France’, Sphere, 2 May 1908.

[26] ‘American Plays Fail’, Weekly Dispatch (London), 10 May 1908.

[27] ‘American Football Championship’, Daily Mirror, 2 December 1912.

[28] Christopher McMahon, “THE GREAT WHITE FLEET SAILS TODAY?: Twenty-First-Century Logistics Lessons from the 1907–1909 Voyage of the Great White Fleet”, Naval War College Review, 2018, 71, no. 4, 67–90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26607090.

[29] Practice game: ‘American Football in England’, Morning Leader, 22 November 1910; Weymouth game: ‘Weymouth: the American Fleet: American Football at Weymouth’, Dorset Chronicle, 2 December 1910; first Crystal Palace game: ‘Great American Football Match’, Daily Mirror, 25 November 1910; second Crystal Palace game: ‘Idaho Beats Connecticut’, Daily Mirror, 5 December 1910; Northfleet game: ‘Northfleet: American Football’, Gravesend and Northfleet Standard, 23 December 1910.

[30] See Note 27, third reference.

[31] ‘Some Incidents in Yesterday’s Great American Football Match’, Daily Mirror, 25 November 1910.

[32] ‘American Football at the Palace: An Impressionistic View’, Daily Mirror, 25 November 1910.

[33] ‘American Football in London, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 3 December 1910.

[34] Quoted in: ‘American Football “Rough to a Degree”’, Luton Times and Advertiser, 2 December 1910.

[35] See Note 27, second reference.

[36] See Note 30 above.

[37] Indeed, this was the principle reason that a ‘rival’ baseball code, ‘English Baseball’, developed in England and spread to Wales, one that abandoned the three-outs-all-out rule. I describe the development of the ‘rival’ code here: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-intolerance, accessed 15 August 2025.

[38] Story of the split between the Union and the League: Tony Collins, “Myth and Reality in the 1895 Rugby Split”, The Sports Historian, 1996, 16 (1), 33–41. doi:10.1080/17460269609446392. Differences between the codes: Joe Harvey, ‘Rugby Union v Rugby League: What’s the Difference?’, Rugby World, 27 May 2025, https://www.rugbyworld.com/news/rugby-union-v-rugby-league-whats-the-difference-174980, accessed 15 August 2025.

[39] ‘Hunslet’s Honour’, Leeds Mercury, 15 April 1912.

[40] ‘Billy Batten Dies: One of the Greats of Rugby League’, Hull Daily Mail, 28 January 1959.

[41] ‘Batley ‘A’ Again Victorious: Hunslet Reserves Defeated at Mount Pleasant, News (Batley), 17 February 1912.

[42] ‘Hunslet’s Coloured Coon’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 26 January 1912; ‘Hunslet’s Strange Policy’, Yorkshire Post, 29 January 1912.

[43] ‘A Few Hunslet Items’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 21 December 1912.

[44] ‘Hunslet Will Welcome Wrigley’, letter to the Yorkshire Evening Post, 9 January 1914.

[45] ‘A Great Decline, Athletic News, 18 March 1912.

[46] See Note 43 above.

[47] Modern commentators: see Collins, Note 11 above, second reference. Wife and child: entry for Lucius Banks, 29 September 1911, New York State, Marriage Index, 1881-1967, and entry for James o Banks, 1920 US Federal Census, Wheeling, West Virginia, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 15 August 2025. The marriage would not last, and Banks would marry again 1924, see Note 7 above, first reference.

[48] ‘Hunslet’s Happy Hustle’, Athletic News, 9 December 1912.

[49] ‘Hunslet V. Bradford’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 20 November 1912.

[50] ‘County Championship’, Wigan Examiner, 21 December 1912.

[51] See Note 43 above.

[52] ‘Hunslet’s Triumph’, Leeds Mercury, 8 April 1912.

[53] See Note 16 above.

[54] Entry for Lucius Banks, passenger lists for the RMS Megantic, arriving new York, 17 January 1913, New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 15 August 2025.

[55] ‘For Cameron Prisoners of War’, Northern Chronicle, 7 August 1918.

[56] ‘World of Sport’, Daily Mirror, 27 November 1918; Daily Chronicle (London), 29 November 1918.

[57] https://www.nfl.com/international/games/london/, accessed 18 August 2025.

[58] See Note 3 above, first reference, and Note 7 above, first reference. 349th in France: Richard Hulver,

‘Trailblazers, advocates and the anguished: Veteran profiles of the 349th Field Artillery’, https://news.va.gov/85065/trailblazers-advocates-anguished-veteran-profiles-349th-field-artillery/, accessed 15 August 2025. Banks’ transport records: U.S., Army Transport Service Arriving and Departing Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 15 August 2025. That this is the correct Banks can be confirmed by the name and address of his emergency contact (his mother, Julia Banks).

[59] See Note 3 above, first reference, and Note 7 above, first reference. Boston Police strike: Dave Shribman, ‘100 Years Ago, Boston Police Strike Raised Questions’, https://eu.detroitnews.com/story/opinion/2019/09/05/opinion-100-years-ago-boston-police-strike-raised-questions/2211505001/, accessed 15 August 2025.

[60] https://hunsletrlfc.com/general/hunslet-welcome-lucius-banks-family/, accessed 15 August 2025.

Lucius Banks in 1912 while playing for Hunslet Rugby League Club. Athletic News, 25 March 1912. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Photograph of West Point cavalry detachment football team, 1925-1926. US National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/239940159.

Photograph of West Point cavalry detachment football team, 1925-1926. US National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/239940157

Scene from Act III of 'Strongheart'. Public Domain.

Robert Edeson as "Strongheart", 1905. Postcard, author's own collection.

George Ade's 1904 play "College Widow". Postcard, author's own collection.

British view of American Football protective guards. Freeman's Exmouth Journal, 6 February 1898. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

American football players of the Battleship USS Michigan at Weymouth in Dorset. Morning Leader, 22 November 1910. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Baseball and Football together, World War One. Inverness Courier 2 August 1918. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

American Football in London. Pall Mall Gazette, 26 November 1918. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Lucius Banks in his Boston Police Department uniform, 1939. Boston Guardian, 22 April 1939. Image courtesy of Library of Congress. Public domain.