The Cooler

Jamie Barras

Content warning for quotes from period sources that use what we would recognise as slurs today

Schadenfreude dogged Frank Craig (1868–1943) his whole adult life. As a Black athlete in a white man’s sport—boxing—active in an era when it was widely believed that Black people did not experience pain in the same way as white people, which gave Black boxers an unfair advantage, his defeats at the hands of white fighters came to be more celebrated than his victories. Even the African American press, seeing Craig enjoy the trappings of success, too often chose to warn that pride comes before a fall rather than celebrate his hard-won gains.[1]

In telling the story of Frank Craig, one of the most successful African American boxers to make England his home, while acknowledging the forces surrounding him that played a role in shaping the course of his life, I want to focus on the decisions that he himself made, some good, some very, very bad, to separate the man from the moral lesson. This then is the life of Frank Craig, the man they called the Harlem Coffee Cooler, in all its messy complexity.

OUR COLORED CHAMPIONS. The first pair were middle weights. They were Frank Craig, Carmine A.C., and J.H. Johnson of Thompson Street. They proved to be a well matched pair, and the fight was very interesting in consequence. Craig had entirely the best of the first round, doing all the leading, and swinging widely if not effectively. The judges picked Craig for the winner. […] Ulysses Simpson Grant Mack, Berkeley A.C., and Frank Craig of New York were the next pair. They sparred the final bout of the middle weight class. It was bang, slap, punch, clinch and jump all through the bout. The judges agreed on Craig. The latter thus is the [middle weight] champion.[2]

By the time that Frank Craig defeated ‘Grant’ Mack at Robinson’s Gym in Brooklyn to become the middleweight ‘colored amateur boxing champion’ of America in November 1890, he had, or so the stories go, already been boxing for nearly a decade, having first stepped into the ring at the age of 14 and fought as an amateur across America under various names to disguise his youth. The truth of these stories is as contested as the date and place of his birth. Keen to emphasise his early promise as a fighter, Craig would routinely shave two years off his actual age, claiming to have been born on 1 April 1870. He (or his management) also claimed that he was the ‘son of a Red Indian mother and a Cuban negro’. However, based on official documents, we can say that Craig’s most likely date and place of birth were 1 April 1868 in New York City; his full name was Frank Walter Craig; and he was the son of Luke Craig, a miller.[3]

The origins of his ‘Harlem Coffee Cooler’ nickname are every bit as disputed. In his excellent article on the career of Frank Craig ‘Frank Craig “The Harlem Coffee Cooler”: Do You Take Your Boxing Legends With One Lump or Two?’, Chris Benedict opts for the story that, many years later, Craig’s contemporary, Black Canadian boxer George Dixon told writer Nat Fleischer, that a street tough had confronted Craig in a Harlem café and invited him to step outside, telling the café’s other customers that he would be back before his coffee cooled; instead, Craig flattened him. However, much earlier, within a few years of his professional debut in 1891, Craig had stated that he himself had coined the name. In this version, when asked for his name by a reporter just before his first professional fight, loath to give his real name as usual, Craig instead cast about for something else to say; looking out the window, he saw a man drinking a cup of coffee and, on the spur of the moment, blurted out ‘the Coffee Cooler’. In yet another version, sports writer Macon McCormick claimed that saying that a soldier was ‘only good for cooling coffee’ was an insult current in the military at the time of the American Civil War, and the man who would become Craig’s manager, Denny Butler, on seeing Craig fight for the first time and not being impressed, had dubbed him the Coffee Cooler. Finally, in later years, it was said that, in the days before he took up boxing, a down-on-his-luck Craig had begged a lunch counter owner for a job. The proprietor told Craig in jest, ‘Sure, you can work as a coffee cooler’; the story followed Craig around to be remembered when he took up the fight game.[4]

As ‘Coffee Cooler’ was indeed a Civil War-era nickname for poor-quality soldiers (men who sat at the side of the road waiting for their coffee to cool while their comrades marched into battle[5]), I am personally inclined to believe the version in which his future manager, Denny Butler, coined the nickname the first time he saw Craig fight.

Dennis F. ‘Denny’ Butler (1856–1913) was a fixture on the New York fight scene and the key figure in Craig’s early career; he helped Craig turn professional, trained him for the first four years of his professional career, and brought him to England.[6] Butler was a former Philadelphia police officer and professional swimmer and boxer who, when his days as an athlete were over, turned to sports promotion and boxing management operating out of the New York Athletic Club (N.Y.A.C.), where his brother-in-law, boxing great ‘Professor’ Mike Donovan (Michael J. O’Donovan (1847–1918)), was the boxing instructor. Craig was a frequent participant in the fight cards that Donovan and Butler put together at the N.Y.A.C. and the Lenox Lyceum in the early 1890s, fighting both white and Black opponents. In 1892, he even boxed at a benefit for Mike Donovan at which Donovan himself took on Gentleman Jim Corbett, who had just become the first heavyweight champion of the world under the Marquess of Queensbury Rules. As we will see, Butler’s time as Craig’s manager would end in acrimony in late 1894; not long afterwards, Butler gave up on the fight game and returned to Philadelphia and policing.[7]

The most significant fights that Butler arranged for Craig in the US were those against Philadelphia boxer Joe Butler, the reigning [unofficial] ‘world colored middleweight champion’. Craig lost the first but won the second, in February 1894, to take the title for himself. However, rather than defend the title, he instead faced a number of white fighters across the spring and summer of that year, culminating in him making an ill-judged attempt to go up a weight class and take on heavyweight Peter Maher (who was 20 pounds heavier at the weigh-in). That bloody defeat marked the end of the first phase of Craig’s American career, during which he had had 39 professional fights, winning 25, losing 10, drawing 2, with 2 no contests.[8] Within a month of the Maher fight, he was on his way to England.

FRANK CRAIG, the Coffee Cooler, is about due in England. He comes here to take on John O'Brien, the Welsh champion, in a twenty-round contest at 11st 4lb. He is the best of the representative middle-weights of the States, and the only man whom he bars when challenging the world to a fight is Bob Fitzsimmons. The Cooler is accompanied by his friend and adviser Denny Butler, who himself is a clever boxer and swimmer.[9]

Craig’s journey to England to fight John O’Brien was arranged by Mike Donovan on a visit to London in late July, just two weeks after Craig’s loss to Maher. This appears to have been the culmination of a plan that had been in place since the Spring, although at that time (before Craig’s pummelling at the hands of Maher), the idea had been that Craig would travel to London with Donovan. Regardless, the deal was struck in the offices of the Mirror of Life newspaper for the Craig–O’Brien fight to take place at the National Sporting Club in London in October. Although unreported at the time, the Mirror of Life’s editor, Bostonian Ed Holske, became an equal partner in the enterprise—of which much more later.[10]

It has been suggested based on Donovan’s role in this deal that he may have had a financial stake in Craig’s career in partnership with Butler; however, he was at the time described as a ‘friend and adviser’ to Craig, so the exact nature of their relationship remains uncertain. We can be fairly certain, given subsequent events, that, when Craig and Butler arrived in England on board the Mohawk in early September, Butler (and Donovan?) intended this to be only a visit, a chance to rebuild Craig’s career following the Maher defeat by taking on and beating the two best middleweights in Britain, O’Brien and Ted Pritchard, before a triumphant return to the US fight scene.[11]

It should be noted here that Frank Craig was far from being the first Black boxer to make his way to Britain; he was not even the first specifically African American boxer to fight in Britain—the most famous fighter of colour who preceded Craig to Britain, Tom Molineaux, was American, as was the man who was Molineaux’s trainer in England (albeit born in Colonial America), Bill Richmond. However, men like Molineaux and Richmond, and much less-well-known fighters like Jem Haines and Jack Davenport,[12] belonged to an earlier era, an era when professional boxing was still a bare-knuckle sport. Craig began his professional career in the US just one year before Gentleman Jim Corbett became the first heavyweight champion of the world under the Marquess of Queensbury Rules, which mandated the use of gloves and regularised the length and number of rounds, length of counts, outlawed grappling, etc., and marked the birth of the modern sport. He was schooled in the modern, furious American school of boxing, as he was to demonstrate.[13]

It was plain to all present that O’Brien stood no earthly chance. Still, he gamely struggled to avert the inevitable, but the Coffee Cooler would brook denial, and three times more O’Brien was sent to the boards. The sixth fall proved a settler, and as at the expiration of the allotted time, the Welsh champion was still prostrate, the referee declared Craig the winner of the contest.[14]

Craig and O’Brien met at the National Sporting Club on 8 October 1894. It was obvious to all assembled that Craig was the far superior fighter and in much better physical condition.

The visitor’s performance proved a complete surprise, and the only excuse that the Welsh division could offer for the defeat of their champion was that he had not sufficient time in which to get himself in proper condition. Be that as it may, O’Brien suffered greatly by comparison with his opponent, who, from the very opening clearly asserted his superiority at all points, and eventually won without receiving so much as a scratch.[15]

The contest, which lasted only one and a half rounds, was dominated by Craig (who fought wearing a sash bearing the Stars and Stripes). It was above all else a demonstration of the difference in the British and American boxing styles in this new age under the Queensbury Rules; something that Craig himself identified in an interview given a few weeks after the contest.

We fight differently in America to what your men do here […] because I notice none of them go in for a sharp decisive battle. I always like to settle my man in short order, and, in fact, all the Yankees are about the same. The fighters here work for a prolonged mill, and when they meet a hurricane fighter they always come to grief.[16]

The fight report in the journal of record for boxing in England in the period, the Sporting Life, was, for all its use of terms to describe Craig that we would consider slurs today, also favorable towards Craig. At this early stage of his career in England, with just one victory under his belt, there was none of the angst about the victory of a Black fighter over a white fighter that would characterise not just Craig’s later career but the career of all the Black boxers that would follow him, culminating in a ban on boxers of colour taking part in title fights in England that would stretch from 1911 to 1948.[17]

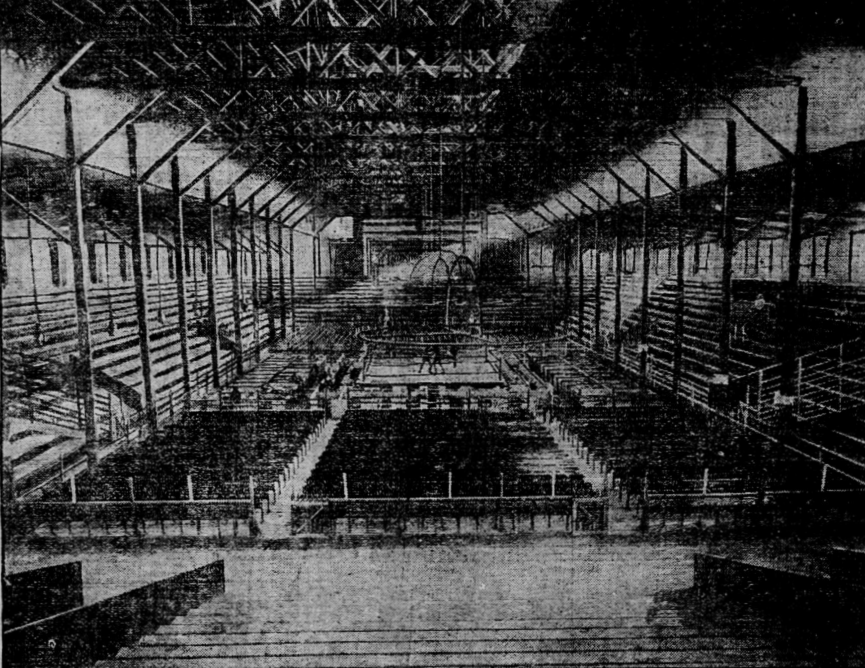

Immediately after Craig defeated the Welsh middleweight champion, O’Brien, Butler and Holske issued a challenge on his behalf to the English middleweight champion, Ted Pritchard, for a £500 purse (up from £150 for the O’Brien fight; at the time, in Britain, £500 represented around four times the annual salary of the average working man), the winner to be named the ‘middleweight champion of Great Britain’. That fight would take place in December 1894. However, before then, Craig would fight 11 times in November 1894, including 4 exhibition fights on successive days (it has been suggested that two of these fights took place on the same day, 12 November) at the National Boxing Tournament at the Central Hall in Holborn, London. He won every one of the 11 contests, all but one by a KO. One occurrence of note with the Central Hall tournament was that Craig was poorly received by the crowd when he first appeared; although it was said that they warmed to him once he got down to work. Craig would form his own opinion as to the cause of the trouble, as I will detail below.[18]

In another of Craig’s appearances that month, and an event that is all the more interesting because of subsequent events, detailed below, Craig sparred with his manager, Denny Butler, on stage at the Eden Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue. The evening’s ‘entertainment’ ended with a ‘Battle Royal’ between 10 unidentified Black boxers. This, most distasteful of boxing ‘exhibitions’, a last-man-standing free-for-all with overtly racist overtones, was an unwelcome American innovation.[19]

However, the most significant event involving Craig and Butler in November was their parting of the ways, within days of the Eden Theatre event. At the time, it was claimed this was because Donovan had called Butler back to the States.[20] However, once Butler reached the US, the news came out that he was no longer Craig’s manager. In an interview with a New York journalist upon his return, Butler would characterise this falling out as a result of Craig’s refusal to follow Butler’s training regime because he had grown too fond of the high life that his newfound wealth and fame allowed him to lead.

Oh, his goings on are terrible! Why, he’s got enough neckties to fill a barrel, and he parades the Strand all day. Why, didn’t he pull a knife on me one day because I told him it wasn’t the real thing to wear his big diamond in his evening clothes, and it was also not right to appear in those kinds of clothes at 2 o’clock in the afternoon? Yes, indeed he did.[21]

Butler’s characterisation of Craig as having let fame go to his head was designedly playing to a stereotype of people of colour being unable to exercise self-control, a trope that went all the way back to apologists for slavery claiming that people of colour would be lost without white men to direct them, a position that gave birth to ‘plantation fiction’ and the myth of the ‘happy slave’.[22] We are justified in calling into question this account of events because it makes no mention of the man who replaced Butler as Craig’s manager: Ed Holske, the by-now former editor of the Mirror of Life.

Bostonian Edward Charles Holske (1857–1940), AKA ‘Ed’ or ‘Ned’ Holske, had been a champion competitive walker in the US back in the 1870s, in the heyday of pedestrianism. When interest in that sport waned, he switched to sports promotion and journalism. In 1887, he travelled to England with John L. Sullivan, the great bare-knuckle fighter, as his press agent. After the early death of his first wife the following year, he spent the next few years promoting and writing about various sports all over the world. He remarried in 1892 and, by 1894, as we have seen, he was back in England and serving as the editor of the Mirror of Life, an illustrated newspaper that featured boxing prominently in its pages.[23]

The idea of a boxer having a manager, commonplace today and already established in America by 1894, was, at the time, unknown in England. When Craig travelled to England with his American manager, Denny Butler, he was ignorant of this and readily accepted Butler’s explanation that to box in England, he would need to have an ‘English’ manager to work alongside Butler, and this manager would require an equal share of the purse. Step forward, Ed Holske, who, as we have already seen, had in reality already made a deal with Mike Donovan to this effect.[24]

It is clear, given subsequent events, that a some point, Holske put it to Craig that a two-way split was far better than a three-way split and presented himself as a better choice for Craig’s sole manager than Butler. It may well be that, in support of his argument, he asked of Craig a question that we ourselves might ask: how is it despite three successful years boxing in the US under Butler’s management, it was only after Craig travelled to England that he started to make real money? Regardless, Craig, who, as we will see below, had every reason to believe that he was not receiving his just desserts, albeit not for the reason he thought, was only too ready to agree. A break with Butler and Donovan was effected, and Ed Holske took sole control of Craig’s career and finances, with the result that we will see below.

That Butler left out from his account of his break with Craig that his role had been usurped by the man his mentor, Mike Donovan, had selected to support Butler in England, is not to be surprised: it was not in his interest to broadcast that he and Donovan had been duped; far better, from Butler’s point of view, to place the blame on Craig and cast him as the stereotypical man of colour lacking self control. This duplicity was to do Craig’s reputation lasting damage in the US.

"GREAT" GLOVE FIGHT Lasting Exactly 96 Seconds, or Less Than One Round. PRITCHARD v. CRAIG. The "Coffee Cooler" Knocks Out Pritchard Very Rapidly. A contest with four-ounce gloves, which excited a considerable amount of interest in sporting circles, took place evening at the Central Hall, Holborn.[25]

The long-planned Pritchard fight, with Holske now in sole charge of Craig’s career in England, took place at the Central Hall on Holborn on 17 December 1894. This time, Craig was well-received as he entered the ring and took his seat in his corner, chewing gum, as was his custom. The prediction was that the fight would go the distance; instead, it was all over inside two minutes. Although in theory a much tougher prospect than John O’Brien, Pritchard proved even more unable to cope with Craig’s power and intelligence as a boxer, falling again and again for Craig’s feints and quick changes of pace.

As the Englishman got upright to get out of danger, the Cooler promptly reached the chin with his left, and Pritchard, thinking the right was coming across, raised his guard higher, in order to protect the weak spot.” This was exactly what the Cooler had been playing for, and in an instant, he swung a half-arm uppercut, really a jab with his right. Pritchard went down though hit with an axe. He rolled over on to his side. Here he remained for a few seconds, and then got on to his hands and knees. Chesterfield Goode ran over to Pritchard and shouted, “Take your time.” Pritchard was oblivious to these instructions, as he was to the flight of the precious ten seconds. The sound of the gong rang out while he was still trying to assume that attitude which Mazeppa has almost deified. The timekeeper said that the bout had lasted but 1 min. 36 see. This is undoubtedly inclusive of the 10 sec. which was used while Pritchard was down.[26]

Craig was arguably the best middleweight boxer in England at this point, and the contest was billed as being for the ‘English middle-weight championship’—the title that Pritchard held going into the contest; however, it did not enter the record books as such for reasons I will outline below. Regardless, Craig was now at the peak of his career and fame.[27]

It will be remembered that the match with Pritchard was meant to be the culmination of Craig’s visit to Britain, and, in a letter to the British press in February 1895, Holske announced that Craig planned to return to the US in April ‘to fill several engagements’. However, this was not to be a permanent return to his country of birth; instead, Holske wrote, Craig intended to return to England afterward ‘to reside permanently’.[28]

In fact, as early as October 1894, Craig had told a journalist, ‘I am infatuated with Great Britain and propose to make this country my home.’[29] That much of Butler’s complaint about Britain turning his head was true. The country was no paradise for people of colour—it, after all, stood at the head of an empire sustained by the idea of white supremacy—but to Craig’s mind, and the minds of many other men and women of colour, it offered more opportunities to enterprising men of talent, whatever the colour of their skin, than Jim Crow America. Craig felt that acutely, even after only five months in the country.

Before returning to America, however briefly, Craig had one last order of business: a fight against Australian heavyweight Frank Slavin. This decision to, once more, go up a weight class, was to prove every bit as foolish as the fight against Peter Maher. However, to explain the background to the fight, we need to return to December 1894, the month that Craig defeated Pritchard.

PETER JACKSON AT THE CANTERBURY AND PARAGON. This (Friday) evening Peter Jackson will spar at both the Canterbury (Westminster Bndge-road) and the Paragon (Mile-End-road). At the Canterbury, the Coloured Champion of the World will be opposed by W. Grimes, well-known amateur, and proprietor of the Crown and Cushion, Westminster Bridge-road. Josh Cosnett, of Birmingham, will be Jackson’s opponent at the Paragon.[30]

Peter Jackson (1861–1901), one of the greatest heavyweight boxers of the bare-knuckle era, was a Black Australian who found fame in the US but was denied an opportunity to fight for the heavyweight championship of the world because John L. Sullivan, the holder, refused to to fight him, claiming that he would not fight a Black boxer, although his record suggested otherwise. Jackson found more success in England, gaining the Commonwealth heavyweight championship and becoming the most famous and successful boxer of colour in England of the bare-knuckle era.[31]

By December 1894, Jackson was past his prime and possibly already suffering from the tuberculosis that would kill him six years later. The middle of that month found him back in England, touring the English halls, putting on exhibition matches as entertainment. Craig, unquestionably by December 1894, the most famous and successful boxer of colour in England after Jackson, issued a challenge to Jackson via Holske a few days after the Pritchard fight.[32] This despite this meaning that, once again, he would be at a great weight disadvantage. He was clearly of the mind that you could only be considered the greatest by beating the greatest.

Jackson ignored the challenge. Instead, it was taken up by another Australian heavyweight boxer,[33] albeit a man of a very different temperament to Peter Jackson: Frank Slavin.

FRANK SLAVIN has a decided hatred [of] Peter Jackson and all coloured boxers. At the Central Hall last Saturday night, a lad was hawking THE MIRROR OF LIFE displaying the excellent full-page cut of Peter Jackson. When Slavin walked passed the lad, he caught a glimpse of the portrait of the coloured champion, and accepted the opportunity of jabbing the end of his walking-stick through the paper. He probably deemed it a clever trick, but a sensible person would pronounce it a miserable display of spite.[34]

Frank ‘Paddy’ Slavin (1862–1929) was a racist with a personal and professional hatred of Jackson, a man he had trained alongside and who had bested him in a 10-round contest for the Commonwealth title in London in 1892. He was keen for a rematch in December 1894 and saw his path to Jackson through Craig, perhaps believing that Jackson would only consider one contest, and it was, therefore, necessary to eliminate Craig from the competition. Along the way, Slavin could not resist a dig at Jackson’s race in a letter to the Sporting Life.

Whilst I have the greatest respect for members of [the National Sporting Club], I object to box there, for the sole reason that it appears to me that Jackson is the “colour” of their choice. London, March 12. FRANK SLAVIN.[35]

It is possible that Craig and Holske saw Slavin in the same light—an obstacle that blocked their path to a fight with Jackson that had to be cleared—or they may have seen him simply as a workout before the main event, a chance to show Craig’s mettle against a heavier fighter. Craig may have been influenced in this by the fact that in Minneapolis in June 1894, he had met and bested Paddy Slavin’s brother, Billy, with a second-round KO.[36] That they saw Paddy Slavin as no threat is clear, as was demonstrated by the confidence with which Craig approached what was to be the most lucrative—and most foolhardy—contest of his career to date.

Craig was attired in a dark coat, jersey, and trousers, and a light cap on his head. He sat unconcernedly chewing a wad of gum while patiently waiting the advent of his opponent.[37]

The bout took place at the Central Hall, Holborn, on 11 March 1895, in front of a crowd of 6000. The crowd greeted both boxers enthusiastically on their entrance—the Sporting Life in its reporting was keen to point out that the assembled fans bore Craig no personal ill-will, for reasons which we will see. Craig had bulked up for the fight but was still around 14 pounds lighter than the Australian, who was also taller and had a longer reach. Both men had trained hard in the weeks before, but Slavin had not fought for over a year, while Craig was the man of the moment, so the betting, though close, was in Craig’s favour, with odds of 5–4 and 6–4 being offered.[38] The two men squared off against each other. The bell rang to mark the start of the fight. Seventy seconds later, it was all over.

The men then got very close, and just as they looked like indulging in a bit of infighting, Slavin shot his right up under his opponent’s jaw, and Craig, as if shot, swung round and fell with crushing force on the boards, where he lay face downwards. Few present could realise what had happened, and many never saw the blow that caused such an astonishing result.[39]

The crowd erupted in celebration. And it was now that the Sporting Life gave voice to the feelings of many of those assembled; keen to point out before the fight that no one present bore Craig any personal ill-will, after it was all over, it was just as keen to point out, in the language of the time, how satisfying it was for many of those present to see a Black fighter at last defeated by a white one.

From time immemorial, men of colour have proved themselves singularly apt with their fists, and many well-fought field gladiators of dusky hue have given end of trouble to the ablest exponents of the art of self-defence. [..] the modern darkies have done even hotter than their predecessors, for while the Ethiopian warriors mentioned did nothing better than furnish striking instances of the superior skill and stamina of the white man, it remained for Peter Jackson and George Dixon to tear the laurels from the brows of their palefaced opponents in fair fight, and upset all traditions proving their right to dubbed champions. Other coloured men have endeavoured to emulate the example set by the pair referred to, and if the white trash don’t bestir themselves, it requires no very wide stretch of the imagination to picture the whole batch of championships from bantamweights to heavies in the possession of the descendants of Ham at no distant date. Hence the popularity of Slavin’s victory last night.[40]

The term ‘the Great White Hope’ was not coined until after Jack Johnson became the first Black heavyweight champion of the world in 1908;[41] however, the outpouring of schadenfreude that followed Frank Craig’s defeat at the hands of Paddy Slavin in 1895 showed that the feeling of the affront to white supremacy of having boxers of colour best white men in the ring was of far older origin.

Craig tried to shrug off the defeat, telling the Sporting Life a few days later, ‘I’ll admit that Slavin is a taller and heavier man than myself, but that don’t convince me he is my superior.’ He hoped for a rematch, but before that, he had to deal with Ted Pritchard, who disputed Craig’s right to call himself middleweight champion, claiming to still hold the title himself, requiring a rematch in that direction.[42]

Gone was any suggestion of a trip back to the US to challenge the best of the fighters there. Despite his big talk, Craig’s defeat at the hands of yet another heavier boxer had dealt his career a blow. That was certainly the view on the other side of the Atlantic.

SAM AUSTIN, of New York, says :—"I never heard of a pugilist dropping so quickly in the estimation of the matchmakers as Frank Craig, the Harlem Coffee Cooler. A month ago, had he returned to America, he might have named the size of the purse and picked out his own opponent, but that defeat by Slavin brought about by a chance blow (perhaps), has caused a reversal of opinion regarding his fistic ability, and now I don't know of a club here that would give a purse to have him as an attraction."[43]

Craig’s career was to receive two more blows in the months following the Slavin fight. First, the Pritchard rematch turned into a farce: Pritchard bowed out after developing a severe chill, and John O’Brien was brought in as a last-minute replacement; so last-minute that he had to be brought from the pub where he had been enjoying a drink for the contest; he was so unfit to box that he retired after only one round to the uproar of the crowd.[44] It was in the aftermath of the O’Brien fight, which, if Pritchard had boxed, would have been for a purse of £500, that Craig was to discover something shocking about his finances and his manager Ed Holske.

THE COFFEE COOLER'S STATEMENT. My first fight in England was with Johnny O'Brien. The money was divided equally between Mr. E. C. Holske, Denny Butler, and myself, and was satisfactory to me. In the Pritchard fight, I was entitled to £230, and Mr. Holske to £120. I got only £70. At the Slavin fight, the total gate receipts, as represented to me, were £1200, out of which Frank Hinde got 30 per cent:—£360: Charley Mitchell 35 per cent:—£420; E. C. Holske 35 per cent:—£420. Holske was entitled to a third of the £420, and I to the balance. I only got £171, instead of £290. From the second O'Brien fight, I received £6 nett, Mr. having deducted his third share, so that, presumably, the total received was £9.[45]

It was a tale as old as time: an artist or athlete fleeced by their manager. Holske had even gone so far as to ignore the tradition of standing rounds at the bar before a fight to win over the crowd—the source, Craig believed, of the ire they had borne him at the National Tournament. The pitiful return from what was admittedly a pitiful fight, the second O’Brien contest, seems to have finally woken Craig up to the fact that Holske was keeping most of his earnings from himself. By the same token, the blatant fraud involved in paying Craig only £6 for the contest was a clear indication that Holske saw that Craig’s career was now at such a low ebb that there was nothing more to be gained from continuing to ride his coat-tails: he took his ill-gotten and ran back to the United States and his home town of Boston, where he went into the grocery business.[46]

The timing could not have been worse for Craig: one of Holske’s last jobs before fleeing was to secure Craig’s big comeback fight, against another Australian, albeit a middleweight, Dan Creedon. Creedon had already bested Craig twice in the US, but, as this was to be a contest for the middleweight championship of Great Britain and Craig’s career and bank balance were both at a low ebb, it was a chance he had to take.[47] Losing his manager and having to take on all the arrangements for finding a training venue and hiring sparring partners for himself on top of signing contracts was a distraction he did not need.

A brilliant assemblage of the members and their friends attended bead-quarters last night when the first of the series of International glove contests arranged by the executive of the National Sporting Club, for decision at intervals during the season, was brought to a successful issue. It was the long-looked-forward-to battle between the Yankee coloured man, Frank Craig (better known as the “Coffee Cooler”), and Dan Creedon, of Australia, that attracted the fashionable crowd.[48]

Craig and Creedon took to the ring at the National Sporting Club on 14 October 1895. Both men were in excellent condition, and the fight did not disappoint, going the distance with the advantage passing from one man to the other and back again across 20 bruising rounds. In the end, it was Creedon’s superior stamina that told, with a tiring Craig getting the worst of the fight in the final rounds. Creedon was declared the winner.[49]

After this disappointment, Craig would not box competitively for another 8 months. This is not to say that he put boxing aside; rather, his fights were exhibition matches on the theatre stage, not in the ring, as, for the moment, Craig turned his attention to growing his second career, that of a star of the Music Hall.

Frank Craig, the Coffee Cooler, was introduced. The conqueror of Johnny O’Brien met with a big reception, but this time, however, the coloured boxer appeared in the ring to display his skill in another direction. Armed with a mouth organ, Craig played a selection of airs, and wound up by executing in capital style, a buck dance, playing the said mouth organ all the while. He displayed remarkable activity, and many of the steps were not only original but exceedingly difficult, and on quitting the platform, he received a hearty round of applause.[50]

Telling the story of Frank Craig’s career as a star of the Music Hall, which was to provide him with a regular income at the height of his fame as a boxer in 1894/95 and long afterwards, requires an examination of Britain’s unfortunately long affair with blackface minstrelsy, which I have done elsewhere.[51] Suffice to say here, from the 1840s onwards, white performers of blackface minstrelsy, the caricaturing of African Americans, were a popular draw on the English stage, a process propelled, paradoxically, by the huge success of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which received its first publication in England in 1858. With the end of the American Civil War and the emancipation of enslaved Africans, Black performers of blackface minstrelsy began to appear in large numbers, which led to the birth of the so-called ‘Tom Shows’ in the US, strange theatrical entertainments that married dramatic retellings of the Stowe novel with ‘plantation interludes’, song and dance extravaganzas that featured genuine performers of colour take the stage in the roles of ‘happy slaves’, singing and dancing on the plantation under the benevelant gaze of their kindly white masters—the myths spun by plantation fiction brought to sorry life.

The first Tom Shows transferred to England to huge success in the 1870s, and from that time until the end of the century, a number of producers toured their own versions of Tom Shows up and down the country. While never rising above racist caricature, at the same time, Tom Shows provided employment for a large number of genuine performers of colour—some of whom even went on to lead their own theatrical companies and stage their own Tom Shows. They also brought to the attention of English audiences styles of music and dance innovated by African American communities across the US, buck dancing prime among them.[52]

All of which is to say that the audiences that saw Craig perform would recognise in his performance acts that they had seen in minstrel and Tom shows, to the extent that Craig’s style of dancing was routinely referred to in the press as a ‘plantation dance’.[53] This was giving white audiences what they expected: a caricature of African American life. However, the money that Craig earned performing on the stage, particularly at the height of his fame, gave him a luxury few other boxers could afford: to pick his fights. As the music and dance performance, at least in the early days, was accompanied by sparring contests against local amateurs or Craig’s associates (Denny Butler in November 1894; after this time, African American boxer Jack Lewis, who joined Craig’s camp at the time of the second O’Brien fight), these tours also kept him fit.[54]

As time passed, particularly after the downturn in Craig’s boxing career following the events of the spring and summer of 1895, Craig’s act would evolve from a solo musical and dance performance alongside a boxing exhibition into a fully fledged Music Hall turn with a company of fellow African American performers that he led recruited from the many such performers touring the halls with the Tom shows. Chief among Craig’s collaborators were Robert Cropp, James Johnson, and Jasper ‘Dusty’ White. Cropp, who became Craig’s business manager, was a ‘sentimental and comic vocalist’; he and Johnson specialised in female impersonation, a prominent feature of minstrel shows of the period. White was a comedian and boxer who sparred with Craig to sometimes serious, sometimes comic effect.[55]

Craig’s involvement in the theatrical world had an interesting side effect: it resulted in his becoming briefly involved with attempts to introduce American baseball into Britain. The London Baseball Association (LBA), one front in this ultimately unsuccessful campaign, was populated mainly with American and Canadian music hall artists, songwriters, and journalists. In the Summer of 1896, Craig played at least two games for the team sponsored by whisky magnate Thomas Dewar. The team manager that season was Canadian-born Music Hall star R.G. Knowles, the founder of the LBA. The Dewars team included at least one other player of colour in the person of ‘Carey’, a three-year veteran of the LBA. Known only by that name, evidence suggests that he was Charles Carey, an African American Music Hall performer who was, alas, to die an early death. Coincidentally, by the time that Robert Cropp joined Craig’s theatrical company, he had also taken part in efforts to introduce American baseball to the Manchester region. Carey and Cropp’s skill in the sport arose from the common practice of minstrel troupes in the US to use baseball as a promotional activity, touring the country and challenging local teams to games to gain publicity for their performances in local theatres.[56]

It was also in the period following the fight with Creedon and Craig’s next competitive fight, 8 months later, that Craig got married, to seamstress Louisa Sarah Shannon. Louisa lived near Brighton, and the couple started to live together there as man and wife in the summer of 1895; however, they only made things legal in January 1896, by which time, Louisa was pregnant with what would prove to be their only child, Frank Walter Shannon Craig Jr. Born on 26 July 1896, Frank Jr would become a casualty of the First World War, killed in action at the Battle of Delville Wood, two days after his 20th birthday, while serving with the 8th Rifle Brigade.[57]

By 1901, Frank and Louisa were running the Three Tuns Hotel in Brighton, which became a place to rest and train for African American boxers visiting Britain. It is not unreasonable to suppose that Craig bought the business soon after his marriage and left it to Louisa to run while he toured the halls, giving his wife and child a settled existence and regular income.[58]

It is worth noting here that in the early 1930s, two young boxers of colour would emerge who would be billed as Frank Craig’s sons, a second Frank Craig Jr and a Charles Craig. At least one of these boxers—who appeared to have had no connection—would have someone identified in the press as his father, Frank Craig, the Coffee Cooler, acting for him. There is nothing to indicate that Frank Craig had more children after the first Frank Craig Jr, and even if he did, it seems highly unlikely that he would give two of his children the same name (based on the age of the second ‘Frank Jr’ in 1932, he would have been born in 1911, at which time, the ‘first’ Frank Jr was very much still alive). The more likely explanation is that these were simply two young boxers of colour trading on the Craig name. If the real Frank Craig did appear as a second for either or both of these young boxers—and this is by no means certain—it was likely that this was purely a financial arrangement and nothing to do with any familial connection. However, it must be acknowledged that there is much about this affair that remains mysterious. We do know that the real Frank Craig did train young boxers, particularly boxers of colour, in his later years, as detailed below.[59]

When least expected, Craig got home a clip on the point of the jaw, which felled the Colonial, who was unable to rise within the allotted ten seconds. The referee declared Craig the winner when only a similar number of seconds remained to the end of the round. Both winner and loser were heartily cheered at the close of their stubborn and much-appreciated battle.[60]

Craig’s return to the ring in May 1896 was marked by a victory by a KO in the tenth round against Australian middleweight Tom Duggan. However, the contest at the National Sporting Club drew only a small crowd. It would be more than a year before Craig boxed competitively again—a measure of both that he was no longer the attraction he had once been, on the one hand, and that he could earn more touring the halls, on the other. His defeat at the hands of American Dick O’Brien in October 1897 would trigger another year-long drought, but this would be followed by two fights in quick succession, both title fights and both victories for Craig.

The first, in London, against Australian Billy Edwards, was a woeful affair in which Craig went on the offensive right from the first bell only to be stymied time and time again by Edwards going for the clinch. It took Craig 12 disappointing rounds to break free long enough to deliver a KO punch, but it at least left him the holder of the English open middleweight championship. The second, a month later, in Newcastle Upon Tyne, against local boxer George Chrisp, finally delivered to Craig the accolade he had in truth possessed since his victory against Ted Pritchard back in December 1894: middleweight champion of Great Britain. The fight again went to 12 rounds, but these were 12 furious rounds with Chrisp giving as good as he got in the early part of the contest.[61]

Within a week, Craig was back on the halls, touring with his musical comedy company (which at the time had the unfortunate name of ‘Frank Craig and his Piccaninnies’[62]). He would not fight competitively again for nearly another year. And when he did, it would be in America.

One of the many important matches fixed by Mr. W. A, Brady on behalf of the Coney Island A.C. of New York during his recent visit to this country was that between Tommy Ryan (of Syracuse) and Frank Craig (the “Coffee Cooler”). A copy of the articles agreement recently appeared in these columns, and Saturday last, the coloured middle-weight, and conqueror of Johnny O’Brien, Ted Pritchard, Tom Duggan, George Chrisp, and Billy Edwards, left this country to fulfil his portion of the contract.[63]

William A. Brady (1863–1950), as colourful a character as ever got involved in boxing, was the architect of the career of Gentleman Jim Corbett, the first heavyweight champion of the world of the post-bare-knuckle era. In 1897, Brady leased the Coney Island Athletic Club with a view to staging boxing matches there, and in the summer of 1899, travelled to England to sign up the best of the fighters on this side of the Atlantic to take back to the States with him.[64]

The £700 purse that Brady was offering, along with the chance to return to the US as champion, proved too tempting for Craig to resist. He and his business manager, Robert Cropp, set sail in late August 1899. Alas, if Craig was hoping to be greeted as a returning hero, he was in for a rude awakening. Resented for having chosen England over the land of the free, which wasn’t helped by his joking that he now had a ‘cockney accent’, Craig went into his contest with Tommy Ryan not only heavily unfavoured but also facing a crowd that was willing him to lose. He gave it his all, but for once found himself facing a cleverer boxer. Ryan wore Craig down over 10 grueling rounds, constantly getting the better of the increasingly weary Craig. After Craig went down again in the tenth, he beat the count but was so clearly done in that the referee stopped the fight.[65]

Things then went from bad to worse for Craig: his brother, acting on his behalf, had arranged two more fights for him while he was in America, in Chicago and New York. The Chicago fight turned into two fights, a few days apart, against the same opponent, Jim Root, after Craig lost the first on points and complained that this was based on a rule (breaking clear) that he had not agreed to; he also lost the rematch. In his final fight, in New York, against Tommy West, he was floored sixteen times across 14 rounds before the referee stopped the fight. Craig returned to England a humbled man.[66]

THE “COFFEE COOLER” DISQUALIFIED. At Wonderland, Whitechapel, last night, Frank Craig, the “Coffee Cooler” boxed George Gardiner, of Ireland, for a purse of £200. They were to have boxed 20 rounds, but Craig was disqualified by the referee in the fifth round for deliberately throwing his man, and Gardiner was returned the winner.[67]

Frank Craig would continue boxing for another 40 years, but his time in the top flight was over. For the first few years following his return from his disastrous American trip, he continued to have good match-ups, including chances at championship belts, but met with defeat every time. He would only rediscover his winning ways when he bowed to the inevitable and started to box men who were largely without talent.

In common with many former top-flight boxers, by the middle of the first decade of the new century, Craig’s only real sources of income were outside the ring: his hotel/pub in Brighton and his appearances on the Music hall stage. However, again, in common with many other former top-flight boxers,[68] Craig lost most of his money. Evidence suggests that the hotel was gone by the start of the 1910s: the 1911 England Census saw Craig living in Marylebone while Louisa and Frank Jr were still in Brighton, but no longer at the Three Tuns; instead, Louisa was working as a milliner. In his 1915 declaration to the US Consulate, Craig described himself as a former boxer working in the dressmaking trade and living with his wife, Louisa, in London, while their son continued to live in Brighton. The marriage appears to have ended not long after the tragic death of their son, killed in action in 1916—by 1939, Craig would be describing himself as a ‘widower’.[69]

In 1912, Craig found himself caught up in a murder plot after he purchased a gun on behalf of a fellow African American Music Hall performer, Annie Gross, that Gross used to shoot to death her husband’s lover, actress Jessie ‘Tricks’ MacKintosh. Craig was initially charged as an accessory before the fact, only to be discharged after no evidence could be produced to suggest that he knew what Gross intended to do with the weapon. Annie Gross’s story was a tragic one: forced into prostitution by a brutal husband who used her earnings to set up a new home with his lover. She received five years for manslaughter.[70]

Although a tragic case for all concerned, the Gross affair was indicative of how, after living in Britain for nearly 20 years, Craig had become a point of contact in England, particularly London, for African American visitors to the country. We have already seen how back in the days when he was running the Three Tuns Hotel in Brighton, it became somewhere to rest and train for African American fighters booked to box in London. Alas, as with the Gross affair, most of the other evidence we have for Craig’s standing in the African American community in London comes from brushes with the law. This is most obvious in the events of April 1919, when Craig’s home in Bloomsbury was raided by the police after reports that it was being used as a gambling den. Inside, the police found a dozen or so ‘jazz musicians’ drinking and gambling. Craig was arrested; however, the story that emerged at his trial was one of African American musicians performing in London, having tried unsuccessfully to establish a club for visiting African American artistes for want of a venue that would allow them entry, accepting an offer from Craig to meet at his home instead.[71] (This is not to suggest that Craig’s motives were purely altruistic: he charged the men for their drinks.)

Craig would also, increasingly, train and act as a second for other boxers, particularly other boxers of colour. The most prominent of these would be Leone Jacovacci (1902–1983). Jacovacci’s story was an incredible one: of African-Italian heritage, he served in the British Army under the name ‘John Douglas Walker’, fought in London under the name ‘Jack Walker’ under Craig’s tutelage, and, in 1928 in Italy, under his own name, won the European middleweight championship, defeating a white boxer before an audience of 40,000 that included Benito Mussolini and other leaders of Italian fascism. To appease the regime’s displeasure at the victory of a mixed-race man over a ‘pure’ Italian, Jacovacci joined the Fascist Party, but it was to no avail, and he fled to France to escape further persecution. He was living in France with his partner, Berthe Salmon, when the Germans invaded in 1940. Unable to escape, he and Berthe, who changed her surname to Roquet to hide her Jewish identity, endured 4 years of Nazi rule. On France’s liberation, Jacovacci rejoined the British Army for the duration. He lived out the final years of his life in relative obscurity and poverty in Italy. Following his European championship victory, Jacovacci told the press that he learned everything he knew about boxing from Craig.[72]

Craig’s final years were not happy ones. The year 1937 found him, aged 69, taking on all-comers at a boxing booth in London at £5 a bout. This was also the year he went to prison for two months for striking a woman, his partner, over the head with a bottle. By 1939, he was an inmate in the Fulham Road Institution, Chelsea, a former workhouse turned hospital for the ‘chronically sick and aged’, his occupation given as ‘actor, incapacitated’, pointing to serious infirmity. He died at St. Stephen’s Hospital, Chelsea, in December 1942, of cerebral thrombosis. At the time, he was homeless. On his death certificate, under the heading ‘rank or profession’, was written, simply, ‘formerly a boxer’.[73]

* * * ON September 28, McHugh, Pony Moore, Stanbrook, and Lester, accompanied THE MIRROR OF LIFE representative on a trip to Eltham to call on Frank Craig, the Coffee Cooler. […] He looked in the pink of condition, and after a brief conversation with the visitors, he ushered them into his gymnasium, where he indulged in a spirited bout with his friend and adviser Denny Butler. The form he displayed was greatly admired by all present, and when he went through his exercise with the punching ball, the entire party, to a man, freely declared that he was a most remarkable fellow, and good enough to cope with any middle-weight in the world.[74]

Frank Craig was not perfect; in fact, arguably, he was highly flawed: He made bad decisions as to management and opponents, and was not wise with money. However, in this, he was no different from many other boxers, men raised in poverty suddenly thrust into the limelight, their pockets stuffed with cash. More seriously, he, at least in his old age, treated women badly. Alas, in this, he was also no different from many other boxers, but his behavior should not be excused because of this. He was a man with flaws.

The early death of his only son and the later separation from or loss of his wife left him without support in his infirmity, and he died alone, remembered only as ‘formerly a boxer’. That was his tragedy. And it was a tragedy, as he lit up the British boxing scene in 1894 when he arrived from America. In his first two years in the country, his ill-advised contest with Paddy Slavin notwithstanding, he moved the sport in Britain forward a decade, schooling dozens of boxers and their trainers, and thousands of spectators, in the fast-paced, two-fisted American style. His second career, on the stage, the income from which allowed him to pick his opponents (although not always wisely), saved him from the only too common fate of boxers: an early death or long, ‘punchdrunk’ decline due to the need to keep chasing purses. Thanks to this, in later life, his wits still about him, he was able to become a mentor for younger boxers, particularly younger boxers of colour, Leone Jacovacci prime among them. He deserves to be remembered for that, if nothing else.

Jamie Barras, September 2025.

Back to The Spectacle

Notes

[1] Theory that Black people ‘do not feel pain to the same measure as white men’ giving Black boxers an ‘unfair advantage’: ‘When Black Meets White: the Ring Memories of ‘Gene Corri’, Sunday Pictorial, 29 January 1933. I should point out that Gene Corri, a famous boxing referee, was not someone who believed in this idea; he merely mentioned it in this article as something that some people believed. For Craig’s defeats being celebrated: see discussion of the 1895 Slavin–Craig fight in the text and associated endnotes below. Craig taken to task in the African American Press: ‘The Lion of the Hour’, Freeman (Indianapolis, Ind.), 9 February 1895. It has to be acknowledged that the latter was reacting to an account of Craig’s excesses provided by his embittered former manager, ‘Professor’ Denny Butler.

[2] ‘Our Colored Champions’, The Sun (New York, NY), 21 November 1890.

[3] Story about 1870 date for Craig’s birth and boxing since age 14: ‘International Glove Contest at the Central Hall Holborn: Performances of the Men–Frank Craig’, Sporting Life, 12 March 1895. Story about ‘Red Indian mother and Cuban negro [father]’: See Note 1 above, first reference. Official records with 1 April 1868 and New York, date and place of birth: Frank Walter Craig, 23 June 1915, London, U.S., Consular Registration Certificates, 1907–1918; father Luke Craig, miller: entry for Frank Walter Craig, 7 January 1896, Saint Mary, Stoke Newington, Parish Register, London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1940, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 10 September 2025.

[4] Chris Benedict, ‘Frank Craig ‘“The Harlem Coffee Cooler”: Do You Take Your Boxing Legends With One Lump or Two?’, Ringside Report, https://ringsidereport.com/?p=54533, accessed 20 September 2025. Craig coining the name himself and the McCormick version: See Note 1 above, final reference. Lunch counter version: ‘The Coffee Cooler’, Birmingham Age-Herald (Birmingham, Ala.), 12 April 1920.

[5] ‘The Coffee Cooler’, Monmouth inquirer (Freehold, N.J.), 1 February, 1883. ‘A Reporter of the Louisville Courier-Journal..’, Weekly Messenger (St. Martinville, La.), 4 June, 1887.

[6] I have to admit that, although, Craig frequently boxed at the New Yok Athletic Club and Lenox Lyceum on fight cards organised by Butler and Donovan (see Note 7 below), the earliest reference I have found to Butler being Craig’s ‘backer and trainer’ is from 1894; however, in that article, Butler is described as having trained Craig for the past three years: ‘The “Coffee Cooler”’, Saint Paul Daily Globe (Saint Paul, MN), 8 June 1894.

[7] Butler bio: ‘mcsheam’, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/205340029/dennis-f-butler; Donovan bio: Paul Zanon, ‘The Professor’, https://www.britishvintageboxing.com/blogs/news/the-professor?srsltid=AfmBOorrroeSJQ4ArmsjPuDqUOC3NxSXZPZ0diVRLk6Vuz7xZjrK7eL2, accessed 20 September 2025. Craig on N.Y.A.C. and Lenox Lyceum fight bills: ‘Boxing at the N.Y.A.C.’, New-York Tribune, 27 November 1892; ‘Sporting News and Gossip’, Evening World (New York, NY), 13 February 1894. Donovan benefit: ‘Meetings and Entertainments’, New-York Tribune, 6 April 1892.

[8] Craig’s boxing record: https://boxrec.com/en/box-pro/39932?&offset=100, accessed 20 September 2025.

[9] ‘Frank Craig, the Coffee Cooler’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 8 September 1894.

[10] Donaldson making the deal: ‘Around the Ring’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 4 August 1894. Trip first mooted back in the Spring: ‘Boxing Items’, South Wales Echo, 31 March 1894.

[11] Craig and Butler’s arrival: entry for Frank Craig and D.F. Butler, passenger lists, Mohawk, arriving London, 12 September 1894, UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists 1878–1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 10 September 2025.

[12] Sarah E. Cox’s Grappling wth History website is an excellent resource on Black boxers in Britain in the bare-knuckle era: https://grapplingwithhistory.com/, accessed 21 September 2025.

[13] Briggs Seekens, ‘The Transition from Bare Knuckles to Gloves’, https://medium.com/pioneers-of-boxing/the-transition-from-bare-knuckles-to-gloves-969d6754eb55, accessed 21 September 2025.

[14] ‘International Glove Contest at the National Sporting Club’, Sporting Life, 9 October 1894.

[15] See Note 14 above.

[16] ‘The “Coffee Cooler” in Wales’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 10 November 1894.

[17] Neil Carter, “British Boxing’s Colour Bar, 1911-48,” n.d., https://www.academia.edu/3190661/British_Boxing_s_Colour_Bar_1911_48, accessed 21 September 2025.

[18] ‘Frank Craig to Ted Pritchard’, Sporting Life, 9 October 1894. For Craig’s record in England, see Note 8 above. Craig at the Natonal Boxing Tournament, November 1894 (he was scheduled to box on every day of the weeklong tournament): ‘Boxing Tournament’, Manchester Courier, 12 November 1894. Unfriendly crowd: ‘International Boxing Contest’, Sporting Life, 18 December 1894.

[19] ‘Boxing at the Eden’, Morning Leader, 17 November 1894.

[20] ‘Round the Ring’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 17 November 1894.

[21] See Note 1 above, final reference.

[22] Robert Bryan Hawks, "Boxing Men: Ideas Of Race, Masculinity, And Nationalism" (2016). Electronic

Theses and Dissertations. 1162.https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1162.

[23] Edward C. Holske, competitive walker: ‘Current Mention’, Independent Statesman (Concord, N.H.), 13 May 1880; same man as Craig’s manager: ‘Stage Gossip’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 20 April 1895. John L. Sullivan’s press agent:’Fighting for Glory’, Sporting Life, 14 August 1888. Career as sports promoter and journalist: ‘An Editor and a Shooter’, Cheyenne Daily Leader (Cheyenne, Wyo.), 6 October 1889. Biographical details: https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/details/9ZMM-HQX, accessed 23 September 2025. That ‘Charles Edward Holske’ and ‘Edward Charles Holske’ were the same man can be confirmed from their residence (Boston) and the name (Annie) and year of death (1888) of the first wife of both men: ‘Has Sinned Enough: Ed C. Holske Decides Not to Figure in Future in Prize Ring Contests’, St Paul Daily Globe (St Paul, Minn.), 21 September 1888.

[24] This account of the role of the manager in US versus England and how Holske became Craig’s second manager is taken from Craig’s own account given after he and Holske had parted ways; however, it is supported by later reporting of the affair, which at the very least shows that Craig’s version was believed. Craig’s account ‘The Coffee Cooler’s Shout’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 18 August 1895; later support: ‘Mysterious Billy Smith’, Illustrated Police Budget, 21 March 1896.

[25] ‘“Great” Glove Contest’, Evening News (London), 18 December 1894.

[26] ‘International Boxing Contest: The Fight’, Sporting Life, 18 December 1894.

[27] ‘Glove Contest in London: The English Middle-Weight Championship’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 18 December 1894. In advertising in advance of contest, it was billed as ‘The Great Match for the Middle-Weight Championship’: ‘Central Hall Holborn’, Sporting Life, 14 December 1894. The entry for the fight at boxrec is unfortunately incorrect, claiming it was a three-round contest at ‘Holloway Road Baths’ (see Note 8 above).

[28] ‘Frank Craig and his Challengers’, Sporting Life, 5 February 1895.

[29] See Note 16 above.

[30] ‘“Great” Glove Contest’, Evening News (London), 18 December 1894.

[31] https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/jackson-peter-6814, accessed 22 September 2025.

[32] ‘The “Coffee Cooler” Challenges Peter Jackson’, Sheffield Evening Telegraph, 22 December 1894.

[33] ‘Frank Slavin to Frank Craig’, Sporting Life, 27 December 1894.

[34] See Note 20 above.

[35] ‘Frank Slavin and Peter Jackson’, Sporting Life, 14 March 1895.

[36] ‘Prize-Fight in America’, Echo (London), 12 June 1894.

[37] ‘International Glove Contest at the Central Hall Holborn: Scene at the Rendezvous’, Sporting Life, 12 March 1895.

[38] See Note 37 above.

[39] ‘International Glove Contest at the Central Hall Holborn: Scene at the Rendezvous’, Sporting Life, 12 March 1895.

[40] ‘International Glove Contest at the Central Hall Holborn’, Sporting Life, 12 March 1895.

[41] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/great%20white%20hope, accessed 23 September 2025.

[42] ‘Boxing: Frank Craig at the “Sporting Life” Office’, Sporting Life, 14 March 1895.

[43] ‘Round the Ring’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 20 April 1895.

[44] ‘Boxing. Central Hall, Holborn: A Pitiful Exhibition’, Sporting Life, 14 March 1895; ‘Our Opinion: Who Killed Cock Robin?’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 20 April 1895.

[45] See Note 24 above, first reference.

[46] See Note 23, fifth reference, and: Things Not Generally Known’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 21 September 1895. It is worth pointing out here thatHolske was suspected of dishonesty while promoting fights in the US, a circumstanc that led to his first wife horsewhipping a journalist who committed the allegations to print: ‘Whipped by Mrs. Holske’, Evening World (New York, NY), 24 October 1887.

[47] ‘Dan Creedon: Australia’s Great Middle-Weight’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 21 September 1895.

[48] ‘International Glove Contest at the National Sporting Club’, Sporting Life, 15 October 1895.

[49] ‘International Glove Contest at the National Sporting Club: the Contest’, Sporting Life, 15 October 1895.

[50] ‘Glove Contest at the National Sporting Club’, Sporting Life, 16 October 1894.

[51] My Cuckoos and Nightingales series: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities, accessed 23 September 2025. For an academic treatment, see: David Taylor, ‘From Mummers to Madness’, Chapter 12 ‘The Minstrels Parade: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Music Halls’, University of Huddersfield Press, 2021. Available to download here: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/50575, accessed 23 September 2025.

[52] Tom Shows: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-cuckoos-and-nightingales; buck dancing: https://www.ncpedia.org/buck-dancing, accessed 23 September 2025.

[53] ‘Round the Ring’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 24 November 1894.

[54] For Jack Lewis, see Note 44 above.

[55] ‘The “Coffee Cooler” at Newport’, Star of Gwent, 11 August 1899; ‘Variety Theatres’, Manchester Evening Chronicle, 20 June 1899.

[56] Craig in the Dewars team: ‘Baseball’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 26 June 1896. I tell the story of the LBA, Craig, Carey, and Cropp and American baseball in Britain here: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-behind-the-mask. For the story of Charles Carey’s life, see: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-messrs-broom-and-carey, accessed 23 September 2025.

[57] Craig and Louisa Shannon living as man and wife: ‘Lively American Topics’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 31 August 1895. Marriage: See Note 3 above, fourth reference. Birthdate of Frank Jr: See Note 3 above, third reference. Date and circumstances of Frank Jr’s death: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/275895713/frank-walter_shannon-craig, accessed 23 September 2025. Eighth Rifle Brigade, July 1916: https://www.wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/allied/battalion.php?pid=6869, accessed 23 September 2025.

[58] Entry for Frank and Louisa Craig, Brighton district, 1901 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 10 September 2025. Joe Walcott staying at the Three Tuns before his contest against Tommy West ‘World Welterweight Championship’, Sporting Life, 23 June 1902.

[59] 21-year-old ‘Frank Craig’ claiming to be son of the Frank Craig: ‘Wants Opponents: Coloured Boxer’s Challenge to Lightweights’, Nottingham Journal, 12 February 1932; Charles Craig seconded by ‘his father Frank Craig, the old Harlem Coffee Cooler’: ‘Boxing at Bury’, Bury Free Press, 15 January 1938; Craig training young fighters: ‘Sportsman’s Log’, Leicester Evening Mail, 21 November 1933.

[60] ‘International Glove Contest’, Illustrated Police Budget, 16 May 1896.

[61] Craig and Edwards: ‘National Sporting Club: Frank Craig and Billy Edwards’, Illustrated Police Budget, 22 October 1898; ‘Boxing’ Pall Mall Gazette, 18 October 1898. Craig and Chrisp: ‘Late Boxing: Great Gloves Contest at Newcastle’, Sporting Life, 26 November 1898.

[62] ‘Birmingham: Empire Palace’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 2 December 1898.

[63] ‘Frank Craig v Tommy Ryan for £700’, Sporting Life, 30 August 1899.

[64] https://www.heartofconeyisland.com/brady-coney-island-athletic-club.html, accessed 23 September 2025.

[65] ‘Tommy Ryan Defeats Frank Craig’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 4 October 1899.

[66] Two Chicago fights: See Note 8 above and: ‘Fistic Event’, Guthrie Daily Leader (Guthrie, OK), 7 October 1899. New York fight: ‘Boxing in America’, Morning Leader, 27 November 1899.

[67] ‘The “Coffee Cooler” Disqualifed’, Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette, 11 September 1900.

[68] ‘Boxers as Financiers’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 3 June 1922.

[69] Entry for Louisa Craig, Brighton district, 1911 England Census, entry for Frank Craig, Marylebone district, 1911 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 10 September 2025. 1915 consular registration: See Note 3 above, third reference. ‘Widower’: entry for Frank Craig, Chelsea district, 1939 England and Wales Register, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 10 September 2025.

[70] ‘Clerkenwell Murder Charge’, Belfast News-Letter, 19 December 1912; ‘Boarding House Tragedy’, Cork Weekly Examiner, 18 January 1913.

[71] ‘“Jazz” Band Raided’, Daily Express, 10 April 1919.

[72] Craig in Peter Pan at age 60: ‘“Coffee Cooler”’s Birthday’, Weekly Dspatch (London), 25 January 1925. Craig and Jacovacci/Walker: ‘Mike Blake Takes Revenge’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 19 Febuary 1921; ‘“Walker” Jaccovacci’, Sunday Express, 12 August 1928. Jacovacci’s story: https://www.europeana.eu/en/stories/leone-jacovacci-the-afro-italian-boxer-who-faced-fascism, accessed 24 September 2025.

[73] 1937 troubles: ‘73, Still Boxes Anyone’, Daily Mirror, 12 October 1937. Address in 1939: see Note 69 above, final reference. Circumstances of death: Death certificate, Frank Craig, registered 18 January 1943, digital copy obtained from General Register Office, September 2025.

[74] ‘Round the Ring’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 6 October 1894.

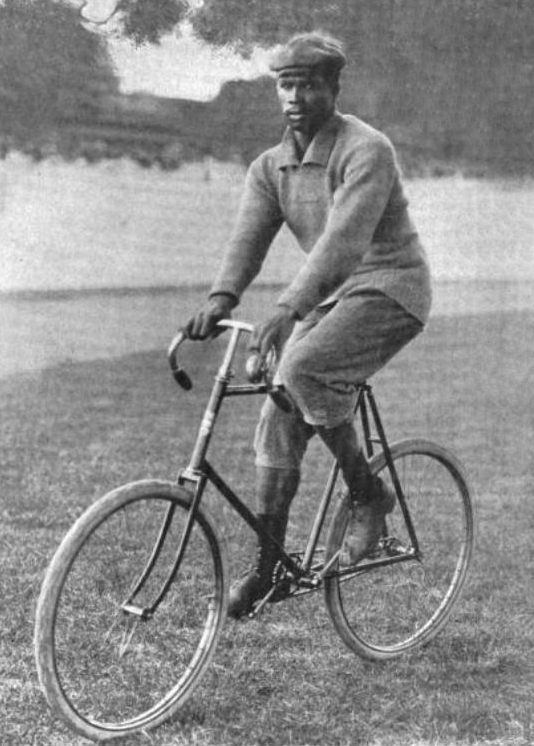

Frank Craig, The Sphere, 26 June 1901. No known copyright holder.

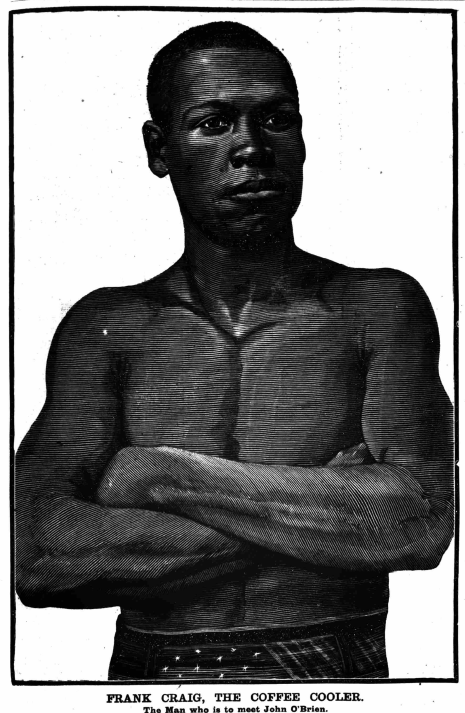

Frank Craig, before his fight with John O'Brien. Mirror of Life, 22 September 1894. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

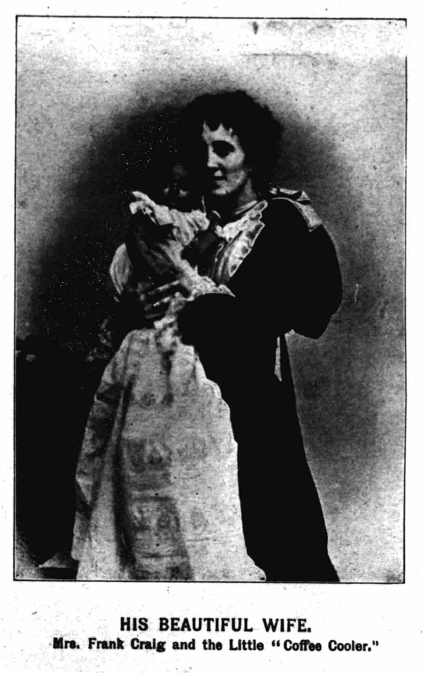

Louisa Shannon Craig and an infant Frank Jr, Mirror of Life, 2 June 1897. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

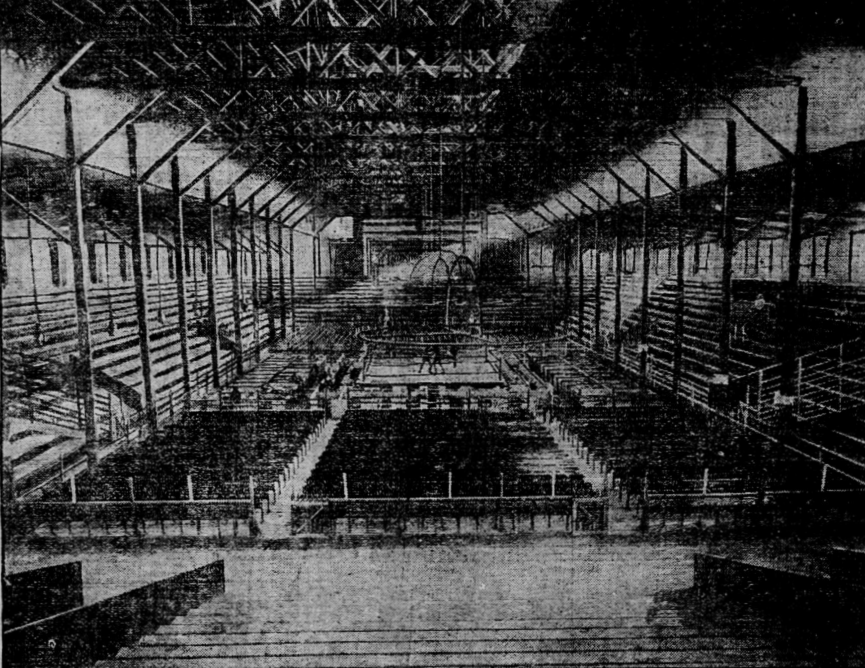

Coney Island Athletic Club boxing ring, 1899. Saint Paul Globe, 16 April 1899. Image courtesy of Library of Congress. Public domain.