A House of Refuge

Jamie Barras

Trigger warning for quotes from period sources containing terms we recognise today as slurs

"The Whole Hog or None." TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—In your admirably written Music Hall History there is a small mistake. You quote Mr Ware as the author of the song "The Whole Hog or None." Now, I brought the song in question from America, and sang it at Wilton's Music Hall more than thirty years ago. I got the song from Tim Norton, brother of the well-known Wash Norton, both of whom were members of the then famous Bryants Minstrels. There are living witnesses to the truth of my statements—viz., Mr John D'Auban and sister, who were then engaged at the same hall, and Mr Sam Tute, musical director. Yours truly, ORVILLE PITCHER (formerly known as Orville Parker). 19, Harrington-grove, Finsbury-park, N.[1]

For some performers, blackface was more than simply makeup; it was a mask for them to hide behind. Such was the case with Orville Oscar Pitcher (1834/5–?), a white performer of blackface minstrelsy who had a 50-year career in the English halls. For the early part of that career, he performed under the name Orville Parker. More than simply a stage name, Parker was an identity that Pitcher adopted to escape the sins of his past.

STATE NEWS. Dr Almon Pitcher, of Gouverneur, formerly for several years a practising physician in Boonville, died November 23, aged around 84.[2]

Orville Oscar Pitcher was born in upstate New York in 1834 or 1835, the second son of farmer and physician Almon Pitcher (1798-1882) and his wife Julia Pitcher née Holmes (1806-1876). Almon (sometimes written ‘Almond’) Pitcher belonged to the fourth generation of the Pitcher family to have been born in North America, his great-great-great-grandfather, Andrew Pitcher, having settled in the Massachusetts colony no later than 1634. Almon’s father had fought in the Revolutionary War, and his brother Reuben had fought in the War of 1812; another of his brothers was a Baptist preacher, and Almon was himself a physician. The Pitchers were, in short, a family of some standing in early Nineteenth-Century upstate New York.[3]

(I think it would be beneficial if I break the timeline for a moment to present the three pieces of evidence that connect Almon Pitcher and Orville Pitcher, noting that Orville Pitcher is not named in any census return for the Almon Pitcher family—for reasons we will see below: 1) In his 1865 marriage to Charlotte Sutton, in Liverpool, England, Orville Oscar Pitcher, ‘musician’ names ‘Almond Pitcher, surgeon’ as his father; 2) In his will registered after his death in 1882, Almon Pitcher names ‘Orville O. Pitcher, of London, England’ as a beneficiary; 3) In his entry in the passenger lists for the SS Caledonia arriving in New York in May 1911, Oscar Pitcher, ‘actor’, lists ‘Gouverneur’ as his destination—Gouverneur, as we will see, was the location of the Almon Pitcher family farm (although Almon himself was by this time long dead).[4])

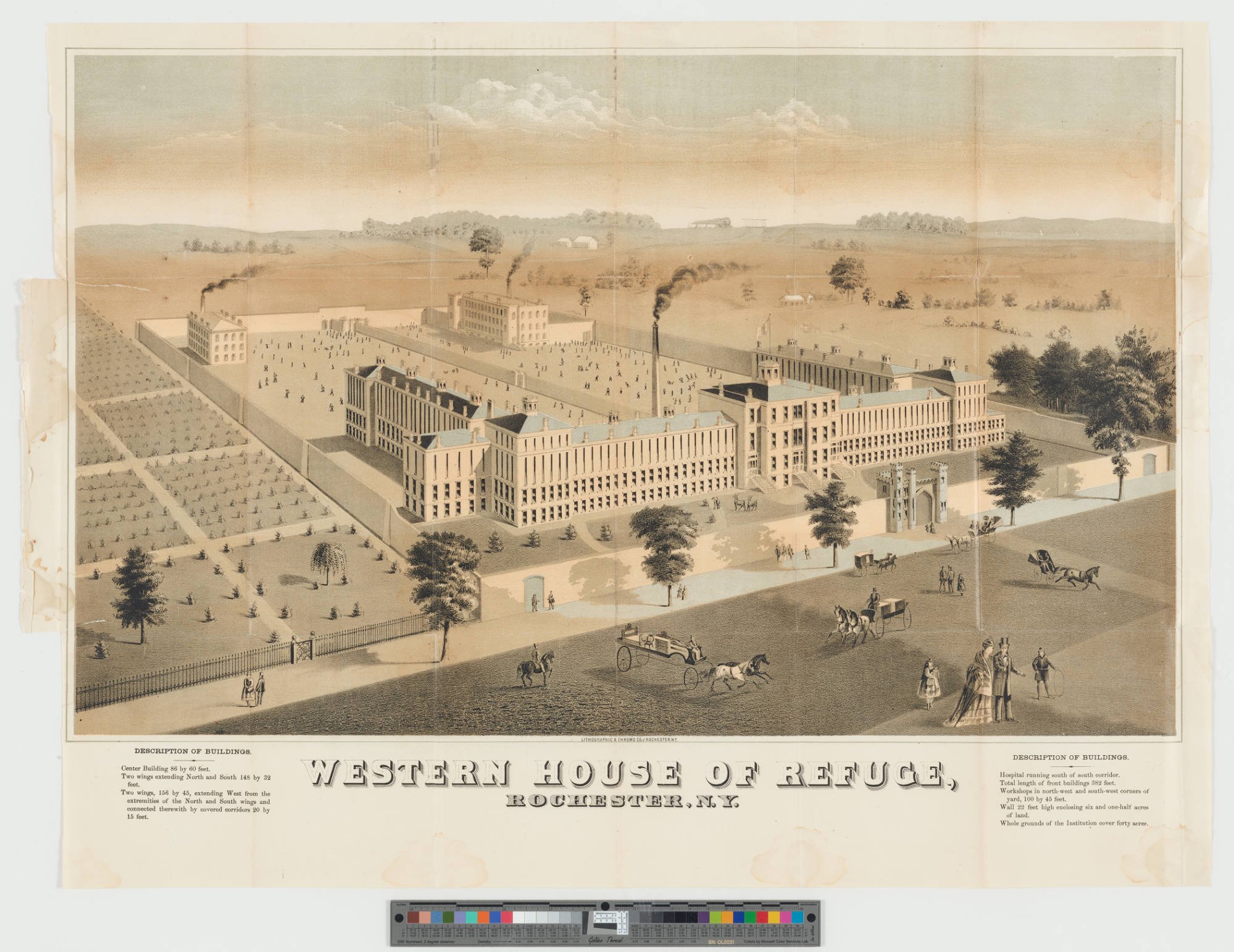

The 1840 US Federal Census found the Pitcher family, Almon and Julia, and their four children, unnamed in this Census return, living in Oneida County, New York, farming land near the town of Boonville; Almon was also, by this time, practising as a physician. A year later, Julia gave birth to a fifth child, a daughter, Livilla. By the late 1840s, the Pitchers had bought a property valued at $1700—a very considerable landholding—in St Lawrence County, near Gouverneur, then part of the small town of Oswegatchie. Sometime between 1840 and 1850, they lost one of their children. Within a few short years of the move to St Lawrence, they would experience two further tragedies: in 1854, their youngest child, Livilla died, aged just 13; but, before this, in late 1849 or early 1850, Orville Pitcher, the younger of their two sons, then aged 16, was convicted of the crime of burglary and incarcerated in the Western House of Refuge, Rochester, New York.[5]

About one and a half miles from the center of [Rochester], on an eminence commanding a fine view of the city, surrounding country and Lake Ontario, with the Genesee River on the east and the Erie Canal on the west, stands the ‘Western House of Refuge for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents’.[6]

The Western House of Refuge of Rochester, NY, was so-named as it was built to serve the needs of the communities of western New York State, not met, it was felt, by the New York House of Refuge in Manhattan. The latter, already nearly a quarter century old by the time the Rochester institution was opened in August 1849, was the USA’s first juvenile reformatory, built out of a recognised social need to separate children imprisoned for crimes from the malign influence of adult inmates.[7]

Orville Pitcher’s name appears on the 1 June 1850 US Federal Census return for the Western House of Refuge, which shows that at the time the institution housed 66 inmates, all boys. Although 12 was the age of criminal responsibility, New York had outlawed the imprisonment of children 16 and younger just a few years earlier (1846), so it seems likely that Orville was either newly convicted or had been incarcerated in the New York House of Refuge at the time of his conviction and later transferred. It is worth noting here that, as we would expect, Orville Pitcher is noticeable by his absence from the 1850 census return of Almon Pitcher and family, despite his two older siblings, Albert and Ann, and younger sibling, Livilla, still being at home.[8]

Orville’s crime, burglary, was, as shown below, the second most frequent offence committed by the children sent to the Western House of Refuge in its first year of existence.

Arson Burglary Disorder Forgery Grand Larceny Petty Larceny Robbery Vagrancy

Inmates 2 15 2 1 10 28 1 3

To modern eyes, the most striking thing is the ages of the inmates. Although the average age was 15, this masks the fact that the youngest was only 8 years old (John Fogerty, born in Ireland, incarcerated for petty larceny). And then there was the case of Isaac Stivans, incarcerated, aged 9, for the crime of arson—although the reformatory system was a step up from imprisoning children alongside adults, it was still a long way from addressing the specific welfare needs of children accused of serious crimes.

For our purposes, the most intriguing inmate, in addition to Orville Pitcher himself, was Charles Johnson, an 18-year-old African American youth—the only inmate described as ‘black’ in the census, alongside four inmates described, in the language of the day, as ‘mulatto’. Johnson’s crime was petty larceny, the most common offence committed by children sent to the House of Refuge in its first year of existence. However, of most interest to us is the ‘profession, occupation, or trade’ recorded in the return for Johnson, that of ‘minstrel’.

GAVIT’S ORIGINAL ETHIOPIAN SERENADERS. Partly from a love of music, and partly from curiosity to see persons of color exaggerating the peculiarities of their race, we were induced last evening to hear these Serenaders. The Company is said to be composed entirely of colored people, and it may be so. We observed, however, that they too had recourse to the burnt cork and lamp black, the better to express their characters and to produce uniformity of complexion.[9]

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) called Rochester, New York, the location of the Western House of Refuge, home for 25 years, and would be laid to rest there after his death in Washington, DC, in February 1895.[10] In June of 1849, two months before the Western House of Refuge opened its doors for the first time, Douglass attended a performance by a troupe of Black performers of blackface minstrelsy called Gavit’s Original Ethiopian Serenaders. The Serenaders were an eight-strong troupe of performers under the directorship of D.E. Gavit, a [white] New York music publisher and photographer. Although billed, in the language of the time, as ‘the original darkies from the South’, given that Gavit was a New Yorker, and the Serenaders performed only a few times and all those performances were in New York State in May and June of 1849, it seems possible, if not likely, that the Serenaders were in fact African American residents of New York.[11]

We know the names of only three of the Serenaders, ‘B. Richardson’, ‘G. Davis’, and ‘Mr Cooper’, and there is nothing that I know of to indicate that there was a member of the troupe by the name of Charles Johnson. However, Black performers of blackface minstrelsy were rare in the years before the American Civil War, particularly in upstate New York, and it seems too much of a coincidence that a Black ‘minstrel’ should be found incarcerated in a reformatory in Rochester, New York, a year after the Serenaders played the city. At the very least, it seems likely that Johnson was, if not a Serenader, a member of a troupe formed in imitation of the Serenaders who performed at some of the same venues in the months immediately following.

Douglass came away from the Serenaders’ performance conflicted about what he had seen but hopeful that it might lead to better things.

We are not sure that our readers will approve of our mention of those persons, so strong must be their dislike of everything that seems to feed the flame of American prejudice against colored people; and in this they may be right, but we think otherwise. It is something gained when the colored man in any form can appear before a white audience; and we think that even this company, with industry, application, and a proper cultivation of their taste, may yet be instrumental in removing the prejudice against our race. But they must cease to exaggerate the exaggerations of our enemies; and represent the colored man rather as he is, than as Ethiopian Minstrels usually represent him to be.[12]

Alas, history was to show that it would be over 100 years before Black performers fully escaped the shadow of the ill-educated ne’er-do-well stereotype that blackface minstrelsy perpetuated—which is how long it took white audiences to see the stereotype as just that. Of course, this was due in no small measure to the popularity of white performers of blackface minstrelsy well into the middle of the Twentieth Century. Frederick Douglass’s own views on the latter, formed as early as 1848, were strong.

We believe he does not object to the "Virginia Minstrels," "Christy's Minstrels," the "Ethiopian Serenaders," or any of the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow-citizens.[13]

I have been unable to determine when precisely Orville Pitcher took his own first steps to becoming a white performer of blackface minstrelsy; nor can I say with any certainty that Pitcher’s encounter with Charles Johnson, a Black performer of blackface minstrelsy, in the Western House of Refuge in 1850, in any way influenced his decision to take to the stage in blackface himself. Pitcher was already a fully fledged performer when he arrived in Britain in 1860, but this does not mean that he began his journey a decade earlier; even if he did, there were performances by white performers of blackface minstrelsy like the Christy Minstrels, Virginia Minstrels, and the original Ethiopian Serenaders, mentioned by Douglass, that he could have seen.[14] However, it is impossible to ignore that someone who followed the career that Pitcher would later take up was locked up with him in the Western House of Refuge.

We can at least be certain that, as early as 1849, Pitcher had already decided that the life of the farmer was not for him: we can view his crime as an attempted escape from that life (he certainly did not do it because of poverty, remembering that his father owned a farm valued at $1700). It is worth noting in this context that in the 1850 census return, Pitcher’s occupation was given as ‘farmer’ and there was only one other boy amongst the inmates of the House of Refuge with the same occupation, George Chase, who was also 16 years old and also convicted of burglary—Pitcher’s partner in crime?

We can also guess at the effect that Orville Pitcher’s conviction had on the rest of his family. For Almon Pitcher, landowner, patriot, physician, and pillar of the Gouverneur community, to have the younger of his two sons arrested, charged, tried, convicted, and incarcerated for a crime, any crime, must have been devastating—and this does not exclude Almon and Julia Pitcher at the same time feeling compassion for their son in his plight. The crime, almost certainly committed against the property of someone known to the Pitchers, if not a family friend, would have been known to everyone in the community. Did the Pitchers’ neighbours blame them for the actions of their son, as was often the case with the parents of children convicted of crimes? Did Almon lose his standing in the community and his authority as a physician? These are questions we cannot answer, but we can surmise that the effect was, at the very least, deeply shaming.

Alas, that shame would only deepen. Orville Pitcher was released from the Western House of Refuge in late 1851 or the first month of 1852. He did not return home, however—if he still had a home to go back to—instead, in February 1852, he enlisted in the US Army. As he lied about his age, claiming to be 21 when he was just turned 18, it seems probable that this was his decision. Regardless, within a few short months, he had decided that Army life, like life on the farm, was not for him: in June 1852, just four months after he enlisted, he deserted. Aged 18, and already an ex-convict, he was now also an army deserter and fugitive. He was, in short, a man in need of a new name and face.[15]

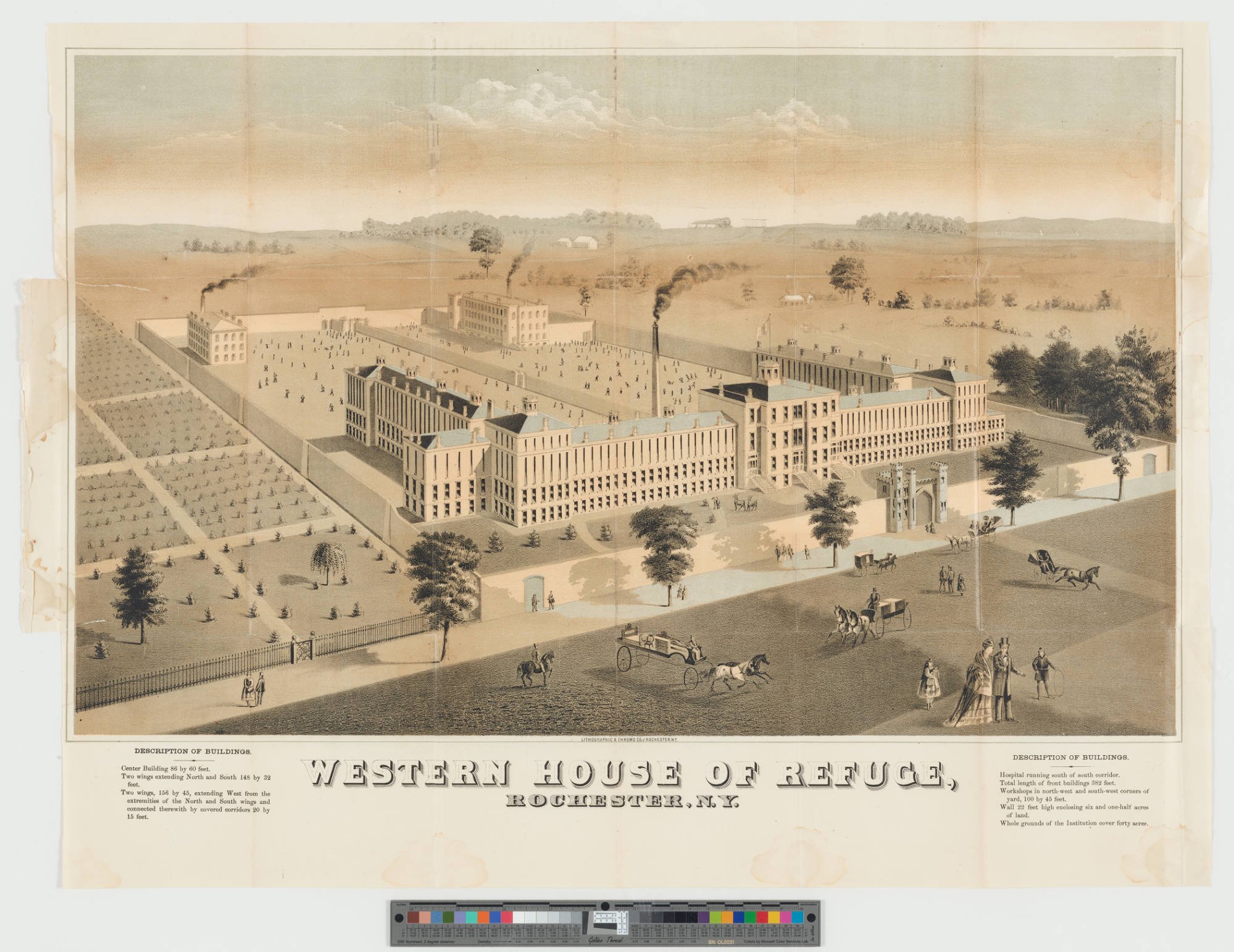

Wilton's Magnificent New Music Hall and Supper Room. Wellclose-square, Leman-street, Whitechapel. The Handsomest Room in London. Proprietor J. WILTON. Open Every Evening. The Proprietor is happy in announcing that, his company comprises the following talented Artistes viz:— Charley Fox, the Mackney of New York. Joe Crocker, the original Bob Ridley. Jean Ritter, Premier […] Dancer of America, And Orville Parker, the celebrated Banjo Player, in addition to the following very talented company. D’AUBAN Family, the best Dancers before the Public[…][16]

Orville Pitcher, using the name Orville Parker, starred in his first featured performance in Britain in November 1860 at Wilton’s Music Hall in Whitechapel in a bill that included the D’Auban Family[17]—the performance he later referenced in his 1894 letter to The Era. Wilton’s Music Hall is a rare surviving example[18] of music halls in their original form: large rooms for dining and entertainment built on to existing public houses. Its fame is second only to that of Leeds City Varieties—another rare surviving example of a pub hall—and on a par with that of the New Bedford, long since demolished but immortalised in the paintings of Walter Sickert.[19]

Although we can point to this performance at Wilton’s in November 1860 as the first time that Orville Parker’s name appears on a music hall bill in Britain, we can tentatively point to his having appeared in New York under that name in the spring of 1860. In later years, he would claim in his billing to have once been the proprietor of a troupe called the Hayti Minstrels of New York. There was a troupe of that name active in New York and Worcester, Massachusetts, from March to May 1860, and in at least one advertisement, the manager (not proprietor) of the troupe was listed as ‘O. Parker’. Jumping ahead to September 1861, a troupe calling itself the Hayti Minstrels of New York would perform at a ‘grand fete’ in Birmingham, England. It was in the days leading up to this fete that Orville Parker, appearing elsewhere in the country as a solo artist, would start describing himself as the former proprietor of the Hayti Minstrels. It seems very likely that Pitcher as Parker was the manager of the Hayti Minstrels in 1860 and sought to take advantage of this in his billing once the troupe, reformed or simply back from a hiatus, made its own way to the UK.[20]

From this, we can surmise that, after deserting his regiment in June 1852, he changed his name and made his way to New York City. Whether taking to the stage in blackface was an active attempt to add to his disguise or that was simply a happy byproduct of his decision to take to the stage, we cannot know. However, it is easy to see the extra security hiding behind the mask of blackface afforded him.

What then brought him to England in 1860? For that, I think, we need to look at the other artistes with whom he shared the bill at Wilton’s in November 1860. Charley Fox, Joe Crocker, and Jean Ritter were all former members of a blackface minstrel troupe that had arrived in England in the summer of 1859, ‘Campbell’s American Minstrels, the best and most numerous company that have ever visited the Old World’—indeed, Charley Fox (C.H. Fox) was the troupe’s proprietor alongside a man named Edward Warden.[21]

Charley Fox, described by one journalist as a ‘lank, long-legged comical genius’, had been performing on the New York stage since at least 1855. Of interest to us, remembering that Orville Parker debuted in Britain as a banjo player, Fox was so well known for his banjo-playing skills that by 1856, he was offering lessons in the instrument. By 1859, Fox had joined his future co-proprietor of the Campbell Minstrels, Edward Warden, in Wood’s Minstrels, the most prominent blackface minstrel troupe in New York after the demise of the original Christy Minstrels, on which Wood’s minstrel troupe was modelled. The Christy troupe, led by Edwin Christy and his stepson George Christy, had established the standard blackface minstrel three-act structure in the early 1840s. In 1854, after the Christy troupe’s demise, George Christy partnered with Henry Woods to create the Christy and Wood’s Minstrels, the first iteration of Wood’s Minstrels.[22]

Although I know of no direct evidence to support this, it seems reasonable to suppose that Orville Pitcher, as Orville Parker, had been a pupil of Charley Fox’s in New York and/or a member alongside him and Edward Warden in Wood’s Minstrels before he became the manager of the Hayti Minstrels.

Meanwhile, the Campbell Minstrels was the name given to several blackface minstrel troupes active in New York in this era, some, but not all, of whom were managed by Matt Peel. What claim Fox and Warden had to the Campbell name is not clear, although it is worth noting here that one of the troupes that used the name, ‘Sniffen’s Renowned Campbell Minstrels’, was appearing just down the street from Wood’s Minstrel Hall while Fox and Warden (and Pitcher/Parker?) were with Wood’s Minstrels. This is of extra note as this iteration of the Campbell Minstrels included in its number G.W. ‘Pony Moore, an original Christy minstrel who would make his way to Britain not long after Fox and company and remain prominent in the British music hall scene for many decades. We will encounter Pony Moore again later.[23]

The Fox–Warden Campbell Minstrels troupe toured the British and Irish halls from October 1859 until April 1860, at which time Edward Warden sold his interest in the troupe to Charley Fox. The troupe under Fox’s sole leadership continued to tour until September 1860, at which time it was dissolved and several of its members, including Cox, joined ‘the Ethiopians’, a minstrel troupe with a residency at the Canterbury Hall in London. This latter troupe included and may have been led by G.W. Pell, the founder of one of the earliest blackface minstrel troupes, the Ethiopian Serenaders.[24]

Of note, when the forthcoming appearance of Fox, Crocker, and Ritter at Wilton’s was first announced, there was a specific reference to the Campbell’s Minstrels: ‘first appearance of the principal Comic Members of the Campbell Minstrels, Charley Fox, Joe Crocker, Jean Ritter, and Charles Parker’.[25] ‘Charles Parker’ was almost certainly actually Orville Parker, and, based on this, it seems likely that, after the Hayti Minstrels went on hiatus in May 1860, Orville Parker answered a call from his former teacher to travel to England to join the Campbell Minstrels, appearing with the troupe in the last few months of its tour of Britain and Ireland before joining Cox, Ritter, and Crocker in, first, Pell’s Ethiopians, and then, their appearance as a quartet of performers at Wilton’s.

THIS EVENING, MONDAY, JANUARY 19, First Appearance of the Great Negro Vocalists, Instrumentalists, and Dancers, MESSRS ORVILLE PARKER AND COX, Late Proprietors of the HAYTI MINSTRELS. To Conclude each Evening with The GREAT and GORGEOUS PANTOMIME of HARLEQUIN MAGGIE LAUDER, AND THE MAGIC BAGPIPES![26]

Charley Fox returned to New York at the end of December 1860.[27] It may well be that the other former Campbell Minstrels intended to follow him at some later date. However, if that was the case, it was not to be. The outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861 found Orville Pitcher—using the name Orville Parker—boarding in Liverpool, the port city that he, for obvious reasons, would make his home for the duration. As the city was heavily involved in the cotton trade and many of its American residents were either from the South or at least southern-leaning, it was a prominent centre of support for the Confederacy—a Liverpool shipyard built the Confederate commerce raider, Alabama—which makes one wonder how well the New Yorker Orville Pitcher fit into the expatriate community there. However, as he would spend most of the year touring, it was perhaps not a significant issue. He would, of course, have no thought of returning home, which would only invite the attention of the US Army.[28]

Although Pitcher spent some of the years 1861–1865 touring as a solo performer, he also formed two significant partnerships during this time. The first, in August 1862, was with the Scottish blackface minstrel, Abraham Cox (A.A. Cox). The pair would tour, together with Cox’s wife, who was a singer of Scottish ballads, for much of the latter half of 1862 and the first two months of 1863, sometimes claiming to both be the former proprietors of the Hayti Minstrels.[29]

The second significant partnership that Pitcher would form in this period, one that he would feature in his billing for many years to come, would be his appearance in 1864 in a season of performances with one of the several blackface minstrel troupes touring Britain that called itself the ‘Christy Minstrels’ in imitation of the New York original. The significance of this troupe was that it was led by original Christy Minstrel, Pony Moore, whom we met briefly earlier, and would, in later years, be known as the Moore and Burgess Minstrels, arguably the troupe that, more than any other, was responsible for the continued popularity of blackface minstrelsy in Britain into the early Twentieth Century.[30]

(As an aside: Joe Crocker and Jean Ritter, Pitcher’s erstwhile colleagues in the Campbell Minstrels and at Wilton’s in 1860, would also, in 1865, become members of Pony Moore’s Christy Minstrels, although by this time, Pitcher had himself moved on.[31])

In his personal life, the most significant event in the life of Orville Pitcher in these years was his marriage under his own name in 1865 in Liverpool to Charlotte Sutton, the 25-year-old daughter of a Norfolk farmer. As stated above, the registration of this marriage is one of the pieces of evidence we have that connects Orville Pitcher with Almon Pitcher. Alas, I have to date found out little about this marriage. It seems not to have produced any children (or at least none that survived infancy). The couple were still together and traveling together at the time of the 1881 England census, and we have tentative evidence—as we will see below—that Charlotte met Pitcher’s family in New York in 1870 or 1871. However, by 1908, Orville Pitcher was travelling alone. That is as much as I have been able to discover to date.[32]

The second half of the 1860s would be a busy time for Orville Pitcher, still performing as Orville Parker, as he toured his, by this time, well-honed solo act around the British halls. In common with many solo blackface comedians (as opposed to solo blackface singers and dancers), the centrepiece of Pitcher’s act as Parker was his turn as a ‘stump orator’, in which he gave a mock political speech in blackface and using what blackface minstrels passed off, falsely, as ‘negro’ dialect. A flavour of this type of performance can be gained from the title of one of the stump oration pieces performed by Charley Cox, Pitcher’s erstwhile teacher and colleague: ‘Dar’s No Discount on Dat’.[33]

Although never reaching the top rank—or top billing—Pitcher was also never without work and always a featured performer. He could fairly be described as a success. I think it is to his sense of this himself that we can ascribe his decision, in the early summer of 1870, to finally return to America his family, a reunion—or confrontation—that had been a long time coming.

EAGLE HALL. Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, 19, 20, 21. ORVILLE PITCHER. GRAND COMIC ENTERTAINMENT, Entitled “E PLURIBUS UNUM”.[34]

In July 1870, Orville Pitcher debuted under his own name at Eagle Hall in Ogdensburg in upstate New York, 30 miles from the Pitcher family home in Gouverneur. He and Charlotte had landed in Quebec the previous month and likely made their way to upstate New York along the St Lawrence River, a far easier trip than the overland journey from New York City, the main entry point to the US for travellers from Europe.[35] This alone made it likely that this trip was explicitly a trip home.

What we cannot know is to what extent Pitcher had communicated his intent to his family in advance, or, indeed, to what extent he had been in contact with his family since his incarceration in the Western House of Refuge back in 1850. That he debuted under his own name after at least 10 years performing as Orville Parker is of obvious significance. It is hard to believe that he would have done so had he not been confident that his success in England had, in some sense, atoned for his sins of the past. From the other side, that of his parents, we can point to the fact that he was named as a beneficiary in his father’s will, filed after Almon Pitcher’s death in 1882. As far as him being a fugitive from the US Army went: had he received some indication that they were no longer looking for him, or had he perhaps used some of the money he had earned in England to buy his way out of the situation? Alas, at this remove, we cannot know.[36]

At the same time, this was no homecoming: the Pitchers would be back on the road by the autumn of 1870, with Orville Pitcher appearing under his own name in Otsego—which, significantly, was on the road from upstate New York to New York City. Orville Pitcher was no more interested in becoming a farmer in 1870 than he had been in 1849.[37]

The great London mimic (just arrived), MR. ORVILLE PARKER. Mr. Parker sings and acts an entirely new collection of character songs.[38]

By February 1871, Orville Pitcher had returned to the New York City stage under his old stage name/identity, Orville Parker. At first glance, it may seem strange that he had reverted to calling himself Parker. However, it should be remembered that Orville Parker was the name that New York City theatre bookers knew him under from his earlier appearances with the Hayti Minstrels and perhaps Wood’s Minstrels. More than this, all the notices and testimonials from his performances in Britain—his resume as an artiste—were in that name. In support of this, we can point to his billing at this time, which identified him as a ‘London mimic’. He was making use of his success in Britain and his unique selling point as an ‘international’ artiste to re-establish himself and, critically, make himself and his new act known personally to New York theatre managers and bookers in preparation for dropping the Parker stage name and reclaiming his own.

He returned once again to using his own name in Baltimore in Washington, DC, in May 1871 and then went on to Washington, DC, and, by July, Cleveland, Ohio—an out-of-town tryout. If his notices are to be believed, he commanded a salary of $150–200 a week, the equivalent of a year’s salary for a farmhand, something of which he was surely acutely aware. Interestingly, he still billed himself as an ‘English comique’, continuing to draw on his unique selling point as an international artist (did he put on a fake English accent? It must have helped that he had an English-born wife at his side). Also of interest to us here was that he was at the same time trying out a new act, one that featured ‘Black and White Characters, with Songs, Dances, Banjo Solos, Stump Speeches, &c.’ I will return to this development later.[39]

By December 1871, he had returned to New York and opened at Hooley’s Opera House in Brooklyn under his own name and the billing ‘an English celebrity’. May of the following year found him performing at the ‘birthplace of vaudeville’, Tony Pastor’s Opera House in the Bowery, Lower Manhattan. It would seem that he was now as successful in his home state as he had been in England. However, within a few months, he and Charlotte would be back in England.[40]

FUN WITHOUT VULGARITY,—On Wednesday and Thursday evenings last Mr. Orville Pitcher, “the American mimic, vocalist, dancer, humorist, comedian, &c.,” gave entertainments, entitled “Lights and Shades,” and comprising sketches of peculiar people met with every day, illustrated by appropriate costumes, in the Assembly Room of the Corn Exchange. Mr. Adam R. Riche presided at the pianoforte, accompanying the songs and giving a choice selection of operatic solos, overtures, &c. The entertainments were very good, but the audiences were rather limited.[41]

What brought Orville Pitcher back to Britain? Was this always the plan? Was the return to New York State always going to be only a visit, albeit a long one? It’s impossible to know. On the one hand, having reconciled with his family and regained his name, there was every reason for him to stay and perform in New York City. On the other hand, there was Charlotte to consider, who had her own family to think about, and the fact that, in New York, there was only so long he could continue to draw on the unique selling point of being an ‘English’ performer when he was not.

Regardless, if he thought he could return to England and just pick up where he had left off, but now using his own name, he was in for a rude awakening. The problem was, of course, an obvious one; indeed, it was the problem he had faced in New York: Orville Pitcher had no name recognition. After his return, there followed a period of several years in which he would appear at different times under his own name and under his old stage name, Orville Parker, presumably falling back on the latter when he could not obtain a booking under his own name.[42]

However, his desire to reclaim his old name was obvious in his dogged persistence with using it as often as bookings allowed—which became more frequent as the years passed. We can also see an attempt to reclaim his own face in the act that he performed both as Orville Pitcher and Orville Parker in this period: Lights and Shades.

The delineation of various eccentric characters we meet in every day life, formed the first part of the programme[...]His change of character was very rapid and so perfect as sometimes to cause a doubt that more than one performer was engaged. The second part consisted of negro characters with a stump speech in which Mr. Pitcher neatly introduced the topics of the day.[43]

Setting aside the unfortunate name of the act, it is clear that, with this act combining white and blackface characters, Pitcher was trying to step away from blackface minstrelsy, or at the very least, establish an additional stage persona separate from it. I see in this an attempt to finally set aside a mask (blackface makeup) that he felt he no longer needed now that he had atoned for the sins of the past (at least in the eyes of his family) and reclaimed his own name. What he wanted was to perform under his own name and show his own face.

Alas, events would show that, although in time, as in the US, audiences would accept him under his ‘new’ name, they would not accept him as anything other than a blackface minstrel. He could not go against the audience’s taste. He was not alone in this; I have already covered the careers of other white performers of blackface minstrelsy who found that, whatever their own ideas, once they began to perform in blackface, that was the only way audiences wanted to see them.[44]

In time, the ‘Lights and Shades’ act would develop into the ‘Lights and Shades Combination Company’, critically, with a full cast of performers playing the various [white] characters, and Pitcher restricting himself to performing his familiar topical stump speech in blackface. That company folded in 1884. By that time, Pitcher had been a stage performer for at least a quarter century.[45]

MR. ORVILLE PITCHER, Genuine American Ethiopian Comedian, who will introduce Plantation Songs and Dances, Banjo Specialities, Burlesque Orations, &c.[46]

Orville Pitcher would continue to perform in Britain for another 25 years. During that time, he would both perform in and manage one of the famous Poole family Myrioramas, the pre-cinema entertainments of changing painted and later photographic scenes that were many British audiences’ first introductions to the world beyond these shores.[47] He would form and manage at least two more variety troupes modelled on the ‘Lights and Shades Combination Company’, as always, reserving the role of blackface stump orator for himself. Having played in Pony Moore’s Christy Minstrels in 1864, 30 years later, he would perform with the troupe again under the name by which it is more famously known, the Moore and Burgess Minstrels. He would enter into an argument with George Ware over the true authorship of the song that he performed at Wilton’s Music Hall, and after Ware died, continue the argument with Ware’s son. Having seen out the end of the nineteenth century playing in Poole’s pre-cinema entertainment, he would, by the end of the first decade of the new century, be sharing the same bill as screenings of silent movies.[48]

He would, in short, in a career spanning 50 years, see the rise and ascendency of music hall and its evolution into variety and still be there to witness the birth of the new form of entertainment that would ultimately replace it. All the while, he would continue to perform in blackface. Given his attempts to come out from behind that mask after he reconciled with his family and put his army desertion behind him, it is with some irony that, in the latter years of his career, he found that he needed it, as it served to hide his advanced age.

Claiming to be 62, but in reality, aged 76, Orville Pitcher left Britain for the final time in May 1911. This was no retirement, however, as, by August of that year, he was to be found performing in Green Bay, Wisconsin, billed as an old time minstrel comedian.[49]

Fittingly, it is at this point that he disappears from the records.

Jamie Barras, November 2025.

Back to Staged Identities

Notes

[1] ‘The Whole Hog or None’, The Era, 20 January 1894. A week after The Era published Pitcher/Parker’s letter, it published a response from George Ware, the man credited with writing ‘The Whole Hog or None’ by The Era, in which Ware stated that the song was nearly 50 years old, and questioned where Tom Norton got it to give to Parker/Pitcher. Just to complicate things further, it’s possible that the two men were talking about two different songs with the same name. ‘The Whole Hog or None’, The Era, 27 January 1894. Discussion of different versions of the song: https://folksongandmusichall.com/index.php/whole-hog-or-none-the/, accessed 27 October 2025.

[2] ‘State News’, Utica Free Press (Utica, NY), 2 December 1882.

[3] The history of the Pitchers can be assembled from genealogical information. See, for example, Almond Pitcher (1798-1882) | WikiTree FREE Family Tree, accessed 30 October 2025. I will address the question of how we know this Orville Pitcher is ‘our’ Orville Pitcher in the main text.

[4] Orville Oscar Pitcher and Charlotte Sutton’s marriage registration, 8 July 1865, St Brides, Liverpool, Liverpool, England, Church of England, Marriages and Banns, 1754–1935. ‘Orville O. Pitcher of London, England’ named in Almon Pitcher’s will, probate date 18 January 1883: New York, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999. Ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 25 October 2025. Orville Pitcher, arrival, NY, SS Caledonia, 22 May 1911, New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 25 October 2025.

[5] This information can be assembled from US Federal Census returns for Almon Pitcher (1840 and 1850, Boonville, Oneida, and Gouverneur, St Lawrence, New York State, respectively) and Orville Pitcher (1850, Rochester, New York State), ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 25 October 2025.

[6] ‘The City of Rochester—Western House of Refuge—Crops, &c.’, New-York daily tribune (New York, NY), 6 October 1849.

[7] ‘The Greatest Reform School in the World: A Guide to the Records of the New York House of Refuge’, New York State Archives, 1989, Chapter ‘A Brief History’, 4–5, https://www.archives.nysed.gov/sites/archives/files/res_topics_ed_reform.pdf, accessed 30 October 2025.

[8] 1846 New York law: Merril Sobie, Pity the Child: The Age of Delinquency in New York, Pace L. Rev., 2010, 30, 1061–1089. The number of original inmates of the Western House of Refuge of Rochester is given here: ‘Institutions for the Reformation and Education of Juvenile Criminals’, New-York daily tribune (New York, NY), 15 September 1854.

[9] Frederick Douglass, ‘Gavit’s Original Ethiopian Serenaders.’, The North Star (Rochester, NY), 29 June 1849. Quoted here: https://utc.iath.virginia.edu/minstrel/miar03at.html, accessed 30 October 2025.

[10] https://www.visitrochester.com/things-to-do/history/frederick-douglass/, accessed 30 October 2025.

[11] Information on the Serenaders: Notice of performance, Utica Daily Observer (Utica, NY), 24 May 1849. D.E. Gavit was the New York publisher of ‘A Choice Collection of Original and Selected Whig Songs’: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/efts/ARTFL/projects/lincoln/lincoln.bib.html. There was a Daniel E. Gavit, photographer, active in New York in this period: https://pioneeramericanphotographers.com/tag/daniel-e-gavit/, accessed 30 October 2025.

[12] See Note 9 above.

[13] Frederick Douglass, ‘The Hutchinson Family.—Hunkerism’, The North Star (Rochester, NY), 27 October 1848. Quoted here: https://utc.iath.virginia.edu/minstrel/miar03bt.html, accessed 31 October 2025. The Hutchinson Family, who were white, were a cappella singers of African American spirituals and supporters of the abolition movement; Douglass was reacting to a negative review of their performance that slighted the origins of the songs in an attack on the abolition movement.

[13] https://www.visitrochester.com/things-to-do/history/frederick-douglass/, accessed 30 October 2025.

[14] Resources on the early history of blackface minstrelsy: https://library.pitt.edu/blackface-minstrelsy, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/blackface-birth-american-stereotype, https://utc.iath.virginia.edu/minstrel/mihp.html, accessed 30 October 2025.

[15] The details of Orville Pitcher’s enlistment and desertion can be found here: entry for Orville O. Pitcher, 21, ‘farmer’, enlisted Sackett Harbor, New York, 16 February 1852, deserted 24 June 1852, U.S., Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798–1914, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 3 November 2025.

[16] ‘Advertisements’, East London Observer, 24 November 1860.

[17] https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/4449ab20-ead3-0133-773c-00505686a51c, accessed 1 November 2025.

[18] https://wiltons.org.uk/, accessed 1 November 2025.

[19] https://leedsheritagetheatres.com/city-varieties-music-hall/, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/walter-richard-sickert-the-new-bedford-r1136015, accessed 1 November 2025. One of the early proprietors of Leeds City Varieties, back when it was still known simply as the Varieties, was Charles Morritt, whose story I tell here: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-they-see-nothing-at-all, accessed 1 November 2025.

[20] Parker’s first time claiming to be the former proprietor of Hayti Minstrels: ‘Public Announcements: Grainger Hotel Concert and Supper Rooms’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 16 September 1861. Hayti Minstrels performing in Birmingham, England: ‘Public Amusements: Grande Fete at Molineux Gardens’, Birmingham Daily Post, 18 September 1861. ‘O. Parker’, manager of the New York Hayti Minstrels: ‘Amusements: Hayti Minstrels’, New York Herald (New York, NY), 5 March 1860. Hayti Minstrels in Worcester, Mass.: ‘City and Country: The Hayti Minstrels’, Worcester Daily Spy (Worcester, Mass.), 2 May 1860.

[21] Charley Fox left New York ‘for Europe’ in August 1859: ‘Amusements: 444 Broadway’, New York Herald (New York, NY), 4 August 1859.

[22] C.H. Fox at the Bowery Theatre, 1855: ‘Amusements: Bowery Theatre’, New York Dispatch, 11 February 1855. ‘lank, long-legged...’: 'The Story of the Banjo', New Haven daily morning journal and courier (New Haven, Conn.), 25 October 1895. Fox and Warden in Wood’s Minstrels: ‘Amusements: Wood’s Minstrel Building’, New York Herald (New York, NY), 23 May 1859. Christy Minstrels and the three-act formula: ‘History of Minstrel Shows’, https://black-face.com/minstrel-shows.htm, accessed 1 November 2025. For an academic treatment, see: Robert E McDowell, “Bones and the Man: Toward a History of Bones Playing”, Journal of American Culture, 1982, 5: 38-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-734X.1982.0501_38.x, accessed 7 April 2025. Wood and George Christy: ‘Amusements: Geo. Christy and Wood’s Minstrels’, New York Herald (New York, NY), 10 March 1854.

[23] Pony Moore and Sniffen’s Campbell Minstrels: ‘Amusements: 444 Broadway’, New York Herald (New York, NY), 6 February 1859. Pony Moore: https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/v/object-511082/moore-burgess-minstrels/, accessed 1 November 2025.

[24] First appearance of Charley Fox’s Campbell’s American Minstrels in Britain: ‘Royal Surrey Theatre’, Morning Advertiser, 8 October 1859. Ritter in the company and ‘C.H. Fox’: ‘The Campbell Minstrels’, Kentish Express, 11 August 1860. Crocker in the company: ‘Advertisements and Notices: Messrs Crocker and Ritter’, Era, 2 December 1860. Warden leaves the troupe: ‘Advertisements and Notices: Mr Edward Warden’, Era, 8 April 1860. G.W. Pell and ‘The Ethiopians’: ‘Canterbury Hall Concerts’, Sun (London), 2 November 1860. G.W. Pell: https://thejubaproject.wordpress.com/featured-performers-documents/parsing-the-documents/hyperdocuments/ethiopian-serenaders-at-vauxhall/portrait-of-g-w-pell/, accessed 1 November 2025.

[25] ‘Advertisements and Notices: ‘Wilton’s Magnificent New Music Hall’, Era, 12 November 1860.

[26] ‘Amusements’, Daily Review (Edinburgh), 19 January 1863.

[27] ‘Personal’, New York Herald (New York, NY), 1 January 1861.

[28] Pitcher gave his name as Orville Parker in his 1861 England Census return: Orville Parker, ‘musician’ of New York, US, Liverpool district, 1861 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 25 October 2025. Liverpool and the Confederacy: https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/liverpools-abercromby-square/abercromby-southern-club, https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/american-civil-war/liverpool-and-american-civil-war, accessed 2 November 2025.

[29] Cox and Parker/Pitcher team up: ‘Amusements: New Amphitheatre and Concert Hall’, Leeds Times, 9 August 1862. Claim to both be former proprietors of Hayti Minstrels: See Note 27 above. The Coxes, husband and wife: ‘Entertainments, &c.: Tyne Concert Hall’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 25 November 1862. Last Cox–Parker performances together: ‘Amusements: Royal Alhambra Theatre’, Daily Review (Edinburgh), 21 February 1863. Abraham Cox: ‘Public Amusements: The Alexandra’, North Briton, 22 October 1864.

[30] Parker in the Christy Minstrels: ‘Christy’s Minstrels’, Liverpool Daily Post, 26 April 1864. Moore and Burgess Minstrels: see Note 24 above, final reference.

[31] Crocker and Ritter in the Christy Minstrels with Pony Moore: ‘Theatrical and Musical: Standard’, Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, 22 July 1865.

[32] Marriage and Charlotte Sutton’s father’s occupation: See Note 4 above, first reference. Year and location of Charlotte Sutton’s birth: entry for Orville Pitcher ‘comedian’ and Charlotte Pitcher in 1881 England Census, St Pancras, London. Orville and Charlotte Pitcher travelling the North America together, 1870: entry for Orville Pitcher and Charlotte Pitcher, passenger lists, SS Germany, arrived Quebec 22 June 1870, Canada, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1865-1935. Orville Pitcher travelling alone in 1908: entry for Orville Pitcher, passenger lists, SS St Paul, leaving Southampton, 22 February 1908, UK and Ireland, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890–1960. Ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 25 October 2025.

[33] Pitcher as Parker ‘stump orator’: ‘Amusements: Brown’s Royal Music Hall’, Glasgow Evening Citizen, 29 July 1869. Charley Fox’s stump orator act: ‘Amusements: Wood’s Minstrel Hall’, New York Sunday Dispatch, 26 April 1864.

[34] ‘Eagle Hall’, Daily Journal (Ogdensburg, NY), 21 July 1870.

[35] Entry via Quebec, June 1870: See Note 33 above, third reference.

[36] See Note 4 above, second reference.

[37] ‘Town and Country News: More Shows’, Oxford Times (Oxford, NY), 26 October 1870.

[38] ‘Amusements: Globe—728 Broadway’, New York Herald (New York, NY), 26 February 1871.

[39] Orville Pitcher, Baltimore, ‘Black and White Characters’: ‘Amusements: Holiday Theatre’, Baltimore Sun, 8 May 1871; Washington, DC, and $200 a week: ‘Amusements: Metropolitan Hall Variety Theater’, Critic and Record (Washington, DC), 23 May 1871. Cleveland, Ohio, and $150 a week: ‘Amusements: Theatre Comique’, Evening Post (Cleveland, OH), 11 July 1871.

[40] ‘Announcements’, Brooklyn Union, 11 December 1871. ‘American Theatricals: Tony Pastor’s Opera House’, Era, 2 June 1872. Tony Pastor and Vaudeville: https://archives.nypl.org/the/21700, accessed 2 November 2025.

[41] ‘Fun Without Vulgarity’, Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette, 10 September 1872.

[42] As Orville Parker presenting Lights and Shades: ‘Metropolitan Music Hall’, London and Provincial Entr'acte, 30 November 1872.

[43] ‘Royston—Entertainment’, Cambridge Independent Press, 21 September 1872.

[44] https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-cuckoos-and-nightingales, accessed 2 November 2025.

[45] Lights and Shades Combination Company: ‘Public Notices: Shodfriars’ Hall, Boston’, Boston Independent and Lincolnshire Advertiser, 06 September 1884.

[46] ‘Public Notices: Exchange Hall, Spalding’, Spalding Guardian, 6 September 1890.

[47] Joe Kember and John Plunkett, 'Panoramas, Dioramas, and Public Hall Spectacles', Popular Visual Shows 1800–1914: Picturegoing from Peep Shows to Film (Oxford, 2025; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 Apr. 2025), https://doi.org/10.1093/9780191944987.003.0004, accessed 2 Nov. 2025. Pitcher in the George Poole Myriorama entertainment: ‘Poole’s Myriorama’, Jersey Express and Channel Islands Advertiser, 11 August 1885. Manager: ‘Visit of Poole’s Greatest Exhibition’, Southern Echo, 1 October 1888. Back in the Myriorama ten years later: ‘Poole’s Myriorama’, North British Daily Mail, 27 September 1898.

[48] Own troupes: see Note 47 above and ‘Exhibition Buildings, York’, Yorkshire Gazette, 11 April 1903. In Moore and Burgess Minstrels: ‘Musical Tableaux Vivants: “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”’, Eastbourne Gazette, 14 August 1895. Ware argument: see Note 1 above, and response from Ware: ‘Whole Hog or None’, Era, 27 January 1894. Picking up argument with Ware’s son: ‘Whole Hog or None’, Era, 11 January and 18 January 1896. Performing on same bill as silent movies: ‘Glasgow: Hengier’s, Ltd’, Era, 11 March 1911.

[49] Orville Pitcher leaving Britain for the final time: see Note 4 above, final reference. In Green Bay: ‘Bijou Theater’, Green Bay Gazette, 31 August 1911.

Western House of Refuge, Rochester, New York. Image courtesy of the Huntington Library. Used with permission.

Orville Parker's first featured performance in Britain, November 1860. East London Observer, 24 November 1860. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Charley (C.H.) Fox, Wood's Minstrels. Showing the character that Orville Pitcher would also play for over 50 years. WSU Libraries Digital Collections. No known copyright holder.

Pitcher as Orville Parker, New York, 1871. New York Herald, 27 February 1871. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Pitcher as Orville Pitcher, New York, 1872. New York Dispatch, 3 March 1872. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Pitcher's Merry Company. Spalding Guardian, 6 September 1890. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Tony Pastor's Opera House, the birthplace of vaudeville. Image created by the New York Public Library. No known copyright holder.