Intolerance

Jamie Barras

MANCHESTER CENTRAL I.L.P. SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 30, CLARION CAFE, 7.46 p.m. Speaker: Dr. LINCOLN STERNE. Subject: “Intolerance”.[1]

Abraham Lincoln Sterne (1864–1942) was born in Washington, D.C., in December 1864, one month after his namesake had won re-election by a landslide on the strength of a string of Union victories and the real hope that the Civil War would be over by the spring. His father, Hungarian-German immigrant Joseph Sterne, died while Lincoln was still an infant, and Lincoln grew up in New York in the childhood home of his mother, Helen Sterne née Weigart, who was born in what was then Prussia. His maternal grandfather, Benjamin Weigert, was a doctor, as was his Uncle Louis, and this seemed to be the path down which young Lincoln was headed, as by 1880, aged 15, he had begun work as a druggist’s apprentice. However, ultimately, dentistry was the profession he took up.[2]

He also travelled extensively, having made at least two trips to Germany and one to Russia by his mid-twenties.[3] In 1892, on his way back to the USA from Russia, he stopped off in England, and there he met Julia Minna Reunert, the daughter of a prosperous German immigrant; a courtship ensued,[4] and Sterne abandoned his plans to return to the USA, settling with his new bride in Manchester in the North-West of England. He opened a dental practice at 13 St Ann Street, in the heart of the city’s commercial district. A keen sportsman, while in Berlin, he had joined BSV 78, Germany’s oldest swimming club.[5] Eager to make a similar impact on the local sporting scene, in early 1894, he volunteered to apply his Yankee know-how to helping establish an American baseball presence in the district.

He didn’t know it, but in doing so, he was stepping into a different kind of Civil War.

Since the challenge was originally given the National Rounders Association has changed its name to “The English Baseball Association”, although still playing the old game of rounders. I am glad to state, however, that the matches referred to will be played according to the genuine or regular baseball rules.[6]

What makes baseball ‘baseball’? In 1890s Britain, this was a subject of heated debate (it can be argued that it still is). Famously, in the previous decade, US sporting equipment manufacturer Albert Spalding set about promoting baseball across the world as a sport native to the USA, played under a set of rules written in the USA, rules that, not coincidentally, required the use of standardised equipment that the Spalding Bros. company sold.[7]

Spalding had played a double role in the first tour by American baseball clubs of England in 1874, as a player and a tour promoter. The tour was the brainchild of English-born team owner Harry Wright and was generally viewed as a failure. Writing nearly two decades later, fellow baseball booster Newton Crane—from whom we will hear much here—explained this failure as being due to the focus on exhibition over instruction: with no knowledge of the rules, ‘bewildered spectators’ could make no sense of what they were watching.[8i]

There was evidence in support of this view in the experience of the first known “base ball club” in Britain, which predated the Wright tour by several years. In 1870, a “base ball club” was founded in Dingwall, in the Scottish Highlands, by 30 young men of the town who received their instruction in the game from 20-year-old Andrew Keith ‘A.K.’ Brotchie (1850–1926), a local man who had spent his formative years in Boston, Mass. Alas, when Brotchie returned to the US the following year, interest in the game in the local area petered out—without Brotchie there to guide them, local players lost any sense of how to progress the game.[8ii]

We can extend this argument to the only American baseball scene in Britain known to have been directly inspired by the Wright tour. In 1876, two years after the Wright tour, the Leicester Base Ball Club was founded. This was the beginning of a brief flowering of the sport among the mill workers of the town as, uniquely, a winter complement to the summer sport of cricket. The scene, which never involved more than four clubs and lasted only two years, grew out of a recognition that American baseballers had something to teach English cricketers about the art of fielding. In a sign of things to come for American baseball in Britain, its chief backers were mill owners keen to get their workers involved in the sport in the belief that a happy workforce was a productive workforce. Its failure was, once again, the result of having no way to progress beyond simply learning how to play due to the lack of contact with experienced players.[8ii]

Elsewhere, sportmen faced with the same problem—no way to learn the American game without American experts—arrived at a different, and longer-lasting solution: to take inspiration from what they saw and come up with their own sport. The first game of the Wright tour in England was an exhibition match at Liverpool. Some of those spectators, bewildered or not, evidently liked what they saw, as by the late 1870s, rounders had made a comeback in the district.

The Rounders Association are anxious to promote the extension of the game generally, especially in the neighbouring towns of Lancashire, and with this view, I am instructed to write that we shall be glad to furnish all information, laws of game, &c., free to anyone who writes to the address given at the foot of this letter.[9]

This is not the place to debate whether rounders is the direct ancestor of baseball; it is generally accepted as such,[10] but all that matters to us here is that a British spectator of a game of baseball in the late Nineteen Century would have recognised something of the game they played as a child in what they were seeing. Indeed, in searching for a shorthand way of describing American baseball to British readers unfamiliar with the sport, from the very start, the British press would compare it to rounders, although sometimes allowing for it be to an ‘improved’ or more ‘scientific’ form of the children’s game[11]—descriptions I will return to. It is a short step from that moment of recognition to a revival of interest in the game of rounders as a sport for adults.

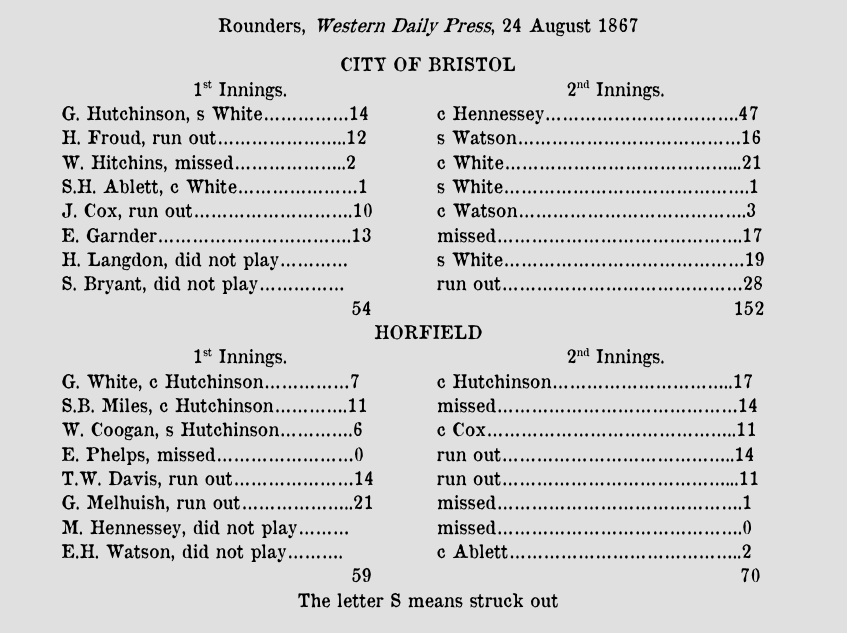

It is important to note here that this is not to say that rounders was not played by adults as a pastime before this time; it is simply to say that interest in the possibility of the game as something more than a pastime dates from this period. The first attempt to turn rounders into a sport can be traced to Bristol in 1864, with the founding of The City of Bristol Rounder Club (note: ‘rounder’ singular, a peculiarly pedantic application of English grammar that would soon be abandoned). This would later become The City of Bristol Rounder and Cricket Club, and although it was defunct by 1870, rounders continued to be played in the city and neighbouring county of Gloucestershire in some form into the 1880s; its fate after that, we will discuss below. We have scorecards for two games (see gallery below for one scorecard); they show an evolving game, with teams of six or eight players, two innings, and players being run out, caught out, or struck out—although it is not clear if the latter is being struck out as we would understand it or a form of tagging, i.e., base-runners being struck with a thrown ball. Based on the number of runs scored, evidently, each inning ended when all the opposing players were put out, or else there was no player to come to bat, the only players not out being on the ‘bases’ or ‘posts’ (this appears to be the meaning of ‘missed’ in the scorecards). The curiously low number of players in each team—was there no one in the outfield, or were the bases not covered?—seems like a misstep. This may explain why the scene did not grow. It also seems the case that the Bristol club did not write down a set of rules to disseminate.[12i]

There is also evidence of a two-innings version of the pastime being played in Cardiff, South Wales, from 1870 onwards. This development is of particular interest as the teams were formed of blue-collar workers—engineering firm employees and shipwright apprentices—in contrast to the white-collar Bristol scene. However, in common with Bristol, there seems to have been no attempt to codify the rules.[12ii]

This lack of attempts to grow the game in Bristol and Cardiff stands in contrast to the near-contemporary but seemingly independent rounders scene in another port city on the west coast of Britain, Liverpool. To explain the differences, it is instructive to look at the history of the Liverpool Rounders Club (LRC). The club was founded as The Duke of Edinburgh Rounder and Quoit Club in 1873—a year before the arrival of Wright’s baseball tour. However, it was not until 1877, the year of its name change, that it could boast of being part of a local rounders scene that included several other clubs playing in local parks. Of note is that a scorecard from that same year shows that the LRC played a version of the sport that featured teams of 11 players playing across three innings in the cricket mold. For a concise history of the development of the sport in this early stage, readers can do no better than the account given by William Morgan (1923–2015), chronicler of baseball in Britain, its first significant historian, and member of the British Baseball Hall of Fame, who documented this period of history in his Baseball Mercury magazine in the 1980s.[12iii]

The rounders scene in Liverpool continued to grow across the late 1870s and early 1880s. Critical to understanding subsequent developments is appreciating that this was a grassroots movement. Clubs were formed, which led to the formation of more clubs. Word spread, interest grew, and then, and only then, was a governing body formed, the Liverpool Rounders Association (LRA). Here, we see a pattern of evolution that mirrors that of other sports in the UK in the late Nineteenth Century. The LRA was formed no later than February 1882,[13] but its Big Bang moment, just like that of Association Football, was its creation of a standardised set of rules that would allow the spread of the game without the need for new teams to have had experience of playing the game against established teams. The LRA announced this development in letters written by its secretary, Liverpool businessman W.H. Hivey (William Henry Hivey (1852-1950)), and sent to the local press in the summer of 1883. Arguably, the most significant aspect of these letters, and indeed, the whole development, was that, in discussing the origin of the new rules, the LRA acknowledged in writing the role of American baseball in the growth of rounders as a sport.

Sir,—May I trespass on your space to bring under the notice of your very numerous readers a revival of an old school game, viz., Rounders, under a new form, governed and ruled by laws as to bowling, batting, &c., as in cricket, these laws being mainly founded on a very popular American game called Base Ball?[14]

The first evidence I can find of an attempt to codify the rules of rounders in Liverpool in this period is a game played by the LRC (at this stage, still calling itself the Duke of Edinburgh Rounder and Quoit Club) in June of 1875, as reported to the press in the form of a letter from the club secretary.

To allow for scoring, &c., the following conditions were agreed to:—A player to run the three “bases” (without being “knocked out”) to score a point. A “catch” to be the batsman’s “out” only, and when all but one are put out, the other side to go “in”. Each side to have an equal number of innings.[15]

The teams each had six players—echoes of the Bristol variant, but something that the Liverpool would soon, wisely, abandon—and there were three innings. The game lasted 1 hour and 30 minutes. See scorecard at the end of this article. Also of note is that each player continued to have turns at bat until either they were put out or the inning ended—the latter implying that the player was at one of the bases when their last teammate was put out. Again, this is reminiscent of the Bristol variant.

The use of the word “bases” and a “point” being a complete circuit of the bases aside, there is little here that is drawn from American baseball. Of the many striking differences, the one that is most likely to have an impact on differences in play between this and the American game is the fact that the ‘batsman’ can only be put out by a catch, i.e., there is no striking out (note, however, that once they become a base runner, the player can be ‘knocked out’, i.e., run out or tagged out). The lack of striking out is a recipe for a batsman opting to avoid swinging at any ball he does not view as likely to lead to a good hit and, consequently, potentially spending a long period at the plate, greatly slowing down the pace of the game.

Although I do not propose to go through all the similarities and differences between rounders as played by the LRA and American baseball—others have already done a far better job of that than I ever could[16]—it is instructive to highlight what the LRA did and did not take from the American game in formulating its own rules, compared with this early LRC attempt at codifying the rules of rounders in Liverpool.

In terms of things the LRA took from the American game, it should come as no surprise, given the discussion above, that the LRA’s 1883 rules added tagging out of the batsman and introduced the idea of a maximum number of ‘good balls’ that the batsman could choose not to swing at before he would have to either swing at the next ball or run regardless. In addition, this was initially set at three ‘good balls’, although it would later be reduced to two ‘good balls’ to further speed up the game.

In highlighting what the LRA kept from these early LRC rules in ‘defiance’ of American practice, we can focus on the idea of a small number of innings in which all players bat again and again until put out or are left stranded on a base[17] when the last of their teammates is put out—i.e., there is no three-outs-all-out rule, something that subsequent events, discussed below, would show was viewed as a red line by the LRA. In common with later LRC practice, the LRA would also settle on teams of 11 players.[18] It is useful to couple this with an innovation in the LRA rules that is neither in the American rules or the early LRC approach: the idea that a run is scored each time a player reaches a new base, i.e., simply reaching first base puts a run on the board, while going all the way around all four bases results in a score of 4 runs. Taken together, these elements lead to a key, and in my view, critical perceptual difference between games of rounders under the LRA rules and games of baseball under the American rules: the opportunity for extended periods of uninterrupted play, high scores, and high scoring rates.

…it should be mentioned that the non-productiveness of the bowling—or rather “pitching”—does not find room for any defensive play, for the hitter simply declines to strike the ball, which—occasionally eight or nine times in succession—falls into the hands of the back-stop merely to be chucked again to the pitcher. If these features do not come under the description “monotonous” I don’t know what can![19]

In the long history of attempts to introduce American baseball into England, nothing has taxed English spectators more than learning to appreciate the sight of a good battery going to work under a three-outs-all-out system. In the USA, fans, from the earliest days of the game, learned to revel in the tension that built while they waited for one of their team’s batters to make contact with the ball; like a boxing match in which the more scientific fighter holds their punches, it is the anticipation of the moment when they finally cut loose that drives the enjoyment. English spectators, used to the steady run scoring of cricket, and revelling rather in the variety of strokes deployed by the batsman and the turning of the ball by the bowler, found games that consisted largely of, as the British press had it, the pitcher and catcher throwing the ball to each other. . . monotonous. As the above quote, from an August 1874 edition of the Lancaster Gazette, shows, this was an issue that English observers had with the game from the first. It would remain so:

—In 1890, as we will see, the first attempt at mounting a national league playing baseball under the American code was made. Derby Industrialist Francis Ley imported battery mates John Reidenbach and Simeon Bullas/Bullis from Cleveland, Ohio; the pair proved so dominant that Ley had to agree to only play them together in games against the next-strongest team in the league, Aston Villa. It was a promise that Ley failed to keep, and the outrage of the opposing teams forced him to withdraw Derby from the league. The league folded that same year (albeit, admittedly, because of a lack of funding, not conflict between the teams).[20]

—In 1906, J.A. McWeeney, secretary of the newly formed British Baseball Association (BBA), reflecting on the failure of the 1890 league and the ire the above incident caused, promised in print that in the BBA, ‘No American, nor anyone who has learned his baseball in the States, will be allowed to pitch’.[21] That promise had already been broken by the time McWeeney made it, as William Jarman and Fairy Marsh, Englishmen who had learned their baseball in the Ohio National Guard and US Navy, respectively,[22] had already debuted as a battery for a scratch London team in a game against Oxford Rhodes Scholars and would go on to be a dominant force in the BBA. Within a couple of years, stung by criticism in the US press of games with mid-double-digit scores, the BBA would abandon even the pretence of keeping its promise and bring in American players. Scores went down, but so did spectator numbers. The BBA folded in 1911. The presence of Americans in the game was blamed for its failure in the British press.[23]

—The last and ‘arguably the most serious attempt’ to introduce American baseball into Britain before the modern era took place in the 1930s and was led by sports betting magnate John Moores—not coincidentally, a Liverpool man. The leagues started strong, backed by Moores’ considerable financial resources and organisational and marketing skills, but soon stumbled. The issue was once more spectator disinterest, driven largely by the lack of scoring and dominance of imported American and Canadian batteries.[24]

The conscious differences between the LRA rules and the rules of American baseball that they used as their model were designed to make their game appeal to the British familiarity and established appreciation of long periods of uninterupted play, high scores, and high run rates. The LRA even adopted a flat bat in place of the American ‘club’, allowing the range of strokes that British spectators enjoyed watching in cricket. They did not employ a foul line for the same reason—the batsman edging the ball in unexpected directions was legal and desired, to keep play interesting; again, subsequent events would show that this was viewed as a red line by the LRA. This is not to say that the LRA equivalent of the baseball battery (the ‘bowler’ and ‘backstop’) could not play a leading role in influencing the game—shut-outs, though incredibly rare, still happened[25]—it is just that, given the number of times a player was at bat, particularly when coupled with making it to first base putting a run on the board, simple probability meant that runs would in most circumstance be scored even in the face of an experienced battery. Empirical evidence to support this statement would be provided by events in 1889. However, before describing those, let us return to the development of rounders following the foundation of the LRA.

In his 1883 letters to the local press, LRA secretary W.H. Hivey reported that in Liverpool, there were 26 teams already in existence and 1000 players. He also announced the inauguration of a Challenge Cup competition open to all. (Jumping ahead: it would not be until 1890 that leagues would be set up, comprising senior and junior leagues, each featuring the best eight teams in each tier.[26]) By 1885, the number of clubs competing for the Challenge Cup had increased to 50, and the number of teams in the LRA to 80. That same year, a letter writer to the North British Daily Mail boasted that ‘rounders is the only game played in Liverpool during the summer months, while in Manchester, Birkenhead, Bootle, Widnes, &c., &c., it is highly popular’. He went on to describe a game in June of 1884 that attracted ‘between 5000 and 6000’ spectators. His principal reason for writing was to report the establishment of the first clubs in Scotland.[27]

This planting of the game in other parts of the country was the major feature of the final years of the 1880s. It did not thrive in Scotland, but it did take root in Gloucestershire (in 1888). This was almost certainly the small local rounders scene, kicked off by the City of Bristol Rounder Club in 1864, adopting the Liverpool rules. More significantly for future developments, it also took root in South Wales (in 1890), again, likely a case of the small local rounder scene active since 1870 adopting the Liverpool rules. By this time, the original LRA had, in light of its aspirations, renamed itself the National Rounders Association (NRA), creating a new subsidiary LRA to govern the sport in Liverpool.[28] Of equal significance to these events was the return in 1889 of the American baseballers.

Sir,—I noticed T. Bradshaw’s letter in your valuable paper last night about giving the American baseball team a good reception on their visit to Liverpool, which I hear will be about the middle of this month. The game of baseball is little different to rounders, so what is there to hinder a scratch team of rounders players being formed and a challenge being sent to the baseballers. […] LOVER OF ROUNDERS.[29]

The 1889 baseball tour of England was the brainchild of Albert Spalding, player and promoter of the 1874 Wright tour, now enjoying his self-appointed role as baseball’s chief booster, manufacturer of sports equipment, and publisher of sports books, including Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide.[30]

The games in Liverpool took place on Saturday 23 March 1889 at the Police Athletic Ground on Spiel Road, in front of a crowd of 6000–8000 (the largest of the tour). The two touring American teams, the Chicago White Stockings (owned by Spalding) and ‘All-America’, opened the action by playing a five-inning baseball game against each other that ended 2–2. Next, a scratch team of 11 Americans (including Spalding as pitcher, although at least one account lists Baldwin as the pitcher [31]) played a scratch team from the LRA at rounders. The LRA team scored 18 runs in its first innings. In reply, the American team made 8 runs in its first innings, forcing the follow-on, and made 6 runs in its second, giving the game to the LRA players by an inning and 2 runs. Finally, in a game of baseball, the LRA players failed to score across three innings, while the Americans scored 16 runs in their first innings and 1 in their second before the result was called due to rain.[32]

Although the performance by the LRA players in the game of baseball was described in the press as a ‘poor show’ and there is little doubt that the Americans were the more skilled players, there is equally little doubt that what the—admittedly partisan—crowd took away from this was the advantage that the American rules gave to the defending side and how this advantage was nullified by the rules under which rounders was played.

That the Americans did not deploy their best battery in the rounders game—Spalding himself serving as bowler—may go some way to explaining their failure to achieve the shut-out in the rounder game that they achieved in the baseball game (in which the pitcher was the Chicago White Stockings pitcher Baldwin). However, against this, the American view of the rounders game was that the Americans’ defeat was entirely due to their unfamiliarity with the rules, particularly as they batted first, and if a second game had been played, the Americans would have won. This supports the argument that the impact of the pitcher/bowler on the game was dulled by the rules of rounders: the Americans needed time to come up with a different approach. It is worth noting a further outcome of this encounter: baseball historian William Morgan, writing in 1981, points to the adoption by the NRA of two-handed batting and the harder junior baseball over the softer rounders ball at this time as being a result of the encounter between the rounders and baseball players in Liverpool in 1889.[33]

Regardless of the true level of impact of the American choice of pitcher/bowler on the result, the spectators, ignorant of the relative skills of the American players, would not have appreciated this. So, ultimately, all that Spalding achieved by agreeing to play the LRA at its own game and then deciding not to use his best pitcher was to convince the crowd of how much more to their taste the rules of rounders made the gameplay.

The 1889 tourists left without having put in place anything that might grow the game of American baseball in England. However, in the summer of 1889, Spalding Bros. arranged for players from Yale, Harvard, Dartmouth, and Princeton Universities to travel to the UK specifically to teach the game to local sportsmen—Andrew Brotchie’s spiritual descendents. This was an effort organised, at least from the UK end, by Newton Crane, former American consul in Manchester.[34] Distinct from the Spalding world tour approach, the collegians invited local sportsmen to play alongside them in mixed teams, offering instruction in the finer points of the game before the commencement of play. In doing so, they created a pool of players familiar with the American rules. They also provided a template for the UK-based baseball enthusiasts who sought to leverage the publicity of the Spalding tour to launch the first nationwide baseball league in Britain—an effort, once more, led by Newton Crane.

It has been urged against baseball that it is simply an improved form of rounders. It undoubtedly owes its origins to rounders, but it bears less resemblance to that game than modern cricket does to the ancient sport of the village-green, where an inverted milking stool and wooden balls were the rude implements of play. The modern game of baseball has been developed from its crude origin in rounders within the memory of those still able to play it.[35]

Robert Newton Crane (1848–1927), newspaperman, government envoy, baseball booster, and lawyer, was born in New Jersey in 1848, the son of a Wesleyan minister. His chief claim to fame during his lifetime was that he was the first American appointed to the role of King’s Counsel (KC)—the highest ‘rank’ of barrister in the English legal system. Perhaps to modern eyes, of greater significance was that he was a prominent eugenicist who advocated in print for the adoption of marriage laws aimed at ‘…preventing procreation by undesirable spouses’, invoking the spectre of what Theodore Roosevelt called “race suicide” to support the need for such measures.[36] However, it should be recognised that Crane and Roosevelt were far from being alone in holding such views; Crane, like Roosevelt, was a product of his times.

After a period working as a newspaperman in the US, Crane arrived in England in 1874—the same year as the Wright tour—and served as American consul in Manchester until moving to London in 1880 to practice as a lawyer. In October 1889, in the wake of the successful visit by the collegiate baseball players, Crane chaired a meeting in London that resulted in the formation of the National League of Baseball of Great Britain (NBL), with Crane as its provisional chairman. Its first order of business was establishing a list of locations throughout the country to which could be dispatched American experts hired to tutor local sportsmen in the rules of the game. Although most of these experts would be selected by Spalding Bros. through a recruiting campaign in the US newspapers, a few would be drawn from American students already in the UK, chief among them, medical students at Edinburgh University—a circumstance that I have explored elsewhere.[37]

The other attendees elected to the provisional council alongside Crane represented mostly a mix of association football and cricket interests—reflecting the mission of the new league to supplement the winter game (association football) and appeal to those sections of British society that the summer game (cricket) had been largely unable to reach (working men). The odd men out, and of particular interest to us here, were Derby industrialist Francis Ley, of whom more below, and W.H. Hivey, secretary and treasurer of the NRA. The presence of the latter makes plain that Crane intended to bring the rounders association ‘into the fold’. As we have seen, ultimately, the NRA would go its own way and form its own leagues the following summer. However, as discussed below, as late as the spring of 1892, the NRA was still discussing the possibility of merging with the new organisation if the sticking points could be overcome, but there are hints of what they might be as early as late 1889/early 1890, in the following passage in the baseball section of the 1890 edition of a British sports guide, The Boy’s Modern Playmate: While these pages are passing through the press, an endeavour is being made to introduce a Baseball that is not so complicated as the American game herein described, but the formal rules have not yet been decided on. The NRA wanted changes to the code. [38]

By the summer of 1890, the Baseball Association of Great Britain had been formed to govern the national professional league and amateur associations, a relationship designed to mirror that between the Football Association (FA) and its leagues. Its chairman was Rev. F. Marshall, chairman of the Yorkshire Rugby Union. Somewhat bizarrely, when asked his views on baseball shortly after his appointment, Marshall replied, ‘As a game I think it distinctly inferior to both football and cricket, and presenting little of the scientific features of the latter game.’[39]

This did not bode well. Similarly, despite its aspirations to be a national league, and despite tutors being successfully embedded in local sports scenes, most prominently in Middlesbrough in the North-East of England, where the amateur Cleveland & South Durham League was established, the four teams that made up the professional National Baseball League in its first—and only—year of operation were all from the Midlands: Aston Villa, Preston North End, Stoke, and Derby. Not coincidentally, this encompassed an area that was a heartland of Association Football, and the heartland of rounders, again, reflecting the aspirations of the game to become the summer sport for football players and fans; a position occupied at the time in Liverpool by rounders. A clash was inevitable.

WITHDRAWAL OF THE DERBY CLUB. In consequence of a letter received from Mr. Ley that a rupture had occurred in the National Baseball League and the Derby team were about to retire from the League, our representative saw Mr. Ley and got further particulars about the affair.[40]

I do not propose to detail the events of the 1890 national baseball league season here, as other authors have already done so with far more insight than I could provide.[41] Instead, I will focus on its dominant personality, not a player but an owner, Francis Ley (1846–1916). Ley was a Derby industrialist, the owner of an iron foundry, who had become interested in baseball during an 1888 tour of ironworks in America; on his return, he added a baseball section to his existing works recreation club. Upon becoming involved with the newly formed NBL, he set about creating a sports ground suitable for the playing of baseball. It was the best baseball ground in England, certainly in the 10 years that baseball was played there and possibly up to the present. In 1895, it also became home to Derby County Football Club, and, as the Baseball Ground, would be where Derby played their home games for the next 100 years.

As part of his efforts to introduce baseball to his workers, Ley had asked his business partners in America to send him some ironworkers who could work at his Vulcan works and teach their English colleagues the sport at the same time. The men his partners sent were the John Reidenbach and Simeon Bullas/Bullis mentioned above.

It was not just in the skills of its players that Ley’s Derby excelled, however, it was in Ley himself; his commitment to the success of the game was far greater than those of the owners of the other teams in the league, who were, rather, simply giving the new venture a go. Thus, when the league collapsed after only one year, although the other clubs continued as amateur affairs for another couple of years before collapsing for want of money, Ley not only kept the Derby club going, even though, as discussed above, he had withdrawn the club from the league over criticism of his use of his star battery—something that had led to Albert Spalding filing a lawsuit against him (Spalding later withdrew the suit and paid Ley’s costs[42]), he also continued to invest in keeping it the best baseball club in Great Britain. The club won three national championships across the ten years of its existence (1895, 1897, and 1899[43]).

This was the Derby baseball club that the NRA challenged to two games under the American rules in the Spring of 1892. To explain the background to the challenge being issued, we need first to look at how the NRA responded to the creation of the NBL—by forming a league of its own.

No one can deny, after the splendid exposition made by the Union on the last two Saturdays, that they are the finest combination extant. Last Saturday’s gate-money, taken at their match with Kensington, ought to be a solacium to the National Rounders Association for their unrequited efforts for some time past to replenish their exchequer.[44]

The logic of the NRA forming rounders leagues was that of the Football Association by way of the NBL: the best way to build fan numbers and fan loyalty was to offer supporters a chance to follow a team week-by-week as it progresses through a league rather than watching it stake everything on a single roll of the dice in a Challenge Cup. Not coincidentally, this was also the best way to retain player loyalty in the face of the lure of American dollars urging defection to the NBL. Thus, the same year the American code launched the NBL, the NRA launched two leagues in Liverpool (both its stronghold and the place at greatest risk of falling to the NBL), a senior league and a junior league, each with eight teams. The teams in the senior league during its first two years of operation (1890 and 1891) were Union, White Star, Kensington, Mossley, Keystone, Chesterfield, Waterloo, and Newnham.[45]

Given the defensive nature of this move, and given that the NBL collapsed within a year, it is with some irony that it can be reported that, within two years of their formation, the NRA leagues were experiencing some of the same problems as the NBL; specifically, the disparity in skills between the best-performing and worst-performing teams in the senior league was such that the worst-performing teams had so little chance of avoiding a heavy defeat in games against the best-performing teams that they and their fans fell into despair and lost the desire to continue playing. In its second year, the senior NRA league even had its own Derby and John Reidenbach in the form of the all-conquering Union team and its bowler John Lamont, who, in September 1891, achieved the incredibly rare feat of shutting out the batsmen of the second-best team in the league, the White Star, in one inning of a two-inning game. Needless to say, the rounders press, while praising Lamont for his achievement, were less than complementary about the quality of the spectacle it presented to the fans.[46]

There was a second reason that the NRA was struggling to retain the services of its best players: the image of the sport itself.

It ought, however, to be said that no one knowing anything of [Base Ball or Rounders] would presume to place the extremely simple Rounders on the same footing as the more inspiring and intricate Base Ball.[47]

By the time the National League of Baseball of Great Britain launched in the summer of 1890, the British press had become so used to calling the sport a form of advanced or scientific rounders that it had become almost a reflex action. The flipside of this was the solidifying perception that rounders, by extension, was simply a crude progenitor of a superior American offspring. Cassell’s Book of Sports and Pastimes, from which the above quote is taken, the bible of structured leisure, first published in the early 1880s, only reinforced this view. ‘Base Ball’ was included in the section on ‘Manly Games and Exercises‘, while rounders was relegated to the section on ‘Minor Out-Door Sports’. In early editions, the entry on rounders (page 225) allowed that in parts of the country it was played under ‘strict rules’, but went no further. Sometime before 1896, Hivey persuaded the editors to change this to read ‘The more elaborate [version of the] game, which is identical in all essentials to Base Ball, is governed by strict laws’ (emphasis as in the original) and add his contact details for further information. He could not, however, persuade them to remove the description of rounders quoted above, which was appended to the section on Base Ball. Whatever the NRA’s view of the game as they played it, to the British people at large, since the [re-]arrival of American baseball in the country in 1889, they were seen as adults playing at a child’s sport.

The great prejudice against it being its name—people when they heard that men were going to play a game of “Rounders” thought of the schoolboy game, and had no idea how that had been improved, and that it was now played on scientific principles.[48]

This perception was also blamed for the inability of the sport to grow beyond its established roots in Lancashire, Gloucestershire, and South Wales, something that weighed heavily on the minds of the members of the NRA council.

It is against this backdrop that in March 1892, W.H. Hivey attended a meeting in Manchester of the proponents of American baseball. The main order of business of the meeting was to reconstitute the former Baseball Association of Great Britain as the National Baseball Association (NBA) with Newton Crane as its president; however, also on the agenda was a proposed merger between the NRA and the new NBA.

MR HIVEY, of Liverpool, of the National Rounders Association, addressed the meeting on the proposed amalgamation of the Rounders Association and the Baseball Association. He said the question had been discussed in Liverpool, but they had not taken a vote on the matter.[49]

It is at this March 1892 meeting that Hivey presented the NRA’s red line—the three elements of the American code that, as far as the NRA was concerned, had to be removed for any merger to happen. It will come as no surprise that they were the elements that restricted high scores and variety in stroke play:

1. The way the ball was delivered.

2. The three-out-all-out system.

3. The restrictions placed on the batters by the foul line.

In response, Newton Crane offered a remarkable ‘one-association, two-code’ solution, where the NRA would become part of the NBA but continue to enjoy a high degree of autonomy, its teams continuing to play rounders against each other but baseball against other teams in the NBA. Leaving aside the obvious question of how long in practice this high degree of autonomy would last, it is a mystery how Crane expected this one-association, two-code system to function; for example, what would be the primary code of new teams joining the association—would they be allowed to choose for themselves?

What Crane had presented—and as subsequent events would show—was not a viable solution for a merged association; however, it was a workable format for a ‘two-association, two-code solution’: two associations whose teams and players, outside of their regular leagues and challenge cups under their own code, would be free to play teams from the other association under their code.

Hivey’s only response to this offer (at least, as recorded by the press) was to bullishly promise to form a baseball team from NRA players to be called the ‘National Rounders Baseball Club’ that would ‘guarantee to beat any baseball players if a fair notice of a match were given them’.[50] This is the challenge that led the NRA to field a team against Derby.

It is not clear if Newton Crane expected the NRA to vote for or against a merger, however, it is clear that he did not expect that, having voted against a merger, the NRA would adopt a different solution to the problem of the prejudice against the name ‘rounders’: change its name.

The National Rounders Association announced the change of name to the ‘English Baseball Association’ (EBA) in April 1892, just one month after the Manchester meeting; the Gloucestershire Rounders Association adopted the same name at the end of May, by which time, the South Wales Rounders Association had changed its name to the (rather convoluted) South Wales English Baseball Association (soon shortened to simply the South Wales Baseball Association).[51]

Newton Crane sharpened his pen.

To what we can be sure was Newton Crane’s satisfaction, the first game between Derby and Liverpool under American rules, which took place in Liverpool on Saturday, 25 June 1892—and which Crane himself umpired—resulted in a convincing win for Derby, 27–6. The return match at Derby played the following week was again a victory for Derby, but by a much narrower margin, 18–10, which was viewed by both the Liverpool and the Derby papers as a credible result for a team inexperienced in the rules of the game playing one tutored by an American professional.[52] Although the rounders baseball team did not live up to the boast made by Hivey at the Manchester meeting, the encounters did at least reinforce for the newly christened EBA the correctness of its decision to continue to go it alone.

If, however, the EBA thought this was the end of the matter, it was sadly mistaken. To understand what happened next, we need first to consider the position of the NBA at this moment in its history. To move the game of baseball forward in Britain, it needed everyone involved in baseball in Britain to be pulling in the same direction. While the Liverpool group was calling its game ‘rounders’, its existence outside of the NBA was of little import beyond the competition for players in the areas where rounders was strong. However, once the Liverpool group changed the name of its game to ‘baseball’, it became a matter of vital importance to the NBA that it was brought into the fold, if for no other reason than, as events would show, the press would get the two organisations confused,[53] diluting if not outright corrupting the NBA’s message. It is no surprise that Crane felt he had to act.

At the end of July 1892, the amateur teams that played as ‘Liverpool’ and ‘Manchester’ under the American code played each other in a tie in the NBA’s English Challenge Cup. In its report on the 1892 season under the American code presented a few weeks later, the NBA stated that four Liverpool EBA teams would be taking part on the Cup the following season.[54] The language suggested this would be a permanent switch of codes—a victory for the NBA; in fact, it was the workable version of the Crane two-code system (two associations, two codes, not one association, two codes) proving itself: EBA teams, one of whom was the associations’ strongest team, the Union, trying its chances in the NBA Challenge Cup under the American code while continuing to participate separately in the EBA league and Challenge Cup competitions under the English code.[55]

This event should have represented the inauguration of a workable compromise that both associations could get behind, a stable two-association, two-code system, with players moving between the two codes, and teams from one code on occasion playing games under the other code. Instead, in the Spring of 1893, the NBA renewed its assault on the EBA by mounting a lightning campaign to persuade the South Wales Baseball Association to make a permanent switch from the English to the American code.

Rounders is played in two cities out of Wales and is going back every year. Baseball is played in almost every town in the North of England and Midlands Counties, and is going forward ten times faster than any other field sport ever did.[56]

The 1893 NBA South Wales campaign was led by J.F. Appleton, a member of the NBA council and leading light of the American baseball scene in first Lancashire and then the North-East of England, here recast as the secretary of the National Baseball Association of South Wales.[57] The campaign had several fronts: arranging for an exhibition game to be played between an Appleton-led team and a local SWBA team (Grangetown) under the American code; stump speeches by Appleton to local bigwigs extolling the virtues of American baseball; and the co-opting of the ‘Local Sport’ column of the Western Mail to push the NBA narrative—a deal sealed by a personal letter from Newton Crane to the column’s editor. How can the rounders crowd call their game ‘baseball’ when a sport by that name already exists? Asked one supposedly neutral correspondent. I have played and enjoyed both rounders and baseball, swore another, and that has shown me the superiority of the latter as a senior game; rounders is best left to the juniors. Appleton also contributed, in the form of, as the quote above shows, an appeal to reason—couldn’t the rounders crowd see that their game was dying? They should surrender to the inevitable and join the winning side.[58]

All of this was directed towards the prospective attendees of a meeting organised by the SWBA to discuss whether to stick to the English code or switch to the American one (the calling of this meeting may also have been part of the NBA campaign). In its 10 April announcement of the meeting, the SWBA laid out what we can now recognise as Appleton’s case: The change in name from rounders to baseball was done in the belief that it was the name only that was holding the game back; however, the game still had not grown beyond its heartlands. The only way for the SWBA to grow was to recognise that it was the game itself, as the SWBA and EBA played it, that was the problem, and so, switch to the American code.[59]

The meeting took place in Newport on 2 May 1893, and Appleton was present to argue the NBA’s case. However, the result was defeat; the SWBA opted to continue to play under the English Baseball Association code[60]—their view was no different to that of the erstwhile NRA in March of the previous year: they had their red line when it came to adopting elements of the American code that, in their view, broke up play, restricted scoring, and limited the variety of strokes available to the batter.

For its part, the NBA viewed this rejection as the ultimate in truculent nativism, rejecting a lifeline simply because it had a foreign source. Appleton returned to the North-East of England, and the NBA set about coming up with a new approach. This exercise culminated, in 1894, in the NBA gathering together its supporters in North-West England to propose the establishment of the Liverpool and District Baseball Association.

This was the mess that Lincoln Sterne was getting himself into.

The Liverpool meeting was an even greater success than was anticipated. A large attendance gratified the promoters, and among those who were present were Mr. George Mahon, the well-known and capable president of the famous Everton Football Club, who occupied the chair, while Mr J. Houlding, president of the Liverpool Football Club, was represented by his manager, Mr. Houlding being out of town. Dr Sterne, an enthusiast and skillful player, was present from Manchester. A decision was made to form an association, the Liverpool and District Baseball Association.[61]

This is not the place to go over the well-trodden ground of the 1892 dispute between Everton FC board members, led by George Mahon, and their president, John Houlding, that led to Houlding leaving the club and founding Liverpool FC. It is, however, interesting to note that by no later than 1895, both the Anfield football ground, owned by Houlding and at the heart of the dispute, and Goodison Park, Everton FC’s new home, were hosting games of baseball. Specifically, that year, EBA Globe Cup games were played at both grounds, culminating in Everton FC offering the use of Goodison Park free of charge for the final, which was between the Union and Everton Baseball Club (not affiliated with the football club). That game took place on 31 August 1895 and was won by the Union 67–48 (see scorecard at the end of this article).[62] (As an aside: the ‘Globe Cup’ was the EBA’s own World Series, which is to say, it was named after its sponsor, The Globe Furnishing Company.[63])

This, coupled with the fact that one year earlier, both Mahon and Houlding were willing to put their names to the effort to expand the NBA presence in Liverpool, speaks to the degree that Association Football clubs still saw baseball—under either code—as a summer sport to complement the winter game. As we will see below, this included allowing their players to play baseball in the off-season. However, the most remarkable thing about the July 1894 meeting and its outcome is that, other than Lincoln Sterne, a dyed-in-the-wool Yankee baseball player, the team that emerged from it, intended to contest itself against, of course, Derby, was made up entirely of stalwarts of the EBA.

Derby Baseball Club being anxious to meet a nine of Liverpool, the following were selected as representatives, subject, of course, to the players’ approval:–W M'Gaw (pitcher), R Burrows (catcher), J Coke (No. 1), J Ingoldsby (No. 2), T Williams (short stop), DE Connor (third base), CH Gill (long field), W Smith (centre field), and Dr Sterne (right field). Reserves: J Ryder and J Fitzsimmons. As several gentlemen of influence have promised the undertaking their support, success seems almost assured.[64]

McGaw, Burrows, and Ingoldsby were Everton players. Coke was the captain of the Union—one of the EBA teams, it must be remembered, that had participated in the NBA Challenge Cup the year before. Connor, who would become secretary of the Liverpool and District Baseball Association, was another Union player, as were Gill and Smith. Williams played for Seafield. Five of the men— McGaw, Burrows, Connor, Coke, and Gill—were veterans of the 1892 Liverpool EBA games against Derby under American rules.[65]

It must be emphasised that all of these players would continue to play for their respective sides in the EBA, even Connor, despite the latter enjoying an official capacity in the NBA as secretary of the American Baseball Association in the city.

To me, the meaning of this is clear: the NBA, as its actions the previous year in South Wales show, was intent on replacing the game that the EBA played, which the NBA refused to call ‘baseball’, with the ‘genuine’ article. The EBA, clearly recognising that it could never accomplish the reverse, was instead content to let its players and teams move backwards and forwards between the two codes—again, in something akin to the workable version of the Crane two-code solution. On a national scale, the EBA’s position was clearly the weaker of the two, as its reluctance to insist on its players and teams playing only by the English code shows: it was scared that its players would defect permanently to the NBA. However, at a local level, the NBA, by simply offering EBA players an opportunity to play games under the American code as opportunities arose, while otherwise continuing to play their regular games under English rules, was admitting its own lack of support in the Liverpool area.

This was a ‘two-association, two-code’ solution applied on a micro-level. Of course, we can speculate that Newton Crane was hoping that, in time, the EBA players would opt to play more and more of their games under the NBA code, causing the EBA to wither and die; but for that to happen, the NBA would have to furnish the EBA players with enough opportunities to do so. As we will see, they could not do that. So, in Liverpool, at least, the two codes had to learn to live with one another.

Unfortunately, nothing seems to have come of the proposal for a game against Derby. Instead, local players, again, mostly from the EBA, met for a practice match under the American code in late July. Lincoln Sterne was not present for this game, but there was one significant attendee from outside the EBA’s ranks: William ‘Billy’ Stewart, wing half for Everton FC (recorded in a press account of the game as ‘W. Stewart (Everton FC)’).[66]

Some of the players of the Everton and Liverpool football clubs are anxious that baseball nines should be established in Liverpool, which they would enthusiastically support.[67]

The presence of footballers in the line-up of clubs under the American code was a feature of the 1890 NBL, and designedly so, in keeping with the idea of the sport being the summer complement to Association Football. It is thought that the ‘Stewart’ who played for Preston North End Baseball Club in the 1890 NBL is the same Billy Stewart, who was on the books of Preston North End Football Club at the time. I do not know how strong an attribution this is;[68] however, the recorded presence of Billy Stewart playing American baseball in Liverpool while on the Everton FC books is strong support for it. To this may be added the fact that early in August 1894, it was suggested that a game be got up between the Liverpool American baseball enthusiasts and the current Preston North End team.[69] However, the same report noted that the new football season was only 3 weeks away, so the baseball season would soon be ending. In the event, again, it seems nothing came of that proposal for that reason.

Great disappointment is evinced by those interested in the American game that Liverpool baseballers are unable to place a team in the field to oppose the Boston amateur champions, who arrive in Liverpool about the 20th inst. A meeting was called by Mr D.E. Connor, secretary of the Liverpool (American) Baseball Association, to consider the matter, when it was deemed inadvisable, owing to the shortness of time for practice and advertising, to entertain the challenge.[70]

The failure of Liverpool’s American baseball enthusiasts to put together a team (from EBA players) to play against the touring ‘Boston Amateurs Club’ (of dubious origin[71]) in the late summer of 1895 was again indicative of the problems that the NBA had in trying to provide players in the city with opportunities to play under the American code. Liverpool was too far from the centres of the American game in England (by this time, the North-East of England and London) for the NBA to provide teams for them to play against. This was itself a sign of the malaise that had fallen upon the NBA due to its failure to grow the game beyond its early adopters—a topic beyond the scope of this article.

When the ship carrying the American team docked in Liverpool in late August 1895, D.E. Connor, who pulled double duties as EBA star player and standard-bearer of the American code in the city, was reduced to simply acting as the American teams’s guide in getting from the port to the railway station for the train that would take it to Derby for its first game.[72]

Eighteen Ninety Five was also the year that Newton Crane stepped down as president of the NBA; the role passed to Francis Ley.[73] However, the organisation would have little relevance beyond running the Challenge Cup going forward and would cease to be active by 1901.[74] Crane would, however, continue to be an advocate for the sport in England and lend his name to organisations attempting to revive the game up until the 1920s.[75] He died in London in 1927.

William H. Hivey, the guiding light of the NRA/EBA and Crane’s nemesis, stepped down as EBA secretary in 1894.[76] Although, as we have seen, the EBA arguably still had its best years ahead of it at this point, without his force of personality, the EBA too lost its way towards the end of the Nineteenth Century. There was even a brief period at the dawn of the new century when it could not put together enough teams to run a senior league. However, after a brief interregnum, the sport in Liverpool would revive at least to the point that it could sustain league and cup competitions locally until interrupted by the First World War and then pick up where it had left off at the war’s end. From 1905 onwards, it was even able to organise ‘Baseball Internationals’ in the form of games between the pick of the EBA and the renamed Welsh Baseball Union playing as ‘England’ and ‘Wales’, respectively.[77]

Hivey died in 1950, aged 98,[78] and so lived to see the revival in the early 1930s of the American code in the city under the auspices of Liverpool sports betting magnate John Moores. The first step in, at least for a time, a successful attempt to revive the sport at a national level,[79] Moores’ strategy for interesting local sports fans in the game was the pit local teams against visiting teams drawn from American medical students at Edinburgh University (games that he cheekily called ‘Baseball Internationals’,[80] in a direct steal from the EBA) and the crews of Japanese merchant ships docked in the city.[81] His source of local players? Players from the EBA. In fact, Moores had first become involved with the sport of baseball when, in 1932, he became the patron of the breakaway English Baseball Union (EBU), which split from the EBA but continued to play under the English code, featuring as it did some of the EBA’s star teams, including Everton. In early 1933, Moores travelled to America and saw baseball played under the American code for the first time, and returned to Liverpool convinced this was the way ahead. Alas for Moores, neither the EBA nor the bulk of the EBU saw things that way. However, a few teams and some players did make the switch. The most famous player to make a permanent switch was Everton footballing legend, Dixie Dean, who, in the 1920s, played for EBA team Blundellsands, and then, in the late 1930s, turned out for a Moores American baseball league team, Liverpool Caledonians.[82] Two associations, two codes.

But what of Lincoln Sterne? In truth, beyond putting himself forward to play for the nascent Liverpool team in 1894, he appears to have had little to do with the stuttering efforts to grow the American game in Liverpool. However, he did not give up on the game, and within a few years, he was to become involved in one of the most remarkable combinations in English baseball in either code and any century: James Hardie’s Regent Theatre team.

BASEBALL: THE GAME IN MANCHESTER. Quite recently the Regent team, in which there are both North American Indians and American negroes, played a match with the members of the “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” Company, and they won decisively by 15 to 7. It is expected that very soon the team will journey to London to play a series of games with the best clubs in the metropolis. The composition of the present team is as follows:—Messrs E. Hardie (catcher), J Tate (short stop). J. Bigueo (second base), Liggins (left field), Cheeks (pitcher), J. M. Hardie (centre field), Seany Doctor (first base), Dr. Stern (third base), and Cropp (right field), with Benny Mercer as extra.[83]

I have written extensively about the Regent Theatre team and its opponents, the ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ Company elsewhere,[84] including positively identifying almost all of the players named in the report quoted above—the work that led to this article—however, in looking at how a medical man came to be involved in a multi-ethnic baseball team formed otherwise of variety artists, we need only consider Lincoln Sterne’s presence at that meeting in Liverpool in July of 1984, his love of sport, and the ease with which he mixed with all strata of society.

As later events would show, Sterne was a socialist who would at some point become a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP),[85] a political party that came into being precisely because of the failure of the Liberal Party to agree to field candidates with a working-class background. He was also a prominent member of Manchester’s large (for England) German community, which numbered around 1500 people at the beginning of the Twentieth Century and owed its origins to the city’s connection to the textile trade.[86]

The community was known for its liberal non-conformist views and made a particular strong contribution to the intellectual and cultural life of Manchester—the kindergarten movement entered the UK through Manchester; the Halle Orchestra, although not of German foundation, thrived on a repertoire of German music suited to the tastes of the bourgeois Germans in its audience; and Owens College, forerunner of the University of Manchester, had several German-born professors on its staff and benefited greatly from donations by Carl Beyer, the Anglo-German locomotive engineer who was a co-founder of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.[87]

Alas, despite all these contributions, the community would not survive the turmoil unleashed on the world by the outbreak of the First World War.

AN AMERICAN’S DISCLAIMER. To the Editor of the “Manchester Courier”. Sir:—Since the beginning of the war, I have suffered both unpleasantness and annoyance owing to the apparently widely circulated report that I was German. I took no steps to contradict the report till I found out that it was doing me harm both privately and professionally. I am a born American and registered as such at the American consulate here in Manchester; my father and grandfather were both Americans. Let me conclude with the seeming irrelevant statement that my only son is at present serving in the British Army.—Yours, etc., LINCOLN STERNE, D.D.S.[88]

Lincoln Sterne wrote his letter disowning any German identity within a month of anti-German riots breaking out across South London and just days after similar disturbances much closer to home, in Crewe. By December of 1914, there had also been outbreaks of rioting in Sunderland (following the bombardment of the Hartlepools by the Imperial German Navy) and parts of Scotland.[89] In May of the following year, it was Manchester’s turn.

BONFIRE OF FURNITURE. A house in Grey-street, occupied by a German and his English wife, was also visited. It is a small cottage in an entirely working-class district. The rioters damaged all the windows, and before the arrival of the police, a number of young men entered the house and completely ransacked the kitchen. The furniture was brought into the street, and in a few minutes, there was a huge bonfire. The residents sought refuge at the police station.[90]

The riots in Manchester followed the sinking of the Lusitania (7 May 1915). Although rioters arrested at the scene received punishment, the most far-reaching consequence of the riots was the arrest of over 160 German-born Manchester men as enemy aliens; the men were sent to Stobs Internment Camp in the Scottish Borders.[91] In a tragic sequel to the disturbances, George Schneider, a 25-year-old pork butcher whose shop had been wrecked by the rioters, took his own life after falling into a depression over the loss of his livelihood.[92]

The double blow of the riots and the internments shook the German community to the core, and although its members continued to live in the city for the rest of the war, it ceased to be a cohesive body from that moment. At war’s end, those people who still held tightly to their German identity returned to Germany; those with stronger ties to England became anglicised.[93]

For the moment, Lincoln Sterne remained in Manchester; however, he and his family, which by this time comprised his wife, Julia, a son, Edward, and three daughters, Dorothy, Marjorie, and Irene, began to spend more and more time in the United States and Canada. Edward emigrated to Canada in 1919 (in circumstances that did him no credit[94]) and then to the USA in 1923. Dorothy emigrated to the United States in 1920. A year later, Julia and Irene began to divide their time between New York and Manchester, making a permanent move by 1930. They would be joined by Marjorie in 1938.[95]

In the Spring of 1934, Lincoln Sterne visited Germany for what would be the final time. The year before, Hitler had been appointed Reichskanzler and begun ruling by dictat; we can only guess at what Sterne made of the country one year into Nazi rule; what is certain is that, the following year, he left England and Europe forever and returned to the United States. He died in New York in 1942.[96]

Shortly after the end of the First World War, Sterne was asked to present a talk at the Manchester Central branch of the ILP. Reflecting on the events that he had witnessed and the treatment that he had experienced, he chose to speak on the subject of ‘Intolerance’.

Jamie Barras, May 2025

Acknowledgments: Thanks are due to Gabriel Fidler of the Project COBB website and the British Baseball Hall of Fame for suggesting that Abraham Lincoln Sterne may be a subject worthy of further research.

Back to Diamond Lives

Notes

[1] Advertisements and Notices, Labour Leader, 27 November 1919.

[2] The information on Abraham Lincoln Sterne’s early life and parentage can be found in census returns: entry for Abraham Lincoln Sterne, NYC, 1870 US Federal Census; entry for Abraham L Sterne, NYC, 1880 US Federal Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 17 May 2025. His date of birth is given in various passport applications, for example, Abraham Lincoln Sterne, passport application, US Legation in Berlin, 19 May 1891,also ancestry.co.uk. The question of whether Sterne had any right to the title ‘Doctor of Dental Surgery’ (D.D.S.) is a vexed one, as he did not register with the UK Dental Council until the 1921 Dental Act made it a legal requirement, and the entry in the register does not record his qualifications—as someone who had practised dentistry for more than a decade, he did not need to provide qualifications. Entry for Lincoln Sterne, 1930 UK Dental Register, UK, Dentist Registers, 1879-1942, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc Operations, accessed 17 May 2025.

[3] See Note 2 above, final reference, for trip to Germany and Russia in 1891. That this was at least his second trip to Germany can be established from passenger records for NY arrivals, 1889, New York, entry for ‘Aug’ Lincoln Sterne, Passenger Lists, 1820-1920, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 17 May 2025. See also Note 5 below.

[4] Marriage of A Lincoln Stern and Julie Reunert: ‘Births, Marriages, Deaths’, Daily News, 21 September 1992. The marriage took place at St George Hannover Square, Mayfair, London, on 17 September 1892: entry for Julia Minna Reunert, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/, accessed 16 May 2025.

[5] ‘Great Swimming’, Buffalo News, 24 August 1887. Sterne is one of the competitors in the 100-yard race and described as being a member of ‘Neptune Swimming Club, Berlin, Germany’; Neptune (Schwimm-Club Neptun Berlin) was the original name of the Berliner Schwimm-Verein von 1878 e.V. (BSV 78). The name change happened in 1883, making Sterne’s use of the old name 4 years later interesting but this may simply have been because the old name sounded more . . . American.

[6] Newton Crane, President of the National Baseball Association, letter to the Liverpool Mercury, 23 June 1892.

[7] For the history of specifically baseball played under American rules in England in the final quarter of the 19th century, I have drawn extensively on Joe Gray, ‘What About the Villa?’ and ‘Nine Aces and a Joker’, Fineleaf Editions, 2010 and 2012, respectively. These and further works that at least touch on this early period are listed at: https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/research.html, accessed 19 January 2025. The Gray books can be downloaded from the latter website. For specifically, Spalding’s commercial interest in American baseball in England see, for example, Gray, What About the Villa?’, 142.

[8i] Newton Crane, ‘Baseball’ (London, UK: George Bell & Sons, 1891), 13, quoted in Gray, ‘What About the Villa?’, 11, Note 7 above.

[8ii] ‘Local and District News: Dingwall’, Saturday Inverness Advertiser, 7 May 1870; ‘Local and District News: Dingwall–Baseball’, Saturday Inverness Advertiser, 22 April 1871. Andrew Keith Brotchie can be identified as the ‘A.K. Brotchie’ in these articles from the report of his sister Euphemia’s wedding in 1868; this is also the source of Boston as the location for the family’s stay in the US: ‘Marriages’, Inverness Courier, 30 January 1868. From there, Andrew Brotchie can be traced on his return to the US in 1871 from US census returns for Weston, Massachusetts, e.g, entry for Andrew K. Brotchie, 1900 US Federal Census; year of his death: Massachusetts, U.S., Death Index, 1901-1980, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 3 January 2026. This information first came to light in 2013 thanks to research by Bruce Allardice for the Protoball Project. https://protoball.org/In_Dingwall_in_1870, https://baseballgb.co.uk/?p=16856, accessed 5 January 2026.

[8iii] Daniel C. Beaver, “Baseball, Modernity, and Science Discourse in British Popular Culture, 1871–1883.” The Historical Journal, 2022, 65, no. 5, 1310–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X21000704.

[9] W.H. Hivey, Hon. Sec. Rounders’ Association, letter to the Manchester Courier, 6 June 1883. W.H. Hivey was a Liverpool businessman whose firm sold mats, bags, and dunnage (package material); see, for example, advert, Sporting Gazette, 13 August 1887.

[10] David Block, ‘Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search For The Roots Of The Game’. (University of Nebraska Press: Bison Books, 2005).

[11] See, for example, ‘Base-ball […] is a sort of improved form of rounders’, ‘Base-Ball’, The Queen, 26 May 1888; ‘Scientific Rounders has been decidedly the sensation of the week’: ‘English Cricket versus American Baseball,’ Shepton Mallet Journal, 22 March 1889. For a comprehensive study of English reactions to these tours, see Daniel Bloyce, ‘That’s Your Way of Playing Rounders, Isn’t It? The Response of the English Press to American Baseball Tours to England 1874— 1924’, Sporting Traditions, 2005, 22, 81–98.

[12i] Founding of The City of Bristol Rounder Club: ‘Rounders v. Cricket’, Bristol Daily Post, 4 August 1864. City of Bristol Rounder and Cricket Club: ‘Public Notices—City of Bristol Rounder and Cricket Club’, Western Daily Press, 29 May 1868. Game with one inning of six-a-side and one of eight-a-side: ‘Rounders’, Western Daily Press, 24 August 1867. Six-a-side rounders match: ‘Rounder Match’, Bristol Times and Mirror, 6 September 1869. Rounders in Bristol district, 1877, ‘Drummond Rounder and Cricket Club’, Western Daily Press, 12 April 1877.

[12ii] ‘Rounder Match’, Cardiff Post, 23 April 1870.

[12iii] History of the Liverpool Rounders Club up to the end of 1877: ‘Liverpool Rounders Club’, Liverpool Mercury, 4 December 1877; scorecard: ‘Rounders’, Athletic News, 28 April 1877. This ‘Duke of Edinburgh’ is Prince Alfred, the second son of Queen Victoria. William Morgan: https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/bbhof/index.html, accessed 17 July 2025. Project COBB has an almost complete collection of Baseball Mercury available to download. Of particular relevance to us here is: William Morgan, ‘English Baseball Association’, Baseball Mercury, Issue 40, November 1985, https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/mercury.html, accessed 16 July 2025.

[13] There is a reference to a ‘Liverpool Rounders Association’ in a newspaper report in 1882. However, it should be noted that the association did not present itself to the outside world as a governing body of this new sport until the following year. Liverpool Mercury, 10 February 1882.

[14] See Note 9 above.

[15] D. Scur, Hon. Sec. Duke of Edinburgh Rounder and Quoit Club, letter to the Liverpool Daily Post, 8 June 1875.

[16] The differences between ‘British/Welsh Baseball’—the successor sport to the Liverpool Rounders Association—and American Baseball are explained succinctly here: https://www.rbiwales.com/british-welsh-baseball-vs-north-american-baseball-softball, accessed 18 May 2025.

[17] I acknowledge here that I am playing fast and loose with terminology in order to retain the sense of the comparison: in what is now known as ‘British/Welsh Baseball’, ‘bases’ are known as ‘posts’ as there is a physical post on the field, ‘pitchers’ are known as ‘bowlers’, etc. See Note 16 above.

[18] See Note 12 above, second reference.

[19] ‘The American Game of Baseball’, Evening Star, reproduced in the Lancaster Gazette, 29 August 1874.

[20] The best description of this episode is to be found in Gray, ‘Nine Aces and a Joker’: John Reidenbach, 5–16, see Note 7 above, second reference. Bullas/Bullis reflects the differences in the spelling of Sim Bullas’ surname in the press and in the official records; for the latter, see the entries for Sam Bullis and Elizabeth Bullis and family, in the 1870 and 1900 US Federal Censuses, respectively, ancestry.co.uk,Ancestry.com Inc., accessed 31 March 2025. The direct cause of the league folding was the withdrawal of financial support from Spalding; however, this simply demonstrated that it had not attracted enough support to become self-supporting. See Gray, ‘What About the Villa’, 158, Note 7, first reference, above.

[21] J.A. McWeeney ‘Baseball from an English Point of View’, 1906 special English edition of Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, ed. Henry Chadwick (London: British Sports Publishing Company, 1906), 58.

[22] Andrew Taylor of the Folkestone Baseball Chronicle Facebook page has researched extensively the careers of William Jarman and Fairy Marsh. This research led to Jarman being inducted into the British Baseball Hall of Fame in 2024. Marsh will no doubt follow his battery mate into the BBHoF in due course. He acquired the nickname ‘Fairy’ because of his fair hair. https://www.facebook.com/FolkestoneBaseball/, accessed 18 May 2025.

[23] Daniel Bloyce, ‘A Very Peculiar Practice: The London Baseball League, 1906-1911.’ NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, 2006, 14, 118–128.

[24] Daniel Bloyce, ‘John Moores and the ‘Professional’ Baseball Leagues in 1930s England’, Sport in History, 2007, 27, 64-87.

[25] Union bowler J.L. Lamont dismissed the entire White Star batting order for 0 runs in one of innings of a two-inning game in Liverpool in September 1891: ‘Rounder Notes’, Liverpool Evening Express, 5 September 1891.

[26] ‘Rounders Notes’, Liverpool Echo, 12 April 1890. For a representative set of league tables, see, for example, ‘Rounders Notes’, Liverpool Echo, 23 May 1891.

[27] ‘Rounders’, North British Daily Mail, 31 March 1885.

[28] ‘Gloucestershire Rounders Association’, Gloucester Citizen, 17 May 1888; the early history of the South Wales Rounders Association is described in: ‘South Wales Rounders Association’, South Wales Echo, 5 May 1892. The first mention of the National Rounders Association is made in 1886: ‘Athletic Notes’, Athletic News, 20 April 1886.

[29] ‘Rounders and Baseball’, Liverpool Mercury, 1 March 1889.

[30] See Gray ‘What About the Villa’, 12, Note 7 above, first reference.

[31] The players involved in the game of rounders are listed here: ‘Rounders and Baseball at Liverpool’, Cricket and Football Field, 23 March 1889. Baldwin is named as the pitcher in: Harry Clay Palmer, J.A. Fynes, Frank Richter, W.I. Harris. Introduction by Henry Chadwick, ‘Athletic sports in America, England and Australia. Also including the famous "Around the world" tour of American baseball teams’, (Philadelphia, Boston: Hubbard Brothers, 1889), 427—428.

[32] Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 30 March 1889.

[33] For US view of game, see Note 31 above, last reference and: ‘Baseball’, New York Herald Bureau, published in the Toronto Daily Mail, 25 March 1889. Rounders adopting US baseball practices: William Morgan, ‘The E.B.A. Game’, Baseball Mercury, Issue 27, May 1981, https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/misc/mercury/issue_27.pdf, accessed 14 July 2025.

[34] Crane is described as the ‘director’ of the collegians here: ‘Proposed Baseball League in England’, Birmingham Daily Gazette, 30 August 1889. ‘Harvard, Princeton, and Yale’: ‘Baseball Players in London’, Sporting Life, 2 September 1889. ‘Dartmouth’ and list of participants: ‘Baseball’, Western Daily Press, 17 July 1889.

[35] Note 6 above, 2.

[36] Crane’s biographical details: ‘Robert Newton Crane is Dead in London’, Ashbury Park Press (Ashbury Park, NJ), 6 May 1927. As a eugenicist: Robert Newton Crane, ‘Marriage Laws and Statutory Experiments in Eugenics in the United States’ (London: Eugenics Education Society (Great Britain), 1910); the quotes are from pages 3 and 7. Tract available to download at: https://archive.org/details/marriagelawsstat00cranrich, accessed 19 May 2025. Crane was a member of the Council of the Eugenics Education Society, which, in 1926, became the Eugenics Society.

[37] https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-washington-makes-his-bow, accessed 19 May 2025.

[38] The list of attendees and their affiliations was widely published; see, for example, ‘A Baseball Association’, Derby Daily Telegraph, 10 October 1889. Quote from Boy’s Modern Playmate: Rev. J.G. Wood, The Boy’s Modern Playmate (London: Frederick Warne and Company, 1890), 56. It is worth noting that this text would remain unchanged in subsequent editions. See, for example, the 1891 edition at archive.org: https://archive.org/details/boysmodernplayma00wood/page/n7/mode/2up, accessed 31 May 2025. It is also worth noting that the game under discussion may have been what was termed ‘Baseball-Rounders’, a hybrid game proposed in 1889 by ‘Old Rugbeian’ C C Mott as a sport ‘for boys’ (i.e., a sport for older children intermediate between rounders and baseball): ‘Baseball-Rounders’, The Field, 28 December 1889.

[39] ‘The Rev. F. Marshall on Baseball’, quoting an interview in the Umpire, Batley Reporter and Guardian, 19 July 1890.

[40] ‘Baseball: Withdrawal of the Derby Club’, Derby Mercury, 6 August 1890.

[41] See Note 7 above.