The Jūjutsu Waltz

Jamie Barras

WHAT EVERY WOMAN SHOULD KNOW." Strenuous Realism in Ju-Jitsu Playlet. WIFE'S REMEDY. “What Every Woman Ought to Know" is the suffragette playlet which has been performed in East London with great success, and will be seen in the West End of London before Easter. Probably Mr. Martyn Roland and Miss Eva Quin will give a private performance for the rebellious suffragettes on census night. But so extremely energetic is the action that they have to rehearse it every day to keep in training, and the Daily Mirror yesterday witnessed a rehearsal at Mrs. Garrud’s ju-jitsu school in Argyll-place, W. Bill Borrer, a coster, and his wife Eliza are the two principal characters, and the playlet shows his reformation by ju-jitsu, or, as he puts it—“this ‘ere juicy-jujubes.”[1]

The story of the adoption of jūjutsu (柔術 aka ‘ju-jitsu’) by the women’s suffrage movement in Britain is well known, as is that of its chief proponent, Edith Garrud (1872–1971), who, in 1913, founded the much-storied ‘Bodyguard Unit’ of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the members of which employed Indian clubs, truncheons, and their knowledge of jūjutsu to combat police attempts to arrest Emmeline Pankhurst, most obviously in the ‘Battle of Glasgow’ of 9 March 1914.[2] Equally well known are the stories of Sadakazu Uyenishi (上西貞一, Uenishi Sadakazu (1880–?)), Yukio Tani (谷幸雄, Tani Yukio (1881–1950)) and Taro Miyake (三宅太郎,Miyake Taruji (1881–1935)), three [male] Japanese jujutsu masters who, while teaching in Britain, supplemented their income by going on the music hall stage to perform exhibition matches and take on all-comers. Garrud and her husband, William, learned their jūjutsu under Uyenishi and took over his studio after he returned to Japan in 1908.[3]

Here, I want to focus on the less-well-known story of the use of jūjutsu by stage acts featuring women, either in partnership with men or alongside other women, showcasing the way in which the chief attraction of the technique to teachers of women’s self-defence, its ability to allow smaller, ‘weaker’, combatants to best larger, ‘stronger’ opponents, was used to subvert traditional male and female roles in the arts, particularly couple dances, to entertaining effect. In this, I am making a distinction between subverting roles and swapping roles—this is not the story of female performers who took on roles usually associated, at least in the minds of the theatregoing public, with men, for example, stage magicians such as Adelaide Herrmann and Vonetta, or sharpshooters like Annie Oakley and Rifle Nell Swallow. Nor is it the story of male impersonators like Vesta Tilley and every best boy in every pantomime ever.[4] It does, however, begin with a pantomime.

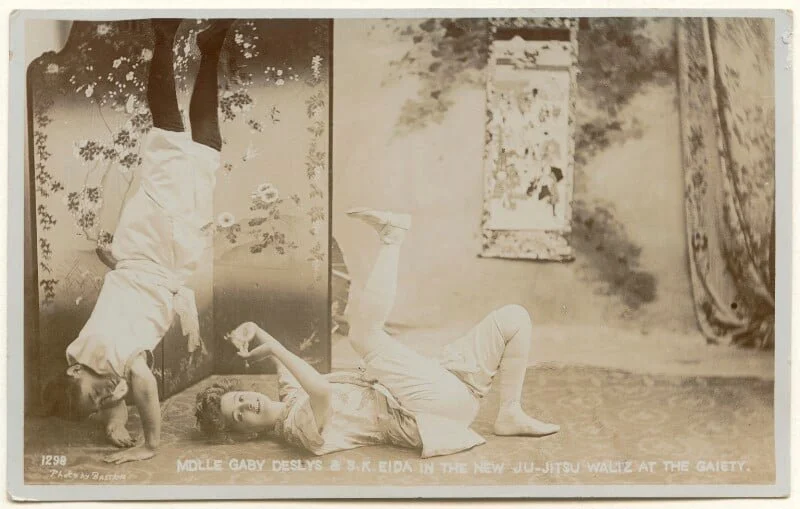

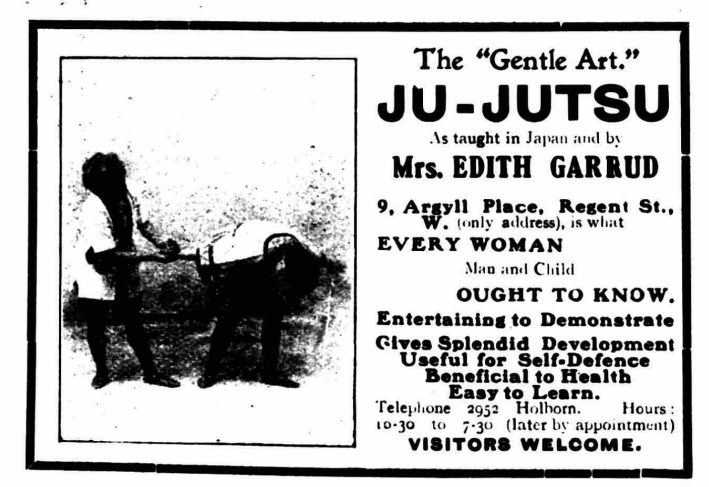

Mr. Edmund Payne, who has been out of the cast of "The New Aladdin " at the Gaiety for several days on account of ill health, returned last night, when an additional feature was added to the play, being "Ju-Jitsu" song and dance by Mlle. Gaby Deslys, assisted by S. K. Eida, of the Japanese School of Ju-Jitsu, which went remarkably well, and was warmly applauded.[5]

In the strictest terms, ‘The New Aladdin’ was not a pantomime, but a book musical. Produced by George Edwardes for his Gaiety Theatre,[6] it was aimed squarely at an adult, not family audience, the latest in a long line of the signature Gaiety musical comedies with music by Lionel Monckton and Ivan Caryll. However, as its title suggests, it borrowed its plot, characters, and structure from the pantomime staple and even featured an actress in a trouser role playing the male lead. A pantomime for adults.[7]

‘The New Aladdin’ opened at the Gaiety in October 1906, and one of the more overtly ‘adult’ elements of the show was the character song, ‘Sur Le Plage’, featuring lyrics like ‘When I take my bain-de-mer/At what do all the men stare?’, performed ‘in a rather daring bathing costume’ by 25-year-old French actress Gaby Deslys (Marie-Elise-Gabrielle Caire, 1881–1920).[8] Deslys, regarded as one of the most beautiful women of the age, made her London debut in ‘The New Aladdin’ and would go on to conquer Britain and America and amass a fortune. She would, however, die young, contracting Spanish Flu in 1918 and dying two years later, aged just 38, of complications arising from throat abscesses caused by the disease. She left her fortune to the poor of her hometown of Marseilles.[9]

‘The New Aladdin’ was not the success that Edwardes had hoped it would be, tending as it did more to the burlesque than the usual Gaiety fare. In February 1907, Edwardes, recognising that Deslys at least had made a favourable impression on audiences, added a new number for the actress that took advantage of her physicality rather than her physique: the ‘Ju-Jitsu Waltz’. In a piece lavishly illustrated with photographs showing the act, The Sketch magazine claimed that it was based on a new dance recently introduced in Berlin by the ‘Sisters Dejo’.

Erich Rahn opened the first jūjutsu school in Berlin in 1906, which would be consistent with the timing of the Dejo sisters' act. Interestingly, from our perspective, one of men who taught Rahn jūjutsu was Akitaro Ono (大野秋太郎, Ono Akitaro (1876–1942)). Ono was active throughout Europe and North and South America in this period, including teaching alongside Sadukazu Uyenishi in London for a time when the Garruds were Uyenishi’s students. In 1906, Ono travelled to Berlin to teach jūjutsu to the German military. However, by the autumn, he was back in London teaching at the Polytechnic Y.M.C.A. His later activities in England included wrestling under the name ‘Daibatsu’ in matches promoted by William Bankier, whom we will meet shortly.[10]

The Dejo Sisters are identifiable under that name from German sources, principally postcards printed at the time with their photographs, but little else is known about them, other than that one of the sisters was named ‘Lilly’. It is worth noting that there was a dancer with the stage name ‘Deyo’ active in Europe in this period, and ‘Deyo’ might be read as ‘Dejo’ in German. Deyo’s real name was Blanche Lillian Pixley, an American, and in the latter part of her career, she used the stage name Blanche Lillian Deyo. We might speculate, therefore, that the ‘Dejo Sisters’ were Blanche Deyo/Pixley and another dancer. However, there are two problems with this hypothesis: 1) there is little physical resemblance between photos of Lilly Dejo and Blanche Lillian Deyo; and 2) Blanche Deyo was active on the Broadway stage throughout 1906. We are left to suppose that either it was simply coincidental that Lilly Dejo and Blanche Lillian Deyo were two dancers with very similar stage names when spoken in German active in the same period, or that there was some element of, let's be generous and call it, ‘homage’ involved in the choice of the Dejo Sisters’ stage names.[11]

While the Dejo Sisters, whoever they were, were real, and they do appear to have introduced a dance they called the ‘ju-jitsu waltz’ that included ‘various ju-jitsu holds, locks, and other actions’ into their variety act, one only needs compare photographs of the Dejo sisters dancing to those of Gaby Deslys throwing her partner around on stage to see that, if the Gaiety act took anything at all from the Dejo Sisters routine, it was only the name.

The partner that Gaby Deslys was throwing around on stage, identified as ‘S.K. Eida’ in the quote above, was Kanagawa native Suyekichi Iida (飯田末吉, Iida Suyekichi, 1881–1918), an assistant instructor of jūjutsu at the ‘Japanese School of Jui-Jitsu’ on Oxford Street, which had been opened in 1904 by Yukio Tani and Taro Miyake, the jūjutsu masters and sometime music-hall performers. Another of the assistant instructors at the School was Phoebe Roberts (1887–1936), second only to Garrud in terms of female jūjutsu teachers in Britain in this period. We will meet Ms Roberts again later. Iida had travelled to England to live with his older brother Saburo, an art importer and garden designer.[12]

Although we cannot be sure where Gaby Deslys received her initial instruction in jūjutsu, we do know that, once the act debuted, she rehearsed daily at the Gaiety, possibly with Yukio Tani himself (this information comes in the form of the recollections of the Gaiety stage door manager nearly 20 years later; it is possible that he meant Iida).[13]

So, where did the idea for the Gaiety act come from? The simplest answer is that it was inspired by the Dejo Sisters’ act, or at least the idea behind it. Edwardes, or someone in ‘The New Aladdin’ creative team (Harry Gratton, the show’s choreographer?[14]), could have seen newspaper reports about the Dejo Sisters’ act and reached out to Tani or Miyake, or their British manager, music hall strongman William Bankier, aka ‘Apollo, the Scottish Hercules’, to help them create their own version of it. If this is the case, then Bankier would have had his own contribution to make to the form it would take, as a few months before the Gaiety act debuted, he had himself appeared on stage in an act with a female jūjutsu practitioner.

THE HIPPODROME.—Apart from its association with our allies in the Far East, ju-jitsu possesses inherent merits which render its popularity quite intelligible. A knowledge of its practice certainly adds to one’s powers of personal defence, and this was clearly and most interestingly demonstrated last night at the Hippodrome by that skilled athlete Apollo and Miss Moya Sam, a Japanese champion of the art. Attacked by men unexpectedly, Apollo, by the display of ju-jitsu, speedily placed his assailants hors de combat, and the Japanese lady also showed that any footpad molesting her would also come off rather badly in the personal encounter.[15]

‘Moya Sam’ is almost certainly Maud Omoyo Kurakami (1889–1971) (‘O’ (お) is a Japanese prefix that was, in the past, routinely added as an honorific to women’s given names[16]). Omoyo Kurakami was the daughter of Japanese acrobat Kumakichi Murakami and his English wife, Hannah Storey, and had performed alongside her father and siblings from a young age. As ever, I am indebted to Pernille Rudlin, curator of the Digital Museum of Japan-UK Showbusiness, for information regarding Japanese acrobatic troupes in Britain in this period.[17] We can be confident of this identification as, within a few months, Omoyo Kurakami would be back on stage performing an identical act alongside a new partner, her future husband, Frank Long—something that would incur Bankier’s ire. We will return to Omoyo Kurakami and Frank Long later.

Although the Bankier–Moya act did not include any dancing—it was simply a version of the act performed by Yukio Tani, Taro Miyaki, and others, with the inclusion of a female jūjutsu practitioner—Bankier would have seen how well the audience took to seeing a woman throwing a man about the stage. Did Edwardes approach Bankier about reproducing the Dejo Sisters’ dance act, and did Bankier suggest something more vigorous based on his experience of audience reactions to ‘Moya Sam’? We cannot know; however, it is clear from the photographs of Gaby Deslys and Suyekichi Iida in The Sketch that it was centred on Gaby Deslys making use of her newfound knowledge of jūjutsu to send Iida flying as often and in as many interesting ways as possible.

Those photographs, and others in the series, all credited to the Bassano Ltd studio, are our best guide to what form not only the Deslys–Iida act took but also acts that followed it. The first thing to note is the ‘costumes’ worn by the pair. Iida is wearing the style of gi (衣) favoured by the jūjutsu schools in London of the period, a short-sleeved white jacket (上衣, uwagi) secured with a white belt (帯, obi) over white pants (下穿き, shitabaki) bound with black leggings.[18] The short uwagi and black leggings were peculiar to the Edwardian period, and obi of different colours to denote rank were a later innovation. As an aside: the role that the wearing of the gi may have played in weighing challenge matches against wrestlers schooled in bare-chested European styles in favour of jūjutsu exponents is a fascinating one.[19]

Deslys, meanwhile, is, as might be expected, wearing something much more richly patterned and of finer material, although of basically the same cut and composition, with the exception that, in common with gi for women in this period, the obi was much more like a sash than a belt and the shibataki and leggings were replaced by bloomers over tights. It is also worth noting that Deslys is displaying more décolleté than was usual for women practitioners of jūjutsu in this period. At what do all the men stare? indeed.[20]

As these are photographs and, of course, selected to highlight the more spectacular moments of the choreography, we can only guess at how close to a ‘waltz’ the non-throwing moments of the dance were. We can suppose, just from the perspective of stamina, there were ‘slow’ moments in the routine, which probably involved some of the ‘holds, locks, and other actions’ employed by the Dejo Sisters in their act. These would also allow Deslys and Iida to position themselves correctly, both relative to each other and relative to the footlights and other hazards for the next throw. What the photographs do make clear is that Deslys is the dominant partner; however, critically, this is in the form of a woman, a very feminine woman, taking the lead over her male and masculine partner, not as a woman assuming the role of the man, and by extension, her male partner assuming the role of the woman, in an otherwise traditional couple dance. This is not male/female impersonation; it is something different and new, a woman asserting her equal status with a man by virtue of her physicality and acquired skills. It is worth noting that, while in London, Gaby Deslys was also photographed sitting behind the wheel of a motor car.[21]

(It should also be added that, while this specific case might be mistaken for an example of the Western feminisation of East Asian men,[22] as the quote that opens this piece shows, and as we will see below, couple-based jūjutsu acts on the English stage more often than not, for obvious demographic reasons, featured men of European heritage being bested by jūjutsu-trained female opponents—that Iida was East Asian was incidental.)

Eida and Falco, in a new Japanese ju-jitsu, vocal and dancing speciality, prove instructive, showing how a knowledge of jujitsu methods enables a lady to defend herself against attack by a man relying on physical strength.[23]

Alas, the ‘Ju-Jitsu Waltz’, for all its popularity, was not enough to save ‘The New Aladdin’, which closed in April 1907. Gaby Deslys quickly went on to bigger and better things. Meanwhile, within a few months, Iida would be touring the halls with an act inspired by, if not directly copied from, his turn with Deslys. For this, he had a new partner, Nellie Falco, the stage name of Ellen Christina Brown (1886–1931), who, in February 1909, would become Iida’s wife. As Falco and Eida, the pair would tour their ‘ju-jitsu dancing’ act around the halls until December 1913.[24]

Meanwhile, back in December 1906, William Bankier’s former stage partner, ‘Moya Sam’/Omoyo Murakami, had returned to the stage with her new partner, and future husband, Francis William ‘Frank’ Long (1887–1959),[25] and a pupil of Long’s dubbed ‘Ajax, the Pocket Hercules’.

There is a very attractive bill of fare this week, the leading turn being Omoya San and company as exponents of ju jitsu. The three artists, Professor Long, Ajax, and Miss Omoyo San, are adepts and their displays consist of exhibitions and explanations of the various uses of the Japanese art of self defence.[26]

It is interesting to note that the company bore Omoyo Murakami’s name. It would be nice to believe that this was because it was her company; however, while this is certainly possible, it seems more likely, given the times and that Omoyo Murakami was only 16 or 17 in 1906, that this was simply clever marketing, using a Japanese name to lend more authenticity to the jūjutsu on display.

Frank Long was an Islington native who, since at least 1902, had served as a gymnastics instructor at the St Gabriel’s Amateur Gymnastics Club in Cricklewood. While there, he provided instruction to members of the Royal Navy Reserve in the use of Indian clubs and parallel bars for physical exercise. He would later claim to have taught jūjutsu to both the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Royal Navy. However, it seems that he, in fact, came into contact with jūjutsu for the first time only in April 1906, which is when St Gabriel’s hosted an exhibition of jūjutsu by two Japanese practitioners, ‘Messrs. Y. Kato and Y. Ogita’. Long became a pupil of William Bankier, probably very shortly after the visit of Kato and Ogita to St Gabriel’s, which is how he came to meet Omoyo Murakami. It is possible he also played a role (one of the assailants?) in the Bankier–Moya Sam act of September 1906.[27]

The latter suggestion is supported by the more detailed description of the Omoyo Troupe act given a few months after it debuted, which made clear that the act was modelled directly on the Bankier–Moya Sam act of September 1906.

Never has a display of ju-jitsu been made more entertaining and instructive in Sunderland than it is in the act of Mr Frank Long, British champion of the world, and Miss [Omoyo] San, woman champion of the world, who are assisted by Ajax, the miniature Hercules. Both Mr Long and Miss San show how street hooligans should be treated, while the gentleman tells the audience the methods they adopt to disable the [assailant]. Besides, the lady and gentleman challenge the world to wrestle them.[28]

The right of Frank Long and Omoyo Murakami to call themselves ‘champions of the world’ is extremely doubtful. However, Frank Long did become the English champion in March 1908—albeit in disputed circumstances: his chief rival, Petty Officer Paul Bradley Mihalop (1881–1951), later of the Royal Navy School of Physical Training, was barred from competing for supposedly being too late to submit his entry form, something that Mihalop disputed vehemently. We can rightly suspect, as Mihalop did, that money changed hands.[29]

The Longs would marry in December 1907; by this time, Omoyo was already pregnant with the couple’s only child, Patricia, who would be born in March 1908. This timing is interesting because ‘Omoyo’ continued to be billed to perform all the way up to the end of March 1908 and was back on stage by mid-May. That there was a gap around the time of baby Patricia’s birth does suggest that this was Omoyo Murakami and not a stand-in: did she simply not perform in late March, although billed to appear? Even if this were the case, it makes one wonder how vigorously she performed in the months leading up to and following Patricia’s birth.[30]

Of additional interest to us here, May 1908 was also the month that ‘Miss Roberts’ issued a challenge to Omoyo via her manager, John G. Payton.[31] Omoyo declined the challenge due to ‘illness’, for obvious reasons, given the timing. ‘Miss Roberts’ was Phoebe Roberts, the now-former assistant instructor at the London School of Ju-Jitsu, which shuttered its doors in 1908. In the summer of 1908, Roberts joined her husband, fellow former assistant at the London School, Yuzo Hirano, on stage in an act that mirrored that of Long and Omoyo, hence the rivalry. This rivalry may also have been stirred by William Bankier, Omoyo’s former professional partner and Frank Long’s former teacher, who employed Roberts to teach female students jūjutsu at his athletic ‘academy’ in Great Newport Street after the shuttering of the London School.[32]

Frank Long and Omoyo Murakami would retire from the stage in December 1908,[33] while Phoebe Roberts and Yuzo Hirano would only briefly perform together in the summer of that year. But to take a step back for a moment, there were, in mid-1908, three Anglo-Japanese couples touring British halls performing jūjutsu acts that pitted men against women, although only the Falco–Iida act had a dancing element. To this tally, we can add another husband-and-wife act that had been around since the autumn of 1907 and would continue until at least 1922—by far the longest-lasting of all the acts we are looking at here, that of Sheffield natives John Enzer (1868–1932) ‘the soldier juggler and sword expert’ and his partner ‘Miss Clarice, the lady ju-jitsu expert’.

Enzer was a 21-year Army veteran and former gymnastics instructor, much like Frank Long. He studied jūjutsu under Yukio Tani and briefly performed his own jūjutsu act before switching to juggling ‘swords and cannonballs’ and leaving the jūjutsu to ‘Miss Clarice’. The identity of ‘Miss Clarice’ is a vexing one. She is described in newspaper reports as Enzer’s wife. Enzer was married to Johanna Enzer née Doyle (1869–1961), and, as the couple had a daughter, Clarice Maud Enzer, born 1900, it would seem reasonable to assume that ‘Miss Clarice’ was Johanna Enzer using her daughter’s name as a stage name. However, here we meet a problem. The 1911 England Census returns for the Enzer family show Johanna Enzer living in the family home in Scarborough with two of the Enzer children, Maud, 11, (i.e., Clarice Maud, born 1900) and Eileen, 13; meanwhile, John Enzer ‘variety artist’, 42, is in digs in Southport with his son, Jack, 17, also, evidently part of the act, and someone identified in the return as ‘Clarice Maud Enzer’, 26, married, ‘variety artist’. What are we to make of this? ‘Clarice Maud Enzer’, 26, is clearly ‘Miss Clarice’, John Enzer’s professional partner, but why does she have the same name as John and Johanna Enzer’s 10-year-old daughter, and why do people think that she and John Enzer are married?[34]

Moving on. Although at first glance, the Enzer–Miss Clarice act would appear to be picking up the baton from the Longs and Phoebe Roberts and Hirano, the juggling element makes it plain that this act was instead pure entertainment, not an attempt to popularise jūjutsu. In this regard, one might suspect that the act depended more on John Enzer’s ability to somersault than Miss Clarice’s ability to throw him. On that point, it is worth taking a moment to jump ahead in the timeline and 11,000 miles in distance to New Zealand in 1915.

Four new imported acts will be introduced, conspicuous among whom will be Gardiner and Lemar, a pair of Ju-Jitsu experts, who will submit their original athletic specialty, “The Hooligan and the Lady”, in which is shown how it is possible for a lady with a knowledge of ju-jitsu to protect herself from ruffianly attacks. Miss Florence Lemar is stated to be the world’s lady ju-jitsu champion.[35]

Husband-and-wife team Joe Gardiner and Florence LeMar, although active in New Zealand rather than England, are worth examining because, unique among the various pairings we have covered, they produced a book that included photographs demonstrating the jūjutsu techniques that a woman might adopt in combating a male assailant. The book in question, ‘The Life and Adventures of Miss Florence LeMar, the World's Famous Ju-Jitsu Girl’, first self-published in 1913, was, as its title suggests, more fiction than fact. It is telling in this regard that, in a modern, knowledgeable review in the Journal of Many Arts, author and martial arts expert, Tony Wolf, noted that ‘It has to be said that, even allowing for the limitations of studio photography at the time, Flossie does not really appear to have been an expert in the art. She frequently seems out of balance and/or effective distance, and the impression is that Joe made full use of his acrobatic skill to "sell" his role as the hapless attacker. In fact, the reader could be forgiven for wondering whether even Joe had much practical knowledge of Jiujitsu’.[36]

One suspects the same could be said of Enzer and Miss Clarice. However, this is not to deride the physicality or skill of the pair, particularly as they performed the same routines, at least in John Enzer’s case, into his fifties.[37]

Continuing this detour into the world of pure entertainment for a moment, alongside the four husband-and-wife jūjutsu acts active in England in 1908, we can add an all-female, all-singing, all-dancing act with its own take on the jūjutsu dance: Kennedy’s Kiddies.

Kennedy's Kiddies proved an extremely interesting performance, in which they introduce dancing and a number of songs, including Some Day We'll Go Back Home," written and composed by Phil (Arthur) Kennedy. The Kiddies also illustrate [a] ju-jitsu dance and well merit the applause they receive.[38]

Kennedy’s Kiddies was a juvenile act comprising ‘a dozen pretty maidens’ under the management of Phil Kennedy, aka ‘Mr. Arthur Kennedy M.A.’, who was also their songwriter and choreographer. Formed in the summer of 1908, the troupe would change its name to ‘The Kennedy Girls’ the following year. Phil Kennedy would rather grandly claim to have ‘invented’ the jūjutsu dance, but it was, of course, a steal from Falco and Iida, if not Iida and Deslys, in at least concept if not also content.[39]

As the members of the Kennedy troupe were all children and all female, this somewhat counterintuitively robbed the jūjutsu dance of much of its feminist undertones, which were, of course, largely rooted in the image of a woman besting a male partner/opponent using technique, not physical strength. This said, by the summer of 1909, one of the troupe’s members, Lily Russell, billed as the ‘lady champion ju-jitsu exponent’, was also performing a solo act, taking on other girls in wrestling or jūjutsu matches before the main Kennedy Girls performance, which at least leaned more into the girls and women learning jūjutsu for self-defence message of women’s rights activists like Edith Garrud.[40]

The Kennedy Girls would keep the jūjutsu dance in their repertoire until the autumn of 1910, after which the troupe went on hiatus. In the spring of 1912, the troupe re-emerged with a new repertoire and, given that it was still billed as a juvenile troupe, perhaps a new line-up, but disbanded shortly afterwards.[41]

The year 1910 is a particularly significant one in terms of the Japanese presence in England and the interaction of British people with Japanese culture, as this was the year that the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition was held at White City in West London.[42]

Among the interesting features of "Tokyo Town," the Japanese quarter of the exhibition, are theatres and places where exhibitions of Japanese swordsmanship, wrestling, and ju-jitsu are being shown daily.[43]

At once a trade fair and a display of elements of Japanese culture, history, and entertainment, the exhibition was held from May to October 1910. Hundreds of performers and artisans were brought over from Japan and installed in purpose-built pavilions and reproductions of traditional Japanese buildings and gardens, and even townscapes.[44] Displays ranged from the latest products of Japan’s growing industrial sector to fine art, both traditional and modern (i.e., European in style), and ancient artifacts. There were daily performances of historical tableau telling the story of Japan, alongside sumo wrestling—a sensation, not least because the rikishi (力士) performed near-naked—and variety acts, particularly jugglers and acrobats. Of interest to us, there were also demonstrations of kendō and jūjutsu, with the latter including, on at least one occasion, a woman in European dress defending herself against male attackers.[45]

However, the real interest of this event from the perspective of this survey is that it also attracted independent Japanese performers to Britain who took advantage of the interest in Japanese culture and life that the exhibition excited in the British public to tour their acts around the halls. The most remarkable of these, not least because it was captured on film, is the act performed, at least initially, by two Japanese actors identified in their publicity as ‘Udagawa’ and ‘Kawamoura’, an act that included elements of jūjutsu in its climax. In the second (or third, if you count the film) version of the performance, Kawamoura’s name was replaced in the billing by that of ‘Miss Namiko’.

“The Punishment of the Samurai” was one of the most dramatic stories in animated photography we have seen. An old man is murdered in Japan, and his daughter determines to be avenged; she attires herself in the robes of a Samurai lady, and on meeting her father’s murderer attacks him, and after a terrible fight, kills him with his own sword. The display of ju-jitsu fighting in this was great, and the picture, which was beautifully coloured, was deservedly applauded.[46]

In fact¸ Le Châtiment du Samouraï, as the title was in the original French, features a young man who dresses as a woman to avenge his murdered father; however, in light of the introduction of ‘Miss Namiko’ into the stage version of the story, this error made by a British newspaper is an interesting one. The film was shot by the Pathe Frères company in France in the Spring or early summer of 1910 and released there and around the world in July of that year, at the height of the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition. We are extraordinarily lucky to have a copy of the full, 8-minute film preserved at the Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, which has made a copy available to view online.[47]

All four roles in the film, and the later stage version of the piece, are played by two Japanese actors, billed as Udagawa and Kawam(o)ura. Based on elements of his performance in the film, not least the donning of female disguise, it seems reasonable to me to suppose that the younger of the two actors, identified as Kawamura, was an onnagata (女方), a male performer of female roles in the all-male Kabuki theatre tradition.

Based on an interview that Udagawa, the older of the two actors, gave to a British newspaper,[48] it seems that the two men were in Europe to study Western acting styles and stage production—which is interesting given that the Imperial Theatre (帝国劇場, Teikoku Gekijō, aka Teigeki, 帝劇), which would feature a Western-style auditorium and Western-style productions, was at the time in the process of being built in Tokyo. Indeed, Udagawa and Kawamura were described as actors from the ‘Imperial Theatre, Tokio’ in the marketing of the film.[49i]

This is significant, as one of the founding members of the Imperial Theatre was a Japanese actor and manager well known to French audiences: Otojirō Kawakami, husband of the actress known in the West as Sada Yacco. The Kawakamis had first appeared in France in 1900 as part of the Paris Exposition and had returned to great success several times after that, including in 1908. Consulting a programme for performances given by the troupe during their 1908 tour, we find amongst the actors the names Udagawa and Kawamura. What’s more, as Kawamura plays a maiko, an apprentice geisha, in one of the plays, we can identify him as an onnagata. Thus, it seems reasonable that Udagawa and Kawamura of 1910 were the Udagawa and Kawamura of 1908 who had returned to France on the instructions of Otojirō Kawakami to study Western theatrical arts for the new Imperial Theatre in Tokyo.[49ii]

By the time that Le Châtiment du Samouraï opened in cinemas (as ‘The Punishment of the Samurai’ in English-speaking countries), Udagawa and Kawamura were in London, taking advantage of interest in the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition, to present a stage version of the piece, retitled ‘Vengeance’.

Udagawa first made his appearance in a forest of dark trees as a weary "old Adam"—but a much less wearisome “old Adam" than we are accustomed to. His son (played by Kawamoura) fell asleep under the eye of the audience; the old man, for protean purposes, took himself to a soft spot out of sight—that he might, as a ferocious brigand of the forest, stride on and murder his former self and steal his former self’s money.[50]

We shouldn’t be surprised that the marketing of the stage version of the story made no mention of the fact that there was simultaneously a screen version touring the picture palaces—the two pieces were essentially in competition with each other. (In this light, one has to wonder what the distributors of the film thought of its actors performing the work on stage.) It is also worth mentioning that there was no mention of any direct connection with the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition. As stated above, Udagawa claimed the two actors were in Europe on other business. This is supported by the fact that the tour of the English and Welsh halls that followed the piece’s London premiere took place while the Exhibition was running. Whether Udagawa’s story about studying European theatre techniques was true or not, it seems clear that the two actors were not performers brought over from Japan to appear at the Exhibition.[51]

As we might suppose from the fact that the two actors were able to take the piece on tour, it was well-received on its London premiere.

No word is spoken, but the subtle and vigorous acting of Udagawa in his three successive character studies of father, assassin, and servant make it perfectly easy to follow the meaning. From the very first, in the midst of peaceful scenery, his feline, writhing, and at the same time rhythmic energy begins to communicate itself to an audience thoroughly hardened to more robust thrills. The son, too, played by Kawamoura, is almost equally adroit, not only in expressing every nuance of emotion but also in suggesting unseen action, whether it is supposed to take place quite near at hand or in the far distance.[52]

The climactic confrontation between the son played by Kawamura and the assassin played by Udagawa, which, as will be remembered, and as can be seen from the Pathe Frères film, featured both swordplay and jūjutsu, was singled out for particular praise as something not seen before on the London stage.

The fight that follows is also something new in the endless annals of stage combat. One does not laugh at it as one laughs at “supers” trying to avoid hurting each other’s ankles, for there is something almost uncanny in this exhaustion of hatred, as though, even in a London music-hall, Japan were able to add a new shudder to the idea of “Vengeance.”[53]

The final performance of ‘Vengeance’ billed as being performed by Udagawa and Kawamura took place in Birmingham at the end of October 1910, coincidentally (?), just as the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition was closing in London. However—and significantly for this survey—that was not the final performance of the work. Instead, it reappeared on the bill of the Hippodrome in London in the middle of the following month, this time as a work performed by Udagawa and ‘Miss Namiko’.[54]

But a couple of complete novelties that should be seen this week are the Japanese one-act drama in dumb-show—“Vengeance”—and the illustration of Australian bushlife which is given by Mr. Fred Lindsay. In the former of these numbers an extremely realistic sketch of crime, profanity, and retribution is hymned by Udagawa and Miss Namiko, with a coadjutor and a shrine.[55]

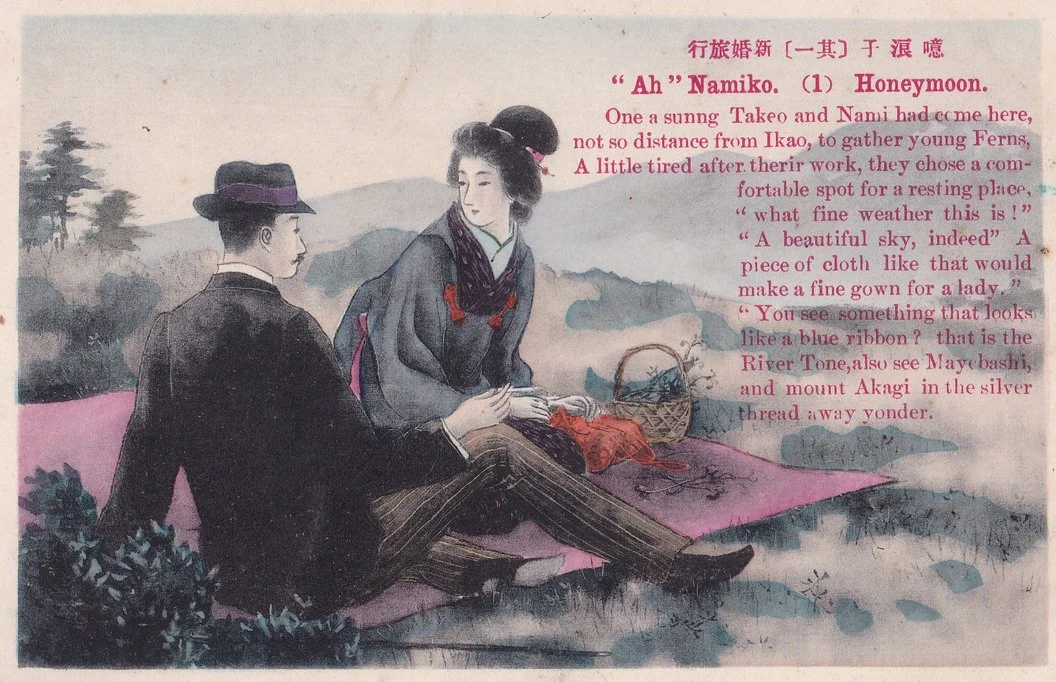

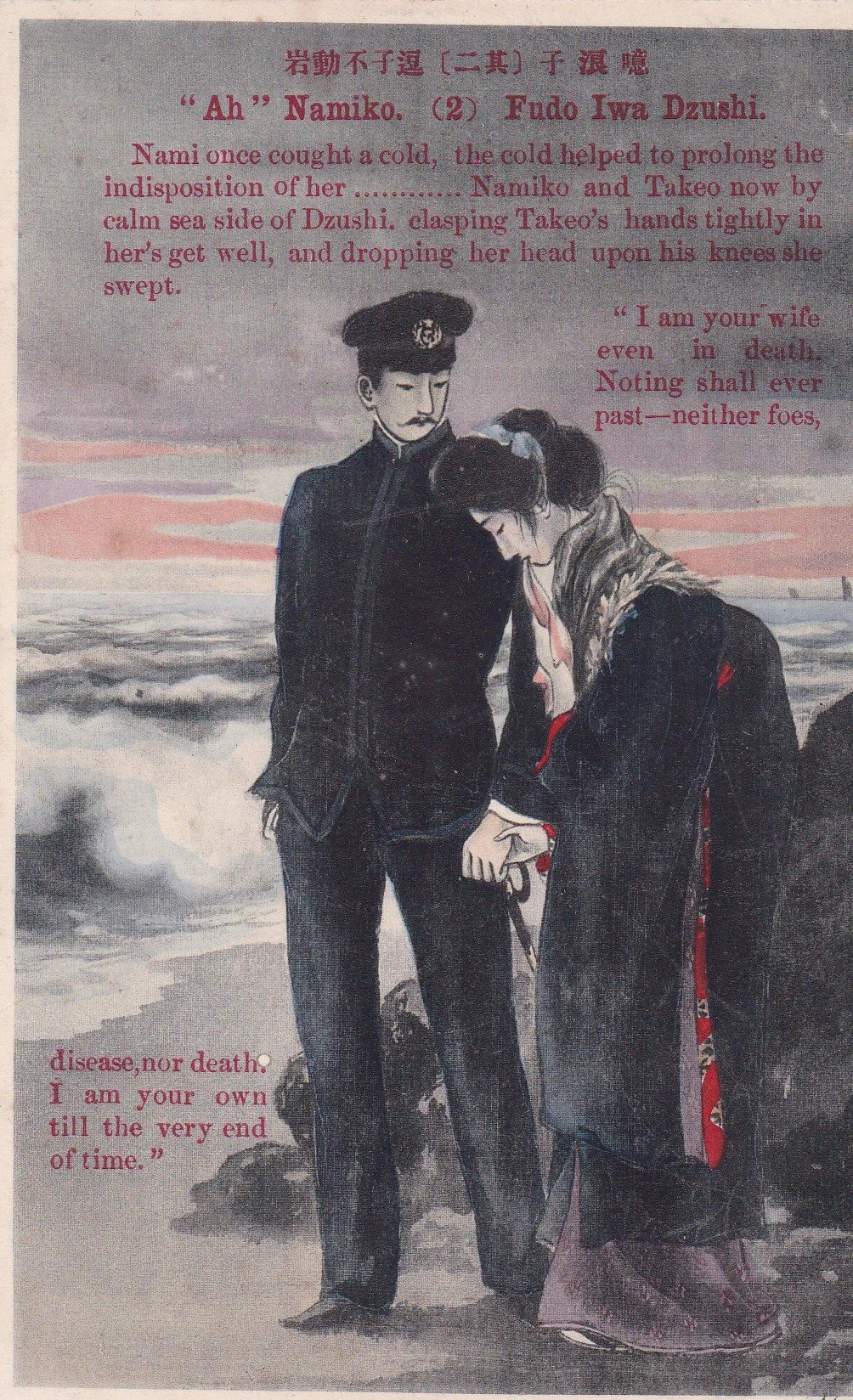

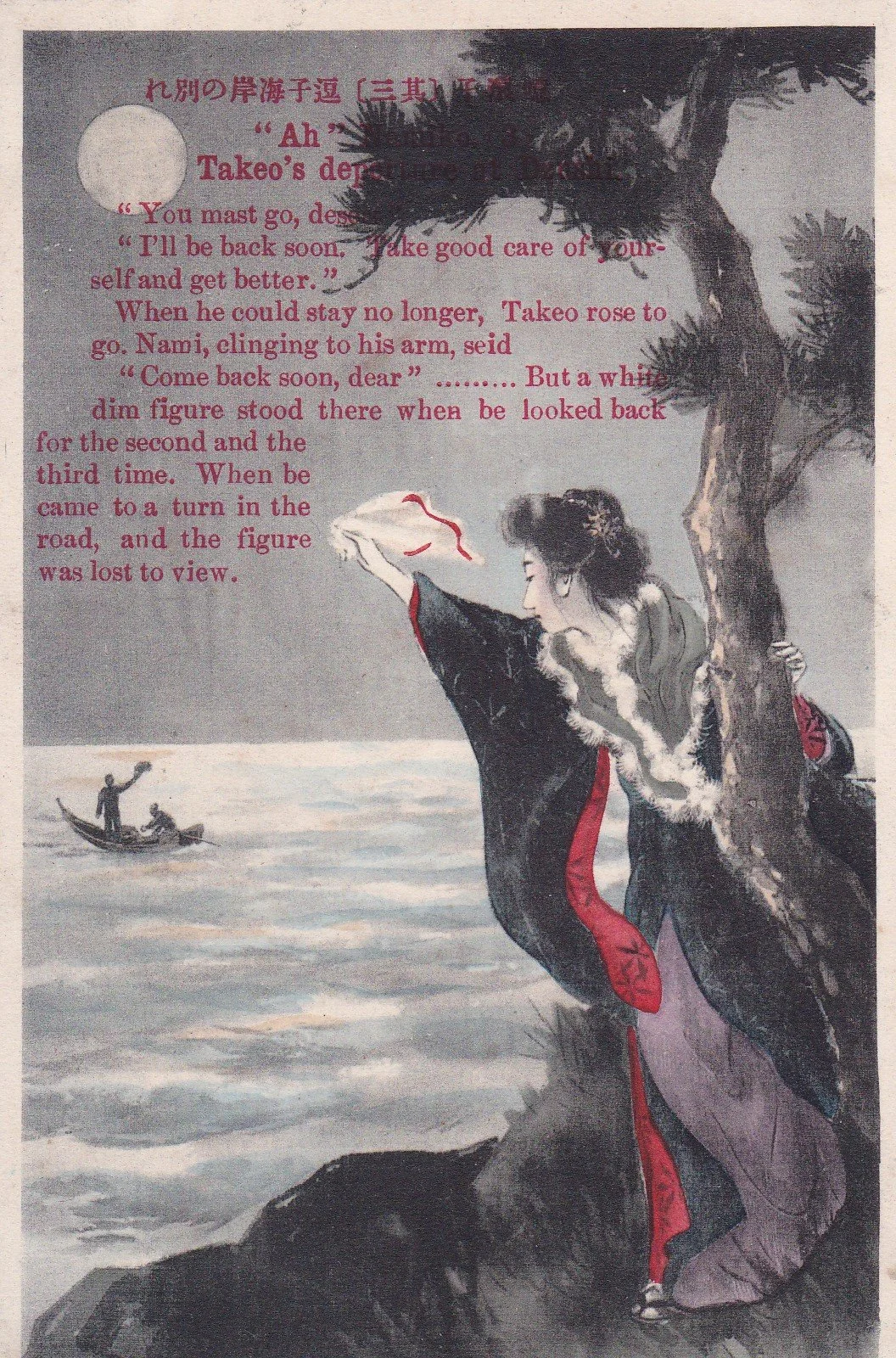

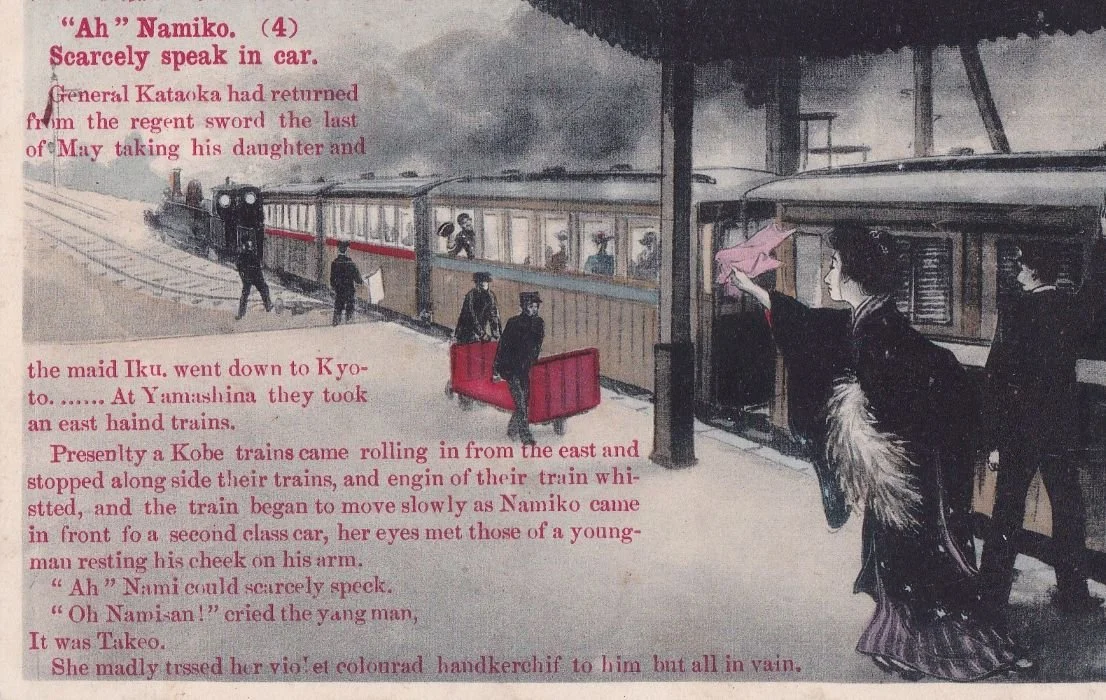

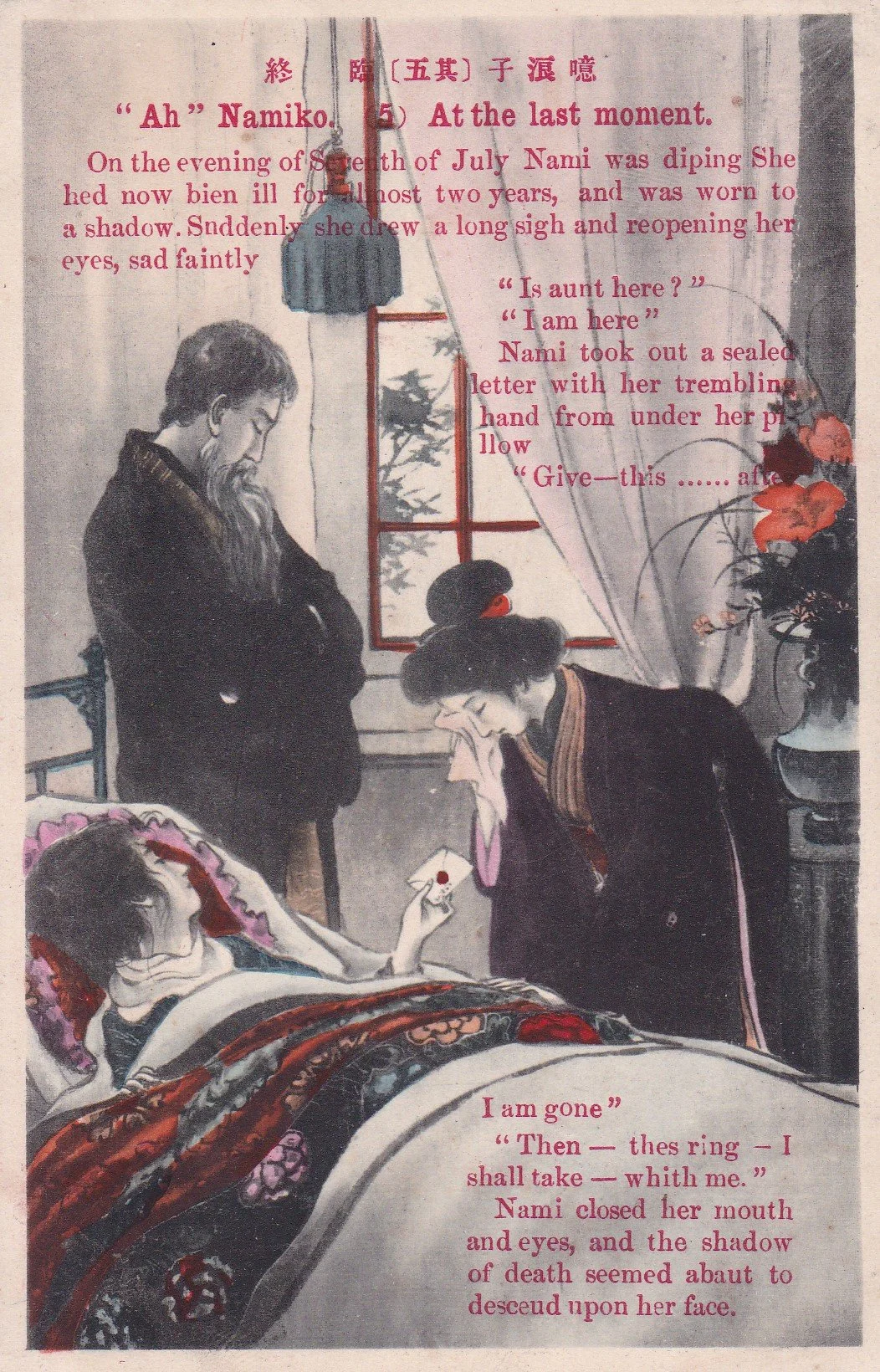

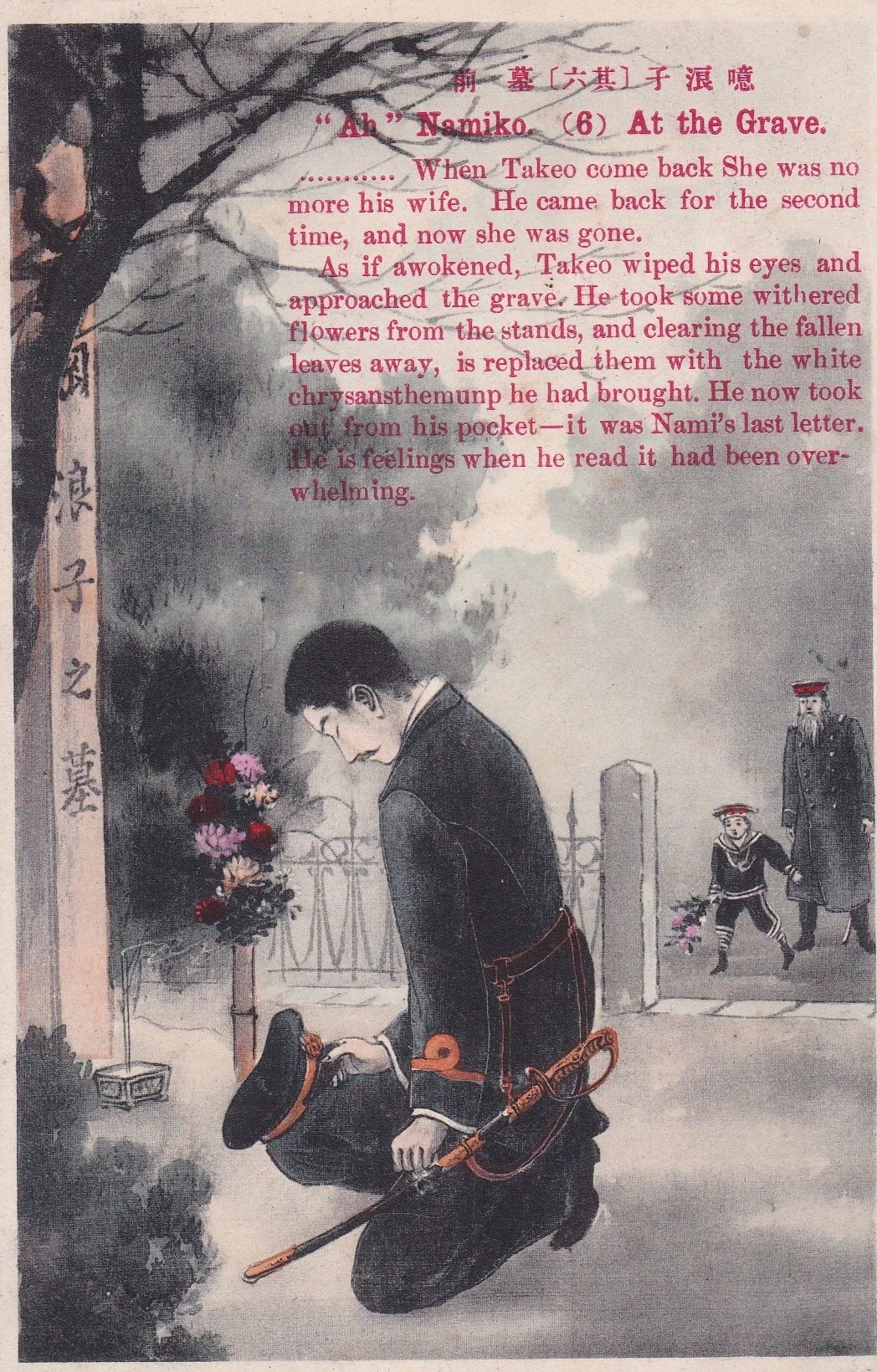

The description above makes plain that this is the same work. What has happened? We have already discussed the attraction to a British audience of seeing a woman best a man in combat using jūjutsu. It could be that this change in billing reflects an attempt to refresh the piece by replacing the vengeance-wreaking son with a vengeance-wreaking daughter. So, who was ‘Miss Namiko’? The name itself is almost certainly taken from the heroine of the popular Japanese novel Hototogisu (不如帰, the Cuckoo), which, under the title ‘Nami-ko’ was published in translation in Europe and America in 1904 and widely read.[56] (A complete aside: after its publication, the story of Nami-ko was a very popular subject for postcard sets in Japan—see gallery at the end of this article).

As to the identity of the performer? It seems to me that there are two main possibilities. The first is that this was still Kawamura, whom, as I stated above, I believe to have been an onnagata, so well able to convince in a fully female role. The second is that it was a Japanese actress adept at jūjutsu who was living in London in 1910. We have already encountered two possible candidates—Omoyo Murakami Long and the unidentified woman who performed jūjutsu demonstrations at the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition. Of course, the latter may have been Omoyo Murakami Long. There are still other candidates among the other Japanese and Anglo-Japanese performers in London that winter, which included some of the performers from the Exhibition who were still to return to Japan.

My best guess? That it was Kawamura. However, even then, as he was playing a female role, this production still deserves its place in this survey, as the audience believed they were seeing a woman overcome a male antagonist using jūjutsu. Arguably, the piece was more powerful with this change to the sex of the protagonist.

In truth, there is still much about the whole Udagawa, Kawamura, Miss Namiko affair that is mysterious, not least the possibility that the Udagawa and Kawamura who performed on stage in England were not the Udagawa and Kawamura who acted in the Pathe Frères film, but imitators. It is telling in this respect that they debuted two weeks after the film premiered, time enough to have worked up an act based on a viewing of the film. A photograph of Udagawa was published in the British press; comparing this with the images of Udagawa as the bandit in the Pathe Frères film, I think I see similarities in the jawline and the eyes, but it is hard to tell for certain, given the makeup that Udagawa wears as the bandit. Similarly, it is possible that Udagawa and Miss Namiko were imitators who took to the stage in November after the ‘real’ Udagawa and Kawamura ended their performances in October. There is even an outside chance that the film was shot in England, not France, as 1910 was the year that the Pathe Frères began shooting fiction films alongside newsreels in England, and, of course, we know that large parts of the White City, Shepard’s Bush, had been turned into a facsimile of Japan, ready to be used as sets.[57]

For my part, I think that all three productions were the work of the same two men, Udagawa and Kawamura, who visited France on the instructions of Otojirō Kawakami, where they shot the film, then travelled to England, where they performed the stage play in two versions, the second with Kawamura making use of his onnagata training, before returning to Japan in late November 1910, at the same time as many of the performers and artisans from the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition.

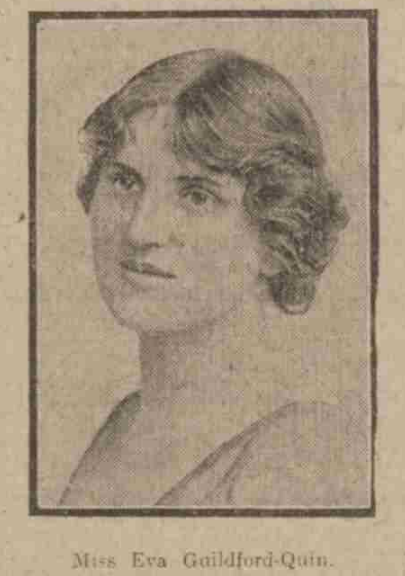

Which brings us, full circle, to the beginning of 1911, and the morality ‘playlet’, ‘What Every Woman Ought to Know’.

But his respect for her, and his promise of reformation, is evidently only due to her prowess at Ju-jitsu. Miss Eva Quin acted with alertness and a quiet sense of the fun of the situation as the woman, and the drunken and cowardly husband was played with much grim humour by Mr. Martyn Roland, the encounters between the couple being very smartly worked. A novel and diverting interlude that won a hearty recall for its clever interpreters.[58]

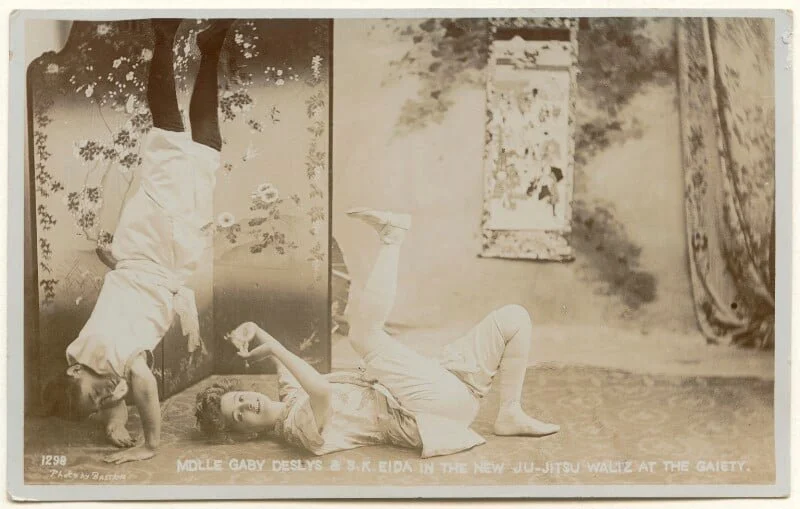

The playlet, written by actor and author Cecil Armstrong,[59] was not only rehearsed at Edith Garrud’s jūjutsu studio on Argyll Street, but also directly inspired by Garrud’s views of women’s self-defence, as expressed in a March 1910 essay in the journal of the Women’s Social and Political Union, Votes for Women.

Whatever the future may have for us, there is no doubt that the average women is weaker, in muscular strength, than the average man. Yet in modern life it is not actual muscle that tells. Agility, alertness, dexterity, and endurance are usually of more importance, as the lessons of the Russo-Japanese war have taught, and it is the Japanese fine art of ju-jitsu or self-defence that has proved more than a match for mere brute force, and that is, therefore, not only a good accomplishment, but a necessary safeguard for the woman who has to defend herself through life.[60]

In her advertising for her studio, Garrud positioned herself as someone who ‘teaches women and children to protect themselves from hooligans and bullies.’[61] Armstrong’s work was that philosophy turned into a morality play.

The two leads were Martyn Roland (1883–?), a jobbing Scottish actor, and Eva May Quin (1885–1956), daughter of New Zealand newspaper proprietor William Chamberlain Quin. Quin, who also performed under the name Eva Guildford Quin, was an active member of the Women’s Social and Political Union as well as an actress, and even accompanied Sylvia Pankhurst on Pankhurst’s second visit to the US in January 1912. She is a strong candidate for being a member of Edith Garrud’s 1913 ‘Bodyguard Unit’. Quin had travelled to Britain in early 1910 on board the White Star Dominion Line ship, the SS Suevic. On board, she met and fell in love with the ship’s doctor, William Graeme Robertson, and the couple married on 1 January 1911, shortly before Quin began rehearsals for ‘What Women Ought To Know’. Quin would continue her acting and activism throughout the marriage, which ended tragically with William Graeme Robertson’s death in 1924, aged just 45. This appears to have marked the moment of Quin’s retirement from the stage, too.[62]

Roland and Quin toured ‘What Every Woman Ought to Know’ around the English halls from April 1911 until May 1912. Alas, I have been unable to find any information on how they rehearsed/trained while on the road, or if they had understudies. As an aside, the pair would perform together again in 1919 in another one-act drama, ‘The Unexpected’.[63]

Although, as he quote above shows, the piece was well received by audiences, it is not clear to what extent it had the desired effect of mobilising women to take up jūjutsu to defend themselves from ‘hooligans and bullies’. It is noticeable that the press treated it purely as a piece of theatrical entertainment, commenting that Quin and Roland could do more to bring out the humour in the piece, which would seem to miss the point by some distance.[64]

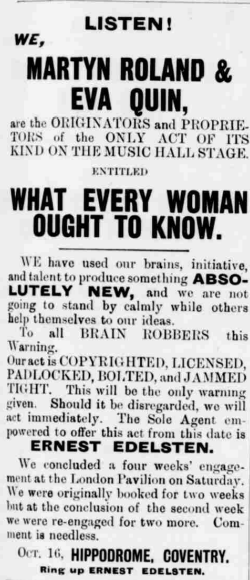

One incident of note during the run was Roland and Quin, who described themselves as the show’s ‘originators and proprietors’, taking out a strongly worded notice in the theatrical press, warning ‘brain robbers’ that the show was copyrighted and they would take action immediately if this was disregarded.[65] Although it’s not possible to determine the target of the pair’s ire at this remove, it is worth noting that both the Falco and Iida act and the Enzer and Miss Clarice act were still active in 1911—did one or both acts replace a ‘hooligan’ with a husband in their demonstrations of women using jūjutsu to defend themselves? Perhaps, but it could be, rather, that Roland and Quin heard that a drama copying their own was in rehearsal and their warning had the desired effect.

WOMEN'S FREEDOM LEAGUE FAIR. The Women’s Freedom League opened yesterday at Caxton Hall a “Green, White and Gold Fair,” which will be continued to-day. The organisers presented a very elaborate and attractive programme, which kept together a large and interested audience for close upon five hours[…]there was an exhibition of nursing by Miss Bigg (matron of the Women's Hospital for Children, Harrow-road), and a jiu-jitsu display by Mrs Garrud, a clever exponent of this Japanese art of wrestling.[66]

Famously, the Women’s Social and Political Union, which had engaged in acts of civil disobedience and even fire-bombings in the cause of women’s suffrage before 1914, not only suspended direct action at the outbreak of World War One but became actively involved in supporting the war, while its pacifist offshoot, the Women’s Freedom League, continued to campaign both for women’s suffrage and against the war. Edith Garrud actively supported the Women’s Freedom League and would continue teaching jūjutsu alongside her husband, William, until 1925.[67]

The return of peace in 1918 saw the enfranchisement of women over the age of 30, which, although far from representing universal suffrage, was enough to rob the suffragist campaign of most of its support. The sociopolitical debate in Britain, haunted by the scale of suffering that the war had inflicted, moved on. Nineteen Eighteen brought changes to the jūjutsu community of Great Britain, too, as this was the year that Japanese businessman Gunji Koizumi (小泉軍治, Koizumi Gunji; 1885-1965) founded the Budokwai (武道会, Budōkai; Society of the Martial Way), the martial arts club that would introduce not just Britain but also Europe to jūdo. Back in the early 1900s, Koizumi had taught jūjutsu alongside Sadakazu Uyenishi, Edith and William Garrud’s teacher.[68] His new club was open to both Japanese and European members, male and female. One of the first female members to join was Sarah Mayer (1896–1957), who would go on to become the first non-Japanese woman to gain a black belt in jūdo.[69] During her life, Mayer was better known by her stage name, Sarah Tapping. She was an actress: the connection between jūjutsu and the world of the stage in Britain, forged in its earliest days, continued.

Jamie Barras, November 2025, revised December 2025.

Back to The Spectacle

Notes

[1] ‘What Every Woman Should Know’, Daily Mirror, 29 March 1911.

[2] Mike Callan, Conor Heffernan, and Amanda Spenn, “Women’s Jūjutsu and Judo in the Early Twentieth-Century: The Cases of Phoebe Roberts, Edith Garrud, and Sarah Mayer.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, 2018, 35 (6), 530–53. doi:10.1080/09523367.2018.1544553. Battle of Glasgow: Hannah Brown, ‘The Battle of Glasgow: Scotland's 'hidden' history of suffragettes and self-defence from 'Suffrajitsu' to Indian clubs’, https://www.scotsman.com/heritage-and-retro/heritage/scotlands-hidden-history-of-suffragettes-and-self-defence-3302979, accessed 5 November 2025. For what might be a glimpse of Edith Garrud in action, see 0.45–1.18 of this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W5Z5LcwgxRM, accessed 5 November 2025.

[3] For a comprehensive look at the early history of jujutsu in Britain, including the contributions of Edith Garrud, Sadakazu Uyenishi, Yukio Tani, and Taro Miyake, see: Roy Case, ‘Bartitsu: The Art of Self-Defence’, Parts I and II, Playing Pasts, https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/general/bartitsuthe-art-of-self-defencepart-1/, https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/general/bartitsuthe-art-of-self-defencepart-2/. The story of ‘Bartitsu’—the ‘baritsu’ of the Sherlock Holmes story ‘The Adventure of the Empty House’—is also covered in depth in articles published by the Bartitsu Society: https://bartitsusociety.com/, accessed 5 November 2025. I will often refer to articles on this site in this piece.

[4] Amy Dawes, “THE FEMALE OF THE SPECIES: Magiciennes of the Victorian and Edwardian Eras.” Early Popular Visual Culture, 2007, 5 (2), 127–50. doi:10.1080/17460650701433780. https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-rifle-nell, accessed 5 November 2025. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp64790/vesta-tilley-matilda-alice-nee-powles-lady-de-frece, accessed 5 November 2025.

[5] ‘Dramatic Gossip’, The Referee, 24 February 1907.

[6] http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/GaietyTheatreLondon.htm, accessed 5 November 2025.

[7] https://gsarchive.net/british/newaladdin/index.html, http://www.lily-elsie.com/shows.htm#new, accessed 5 November 2025.

[8] Sur La Plage lyrics: https://gsarchive.net/british/newaladdin/lyrics/tna20.html, accessed 5 November 2025. ‘Rather daring bathing costume’: ‘Gaiety Theatre: The New Aladdin’, Westminster Gazette, 1 October 1906.

[9] Gaby Deslys: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp52143/gaby-deslys-marie-elise-gabrielle-caire, https://intothelimelight.org/2016/02/01/509/, accessed 5 November 2025.

[10] Rahn, Ono, and jujutsu in Berlin: Wojciech Cynarski, Idokan judo in relation to Kodokan judo (1947–2017): remarks on the institutionalisation of martial arts. Sport i Turystyka. Środkowoeuropejskie Czasopismo Naukowe, 2021, 4, 81-96. 10.16926/sit.2021.04.27. ; https://sites.google.com/site/judofamiliar/-vii-judocas-ilustres/miembros-kodokan/akitano-ono-1876---1942; https://www.e-budo.com/archive/index.php/t-21979.html, accessed 10 November 2025.

[11] ‘Deyo’ in London in 1897, which short bio: ‘The Beautiful Deyo’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 21 July 1897. Full name: ‘Walter Jones Marries Again’, The New York Times, 8 April 1908. Blanche Deyo on Broadway in 1906: https://www.ibdb.com/broadway-cast-staff/blanche-deyo-38000, accessed 10 November 2025.

[12] Suyekichi Iida: https://bartitsusociety.com/the-japanese-school-of-ju-jitsu-in-oxford-street-1904-08/, https://footlightnotes.wordpress.com/2013/08/31/a-real-photograph-postcard-of-mdlle-gaby-deslys/, https://fujimizaka.wordpress.com/2019/12/24/luxun-67/, accessed 5 November 2025. Phoebe Roberts: Note 2 above, first reference.

[13] James Jupp, ‘My Thirty Years at the Gaiety: Gaby Deslys as I Knew Her’, Sunday Post, 29 October 1922.

[14] Harry Gratton ‘arranged all the dances’ for ‘The New Aladdin’: ‘Chose & Autres Choses’, Sporting Life, 6 October 1906.

[15] ‘Birmingham Amusements: The Hippodrome’, Birmingham Mail, 4 September 1906.

[16] https://selftaughtjapanese.com/2014/03/21/japanese-honorific-prefixes-%E3%81%8A-and-%E3%81%94-o-and-go/, accessed 5 November 2025.

[17] https://ninjin.co.uk/murakami-kumakichi/, accessed 5 November 2025.

[18] A surviving period short-sleeved uwagi: https://bartitsusociety.com/antique-english-jujutsu-gi-discovered/, accessed 6 November 2025.

[19] https://civiliancombatives.wordpress.com/2015/04/02/demonstrating-jiu-jitsu-in-the-edwardian-period-was-it-all-just-a-show/, accessed 6 November 2025.

[20] Edwardian women’s gi: https://bartitsusociety.com/london-athletic-academy-where-ladies-learn-jujitsu-1908/, accessed 6 November 2025.

[21] ‘The World of Women: The Charm of Paris’, Penny Illustrated Paper, 29 December 1906.

[22] Chiung Hwang Chen, Feminization of Asian (American) Men in the U.S. Mass Media: An Analysis of The Ballad of Little Jo, Journal of Communication Inquiry, 1996, 20(2), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/019685999602000204 (Original work published 1996).

[23] ‘New Cross Empire’, Sydenham, Forest Hill & Penge Gazette, 21 September 1907.

[24] See Note 10 above. Last mention of Falco and Eida act in UK: ‘Amusements: Royal Hippodrome’, Belfast News-Letter, 25 December 1913.

[25] Biographical information on Frank Long: search Francis William Long, Births, Marriages, and Deaths: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl, accessed 6 November 2025.

[26] ‘Norwich: Hippodrome’, Eastern Evening News, 10 December 1906.

[27] Frank Long from Islington: entry for Frank Long and daughter Patricia Long, 1911 and 1921 England Censuses, Islington district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 5 November 2025. Frank Long (‘Professor Long’) at St Gabriel’s: ‘St Gabriel’s Amateur Gymnastic Club’, Hampstead & Highgate Express, 19 April 1902. Naval Reserve: ‘Gymnastic Club Entertainment at Cricklewood’, Hendon & Finchley Times, 7 April 1905. Japanese jujutsu practitioners: ‘St Gabriel’s Gymnastic Club’, Hendon & Finchley Times, 6 April 1906. Student of ‘Apollo’ (Bankier) and tutor of Royal Irish Constabulary and Royal Navy: ‘Ipswich Hippodrome: the Ju-Jitsu Wrestlers’, Evening Star, 18 December 1906.

[28] ‘Local Amusements: The Palace’, Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette, 2 July 1907. The text actually reads ‘Oyama’, not ‘Omoyo’, but this was a common typo of the period. For an instance of the correct spelling in 1907, see, for example, ‘Stoke-on-Trent: The Hippodrome’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 27 September 1907.

[29] ‘Ju-Jitsu Championship. Sporting Life, 3 March 1908; ‘The Ju-Jitsu Championship. Sporting Life, 4 March 1908. Paul Bradley Mihalop: ‘Tournament Events’, Hampshire Telegraph, 27 March 1909; https://www.naval-history.net/WW1NavyBritishLG-Royal_Navy_Medals-Index2.htm, accessed 6 November 2025. Years of birth and death: age and year of death, Paul B. Mihalop, Births, Marriages, and Deaths: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl, accessed 6 November 2025.

[30] Omoyo still on stage, March 1908: ‘Cardiff: Palace and Hippodrome’, Era, 14 March 1908. Return of Omoyo: ‘Music Halls & Theatres: South London Palace’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 15 May 1908.

[31] ‘Wrestling Challenges, &c.’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 30 May 1908.

[32] Roberts Challenge: ‘Wrestling Challenges, &c.’, Boxing World and Mirror of Life, 30 May 1908. Roberts and Hirano on stage: ‘Palace Theatre Tournament’, Manchester Courier, 25 June 1908. Bankier and Roberts: ‘London Athletic Academy Where Ladies Learn Ju-Jitsu’, Daily Mirror, 24 November 1908.

[33] ‘Bristol: The Palace’, Era, 12 December 1908.

[34] Enzer biography: ‘Smart Soldier Gymnast’, Football Post (Nottingham), 26 December 1908. Enzer jujutsu act: ‘Preston: Royal Hippodrome’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 20 September 1907. ‘Soldier Juggler’, ‘lady ju-jitsu expert’: ‘Amusements, &c: Empire Palace’, Portsmouth Evening News, 4 September 1909. Years of birth and death for John and Johanna Enzer: Births, Marriages, and Deaths: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl, accessed 6 November 2025. Clarice Enzer: entry for John Enzer and Johanna Enzer, 1901 England Census, Sheffield district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 7 November 2025. Johanna Enzer 1911: entry for Johanna Enzer, Eileen Enzer, Maud Enzer, Scarborough district, 1911 England Census; John Enzer 1911: entry for John Enzer, Clarice Maud Enzer, Jack Enzer, Southport district, 1911 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), 11 November 2025.

[35] ‘Entertainments: His Majesty’s Theatre’, Dominion (Wellington, NZ), 17 July 1915.

[36] https://ejmas.com/jmanly/articles/2003/jmanlyart_wolf_0903.htm, accessed 7 November 2025.

[37] John Enzer still performing same routine in 1922: ‘Pentre: Workmen’s Hall’, Era, 19 July 1922. See also entry for John Enzer and Clarice Maud Enzer, 1921 England Census, Ecclesall district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 11 November 2025.

[38] ‘Derby: Palace of Varieties’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 27 November 1908.

[39] Kennedy Kiddies debut and ‘ju-jitsu dance’ ‘invented’ by Kennedy: ‘Public Amusements: Argyll Theatre’, Birkenhead News, 22 July 1908. Dozen ‘maidens’: ‘The Theatres: Palace, Attercliffe’, Sheffield Independent, 20 October 1908. ‘Youngsters: ‘Amusements in Derby: Palace’, Derby Daily Telegraph, 24 November 1908. Name change: ‘Liverpool: Grand Tivoli’, Era, 22 May 1909. ‘Arthur Kennedy M.A.’: ‘Southend-on-Sea: The Kursaal’, Era, 31 July 1909.

[40] See Note 34 above, final reference, and ‘The Camden Hippodrome’, Finsbury Weekly News and Chronicle, 17 June 1910. Wrestling Miss Carroll: ‘The Kursaal’, Southend Standard and Essex Weekly Advertiser, 2 September 1909.

[41] Last mention of Kennedy jūjutsu dance: ‘Camden Hippodrome’, Era, 1 October 1910. Troupe re-emerges, still a juvenile troupe: ‘Tottenham Palace’, Era, 23 March 1912.

[42] Steven Kent, ‘When Japan Occupied London: Remembering the Japan Britain Exhibition of 1910’, https://www.epoch-magazine.com/post/when-japan-occupied-london-remembering-the-japan-britain-exhibition-of-1910; https://www.benjidog.co.uk/WhiteCity/1910.php, accessed 11 December 2025.

[43] ‘Fighting Men and Wrestlers of Japan at the White City, Shepard’s Bush’, The Sphere, 4 June 1910.

[44] Pernille Rudlin had researched the performers in this group extensively: https://ninjin.co.uk/1910s/, accessed 11 December 2025.

[45] https://bartitsusociety.com/martial-arts-displays-at-the-japan-british-exhibition-of-1910/; female jujutsu practitioner: https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2017/07/20/on-the-border-5-the-japan-british-exhibition-1910/, accessed 11 December 2025.

[46] ‘Fighting Men and Wrestlers of Japan at the White City, Shepard’s Bush’, The Sphere, 4 June 1910.

[47] https://www.fondation-jeromeseydoux-pathe.com/document/chatiment-du-samourai-le-1910/620fc678f01ae02d35a5d2b7?q=chatiment%20du%20samourai&pos=1, accessed 11 December 2025.

[48] ‘Vengeance as an Art’, London Daily Chronicle, 16 August 1910.

[49i] Teigeki: ‘Tokyo and Yokohama’, London and China Telegraph, 24 October 1910; Udagawa and Kawamoura from ‘Imperial Theatre, Tokio’: ‘A Real Japanese Play...’, Bulletin (Sydney, NSW), 25 August 1910.

[49ii] Kawakami and the Imperial Theatre (in Japanese): https://www.ndl.go.jp/en/landmarks/column/teikoku_gekijo, accessed 25 January 2026. Udagawa and Kawamura in 1908 Kawakami Troupe on France tour: Recueil factice d'articles de presse et programmes, concernant l'actrice Sada Yacco et les pièces où elle a joué, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb38691845s, accessed 25 January 2026. More on Sada Yacco: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-fireflies, accessed 25 January 2026.

[50] See Note 48 above.

[51] It is worth saying here that the Atsuta Maru, the ship that brought the majority of the Japanese performers and artisans of the Exhibition to Britain, did include three men named Kawamura in its list of passengers. However, a) all three men were listed as ‘artisans’, not ‘performers’; and b) the only ‘Utagawa’ on board was Wakana Utagawa (歌川若菜, Utagawa Wakana), a young female artist who would gain some fame in Europe and the US across the following few years: passenger lists for the Atsuta Maru, arrived London 28 April 1910, UK, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 10 December 2025. Wakana Utagawa (in Japanese): http://artistian.net/wakana_utagawa/, accessed 11 December 2025.

[52] ‘The Coliseum’, Morning Post, 16 August 1910.

[53] ‘The Coliseum’, Morning Post, 16 August 1910.

[54] Final Udagawa & Kawamura-billed performance: ‘Empire Theatre, Hurst Street’, Birmingham Mail, 22 October 1910.

[55] ‘The Coliseum’, Morning Post, 16 August 1910.

[56] https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/125/, accessed 11 December 2025.

[57] Photograph of Utagawa: ‘Japanese Drama’, Football Post (Nottingham), 1 October 1910. Pathe in England: https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/newsonscreen/search/index.php/person/1349, accessed 11 December 2025.

[58] ‘The Metropolitan’, Era, 11 June 1911.

[59] See Note 1 above.

[60] Edith Garrud ‘The World We Live In’, Votes for Women, 4 March 1910.

[61] ‘London Amusements: Ju-Jutsu’, Daily Mirror, 11 March 1911.

[62] Information on Martyn Roland, which appears to have been a stage name, comes from his entry in the 1911 England Census: entry for Martyn Roland, St Giles district, 1911 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 7 November 2025. The return also includes an entry for Roland’s wife, Mary, and the information that the couple had been married for three years and had two children living. Information on Eva Quin is assembled from a number of sources, including her own entry in the 1911 England Census, Ealing District, which includes her place of birth (Dunedin, New Zealand), which helps connect this Eva Quin to Eva May Quin, daughter of William Chamberlain Quin. To this can be added: entry for Eva Quin, passenger lists for the SS Suevic, arrived London 17 April 1910, UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960; marriage registration for Eva May Guildford Quin and William Graeme Robertson, 1 January 1911, Liverpool, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1935; entries for Eva Graeme Robertson and Estella [Sylvia] Pankhurst, passengers lists for RMS Oceanic, arrived New York, 11 January 1912, New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957; search for Eva Graeme Robertson, Births, Marriages, and Deaths, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl, accessed 6 November 2025. Death of William Graeme Robertson: ‘Death: Robertson’, Journal of Commerce (Liverpool), 13 June 1924.

[63] Final performances of What Every Woman Ought to Know: ‘Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Pavilion’, Era, 25 May 1912. Roland and Quin in ‘The Unexpected’, 1919: ‘First Nights of the Week: The Unexpected’, Era, 25 June 1919.

[64] ‘London Variety Stage: The London Pavilion’, Stage, 14 September 1911

[65] ‘Listen!’, Era, 14 October 1911.

[66] ‘Women’s Freedom League Fair’, London Daily Chronicle, 27 November 1915.

[67] See Note 2 above, first reference.

[68] https://budokwai.co.uk/history, accessed 7 November 2025.

[69] See Note 2, first reference.

Gaby Deslys and Suyekichi Iida, The Jujutsu Waltz, 1907. Photograph by Bassano Ltd. National Portrait Gallery. Creative Commons Licence. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw206402/

Advert for Edith Garrud's jujutsu classes, 1911. Campaign for Universal Women's Franchise Rights, 1 October 1911. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

The New Aladdin, Gaiety Theatre, 1906. Morning Post, 12 October 1906. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Gaby Deslys and Suyekichi Iida (S.K. Eida), Ju-jitsu Waltz, People's Illustrated Paper, 4 April 1907. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Dejo Sisters, Empire News, 17 March 1907. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Kennedy Girls Ju Jitsu Dance, Southend Standard, 15 July 1909. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Eva May Quin, Dundee People's Journal, 18 April 1914. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Listen! Era, 14 October 1911. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Still from Le Châtiment du Samouraï (1910), starring Udagawa (left) playing the father and Kawamura (right) playing the son. Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé. Link in the endnotes.

Still from Le Châtiment du Samouraï (1910), starring Udagawa (left), now playing the bandit, and Kawamura (right), playing the son now dressed as a woman. Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé. Link in the endnotes.

Jujutsu in the film's climactic fight. Still from Le Châtiment du Samouraï (1910), starring Udagawa (left) and Kawamura (right). Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé. Link in the endnotes.

The Nami-ko (Hototogisu (不如帰, the Cuckoo) story in postcard form, 1/6. Author's own collection.

The Nami-ko (Hototogisu (不如帰, the Cuckoo) story in postcard form, 2/6. Author's own collection.

The Nami-ko (Hototogisu (不如帰, the Cuckoo) story in postcard form, 3/6. Author's own collection.

The Nami-ko (Hototogisu (不如帰, the Cuckoo) story in postcard form, 4/6. Author's own collection.

The Nami-ko (Hototogisu (不如帰, the Cuckoo) story in postcard form, 5/6. Author's own collection.

The Nami-ko (Hototogisu (不如帰, the Cuckoo) story in postcard form, 6/6. Author's own collection.