All the World’s on Wheels

Jamie Barras

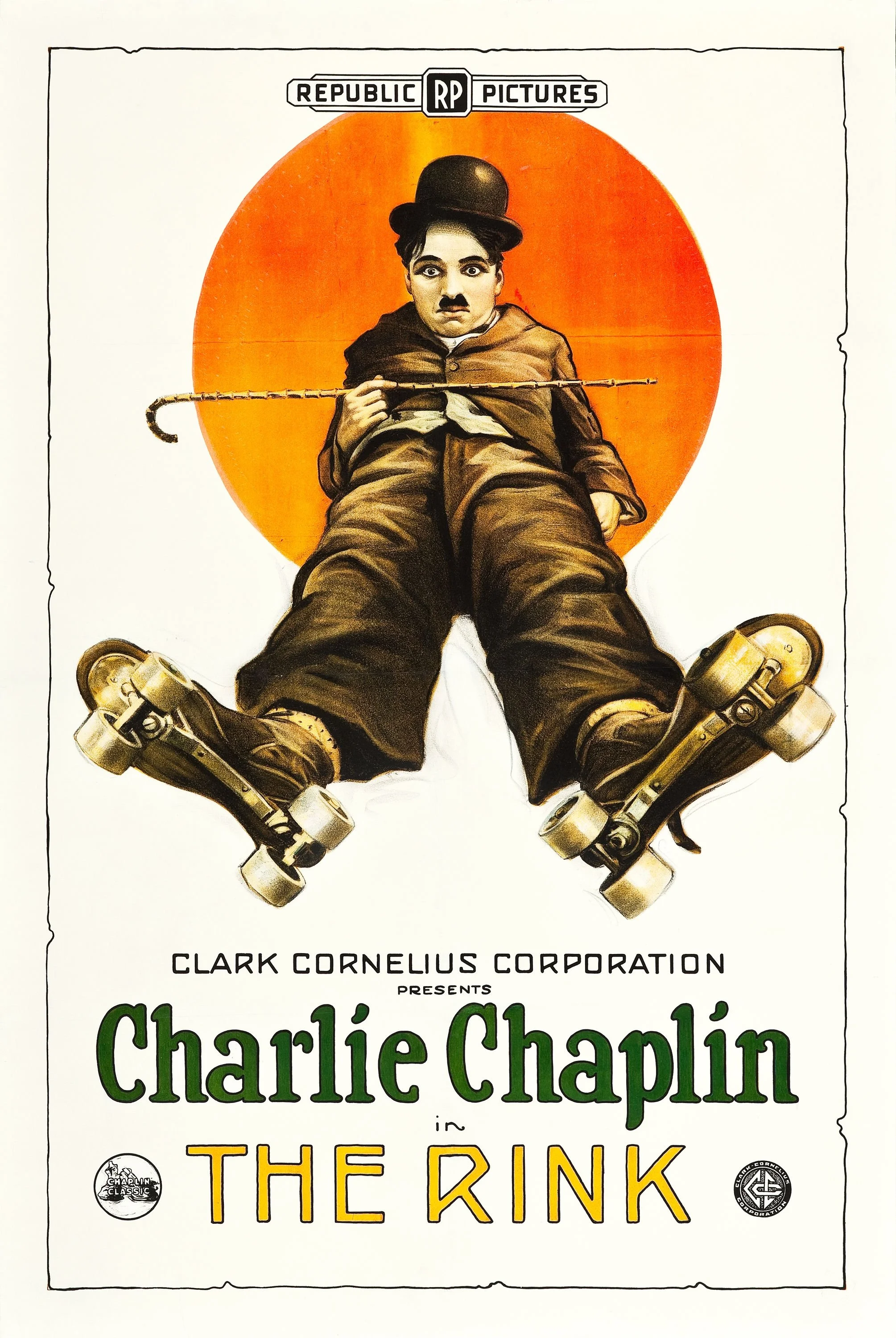

CHARLIE CHAPLIN IN “THE RINK”. This inimitable comedian, who is so much the rage, eclipses himself in his latest portrayal. “The Rink” is a two reel subject bristling with real humour, the incidents throughout being of a nature to compel incessant laughter. His gyrations on skates are a revelation, for while infusing plenty of fun into his representation, he performs marvellous feats that show him as perfect on skates as he is ridiculous in his ordinary walk.[1]

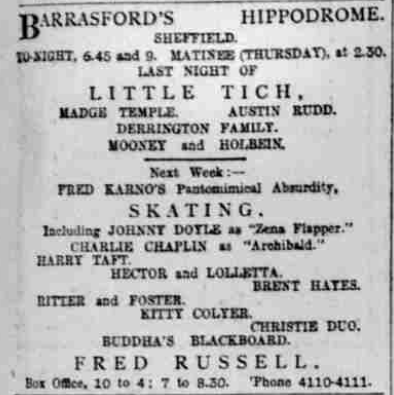

Any English reviewer writing in 1917 that Charlie Chaplin’s roller skating skills were a ‘revelation’ was displaying a remarkably short memory. Just seven years earlier, Chaplin had toured the halls in a rolling skating sketch while performing with Fred Karno’s Comedians; Chaplin had even been a member of the troupe’s ‘roller hockey’ team, playing the then-popular five-a-side sport in exhibition matches against local opposition to help drum up business.[2]

To be fair, by 1917, there was a war on, so people had other things on their minds; and the roller skating craze, which was at its peak in 1910 when Fred Karno satirised it on stage, had long since waned. Still, at its peak, it was a rare example of a pastime enjoyed equally by men and women, rich and poor, and one that spawned its own competitive scene that embraced both individual competition and team sports, again, for both men and women. Its stars earned a fortune by the standards of the day, and while not as famous as Chaplin would become—no one was as famous as Chaplin would become—were feted on four continents: the kings and queens of the roller rink.

RINKING. RINKING. All the World’s On Wheels. WEDNESDAY AGAIN—3 to 6 and 7 to 10. Get in practice and keep them running for soon there shall be Room, Time, Skates, and Prices to suit all.[3]

The history of ‘rinking’, as the pastime came to be called, is intimately wrapped up with the history of the technology that spawned it.[4] Although shoes with wheels are of 18th century origin, it was not until 1863 that Massachusetts-born James L. Plimpton patented the design for what is now known as the ‘quad skate’, the first practical roller skate, which is to say, one that allowed the wearer to control their direction of travel merely by leaning one way or another. Following the monopolist model of capitalism that America had made its own, Plimpton set about marketing roller skating as a fashionable pastime for the social elite, controlling access to the sport through his ownership of the patent and control of the organisation he set up to popularise it, the Roller Skating Association. It was only on the expiration of that 1863 patent 20 years later that roller skating experienced its Big Bang moment, with canny manufacturers and entrepreneurs joining hands to open large roller skating rinks in America’s major population centres based around a model of renting, not selling, skates to customers, something that brought the pastime within the financial reach of the general population. Rinking’s first US boom was on.

One thing to understand about rinking in this period was that it was seen as primarily a winter pastime: in Britain, most rinks closed their doors over the spring and the summer. So one attraction of rinking as a pastime was that the exertion warmed you up. At the same time, to a large degree, the main attraction was similar to that of dancing: it was exhilarating, could be fast-paced, and allowed social interaction with the opposite sex in a societally acceptable form. The appeal of rinking over dancing was that there was no right or wrong way to do it, provided you stayed on your feet. So, rinks developed a looser, more relaxed atmosphere than ballrooms and palais de danse.

Added to this, from a commercial standpoint, skating offered opportunities for competitive events of all kinds. As might be imagined, the crossover with sports developed for ice skating was almost one-to-one: as we will see, alongside ‘fancy’ (i.e., figure) skating, events like speed skating, endurance skating, and team-based sports developed, with the stars of one form of competition often also being the stars of other forms.[5]

Allie is a splendid specimen of the athletic American and in the course of his twenty-eight years has crowded more adventure into his life than half-a-dozen globe-trotters twice his age. He started life as a runner in his native country, and from that to expert cycling was an easy stage.[6]

A key feature of the competitive aspect of roller skating was the rise of the professional roller skater. At a time when most people’s level of physical fitness was determined by their job, in America, professional sportsmen and sportswomen emerged who followed a strict training regimen that was often created for them by another innovation of the period, the professional trainer. To the disgust of the gentlemen amateurs who had previously dominated sports, amateurs whose fitness was only of a general kind were no match for professionals who trained their bodies (and minds) to excel in the sports in which they competed. The physical, aerobic, and technical demands of roller skating gave ample scope for professional athletes to develop a competitive edge, making skating an attractive prospect.[7]

This was also when the idea of world records and world championships began to grip the public imagination—far in advance of the establishment of, on the one hand, universally recognized ways of recording and adjudicating record attempts, and, on the other, bodies that could organise international championships. A world record was a world record if someone said it was, and the same was true of world championships. In such circumstances, it was nothing for a professional athlete to boast of holding multiple world records and being the world champion in many events.[8] This was as true in rinking as in other pursuits.

This situation was also a recipe for competing claims. However, as a happy byproduct, bringing rival ‘champions’ together to race each other sold more tickets. To take just one example relevant to us here: In December 1909, the American speed skater Rodney Peters and his manager arrived in England and issued a challenge to ‘all the alleged champions now appearing before the public’. According to a letter that Peters’ manager sent to the Sporting Life, Peters was the current world champion at one mile, having also won the event the previous year. This would have come as news to the National Skating Association (NSA) of Great Britain, which had staged its first world championship at one mile a few months earlier, but never mind: the matter could simply be settled by staging a second NSA championship with Peters as a competitor. The latter event was held two months after Peters arrived in England, and Peters won; the circle was squared.[9]

The first US roller skating boom lasted until around 1900, when the pastime experienced a sudden and dramatic decline in popularity, which at the time was attributed to a management being, on the one hand, too slow to address the problem of female customers experiencing unwanted physical contact with men who deliberately crashed into them, and, on the other, wont to resort to cheap tricks to try to regain the customers lost to this ‘hoodlum’ behaviour. However, by the time interest had waned in the US, the pastime had taken off in Europe, where fresh innovations, chief among them dancing on roller skates, would eventually lead to a second boom in the US in the Edwardian era.[10]

It was only during this second US boom that the pastime also really took off in Britain. To understand why it took so long, we need to look at what happened in its early years.

THIS (THURSDAY) EVENING, THE 21st INSTANT AT EIGHT O'CLOCK, MR. CHARLES MOORE, The Unrivalled American Skater, WILL GIVE AN EXHIBITION ON PLIMPTON’S PATENT SKATES.[11]

Plimpton arguably achieved success earlier in England than in America, as he launched his patent roller skates in the middle of the American Civil War. However, this was following his favoured business model: promoting roller skating as a pastime for the social elite. Where Britain departed from America was in that in 1875, in Britain, a company called Spiller began manufacturing roller skates and renting them to the general public at commercial rinks in defiance of the Plimpton patent. This led to a brief boom in rink building, much as the lapsing of the Plimpton patent would in America eight years later. However, the Plimpton patent was still active in 1875. Plimpton filed a series of lawsuits against the Spiller Skates Company and any rink that rented out Spiller Skates. These lawsuits played out across the next two years, culminating in a final victory for Plimpton in 1877 and the shuttering of the businesses of the losing parties. This did such a thorough job of killing the craze for roller skating in Britain as a commercial concern that it could not even be revived when the original Plimpton patent lapsed in 1883 and America saw its first big boom.[12]

This is not to say, of course, that roller skating vanished from England following Plimpton’s court victory; the last two decades of the Nineteenth Century were the first golden age of British speed roller skating, several of whose star athletes we will encounter later. However, my focus here is on roller skating as both sport and popular pastime, and it was not until the Edwardian era, and the second US boom, that the bitter memory of the Plimpton suits and the financial ruin they had wrought had faded enough for commercial interests to make a second attempt to revive the pastime in England.[13]

Landing in Liverpool two years ago, with nothing of worldly wealth outside of the clothes he wore, a few more in a suitcase, an empty pocketbook, and a small physique filled with Kansas grit, one Topeka young man set out to make his mark in the world. Today, he is worth easily $200,000.[14]

The key figure in the Edwardian revival of the roller skating craze in Britain—for good or ill—was huckster Chester Parks Crawford (1870–1954), the self-styled ‘skating king of Europe’. Crawford, who hailed from Topeka, Kansas, had failed repeatedly in the family business of managing theatres before he found modest success running roller skating rinks. It was while operating a rink in Brighton Beach, Long Island, that he met Samuel Winslow of the Samuel Winslow Skate Manufacturing Company of Worcester, Mass. Winslow was convinced that the boom in roller skating rinks that America was experiencing could be spread to Britain, and offered to make Crawford the exclusive European agent for his skates if Crawford could demonstrate that he could make a go of running a rink in England. Crawford caught the next boat.[15]

Crwaford opened his first American-style rink—furnished with Winslow skates—in Liverpool in November 1907. It was an immediate success. In April of the following year, Crawford and Winslow joined with a Liverpool-based investor, Frederick Arthur Wilkins, to form the ‘American Roller Rink Company’. Under Crawford’s management, and with Winslow as a sleeping (if not secret) partner, the American Roller Rink Company acted as a sort of shell company, with each new rink project involving the creation of a new operating company with Crawford and Wilkins as the sole directors and largest shareholders, but all the investment coming from local interests. This approach was designed to afford maximum benefit to Crawford, Winslow, and Wilkins while leaving local investors holding the bag if the project was a failure. To add to the complexity of the web that the partners were weaving, Crawford owned the rights to a floor polishing machine that the operating companies were contractually obliged to use with a financial return for Crawford; they were also contractually obliged to use only Winslow skates, with a financial return for both Winslow and Crawford, as Crawford retained his role as the sole European agent for the Samuel Winslow Skate Manufacturing Company.[16]

In short, the American Roller Rink Company was, depending on your point of view, either a fine example of Yankee capitalism or a racket. By early 1910, the three partners, via their network of companies, operated 24 rinks in England and a further 8 in continental Europe, and were opening new rinks at a rate of one a month. So synonymous with the craze was the company brand that rivals began calling their own premises ‘American roller rinks’—Crawford having neglected to trademark the company name.[17]

The Olympia rink, which was opened last night, is without doubt the largest ever constructed. It is the fourteenth rink opened by Mr. Crawford in Great Britain in 13 months. A stock of 5000 pairs of bail-bearing skates is ready, and there will be three sessions daily for the next three months, at the hours of 10.30 to 12.30, 2 to 5, and 7.50 to 11.[18]

In December 1908, the American Roller Rink Company opened its largest rink to date. Conceived in association with impresario Charles B. Cochran’s annual ‘Mammoth Fun City’ winter fair at Olympia in West London, the rink, alongside its regular daily skating sessions, staged special events appropriate to the season, like masked and fancy dress balls and Christmas pantomimes, all on roller skates. This partnership with Cochran, arguably Britain’s greatest showman of the time, and his Fun City, which attracted millions of visitors to Olympia annually, placed rinking at the heart of mass-amusement culture. The multiple sessions, spread throughout the day and late into the evening, marked it as being for people of all ages and walks of life.[19]

To accompany the opening, Crawford announced a plan to stage ‘an international skating race’ at the end of the season. This plan would evolve over the next month into a world championship involving nine regional heats—to be run exclusively at American Roller Rink Company rinks, naturally—followed by a final at Olympia with £400 in prize money to be won (around £60,000 in modern terms), including £150 for the winner, well in excess of the annual earning of the ordinary working man or woman.[20]

It was at this point that the National Skating Association (NSA) felt the need to step in. The NSA had been established in Cambridge in 1879 to govern both ice and roller skating in Britain, with its most prominent role being the organising of the annual outdoor ‘fen skating’ races in East Anglia. (Fen skating, of ancient origin, became a competitive, amateur sport in the 1880s; it continues to this day.)[21] On hearing that Crawford planned to stage a roller skating championship, the NSA felt compelled to write to the press and point out that it had been holding its own roller skating championship annually since 1893, a purely amateur affair, and any skater taking part in Crawford’s [rival] event was risking losing their amateur status. A compromise was rapidly struck, and it was announced that Crawford’s event would be brought under the control of the NSA as the world professional roller skating championship at one mile, to be staged at Olympia. (The implication is that, in return, Crawford would underwrite the costs of the NSA’s amateur championship, but this is not certain.)[22]

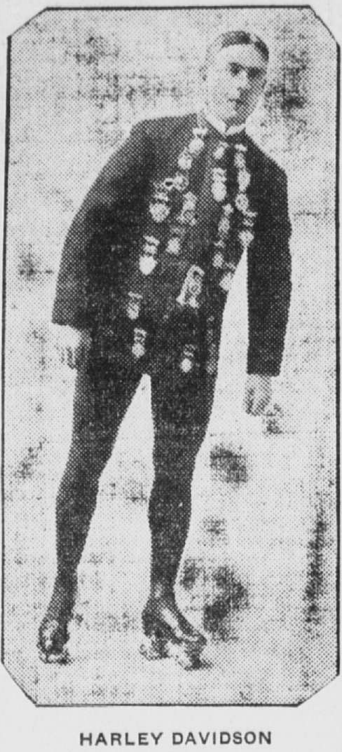

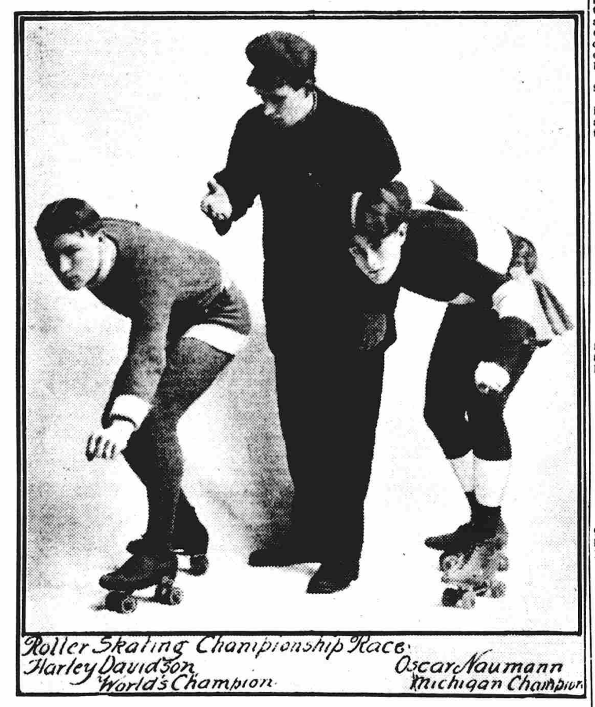

Key to the success of this professional championship would be its ability to attract international competitors, which, in practice, meant the best of the American professional skaters. It was something of a coup, then, when it was announced that the line-up would include roller skating phenoms Harley Davidson and Allie Moore.

Forty-three riders are entered for the short motor-cycle handicap, and among the machines in that event are several Indians, which, by the way, will have a powerful opponent, also from the U.S.A., in the two-cylinder Harley-Davidson, made by the famous roller-skate speed-man of that name, who thrilled Britishers at Olympia during the rinking boom of a few years ago.[23]

In actuality, Harley Payton Davidson (1873–1946) had nothing to do with the Harley-Davidson motorcycle company—the hyphen in the company name was for its two founders, William S. Harley and Arthur Davidson—although this would not prevent him from claiming otherwise in later years. Harley Davidson, the roller skater, was born in 1873 in St Paul, Minnesota, the son of a newspaperman. Davidson was the epitome of the American professional athlete of the period, excelling at ice skating, roller skating, cycling, baseball, and other sports. In common with many professional roller skaters, he also managed roller rinks. By the time of his arrival in England in early 1909, he was the holder (by his own account) of 179 winners’ medals. He was also the first winner of the Harmon Cup—the ‘world championship at one mile’ that Rodney Peters would win in subsequent years.[24]

Described as ‘shortset, agile, and full of life’, and having a figure that was the ‘athletic ideal’, Davidson was a walking, talking advert for roller skating as physical exercise. ‘Roller skating,’ he told reporters, ‘is one of the finest forms of exercise anyone could take up. I do not know of anything else in the line of amusement that is so beneficial in so many different ways. It develops a finer and more supple muscle than any other exercise.’[25]

In common with many professional athletes in this period, Davidson had several equally athletic siblings, including fellow professional roller skaters, John and Fanny Davidson (as we will see, John Davidson was to become another of the entrants for the professional championship). Meanwhile, Mabel Davidson, Harley’s older sister, was known primarily as an ice skater, dubbed ‘Mab, queen of the ice’. She toured France and England to great success in 1896 and 1897, but then tragedy struck: she contracted tuberculosis on the trip and died on her return home at the very young age of 24.[26]

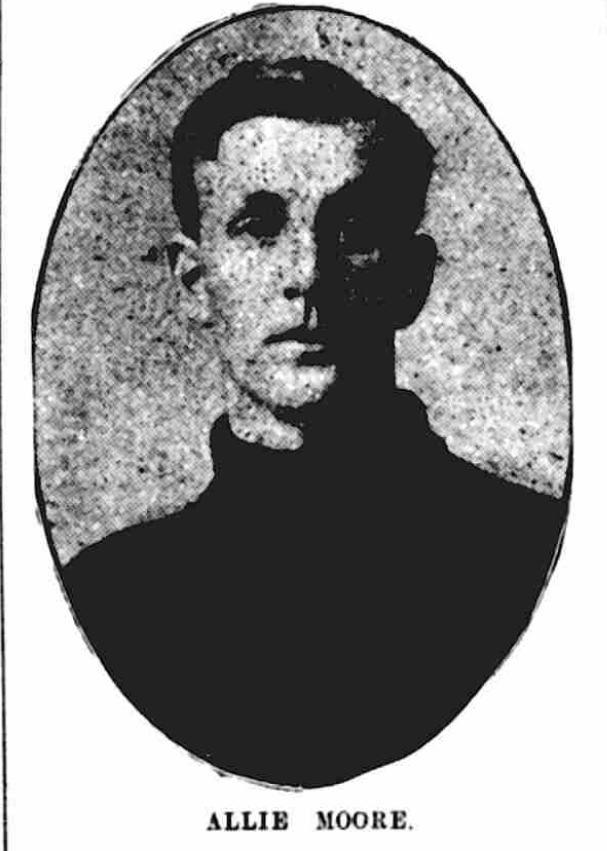

Allie Moore was born at Charlevoix, Mich. Until three years or so ago, he was a sailor, and in addition to his records made on rollers, is a clever athlete and boxer. He is built on powerful lines and skates from the hips.[27]

Allie Moore (1883-1955) was another all-around athlete. However, whether he had any genuine claim to the world roller skating titles he professed to hold was contested, not least by Rodney Peters. Born in Charlevoix, Michigan, in 1883, Moore’s first, and arguably only true, love was sailing. At the same time, he applied his natural athleticism to a number of sports, including running and cycling. Whereas Davidson was primarily a competitive skater and rink manager, Moore developed a career in ‘fancy’ (figure) and trick skating, skating down narrow beams, jumping over chairs, etc., to complement his racing.[28]

ROLLER SKATING RACES A larger crowd than ever assembled at the Sheffield Artillery Drill Hall Rink last evening to see Harley Davidson skate his heat. There were five starters: Davidson, Swift, Jacques, Harpham, and Green. Straight from the pistol, Davidson took the lead, and rapidly gaining, soon lapped his opponents. Davidson, going finely, lapped the others, with the exception of Jacques (twice) altogether three times, coming in an easy winner in 3 mins. 45 secs.[29]

Although they liked to present themselves in the press as rivals, in fact, Harley Davidson and Allie Moore were friends, and Moore had travelled to England in the company of Harley’s younger brother, John F. Davidson, who was Moore’s coach as well as a racer himself. Moore was taking part in the championship races at the personal invitation and under the management of Chester Crawford, the event organiser, who billed Moore as ‘the world champion’ (at what was never said). So, although Moore and John F. Davidson did not even set off from America until after the preliminary heats had concluded, they were allowed to move straight to the London regional heats, a decision that was not without controversy.[30]

Moore and the two Davidson brothers, almost certainly by Crawford’s design, raced in separate preliminary heats in the London regional final, which was held at Earl’s Court in London on the 23rd and 24th of February 1909. Two of the other preliminary heats featured Bill Curtis and A. Terry, two veteran former British amateur champions. Curtis had been one of the best speed roller skaters in the world back in the 1880s; however, he, like Terry, was now well past his prime. All five of these skaters made it into the semi-finals, alongside a fourth American skater, D.D. Bennett. Again, almost certainly by design, Allie Moore and Harley Davidson raced in separate semi-finals. Moore and John F. Davidson came in first and second in their semi-final, leaving the nearly 50-year-old Curtis a long way behind, while Harley Davidson and the other American, Bennett, finished ahead of Terry in their race. The four Americans, therefore, advanced to the final of the London regional event, where Allie Moore and Harley Davidson would finally race against each other.[31]

As only the winner and runner-up of this regional final were guaranteed to go through to the championship races, there was, in theory, a chance that one of the championship’s two biggest draws could be eliminated before contesting the championship. However, in the event, a) Allie Moore won the final preliminary race and Harley Davidson was the runner-up, and b) all four racers went forward to the championship races. Although the press did not comment on the latter, at first glance, strange result, it implies that there was a provision in the rules for the two fastest losers of the regionals to also go forward. Results printed in the newspapers show that this final London race was the fastest of all the regional heats by quite some margin. Thus, in practice, there seems to have been little risk of either Allie Moore or Harley Davidson being eliminated. Regardless of the circumstances, all four American racers were now through and would compete against the fifteen winners and runners-up of the other regional heats.[32]

The finals of the 1909 NSA Professional World Championship at One Mile took place at Olympia on the evening of Friday, 26 February. There were four preliminary heats. Allie Moore and Harley Davidson were again kept apart. Harley Davidson skated in the same heat as his brother and the pair openly acted as pacemakers for each other to ensure not only that they finished well ahead of the other competitors but also that John F. Davidson advanced to the final as the fastest loser (Harley, of course, won the heat). The three other heats were won by Moore and two Britons: the current NSA amateur champion, Charlie Wilson, who had turned professional to compete in this event, and P.F. Powell.[33]

In the Final, Harley Davidson, going wide, caught Allie Moore napping after the fifth lap, and the last-named could not get through until Davidson had gained a lead of fifteen yards. When Moore got going again he had no chance of catching the leader, and Davidson won by 10 yards.[34]

In what was considered an upset, Harley Davidson won the final race, crossing the line in a time of 2 minutes and 51 and 3/5s seconds (making for an average speed of just over 20 miles per hour), ten yards in front of Allie Moore. Charlie Wilson came in third, and John F. Davidson fourth, Powell coming up the rear. Of course, this was only judged an upset because Moore had won the London regional final and Crawford had promoted him as ‘the world champion’. However, as we have discussed, the result of the London regional final was irrelevant to progression to the championship races, and there was no such thing as the world champion in any event in roller skating. Moore was arguably not even a world champion at one mile, as, unlike Harley Davidson, he had never won the Harmon Cup, the American event that called itself the world championship at that distance—something that Rodney Peters and his manager would be keen to point out when they arrived in England later in the year.[35]

Added to the above, Harley Davidson was far and away the more experienced skater—Moore, athletic and gifted as he was, had only been skating professionally for a few years; Davidson for nearly 20 years. The final factor to consider was John F. Davidson. The Davidson brothers had helped each other into the final by pacing each other in their semi-final. Although the newspaper account of the final—presented above—appears to be missing a key sentence, it is clear from the language used (Davidson going wide, Moore unable to get through) that someone blocked Moore. This was almost certainly John F. Davidson executing a pre-planned move on behalf of his brother (this despite the younger Davidson also being Moore’s trainer—all’s fair in roller skating). In short, the result was almost a foregone conclusion, not an upset.

At first glance, this would seem not to be the result Crawford was hoping for, as his man was defeated. However, on closer examination, it was a gift to Crawford, as it paved the way for a rematch—Moore, the defeated ‘champion’, out to ‘restore his honour’. The way that this was presented to the public was that Allie Moore, dissatisfied with his performance on the day of the final, issued a challenge to Harley Davidson via the column of the Sportsman newspaper for a rematch for a prize, provided by Moore, of £25. Davidson, in response, accepted the challenge on the condition that it be for £50, winner-take-all.[36]

It will be remembered that Moore and the Davidson brothers were friends and some-time travelling companions; they did not need to converse via a newspaper. Not only this, but one week before this exchange, John F. Davidson had created the ‘International Professional Skaters’ Association’ to represent and promote American professional skaters in Britain, and Allie Moore and Harley Davidson were founder members. The exchange via the Sportsman was just a clever bit of self-promotion.[37]

Allie Moore and Harley Davidson raced each other at Earls Court over one mile on 30 March 1909 and over two miles on 3 April 1909; Davidson won both races. However, this was just the beginning; there were further races at one and two miles in Manchester in May, this time, in best-of-three contests. Davidson was usually the victor, but Moore won just often enough to keep things interesting. The two also faced off against each other in special events staged alongside championship races involving other skaters, such as at the English championship heats at Norwich, also in May.[38]

However, there were only so many times they could draw from that same well, and by June, as the competitive season ended, Harley Davidson had found a new outlet for his talents: a ‘trick, fancy, and acrobatic skating’ act with a female partner.

We are informed by Mr. Harley Davidson that his protégé and pupil, Dolly Mitchell, a charming young lady of sixteen summers, has made such remarkable progress that he will, in future, include her in his own act. Mr. Davidson adds, “In all my career, I have never seen anybody equal her. She has had but six months' tuition, and during that time has won every lady's skating competition entered by her in Scotland.[39]

Public opinion about women athletes in the early modern era tended to vary in direct proportion to the extent that women athletes were seen to depart from the ‘feminine ideal’, which is to say, the more strenuous the sport and ‘masculine’ or revealing the attire, the less that public opinion liked it. It is for this reason that women’s football remained an anathema until, arguably, the dawn of the Twenty-First Century. As J.A. Kennard writes in regard to women’s sport in the Victorian era, ‘Women's sport was conditioned by the powerful bias of the feminine ideal in relation to techniques, equipment, clothing and playing facilities. The more attention the sportswoman paid to these requisites, the more favorable was public opinion. Even the most ardent protagonists of women's sport held some reservations in connection with strenuousness, roughness and endurance, particularly with reference to team sports.’[40]

It is interesting in this context to note the extent to which the press surrounding roller skating was keen to emphasise how ‘charming’ (for which, read ‘feminine’) women looked when roller skating.

The rinking girl is an apotheosis of her dancing sister. When a lovely woman is mounted on rollers, she is perfectly irresistible. Her natural grace is magnified a hundredfold, and to look at her is to admire.[41]

It is quite certain that a woman never looks better than when she is skating, if she can skate; it is almost as little open to doubt that a pretty girl who can skate is never more appealing than when she is trying to learn. If she can fall gracefully, she is, in these circumstances, perfectly irresistible.[42]

This bias, when it came to women and sport, was no more apparent than in public reactions to the emergence of women’s cycle racing in the last decade of the Nineteenth Century, with one cycling-focused magazine describing the entirely practical and fit-for-purpose outfit worn by one young female racer as ‘…of a most unnecessary masculine nature and scantiness’.[43] Cycling is of interest to us here because, as we have already observed, many of the male professional roller skaters were also stars of the cycling world. The same was true of the female professional roller skaters who appeared on the rinking scene during its Edwardian boom. Promoters of roller skating also made much of the perceived connections between the two sports in terms of health benefits and the crossover in required skills: ‘Skating is akin to cycling, in that it is a pastime in which balance is the first essential to skill’.[44]

The most remarkable of the women professional skaters to rise to prominence in this era was a cyclist. Her name was Nellie Donegan, and her career was remarkable, not least in the way in which she represented the change in presentation of women in sport from the late Victorian to the Edwardian eras.[45]

[Nellie] Donegan has been termed the “Genée on wheels.” She is an Australian by birth and is the only lady in the world who has run 100 yards under eleven seconds. She has been described as the best all-round athlete under the British flag, engaging in fast cycling, running, shooting, hurdle jumping, and now roller-skating.[46]

Ellen ‘Nellie’ Donegan (1878–1945) had been roller skating professionally for at least 16 years by the time the above article was written (July 1909). She was primarily a music hall artist and circus performer, rather than a sportswoman, despite her publicity matter; however, she is of interest to us here as an athlete who moved easily between the worlds of cycling and roller skating. She was born in Australia, the daughter of Irishman James E. Donegan and Australian Hester Donegan, née Hickson, and got her start on the stage in the act that her father created, the Dunedin troupe of trick cyclists. The troupe also included her sister, who performed under the stage name Maudie Dunedin (1886–1937), and brother Jimmie Donegan. The two Donegan sisters also appeared together in acts spun out of the Dunedin troupe (e.g., the Donegan Sisters, Dunedin Lady Trick Cyclists, etc.).[47]

By 1893, alongside the family cycling act, Nellie had developed a solo act as a ‘skate dancer’, performing in roller skates on a raised podium on the music hall stage (as an aside, on at least one occasion, the Dunedins and Nellie Donegan shared the bill with Charles Chaplin Sr—father of Charlie Chaplin).[48] Nellie continued performing with her family and as a solo act until 1900, when she married fellow music hall artist, American-born William Andree, and retired from the stage. A year later, she gave birth to twin daughters in London, named Maudie and Ellen in honour of their aunt and mother. The new family moved to the US and settled in Andree’s hometown of Chicago. Alas, their happiness was to be short-lived, as, in 1907, tragedy struck when William Andree died aged just 36.[49]

Faced with having to raise two little girls on her own, Nellie went back on the stage. It was while appearing in the ‘Roller Skater Ballet’ sequence in the 1908 revival of the Florenz Ziegfeld show ‘A Parisian Model’ that she met Indiana-born professional skater, [Adams] Earle Reynolds (1868–1954). Reynolds was a journalist and a jockey as well as a skater, and, in 1897, had designed a pair of ‘bicycle skates’ that he wore in a race against champion cyclist Charles J. Fox (Reynolds won). Reynolds had taught Broadway star Anna Held to roller skate for the original run of ‘A Parisian Model’ in 1906 and was the choreographer and coach for the roller skating sequence in the 1908 revival. Donegan and Reynolds became a couple not long after meeting. In one version of events, they married not long after, and boxer Gentleman Jim Corbett was their best man, but this may have been a showbiz yarn, as there is evidence they did not finally marry until 1913. Regardless, shortly after becoming a couple and following a brief period teaching ice skating in New York, they formed a roller-skating double act that they toured around the US and Canada. Then, they set sail for England, opening as ‘Reynolds and Donegan’ at the Palace Theatre in London in April 1909, under the auspices of John F Davidson’s International Professional Skaters’ Association.[50]

My wife excels in everything she attempts, and is accounted the greatest all-round athlete that America has ever seen. As a sprinter, she won all the ladies’ short and long distance events in Australia, and last season in Chicago, she ran 100 yards in 10 4/5s with hardly any training. She was world-famed as the most wonderful woman cyclist when with the Dunedins, and is a splendid trick rider. At the time, she won every ladies’ speed event at the Association athletic games four years in succession, and has taken dozens of prizes at shooting, hurdling, jumping, lacrosse, and hockey.[51]

What is remarkable about what Earle Reynolds had to say about Nellie Donegan’s athletic achievements on their arrival in London was not how impressive they were, as they were also certainly made up, but that Reynolds saw the value in promoting his wife as an athlete rather than a performer.[52] This aligns with how Reynolds, like Harley Davidson, Allie Moore, and others, presented himself and his wife as roller skaters: as professional athletes. It also spoke to how Reynolds and others presented the benefits of skating as a pastime for both men and women. We have already seen how Harley Davidson extolled the virtues of roller skating as a form of exercise. In that same interview, he said, ‘A mild exercise, developing a long, soft ‘muscle’ is what is called for nowadays, and that is why roller skating is such a great thing, particularly for ladies. It is so mild that they do not notice the exercising.’[53]

After a long engagement at the Palace Theatre in 1909, Nellie Donegan and Earle Reynolds returned to the United States. However, they were back the following year for a further long engagement. This set the pattern for the next three decades, interrupted only by the First World War. First as a duo and later as a family act with Nellie’s daughters from her first marriage, Maudie and Ellen, they performed their roller skating act across four continents. In later years, they toured the US with the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus with an act they called the ‘Reynolds and Donegan Skating Girls’. It was while performing with Ringling Brothers that they became caught up in one of the worst tragedies to ever strike the world of American entertainment, the Hartford Circus Fire, which claimed the lives of 167 people and injured 700 others on 6 July 1944. Nellie was said to have never recovered from the trauma of what she experienced that day. She died just one year later, aged 67.[54]

Although remarkable for its longevity, Nellie Donegan’s career shared many elements with those of other women roller skaters who made a name for themselves during the craze’s Edwardian heyday, including coming from a family with a history of athletic pursuits. As we have already discussed, Harley and John Davidson’s sisters, Fanny and the tragic Mabel, were also professional skaters. Harley Davidson’s experience of training alongside his sisters almost certainly contributed to him taking on a female partner of his own. Her name was Dolly Mitchell, and although we know much less about her than we do Nellie Donegan, what we do know offers an interesting comparison and contrast to the life and career of the latter.

Two years ago, Miss Mitchell left school and learned to rink. Later, she became a professional when Councillor Bostock gave her her first engagement at the Zoo, Glasgow, rink. There she became an instructress, and when on one of his visits to the Zoo, Harley Davidson saw the young lady, he was greatly struck by her easy carriage on the floor and the many daring “flights” she essayed from time to time. It so happened that Miss Mitchell's two brothers and mother are good skaters and were present when Mr. Davidson made the proposition of a business partnership being formed. They liked the suggestion, […] Miss Mitchell liked it too.[55]

Elizabeth “Dolly” Mitchell (1893–?) was the great-granddaughter of Aberdeen whisky distiller John Begg. According to Harley Davidson, Dolly had been an invalid as a child, suffering from ‘hip-joint’ disease, but her doctor father (John Begg Mitchell) had ‘cured’ her. The timing of the Davidson–Mitchell partnership is interesting in that it began sometime in June 1909, with their first professional engagement in July. It will be remembered that Nellie Donegan and Earle Reynolds arrived in Britain in April 1909 and were signed to the International Professional Skaters’ Association, the organisation founded by John F. Davidson, of which Harley Davidson was also a member. Although it cannot be said with certainty that Harley Davidson was inspired to seek out a female partner after the success of Reynolds and Donegan at the Palace Theatre in London, it is interesting to note that their publicity used the same language as that of Donegan and Reynolds: ‘Everyone who has seen Genée and Vincenti execute a duet dance knows what intricate and difficult movements these great artists employ. What, then, will be said of two other artists who duplicate the most involved steps of Genée and Vincenti—on roller skates?’[56] Whatever the inspiration, it is clear that the two acts were quite similar, with the main difference being that Donegan and Reynolds performed their act on stage in London, while Davidson and Mitchell toured theirs around the province. It is also worth noting that both acts were promoted by John F. Davidson.[57]

Harley Davidson and Dolly Mitchell performed together across the second half of 1909, the partnership ending with Harley Davidson’s return to the US in early 1910. Dolly Mitchell continued to perform as a solo roller skating act, billed as ‘Dainty Dolly Mitchell’, ‘Britain’s Champion Lady Skater’ and the ‘Idol of the Skatorial World’, for at least the next two years, touring the UK chaperoned by her mother, Elizabeth Mitchell. She then disappeared from public view.[58]

It is worth noting here that, at 16, Dolly Mitchell was far from the youngest roller skating star of this period. Also signed to John F. Davidson’s Professional Skaters’ Association was ‘“Baby” Lillian Franks, age nine, the most wonderful child skater in the world.’ In fact, Lillian Elizabeth Franks (1896–1993) was closer to 13 when she toured the British roller rinks in 1909. She was the daughter of roller skating duo Charles Lincoln Franks of Pekin, Illinois, and Margaret Franks née O’Neil, and was born in her mother’s home province of Newfoundland in August 1896. The family left the US for Britain in January 1909, where Charles Franks found work as a rink manager, while his wife and child toured the UK. The family then travelled on to continental Europe, performing as far east as Russia, before returning to the US in 1913. Lillian went on to marry Charles Sarnelle/Sannela, a Brooklyn garage owner.[59]

To conclude this brief diversion into what might be termed roller skating ‘novelty acts’, inevitably, several animal acts also got involved in the craze. Chester Crawford debuted a roller skating elephant act at the American Roller Rink Company’s Hippodrome rink in Paris in March 1910. Mercifully, Crawford does not appear to have attempted to bring the act to England. There were, however, various roller skating chimpanzee acts at large in Britain in this period. Animal trainer Charles Judge debuted the first of his many acts featuring roller skating chimpanzees in 1909. Judge would still be touring chimpanzee acts around the halls into the 1930s. And then there was Consul. There were actually many performing chimpanzees of that name in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries—so many that the name was co-opted for a mechanical calculator toy (‘Consul, the Educated Monkey’). The Consul that appeared in Britain in 1910 was brought from America by Scots-born animal trainer and showman Frank Bostock.[60]

Let’s move on.

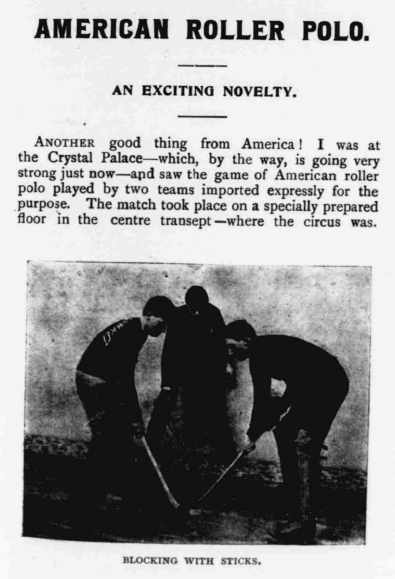

The game of roller polo, as played by two American teams at the Crystal Palace, is like nothing so much as hockey on the ice. Each team consists of five men. They use the ordinary hockey sticks, and have their legs padded—a very necessary precaution. The goalkeepers wear, in addition, a kind of bulletproof shield, indispensable, for the shots at goal are numerous and violent. The ball is about the size of a cricket ball, weighs about 150 oz, and is made of wool, yarn, and paper compressed by hydraulic power.[61]

Next to the speed skating races featuring individual stars like Harley Davidson and Allie Moore, the most important sport connected to the Edwardian rinking boom was unquestionably roller hockey. As we saw at the start of this article, the sport was so popular in 1910, Fred Karno used a roller hockey team to promote his roller skating music hall sketch, with Charlie Chaplin starring in both. The sport began life under the name ‘roller polo’ in the US in the dying days of the Plimpton patent, and was originally played by teams of seven players.[62]

Although there is some evidence that a version of the sport was played in Dublin as early as 1895, it did not come to public attention in England until two American teams arrived in 1900 to play a series of exhibition matches. However, these matches were played at Crystal Palace, which was primarily an amusement park, and, therefore, viewed principally as simply for entertainment (it didn’t help that the venue used was that usually used by visiting circuses). In addition, rinking was simply not popular enough, and rinks close enough geographically, for there to be any thought of any kind of competitive league being formed.[63]

By 1909, two years into the British roller skating boom, that situation had changed. Under its new name of ‘roller hockey’ (introduced in 1907), it found favour in Northern England and Central Scotland. By September of 1909, a men’s Northern Roller Hockey League had been formed in Lancashire, with teams from Wigan, Chester, Manchester, and Bolton. (Wigan would be where Charlie Chaplin would make his roller hockey debut in February 1910). By November, Wigan also had its own women’s roller hockey teams. Women’s teams also emerged in Northampton and London around the same time.[64]

November 1909 was also when roller hockey teams began to emerge in Lanarkshire, Scotland, centred on Glasgow, with the star team being that of the Glasgow Zoo rink (the rink, it will be remembered, where Dolly Mitchell was an instructress), but teams also in Paisley and Motherwell. There is some evidence that the game played in Lanarkshire involved teams of seven, not five, players, as in its early days in the US. There were also ‘inter-city’ matches between teams from Glasgow (Zoo rink) and Edinburgh (Olympia rink). Women’s teams would follow in 1910.[65]

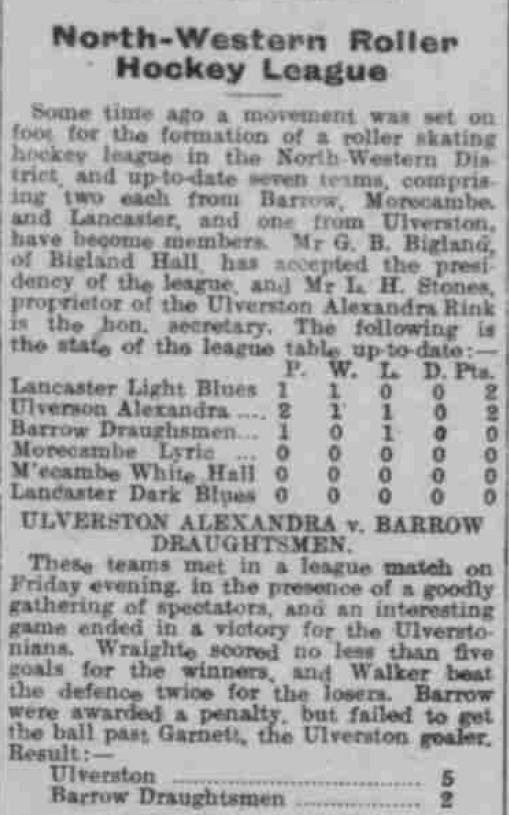

By the beginning of 1910, the sport had reached Wales. It had also spread across the whole of the Central Lowlands of Scotland, with strong representation in Falkirk, Edinburgh, and Glasgow. Similarly, from its central Lancashire base, the English game had spread north along the Lancashire coast to Morecambe, Lancaster, and Barrow, which became the basis of a North-Western Roller Hockey League. Match reports, results, and league tables were now being printed in the sports pages rather than the news pages of the local papers.[66] The first international was even played, with a team representing England (Southern Counties) taking on Ireland in Dublin in April 1910 (England won 7–2). By the end of 1910, there would be roller hockey leagues in both the north and south of Ireland.[67]

All that was missing at this early stage of the sport’s development was a national association, equivalent to the Football Association, to bring all these regional efforts together under a unified code of rules, along with a national open competition, equivalent to the FA Challenge Cup. Alas, the sport never had the chance to achieve these milestones. (It should be noted that, as early as 1896, there was a ‘Rink Hockey Association’ in London, operating out of Crystal Palace, and by the 1920s the ‘National Rink Hockey Association’ was the governing body for roller hockey—indeed, in 1930, it changed its name to the ‘National Roller Hockey Association’ to better reflect this—however, in its early life, the ‘Rink Hockey Association’ was the governing body for what we would call today ice hockey.[67i]) Even as roller hockey was expanding across the UK and Ireland in the winter and spring of 1910, the wheels were coming off the roller skating boom. And Crawford, Winslow, and Wilkins were at the heart of what had gone wrong.

RINK COLLAPSE AT BRADFORD. A CRAWFORD AND WILKINS RINK CLOSES DOWN AT SHORT NOTICE. The American Roller Skating Rink at Bradford has closed its doors. The Bradford American Roller Skating Rink Company, Limited, was formed in November, 1908, with a share capital of £9,000, half of which shares were allotted, credited as fully paid, to Mr. C. P. Crawford and Mr. Fred. A. Wilkins, the promoters, upon flotation. These gentlemen also received a joint salary of £8 per week, as managing directors, and other privileges.[68]

Ultimately, like most boom-to-bust phenomena, it was market oversaturation that killed the Edwardian-era roller skating craze. By the winter of 1909, there were 300 roller rinks in Britain.[69] So many rinks had been built across the spring and summer of 1909 in anticipation of a rush of customers in the 1909/1910 winter season that, as many customers as there were, there simply weren’t enough to go around. Added to this, the rush of customers had started to slow and would soon reverse with the rise of the Picture Palace; movie-going was beginning to replace roller skating as a popular night out. (As an aside: one of the pioneers of cinema building in London was the notorious Montagu Pyke, a huckster who ran his Amalgamated Cinematograph Theatres Ltd company on the same basis as Crawford, Winslow, and Wilkins ran the American Roller Rink Company: each cinema in the Cinematograph chain was its own limited company in which all the risk was carried by local investors and all the revenue went to Pyke.)[70]

This downturn in customers hit rinks that had higher-than-average costs particularly hard, as they could not compete by lowering prices. Chief among the latter were the American Roller Rink Company Ltd rinks. As discussed above, the business model that Crawford, Winslow, and Wilkins pursued diverted most of the revenue (not profit, revenue) into their pockets, funnelled out of the operating companies they set up to run their rinks in the form of salaries, dividends, and license fees payable to the three men. This left the businesses so cash-poor that the least drop-off in revenue rendered them nonviable. American Roller Rink Company rinks started to fail one after another in January 1910. The first to go was the Sheffield rink, but within a couple of weeks, the rink in Bradford had closed, and the rink in Aberdeen failed at around the same time.[71]

Of course, it wasn’t just American Roller Rink Company rinks that failed—the same week that an American Roller Rink Company rink failed in Bradford, an unrelated rink failed in Leeds—but the failure of the American Roller Rink Company rinks had the greatest impact, because this revealed the extent to which Crawford, Winslow, and Wilkins had stacked the deck in their favour, with Bradford- and Sheffield-based investors left wondering how businesses they knew to be pulling in hundreds of pounds every week could fail at a day’s notice. The final verdict on the failure of the Bradford rink was a telling one: ‘The failure of the company was attributable to mismanagement in consequence of the promoters having too many concerns to look after in England and the Continent’.[72]

By March of 1910, just two months after its first rink failure, it was all over for the American Roller Rink Company, a spectacularly rapid fall from grace. The company’s assets were sold to the International Rink Operating Company Ltd while its debts remained with the original company. This was not the end of the story, however, as the chief backer of the International Rink Operating Company was Samuel Winslow, the sleeping/secret partner in the American Roller Rink Company, and Crawford and Wilkins were two of the shareholders. As would be revealed later, this move was simply a scheme to leave behind any debts the former company might incur due to lawsuits filed by shareholders and creditors of its rink operating companies.[73]

However, this scheme resulted in a falling-out between the partners, with Wilkins taking the other two men to court, claiming that Winslow and Crawford had walked off with all the assets leaving him with all the debts (which, it has to be said, was rich, as Wilkins had entered into the scheme with the intention of leaving the satellite company shareholders and creditors with all the debts). The suit failed because Wilkins could not prove that Winslow was a partner in the American Roller Rink Company or that the International Rink Operating Company was anything other than an act of philanthropy by Winslow to aid two former business associates (i.e., licensees of his skates) whose company was facing a crisis from which it could not recover. It is worth noting that the case was covered in depth by the Financial News, a newspaper that had been warning since the summer of 1909 that the roller skating craze was a house of cards and the American Roller Rink Company was on the shakiest of foundations.[74]

In a sequel to this case, the creditors of one of the American Roller Rink Company’s other failed rinks, which had traded under the name the Aberdeen Skating Rink Company, took Crawford, Wilkins, and Winslow to court to recover the debt, naming them, again, as the three partners in the American Roller Rink Company and claiming that, as the parent company, this was responsible for the debts of the Aberdeen operating company. Winslow once again argued in court that there was nothing to connect him with the American Roller Rink Company; he simply supplied it with skates. Meanwhile, Crawford and Wilkins used the defence that they had built into their business model: the debts were not those of the American Roller Rink Company, but those of the operating company, which had been wound up back in February 1910. To the chagrin of the Financial News, which also covered this case in depth and clearly hoped for a judgment that would settle the matter of what exactly had gone on in the American Roller Rink Company, the case was settled out of court.[75]

Ultimately, it was Chester Crawford’s own lack of business acumen that brought him down. In an echo of his failure to trademark the American Roller Rink name, in January 1912, he took over the lease of a failed roller skating rink in Newcastle Upon Tyne with a view to turning it into a dance hall without first determining if a license could be had for such a use. It could not, and the business failed with debts of £2000, which wiped out the money he had received from Winslow at the transfer of the assets of the American Roller Rink Company to the International Rink Operating Company. There were further business failures in the next few years, including in theatrical ventures, a business that Crawford had already failed repeatedly in before he arrived in the UK. To the immense satisfaction of the Financial News, in April 1917, Chester Crawford was declared bankrupt with debts approaching £10,000, a small fortune at the time.[76]

Never one to let failure hold him back, Crawford returned to the United States and, within ten years of his UK bankruptcy, had opened the Rollerdrome in Culver City, California, at the time, the largest roller skating rink in America. The extent to which he was able to recover his fortunes so quickly due to the true nature of his financial arrangement with Samuel Winslow, undisclosed at the time of his bankruptcy, is unknown. He died in California in 1954.[77]

CHESTERFIELD ROLLER SKATER IN AMERICA To the Editor Sir, —I do not know whether you will remember me or not, but from 1909 to 1913 I played roller hockey for the Premier Rink on West Bars, Chesterfield, against some of the best teams in the Midlands, and in addition I hold the Webb Challenge Cup and won the Sheffield and District Championship and also the Northern Counties Championship. […]Since returning [to the US] after the Great War, when I served with the Royal Flying Corps, I have been successful in breaking the world’s one half mile roller skating record, world’s 9, 11, and 21 hours records […] I have also won with a partner five six-day races in New York and other cities.[78]

Of course, the end of the roller skating boom was not the end of roller skating in Britain; it was simply the end of it as a mass public entertainment. Speed skating races administered by the National Skating Association continued until the advent of the First World War, and then picked up again after the armistice. Roller hockey grew into a niche international sport (known as ‘rink hockey’ in the US[79]) that continues to this day. Roller skating as a ‘fad’ would also re-emerge every few decades, usually in association with innovations in presentation (roller discos, roller derbies) or technology (it is worth noting in this respect that inline skates, seen as a modern innovation, have actually been around since the earliest days of the pastime; it is just that they did not become a commercially viable product until modern times[80]).

Like all booms, the Edwardian-era rolling skating craze was bound to be followed by a bust, in its case made inevitable by the advent of the motion pictures. However, that this boom crashed so hard and so fast was due to the greed of men like Chester Parks Crawford, Samuel Winslow, Frederick Arthur Wilkins, and others who treated it as a get-rich-quick scheme. Still, this should not detract from the role that the craze played in the rise of physical recreation and the spread of athletic pursuits, particularly given its openness to women’s as well as men’s competitions.

It is with some irony, then, that the best surviving evidence we have of the skill and athleticism of roller skating’s Edwardian-era stars are the motion pictures of Charlie Chaplin, the first truly global star of the entertainment that replaced it.

Jamie Barras, September 2025.

Back to The Spectacle

Notes

[1] ‘Charlie Chaplin in “The Rink”’, Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly, 26 April 1917.

[2] Karno’s “Rolling Skating” sketch starring Chaplin: ‘The Hippodrome: Karno’s Comedians at the Hippodrome’, Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, 1 February 1910: comedians roller hockey team featuring Chaplin: ‘Comedians in Hockey Match’, Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, 5 February 1910.

[3] ‘Public Notices’, Buchan Observer and East Aberdeenshire Advertiser, 2 November 1909.

[4] The description of the origins of roller skating is taken from the following:

Jack Rundell, ‘The Chaplin Craze: Charlie Chaplin and the Emergence of Mass-Amusement Culture’, PhD thesis, University of York, 2014, 44–62.

Frederick J. Haskin, ‘Roller Skating, Once an American Craze, Is Returning to Popularity After Decline’, El Paso Herald, 7 October 1911.

[5] This will be covered in depth in the article, but, for now, we might cite Chesterfield native Bert Randall, who won cup-winners’ medals in roller hockey and was also a world champion speed and endurance skater in both the UK and US: ‘Chesterfield Roller Skater in America’, Derbyshire Times, 23 September 1933.

[6] ‘A Versatile American’, World’s Fair, 6 January 1912.

[7] Dave Day, Fit for Purpose: The Victorian and Edwardian Athletic Body. The Natural Body Research Seminar, International Centre for Sports History and Culture, De Montfort University, Leicester, 27 April 2012.

[8] See, for example, roller skater Allie Moore, who was said to hold ‘all the world’s records and gold and diamond medals’, ‘Wimbledon Olympia’, Wimbledon and District Gazette and South-Western Times, 29 November 1909.

[9] ‘Rodney Peters Deposits £100’, Sporting Life, 11 December 1909. First National Skating Association championship: ‘Roller Skating’, Sporting Life, 4 February 1909. Second National Skating Association championship, Peters the victor: ‘Roller Skating’, Morning Leader, 28 February 1910. It is worth noting here that this second championship was itself an answer to the challenge laid down by Peters’ manager: ‘A Chance for Speed Men’, Sporting Life, 5 February 1910.

[10] See Note 4 above, second reference.

[11] ‘Advertisements and Notices’, Liverpool Daily Post, 21 November 1872.

[12] Plimpton files lawsuits: ‘Skating on the Pier’, Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 11 March 1876; ‘Rival Roller Skates’, Nottingham Journal, 10 March 1876. Victory for Plimpton: ‘The Plimpton Roller Skate’, Harrogate Herald, 25 April 1877; Britain fails to respond to the revival of roller skating with the first boom in the US: ‘Roller Skating’, Field, 25 April 1885.

[13] For a great guide to the British speed roller skating scene, past and present, see: https://www.britishskatinglegends.com/, accessed 22 August 2025.

[14] ‘The Skate King’, Topeka State Journal (Topeka, Kansas), 23 October 1909.

[15] Crawford’s American adventures and meeting with Winslow: Note 14 above.

[16] First Crawford Rink in Liverpool: ‘Roller Skating at Tournament Hall’, Liverpool Daily Post, 18 November 1907. The story of the American Roller Rink Company: ‘The Court Hears an Echo of the Bygone Rink Boom’, Financial News, 19 March 1912. Example of Crawford and Wilkins hiding behind one of their operating companies to avoid paying bills: ‘A Sheffield Rink’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 22 March 1910. Complex web: ‘Prospectus: The American Skating Rink Co. (Paris) Ltd.’, Hull Daily Mail, 14 July 1909.

[17] Number of rinks by 1910: ‘The Rinking Boom’, Swindon Advertiser, 17 January 1918. American Roller Rinks as a type of rink not just a company name: ‘Rinks in England’, Billboard, 6 August 1910.

[18] ‘Roller-Skating at Olympia’, London Evening Standard, 8 December 1908.

[19] Charles B Cochran and Fun City: ‘Mammoth Fun City’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 23 August 1907. Events at Olympia skating rink: ‘Roller-Skating at Olympia’, Daily Telegraph & Courier (London), 8 December 1908.

[20] ‘Roller-Skating Championship’, Westminster Gazette, 7 January 1909.

[21] History of National Skating Association and Fen Skating: https://web.archive.org/web/20250523023925/https://www.museumofcambridge.org.uk/2021/09/the-history-of-fen-skating/, accessed 22 August 2025.

[22] ‘Roller-Skating Championship’, Daily Mirror, 20 January 1909.

[23] ‘Aviation and Motoring’, Referee, 26 July 1914.

[24] Bio of Davidson assembled from: ‘Skating Champion’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 9 February 1909; ‘Rinking Wrinkles: Skating Champion Interviewed’, Morning Mail (Dublin), 12 November 1909. Information on Davidson and his family can also be gleaned from official records, for example, the entry for H.P. Davidson, 1880 US Federal Census, St Paul, Minnesota, District, and the entry for Harley Payton Davidson, 10 March 1946, in Minnesota, Deaths and Burials, 1835-1990, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 18 August 2025.

[25] See Note 24 above, second reference.

[26] Mabel Davidson: ‘Queen of the Ice’, Penny Illustrated Paper, 12 December 1896; Death: ‘The Death of the Queen of Skaters’, Western Mail, 17 December 1898.

[27] ‘Rinking Gossip’, Era, 27 March 1909.

[28] Moore’s trick skating: ‘The Champion Skater’, Liverpool Echo, 20 February 1909.

[29] ‘Roller Skating Races’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 13 February 1909.

[30] Moore and John Davidson arriving late in the day: ‘Roller Skating: American Champion for England, Sportsman, 9 February 1909; ‘Roller Skating: the £400 Race’, Sportsman, 10 February 1909. Harley Davidson demolishing his Sheffield opposition: Note 28 above.

[31] London Regionals, first heats: ‘Roller Skating: The One-Mile Professional Championship, Sportsman, 24 February 1909; London regionals, semi-finals: ‘Roller Skating: The One Mile Professional Championship, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 25 February 1909. Bill Curtis’s career: https://www.britishskatinglegends.com/british-skating-legends/bill-curtis-(senior), accessed 22 August 2025.

[32] For London regional final, see Note 31 above, second reference. For the winning times of the other regional finals, see ‘Roller Skating’, Sportsman, 25 February 1909. The next fastest heat was the Manchester heat, which was a full 12 seconds slower than the London race; most of the other heats were as much as a minute slower.

[33] Charles Wilson: https://www.britishskatinglegends.com/british-skating-legends/charles-wilson, accessed 22 August 2025.

[34] ‘Roller Skating Champion’, Daily Mirror, 27 February 1909.

[35] Race result: ‘Roller Racing Championship’, Globe, 27 February 1909; and Note 34 above. For Rodney Peters, see Note 9 above.

[36] Moore’s challenge and Davidson’s acceptance: ‘Roller Skating’, Sportsman, 2 March 1909 and 4 March 1909.

[37] John F. Davidson creates International Professional Skaters’ Association: ‘Rinking Gossip’, Era, 27 March 1909; Allie Moore and Harley Davidson founder members: notice, ‘Rinking Gossip’, Era, 17 April 1909.

[38] One mile race at Earls Court: ‘Roller Skating’ Irish Times, 1 April 1909; two mile race at Earls Court: ‘At the Earl’s Court Roller Skating Rink’, Daily News (London), 5 April 1909. One mile races at Manchester: ‘Roller Skating at Old Trafford’, Manchester Courier, 14 May 1909; two mile races at Manchester: ‘Roller Skating at Old Trafford’, Manchester Courier, 15 May 1909; race at Norwich: ‘Rinking Gossip: Moore v. Davidson’, Era, 29 May 1909.

[39] ‘Harley Davidson’s Pupil’, Era, 19 June 1909.

[40] For an overview of public opinion and women athletes in Victorian Britain, see: June Arianna Kennard, ‘Woman, sport and society in Victorian England’, Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education, 1974. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/Kennard_uncg_7422020.PDF, accessed 24 August 2025. The quote comes from page 146.

[41] ‘The “Ideal” Rink’, Blackpool Gazette & Herald, 5 March 1909.

[42] ‘The Roller-Skating Girl’, Fleetwood Chronicle, 22 June 1909.

[43] Quoted in: Mike Fishpool, ‘Miles and Laps: Women’s Cycle Racing in Great Britain at the Turn of the 19th Century’, Playing Pasts, https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/gender-and-sport/miles-and-laps-womens-cycle-racing-in-great-britain-at-the-turn-of-the-19th-century-part-i/, accessed 24 August 2025. For a detailed discussion of women’s cycling in Great Britain in the Victorian era, see Kennard, Chapter VIII, ‘Synthesis of Women’s Sport: The Iron Steed’, Note 40 above, pages 148–166.

[44] ‘Roller Skating’, Bray and South Dublin Herald, 30 October 1909.

[45] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/40293573/nellie-reynolds, accessed 24 August 2025.

[46] ‘The People: Palace Theatre’, Era, 24 July 1909.

[47] Dunedin troupe: https://sheffield.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15847coll3/id/79896/; Maudie Dunedin: https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/dunedin-maudie-c-1888-1937, accessed 24 August 2025.

[48] Dunedins, Nellie the ‘skate dancer’, and Charles Chaplin Sr: ‘Amusements in Leicester: New Tivoli’, Era, 16 December 1893.

[49] This sequence of events can be reconstructed from: ‘Births, Marriages, and Deaths’, Era, 21 April 1900; https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/30837573/william-andree; https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/62216496/maude-lemaire.

[50] Earle Reynolds and Nellie Donegan (note Nellie is referred to as ‘Elsie Donegan’ from Indiana in this article, but it is clearly Nellie Donegan, and there is even an autographed photo accompanying the article that shows this): https://www.skateguardblog.com/2016/02/from-big-top-to-brussels-skating-family.html, accessed 24 August 2025. Earle Reynolds: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/40177873/adams_earle-reynolds, accessed 24 August 2025. In association with John F Davidson’s Professional Skaters’ Association: ‘Mr Earle Reynolds and Miss Donegan’, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 3 April 1909.

[51] ‘The People: Palace Theatre’, Era, 24 July 1909.

[52] It is worth noting here than Nellie’s sister, Maudie, often competed in charity sporting events. Maudie’s best time in the 100-yards dash was 13 seconds: ‘Music Hall Home Sports’, Daily Telegraph & Courier, 29 August 1900.

[53] See Note 24 above, second reference.

[54] Nellie and Earle’s later career and the Hartford Circus Fire: Note 50 above, and https://www.circusfire1944.com/, accessed 24 August 2025. The Reynolds–Donegan act with Maudie and Ellen Andree: ‘Roller-Stunters: A Family on Wheels, at the Palladium’, Sketch, 18 August 1920.

[55] ‘Harley Davidson’s Partner’, Era, 7 August 1909.

[56] See Note 55 above. Compare this to the quote for Donegan, Note 46 above.

[57] See, for example, entry for Harley Davidson and Dolly Mitchell in notice for International Professional Roller Skaters’ Association, Era, 19 June 1909.

[58] ‘Amusements & Exhibitions’, Western Daily Press, 23 May 1910; ‘Public Notices’, Hucknall Morning Star and Advertiser, 7 April 1911. Dolly, her mother, and brother, James Eden Mitchell, are boarding in Bournemouth in at the time of the 1911 England Census: entry for Dolly Mitchell, 1911 England Census, Bournemouth District, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 20 August 2025.

[59] Lillian Franks billing: see Note 57 above. The biography of Lillian Franks and the story of the Franks’ time in Europe and the UK can be assembled from passport applications that they made during their trip: passport application for Mrs Charles L Franks, 9 October 1911, Brussels, Belgium, passport application of Charles L Franks, 9 October 1911, Brussels, Belgium, U.S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925. Lillian’s marriage to Charles Sarnelle/Sannela: entry for Lillian E. Franks, 2 May 1921, New York, New York, U.S., Marriage License Indexes, 1907-2018, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 20 August 2025.

[60] Crawford’s roller skating elephant: ‘Round the Rinks’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 10 March 1903. Performing chimpanzees called Consul: https://travsd.wordpress.com/2013/07/07/stars-of-vaudeville-739-consul-the-great/, accessd 24 August 2025. Consul mechanical calculator toy: Caitlin Donahue Wylie, “What ‘Consul, the Educated Monkey’ Can Teach Us about Early-Twentieth-Century Mathematics, Learning, and Vaudeville.” Chapter. In The Whipple Museum of the History of Science: Objects and Investigations, to Celebrate the 75th Anniversary of R. S. Whipple’s Gift to the University of Cambridge, edited by Joshua Nall, Liba Taub, and Frances Willmoth, 237–56. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. Frank Bostock and Consul: ‘Death of Mr Frank Bostock’, Daily Herald, 9 October 1912. Charles Judge:’Monkeys at the Hippodrome’, Portmouth Evening News, 21 March 1911; ‘Round the Theatres this Week’, Liverpool Echo, 4 May 1937.

[61] ‘Roller Polo’, Morning Leader, 27 February 1900.

[62] Birth of roller polo: ‘Roller Polo’, Aberdeen Evening Express, 5 May 1879.

[63] Dublin roller polo: ‘Dublin Roller Skating Rink: Polo Championship, Season 1895’, Irish Times, 15 January 1895. Circus venue: ‘American Roller Polo: An Exciting Novelty’, To-day, 8 March 1900.

[64] Roller Hockey name: ‘Roller Hockey’, Ottawa Free Press, 3 May 1907. Northern Roller Hockey League: ‘Roller Hockey’, Wigan Examiner, 7 September 1909. Women’s teams in Wigan: ‘Roller Hockey at the Pavilion’, Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, 9 November 1909. Women’s teams in Northampton and London: ‘Ladies’ Roller Hockey’, Northampton Chronicle and Echo, 10 December 1909.

[65] Seven-a-side games in Lanarkshire: ‘Roller Hockey’, Motherwell Times, 12 November 1909. Zoo rink team (Glasgow), and Edinburgh Olympia team: ‘Inter-City at the Zoo’, Scottish Referee, 29 November 1909. Women’s teams in Scotland: ‘Paisley Roller Skating Rink’, Barrhead News, 30 September 1910.

[66] Roller Hockey in Wales: ‘Hockey on Skates’, Aberdare Leader, 22 January 1910. Falkirk, Edinburgh, and Glasgow: ‘Roller Hockey’ Falkirk Herald, 19 March 1910; North-Wesern Roller Hockey League, results and league table: ‘North-Western Roller Hockey League’, Barrow Herald and Furness Advertiser, 15 February 1910.

[67] England vs Ireland: ‘Roller Hockey’, Dublin Daily Express, 25 April 1910. Ulster Roller Hockey Union: Roller Hockey’, Northern Whig, 15 October 1910.

[67i] NHRA changes its name from ‘National Rink Hockey Association’ to ‘National Roller Hockey Association’: ‘Roller Hockey’, Herne Bay Press, 12 December 1930. ‘Rink Hockey Association’, ice hockey: ‘Hockey on the Ice’, Pall Mall Gazette, 31 March 1897.

[68] ‘Rink Collapse At Bradford’, Financial News, 17 February 1910.

[69] ‘The Roller-Skating Craze’, Christchurch Times, 26 February 1910.

[70] ‘At The Pictures: Craze that has Eclipsed Roller Skating’, Blackpool Gazette & Herald, 23 September 1910. Montagu Pyke: Luke McKernan, “Diverting Time: London’s Cinemas and Their Audiences, 1906–1914.” The London Journal, 2007, 32 (2), 125—44. doi:10.1179/174963207X205707.

[71] Sheffield Rink failure: ‘A Sheffield Rink’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 22 March 1910; Bradford: Note 68 above. Leeds: ‘Skating Rinks Closed in Leeds and Bradford’, Bradford Observer, 15 February 1910. Aberdeen Rink Failure: ‘Roller-Skating Dispute’, Financial News, 12 February 1913.

[72] Investors looking for their money: ‘Rink Collapse in Bradford’, Bradford Daily Argus, 14 February 1910. Final Verdict: ‘Maningham Skating Rink’, Bradford Daily Argus, 26 February 1910.

[73] See Note 16, second reference, and Note 17, second reference.

[74] See Note 16, second reference.

[75] Note 71 above, final reference, and ‘Roller-Skating Dispute’, Financial News, 13 February 1913.

[76] ‘Collapse of Rink Boom’, Financial News, 7 June 1917.

[77] https://www.culvercityhistoricalsociety.org/historic-sites/site14/, accessed 24 August 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104273133/chester_park-crawford, accessed 24 August 2025.

[78] See Note 5 above.

[79] https://www.rollerskatingmuseum.org/roller-hockey, accessed 25 August 2025.

[80] https://www.sportshistoryweekly.com/stories/rollerblading-inline-skating-x-games-recreational-sports,1104, accessed 25 August 2025.

Poster, The Rink, Mutual Pictures, 1916. Public domain.

Charlie Chaplin starring in Fred Karno's Rollerr Skating sketch, 1910. Sheffield Evening Telegraph, 22 February 1910. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Harley Davidson, speed skater. Los Angeles Herald, 18 March 1906. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Harley Davidson, ready to race. Era, 13 February 1909. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Ice Skating Carnival, Lady's Pictorial, 10 April 1897. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Mabel Davidson, Queen of the Ice. Penny Illustrated Paper, 12 December 1896. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Allie Moore, speed skater. Era, 27 March 1909. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Nellie Donegan, 'fancy' skater and trick cyclist. Illustrated Police Budget, 21 August 1909. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

'Baby' Lillian Franks, child skater. Scottish Referee, 19 July 1909.

American Roller Polo. To-day, 8 March 1900. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

League table, North-Western Roller Hockey League. Barrow-in-Furness Herald, 15 February 1910. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Olympia Roller Rink, Wakefield. Postcard. Author's own collection.

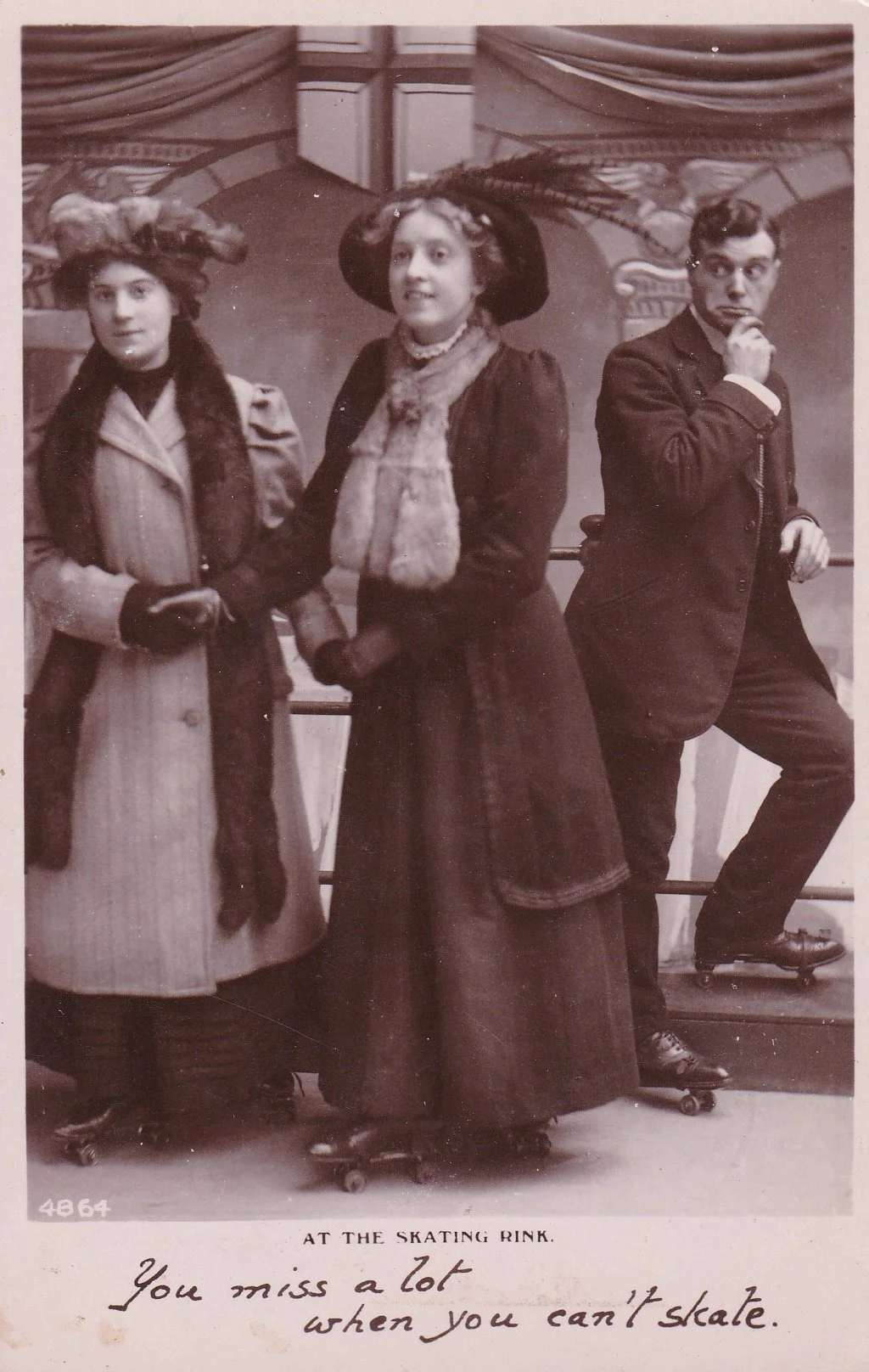

Edwardian Roller Skating Humour. Postcard, author's own collection.