Iron and Ash

Jamie Barras

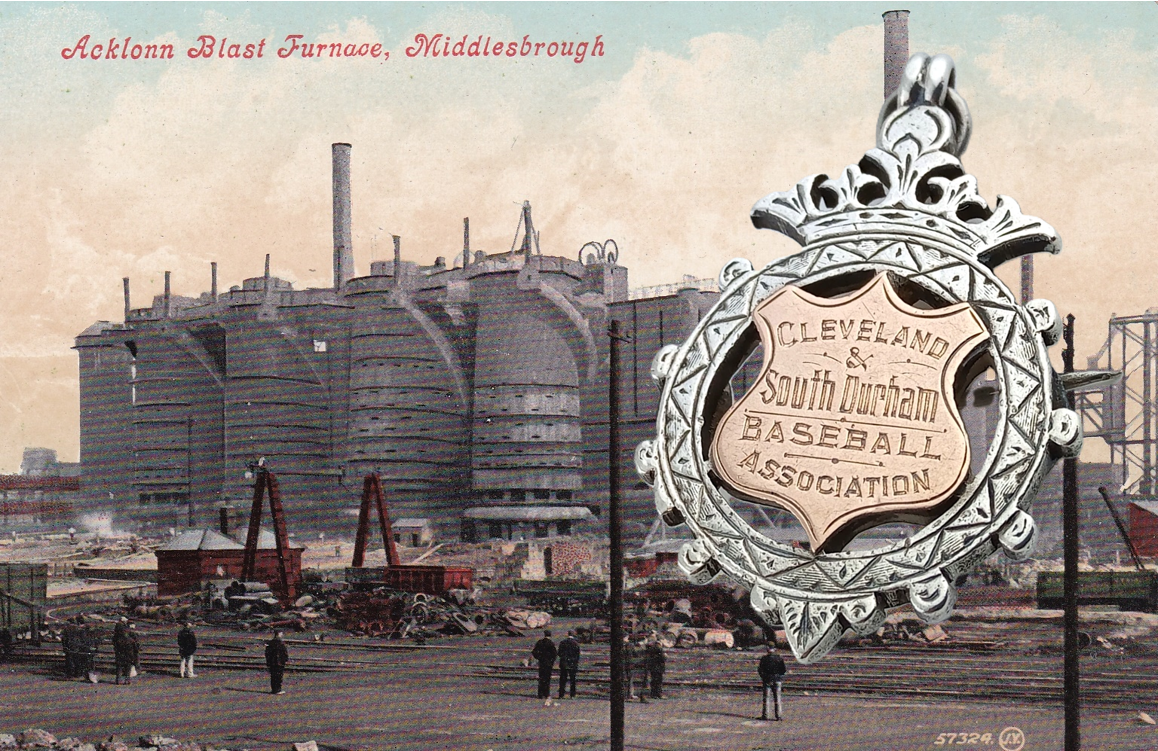

The boom in baseball in late-Victorian Middlesbrough lasted arguably only seven years (1890–1897); however, it represents perhaps the best example of how Victorian industrialists, imbued with the ideals of Muscular Christianity, embraced American baseball as a recreational activity that could improve the health and physical fitness of their workforce. The story of the scene has already been told, most notably by Catherine Budd;[1] my aim here is to add to these accounts by looking at the scene from the context of the relationship between baseball in Britain and the world of work. As such, this serves as a companion piece to my ‘Health, Recreation, and Baseball’ series.[2]

Col. Sadler returned from America with a profound admiration of baseball; and I am not surprised to see that a meeting has been called for Tuesday night to consider the advisability of forming a baseball club for Middlesbrough.[3]

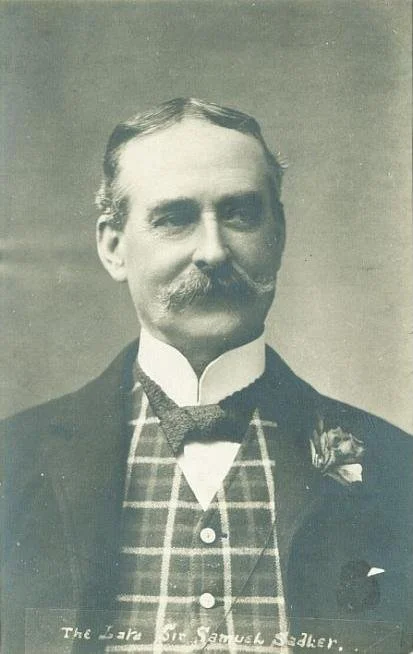

‘Col. Sadler’ was Middlesbrough industrialist Samuel Alexander Sadler (1842–1911). The ‘Colonel’ title was an honorary one, a reference to his 30-year association with the Volunteer Force of part-time soldiers, the Victorian forerunner to the Territorial Army. Sadler’s journey to becoming an ambassador for American baseball was a familiar one; like foundry-owner Francis Ley, 140 miles to the South in Derby, Sadler, the owner of a chemical company, had fallen in love with the game while on a business trip to the US, recognising in it a perfect form of physical recreation for Britain’s industrial workforce.[4]

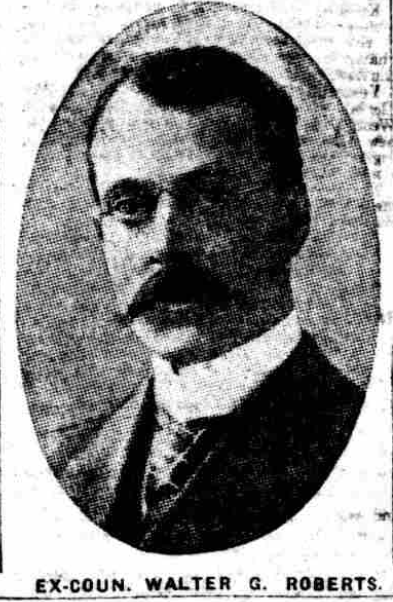

Arguably, however, the most important figure in Middlesbrough’s nascent baseball scene was Sadler’s partner in the effort, the wonderfully named Walter Garibaldi Roberts (1862–1939), who became not only organising secretary of the sport at the local level but also, in time, the organising secretary and later treasurer of the sport at a national level.[5] In many ways, Sadler and Roberts were cut from the same cloth: both Conservative with a capital ‘C’, both town councillors who rose to become town mayor, and both Justices of the Peace. They were also both believers in the ‘Muscular Christian’ ideal, which placed health and recreation at the heart of living a spiritual life—Sadler was involved with 17 different sports clubs and associations, while Roberts was president of the local YMCA. However, while Sadler was an industrialist, Roberts was an architect and, in keeping with his namesake, of a famously progressive and independent bent, a man who was described as being unafraid of being in a minority of one.[6] Perhaps the most striking example of Roberts’ willingness to follow his own path is the fact that, in 1910, he gave up his career as an architect to move to rural Suffolk for the sake of the health of his wife, Frances Hannah Roberts née Freestone (1863–1937). The pair took up farming and enjoyed another 27 years together.[7]

BASEBALL IN ENGLAND. A correspondent writes;—"Since the recent meeting of the National Baseball League in Birmingham, the executive council have arranged for a general introduction of baseball into England next Spring, a number of clubs in the North and Midlands having indicated an intention to take it up.”[8]

It is unclear to what extent Sadler and Roberts were already aware of efforts to introduce baseball into England when Sadler made his business trip to the US in the winter of 1889. According to one account, Roberts learnt of baseball when he came across a pamphlet promoting the sport, one of a number issued by what was known at the time as the National Baseball League (NBL) of Great Britain, but would in time become the National Baseball Association (NBA).[9]

The NBL had been established at a meeting held in London in October 1889. However, the starting point of the efforts to introduce baseball into Britain was a tour of England by two American baseball teams, the Chicago White Stockings and the ‘All-America’ team, in the spring of that year (one stop on a world tour by the two teams); this was followed by the arrival in the summer of a group of American college students tasked with teaching the game to interested local sportsmen. Both of these events were bankrolled by Albert Spalding, baseball player and team owner (of the White Stockings), co-founder of the National [Baseball] League, and president of a sporting goods company. Spalding combined a genuine love of the game with a keen commercial eye for the possibilities of becoming the sole authorised supplier of equipment to the many baseball associations he hoped to see introduced in countries around the world.[10]

The task of introducing baseball to England Spalding placed in the hands of fellow American Robert Newton Crane (1848–1927), who had been heavily involved in the organisation of college baseball back in the US, but, by 1889, was resident in Britain. Crane, a newspaperman and lawyer who would go on to become the first American to be made a King’s Counsel (KC), the highest ‘rank’ of barrister in the English legal system, was both an able administrator and an able negotiator. He entered into the effort with a very firm idea of how it was to be done: by convincing existing sports clubs of the wisdom of adding a baseball section, in line with the idea that baseball could become a summer, close-season complement to the winter sport of Association Football.[11]

Middlesbrough, with its well-established sports scene, was just the sort of place where Crane would imagine his efforts would be rewarded. Thus, it is not surprising that, when Samuel Sadler chaired a meeting in Middlesbrough in March 1890 to gauge interest in introducing baseball in the town, Newton Crane was the guest of honour, and it was he who provided the means of realising Sadler’s vision.

[Sadler] was one of those who believed that the happiness of the people was perhaps just as well encompassed by exercising their muscle and adding to their health as by some of their quack nostrums and philanthropic order. He was satisfied that if they cared to take up the American game of baseball, which he had seen played in America, they would find there was plenty of fun and sport to be extracted out of it.[12]

The two most significant decisions to come out of that March 1890 meeting were that a baseball association would be formed in the local area with Samuel Sadler on the provisional committee and Walter Roberts as its organising secretary; and that Crane’s NBL would ‘send down an expert player to put them in the way of the game’. Significantly, the provisional committee also included the secretaries of the Middlesbrough and Ironopolis Football Clubs.[13]

Things progressed rapidly from that point. Within three weeks, the ‘Cleveland and Teeside Baseball Association’ had been formed—it would change its name to the ‘Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association in June—with Sadler as its president, and Roberts was reporting that clubs ‘had been or were being formed’ by a number of local football and cricket clubs: Middlesbrough, Darlington, Eston, South Stockton, St. Augustines, and Bishop Auckland. (It is worth noting here that, although initially associated with Middlesbrough FC, Middlesbrough Baseball Club would become a separate entity in 1891.) Just as significantly, in advance of the arrival of the promised ‘expert player’, two Canadian medical students, studying at Edinburgh University, had arrived to spend their Easter vacation in the local area instructing any interested parties in the finer points of the game.[14]

The two students were named in the press as ‘T.B. Moore’ and ‘H.A. Sheffield’ of Nova Scotia. A search of UK Medical Student Registers allows us to identify them as 20-year-old Thomas Benjamin Moore (1870–1945) and 22-year-old Harry Almon Sheffield (1868–1891), both of whom had been born in Nova Scotia and had studied at Mount Allison College, New Brunswick, before travelling to Scotland to study medicine (arriving in October 1889). Moore would go on to play for the pioneering University of Edinburgh baseball team and become involved in baseball in Britain at a national level, joining the NBA’s national council as the representative for Edinburgh, before emigrating to the US in 1894. Sheffield’s story was a tragic one: he contracted tuberculosis (TB) while in the UK, prompting his return to North America; he died in a sanatorium in North Carolina in April 1891, aged just 23, attended by his physician father, Dr Mason Sheffield.[15]

Moore and Sheffield arranged practice and exhibition matches not just in Middlesbrough but in West Hartlepool, Darlington, and Sunderland, too. This would usually involve an introductory session of batting, fielding, and pitching practice, followed by a game, during which one of them would act as umpire and coach the batters and catcher, while the other coached the pitcher and fielders. In one notable game in Darlington, the Mayor of Darlington, 30-year-old Jack Pease, a member of the family of merchants and bankers that had founded not just the Stockton and Darlington Railway but Port Darlington (Middlesbrough), too, was the pitcher. This is not to say that everything went to plan: the first practice game and exhibition match in Middlesbrough attracted only 40 and 200 spectators, respectively. In what should have come as a shock to no one, the footballers among the players were terrible at fielding (poor fielding was an issue that would bedevil the game in Britain across its first 40 years of existence).[16]

At the end of April, as Moore and Sheffield were making plans to return to Edinburgh, the promised ‘expert player’ arrived in the person of James Edward Prior (1861–1937), who had played minor league baseball for the Hartford Babies back in his native Connecticut, sharing the roster with a 22-year-old Connie Mack. Prior got straight to work, including adding Newcastle Upon Tyne to the list of towns where baseball was trialed. (This was the first, tentative step in a process that would eventually lead to the formation of the Northumberland and North Durham Baseball Association in August 1891.) Prior also umpired a game between the already-established South Stockton and St. Augustines clubs in early May (South Stockton won 13–3); however, his time in the North-East was to be short, as by early June, he had been called south to guide the Stoke club in the newly formed professional National [Baseball] League.[17]

When Crane had attended the meeting to launch baseball in Middlesbrough, it had been with the expectation that the district would provide one of the teams for a planned national professional league, with another being based in Tyne and Wear. However, the NBL’s hopes of launching a true national league were dashed by the practical impossibility of organising games between teams hundreds of miles from each other while playing a sport that had yet to attract a following. Instead, the National League would in its first—and only—season comprise teams from only the North Midlands: Derby, Preston North End, Aston Villa, and Stoke. The ins-and-outs of the short existence of the National League falls outside the scope of this work; suffice to say, it all ended in acrimony over an issue that would continue to plague attempts to introduce American baseball into Britain: the presence in some teams of imported, experienced North American players.[18]

With the collapse of the National League to the south, the Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association would by accident or design remain resolutely amateur, in common with equivalent scenes in Derby, Birmingham, and London. By extension, although there would be North American players in the scene, most notably Richard and Nathan Harrison (see below), Joe Bentley, and Will Johnson,[19] it would be dominated by local players drawn from Middlesbrough’s working population.

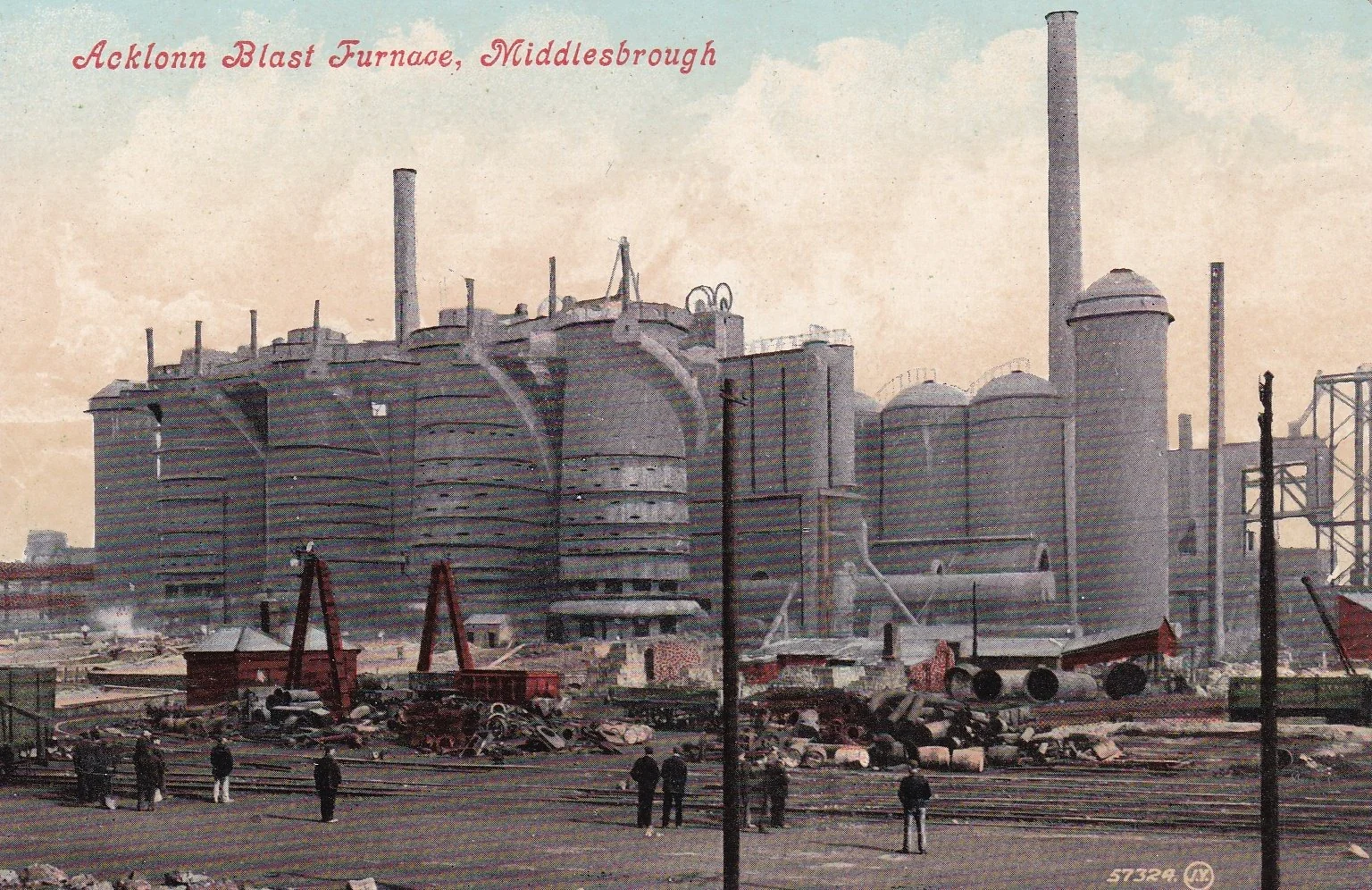

To the enterprise and energy of Messrs Bolekow and Vaughan, and their mining engineer—Mr Marley, the district is indebted for the discovery of the ore at Eston, where it is found in some places within eighteen inches of the surface; presenting a face of iron-stone, averaging twelve feet in depth, easily worked, and yielding a minimum rate of thirty-three and a half percent of excellent metal.[20]

Although the extension of the Stockton and Darlington Railway and the building of Port Darlington in 1830 had turned Middlesbrough from a sleepy little fishing village into a bustling port, it was the discovery of iron ore in the Cleveland Hills in 1850 that turned it into an industrial powerhouse, gaining it the title ‘Ironopolis’.[21] By the 1870s, one-third of all the iron being produced in Great Britain—the largest producer of iron in the world—was being produced by Middlesbrough blast furnaces. Chemical companies like Sadler’s also called the town home, and fully one-half of the working-age population was involved in manufacturing of one sort or another. [22]

It was a young, bustling, working-class town, but also an unhealthy one. By 1874, its death rate was among the worst in England, with deaths through specific diseases 1.5–2 times higher than in even other industrial cities of the North. Tuberculosis rates were also among the worst in England, and would remain so well into the Twentieth Century. In the winter before Sadler conceived the idea of bringing baseball to Middlesbrough, the town was struck by an outbreak of pneumonic plague that killed nearly 500 people (out of a population of around 55,000), more than ten times as many as died of pneumonia in normal years. Typhoid was at epidemic levels the year that Middlesbrough took up baseball; later in the decade, the same would be true of smallpox. While we cannot say that Harry Sheffield’s four weeks in Middlesbrough were when he contracted TB—he was, after all, a medical student and exposed to all sorts of communicable diseases during his studies—it would at the same time not be surprising if this was the case. It was no wonder that Walter Roberts fled to Suffolk for the sake of his wife Frances’s health.[23]

It is also no wonder that the Muscular Christian ideal, with its focus on health and physical fitness, took root in the town, and that devotees like Sadler and Roberts were keen to find sports that would catch on with the working population in the way that, for example, cricket had not.[24]

The Middlesbrough Baseball Club played a match with the Estonians at Eston on Saturday, and had to retire defeated by 29 [runs] to 22 […] The miners are becoming great adepts at the game, and if they pay more attention to their fielding, they need fear no club in the North.[25]

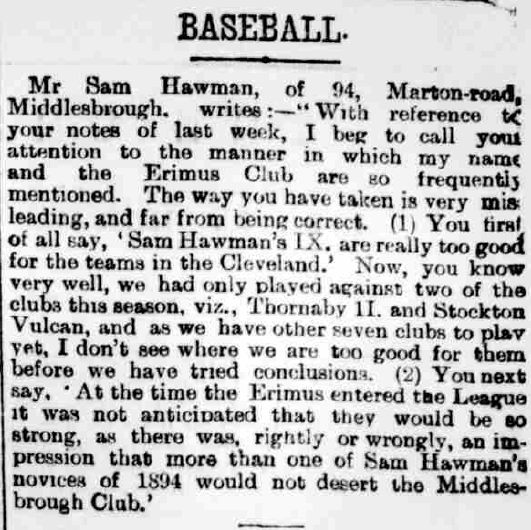

Although the Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association would not have its first overtly factory team until 1894, in small communities dominated by single industries, like the iron-mining village of Eston, teams were dominated by men with a single occupation. Inevitably, of course, many of the players from Middlesbrough itself would also be connected to the iron industry. We can take as an example a stalwart of the scene, the famously combative Samuel ‘Sam’ Hawman (1869–1930).

BASEBALL. Mr Sam Hawman, of 94, Marton-road, Middlesbrough, writes:—"With reference to your notes of last week, I beg to call your attention to the manner in which my name and the Erimus Club are so frequently mentioned. The way you have taken is very misleading, and far from being correct.”[26]

Sam Hawman was the son of a blast furnace engineer, Richard Hawman, and started work in the industry himself at age 11, joining the Anderston Foundry Company. He would spend his entire working life—50 years—working at Anderston’s. Richard Hawman was vice president of the local swimming club, so it was not surprising that young Sam would take to sports, too, becoming a runner and competitive walker.[27]

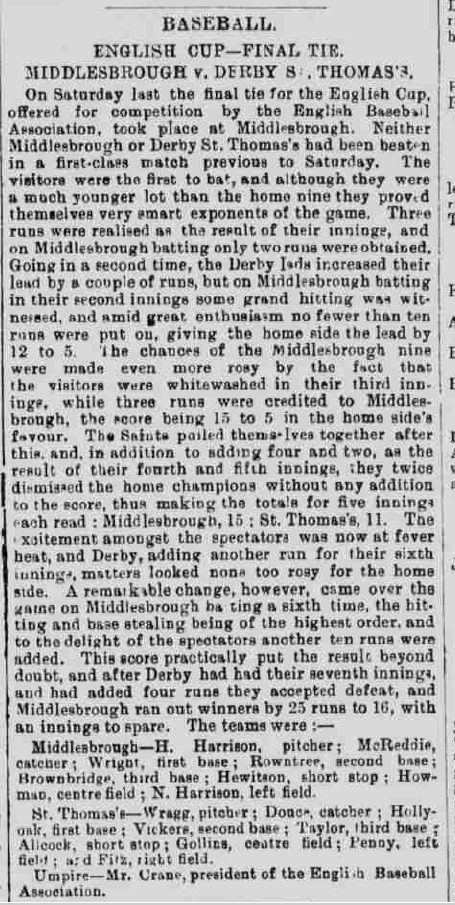

In 1891, Sam Hawman became one of the first members of the Middlesbrough Baseball Club after its separation from Middlesbrough FC. He played two seasons with Middlesbrough (1892 and 1893) at first base and centre field, and as such, was a member of the Middlesbrough team that beat [Derby] St. Thomas’s (a school team) to claim the National Championship in 1892, the apotheosis of the Middlesbrough baseball scene (for more on other players of that 1892 championship-winning Middlesbrough team, see below).[28]

In early 1894, Hawman left the Middlesbrough club to organise a works team at Anderston, the Afco (aka AFCO, AFCo) team, which played in the Cleveland and South Durham Association’s 1894 season. There is a strong suggestion that Hawman left due to dissatisfaction with the Middlesbrough club’s leadership. There then followed an extraordinary couple of years indicative of Hawman’s fiery character. In the run-up to the start of the 1895 season, Hawman disbanded the Afco team and rejoined the Middlesbrough club, taking the Afco players into the Middlesbrough club with him, placing some in the first team, but most in the reserves. He did this, he later said, ‘to reinforce the Middlesbrough Club, as they were short of players’ (on this, see below). Although the season was very successful from Hawman’s point of view—the team were runners-up in the league, and Hawman achieved a batting average of .558—in what should have come as a shock to absolutely no one, tensions between the existing Middlebrough Club players and the former Afco players, and between the former Afco first team players banished to the Middlesbrough reserves and Hawman, were high.[29]

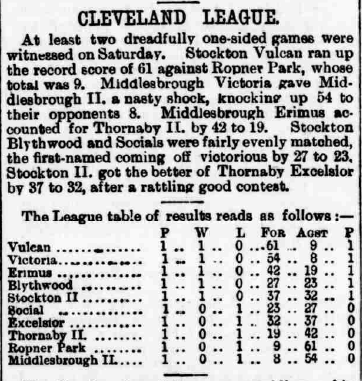

At the close of the 1895 season, in the face of continuing tensions, Hawman left for a second and final time, taking most of the former Afco players with him. In March 1896, he formed the Erimus Baseball Club (‘Erimus’, Latin for ‘We Shall Be’, was the motto of the town of Middlesbrough; the club’s colours were red caps, white shirts, and blue pants). In a further move that was greeted with dismay locally, Hawman opted to join not the top tier in the local baseball scene, where his new club would have had to face off against his old one, but the second tier. Early in the season, Erimus looked like they were on their way to being dominant—in the words of a local newspaper columnist, ‘It seems rough that a team numbering several players who played in first-class company for two or more seasons, should now be engaged snuffing out the pretensions of second-class players.’[30]

In the event, Erimus could only manage a second-place finish in the 1896 Cleveland and South Durham league season, with 8 wins and 2 losses, and it was the Stockton Blythwood team who were dominant, winning the league without losing a game. Furthermore, in an event that appears to have been greeted with glee in the local area, when Erimus met Hawman’s old team of Middlesbrough in the first round of the National Cup in early July, they received a fearful drubbing, losing 41–9.[31]

The Erimus team folded at the end of the 1896 season. Hawman umpired at least one game in the 1897 Cleveland and South Durham League season, but his playing days were over. In later years, he became a shareholder of Middlesbrough FC, coming down on the opposite side of the leadership in a number of disputes. In June 1930, two days after a typically contentious shareholders’ meeting, he took ill and died, aged 61.[32]

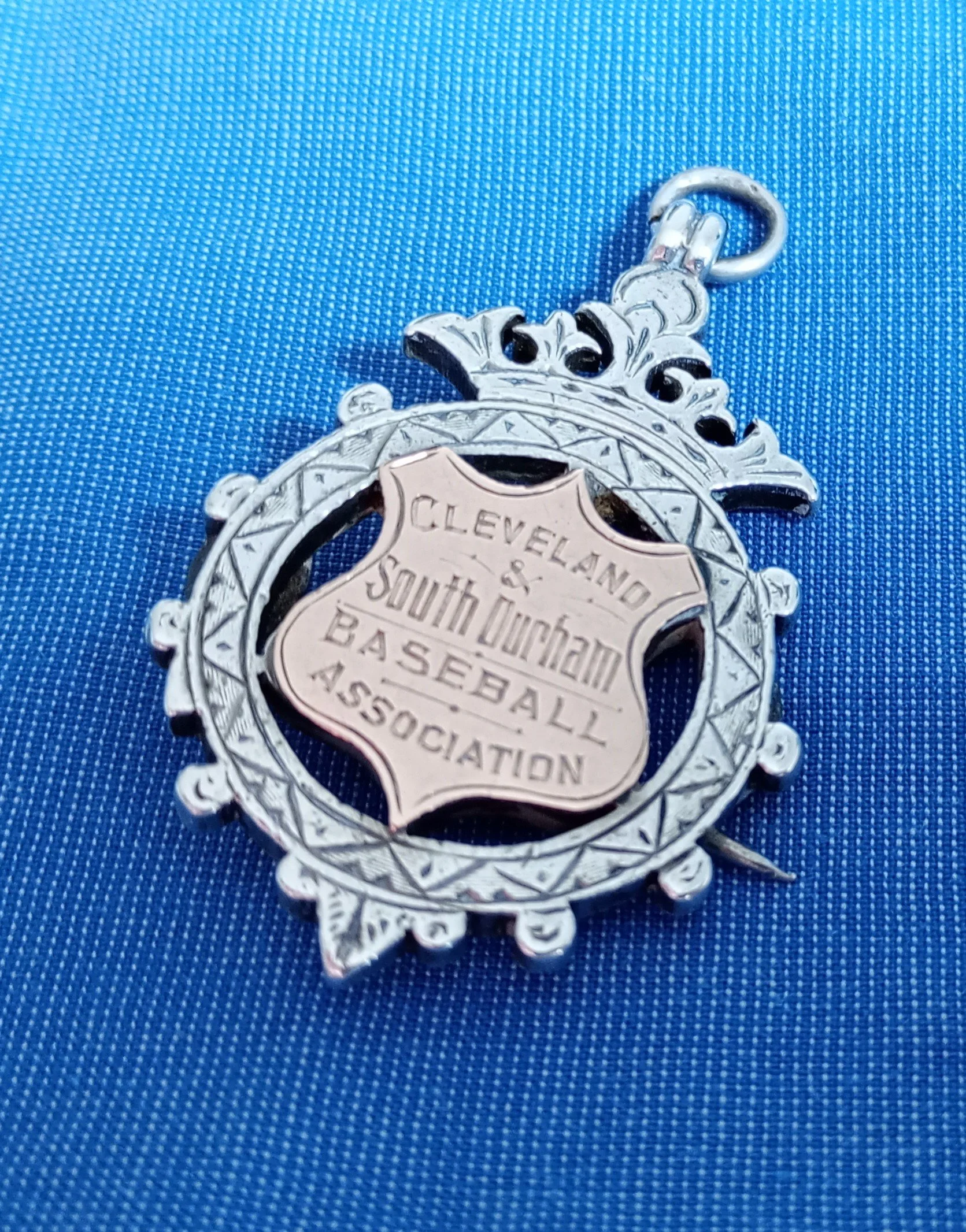

To reinforce this point regarding the ‘typical’ Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association player, it is worth referring to a rare surviving artefact from the heyday of the association. In August 2025, an item was put up for auction on eBay with the following description:

Victorian silver watch chain fob with gold washed and engraved shield to the front.

Engraved to the front - CLEVELAND & South Durham BASEBALL ASSOCIATION.

Engraved to the back - T.P. Cotton 1895.

Hallmarked for Birmingham 1895 and also stamped with the makers mark for Vaughton & Sons.

Approximately 38mm x 25mm in size.

Weight approximately 11.2g.[33]

Research points to this being a runner-up medal fob for the 1895 Cleveland and South Durham League season (medals and cup donated by Samuel Sadler). As we have already discussed, Middlesbrough were runners-up that season, and the team featured Sam Hawman and a number of former Afco Baseball Club players. Armed with this information, we can identify ‘T.P. Cotton’ as Tom Cotton, one-time pitcher with the Afco team and left-fielder for Middlesbrough in the deciding game against Stockton at the close of the 1895 season (Middlesbrough lost, 24–17). When Sam Hawman left Middlesbrough for a second time to form Erimus, Tom Cotton went with him, and when Erimus folded at the end of the 1896 season, Tom Cotton transferred to the Victoria Baseball Club for the 1897 season, catching at least one game.[34]

Can we go further? I think, yes. I think that we can identify Tom Cotton/T.P. Cotton as Thomas Priestley Cotton (1874–1923). This is based on a combination of the name and initial, residence, and occupation. Thomas Priestley Cotton was born in 1874 in Liverton Mines, a village in the Cleveland Hills, so-named for the ironstone mining company for which the majority of the men of the village worked. His father was William Cotton, a mining engineer. By 1897, when he married Clara Ann Hansell, Tom Cotton was living in Middlesbrough and working as a ‘fitter’; based on information in the 1901, 1911, and 1921 census returns, we can expand on this to say he was working as an engine fitter for an iron foundry (by 1921, Bolckow, Vaughan & Co, but we can suppose that in 1894, it was the Anderston Foundry Company). He died in 1923 at what to us is the young age of 49, but which to the people of Middlesbrough was commonplace. The cause of death was a cerebral tumour.[35]

The above is not to say that all of the men involved in the Cleveland and South Durham baseball Association were connected to the iron industry. To provide a broader view of the scene, it is instructional to take a look at the team that achieved more than any other: the National-Cup-winning 1892 Middlesbrough Baseball Club Team, centred on its captain, Richard C. Harrison.

Here is the 1892 team:— Wm. MacReddie. catcher; R. C. Harrison (capt.), pitcher; E. A. Wright, first base; O. L. Rowntree, second base; J. H. Hewitson, short stop; R. F. Brownbridge, third base; A. H. Easton, right field; Sam Hawman, left field; Nathan Harrison, centre field.[36]

The apotheosis of the Victorian Middlesbrough baseball scene was the triumph of the Middlesbrough Baseball Club in the 1892 National Challenge Cup final, albeit playing on home ground, in front of a partial crowd, and in appalling weather against a team of schoolboys. That same season, Middlesbrough also won the Cleveland and South Durham League (the Spalding Cup) and were gold medalists at the annual baseball invitational tournament at the Newcastle Temperance Festival, shutting out an Edinburgh University team featuring Tom Moore along the way. Their record for the season was 14 games won and no games lost.[37]

It is worth delving into the makeup of this 1892 Middlesbrough Baseball Club team, as it featured several stalwarts of the Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association, men who were there at the start and still there at the finish, and presents an overview of the types of men that the game attracted.

We have already met the fiery Sam Hawman. The team’s two most prominent members were the Harrison brothers, Dick and Nate (Richard Claremont Harrison (1870–1946) and Nathan Courtney Harrison (1874–1952)). Unusually for the Middlesbrough baseball scene, the Harrison brothers were American, born in Pennsylvania, albeit to English parents (John and Annie Harrison; John Harrison was a stone mason by trade), and raised in Canada (New Brunswick). The family, which included two more brothers, John (who had been born in England before the family emigrated to the US) and George (born in the US), settled in Middlesbrough sometime between 1887 and 1889. It seems by this point that the father, John Harrison, was dead; certainly by 1891, Annie was a widow and the head of the household. Undaunted, the Harrison brothers, despite their young age, with typical Yankee enterprise, established the Harrison Brothers Diamond Grit Company in the town, a manufacturer of abrasives and shot. By 1891, all four brothers, including 17-year-old Nate, were partners in the business.[38]

As the Harrison family moved to Canada (New Brunswick) in 1875 and left for England sometime between 1887 and 1889, it is fair to say that Dick (born 1870) and Nate (born 1874) learned their baseball in Canada. Although still teenagers when they left Canada, it is also fair to say that the pair had a physiological–psychological advantage over nascent English players as boys who had grown up playing the game. This advantage served them and their teams well when they took up the game in their new home. This was particularly true of Dick Harrison in his role as pitcher for the Middlesbrough team.

Dick Harrison—described as a 'Canadian’—made his debut for Middlesbrough in June 1891 as club captain and lead pitcher. In a notable friendly game that season, Harrison pitched the team to a narrow defeat (13–14) against a team formed of Canadian and American Association Football players who were on a footballing tour of Britain and Ireland (the tour was a miserable failure). Although not definite, he was also almost certainly the player who pitched a shut-out game against an Edinburgh University team in June 1892, reputedly the first shut-out game of baseball in Britain.[39]

Dick Harrison continued as captain and pitcher into the 1893 season, which, as a result of the loss of some key players—see below—was to be a disappointment compared to the 1892 season; although the team won far more games than it lost (14 wins, 6 losses, 4 draws), it ended the season without any cups or gold medals. (As an aside, in a measure of how variable the fielding was in baseball in Britain in this period, across those 14 wins, the team scored 361 runs, and had 189 runs scored against it!). Despite the addition of some key new players, prime among them the Bach brothers, including Association Football player Phil Bach, the 1894 season was even more of a disappointment for Middlesbrough. Truth be told, by this time, Stockton had become the dominant team in the Cleveland and South Durham League, winning back-to-back titles. One reason for this further loss of form was that Dick Harrison was no longer pitching for the club, playing instead at centre field and shortstop. This may indicate that the ‘serious illness’ that kept him out of the 1895 season altogether, effectively ending his baseball career, had already begun to affect him. He would return for the 1896 season, but only to play in a reconstituted 1892 Middlesbrough team in a charity match against the 1896 side. Like all the Harrison brothers, Dick would eventually return to live in the US, in his case in 1915. He died in Massachusetts in 1945.[40]

Nate Harrison was just 18 when he played in the 1892 Championship-winning Middlesbrough team (although this was still older than all but one of the losing St Thomas’s team). Somewhat in the shadow of big brother, Dick, Nate made a spectacular ‘break for freedom’ in 1893, leaving the Middlesbrough club to form the Ironopolis Baseball Club, alongside fellow 1892 championship-winning team member Albert Henry Easton (1867–1923). Easton was the son of fruit merchant William Henry Easton, who was a director of the Middlesbrough Ironopolis Football Club, Middlesbrough’s professional football club (as opposed to the amateur Middlesbrough FC), and the baseball club was formed in association with the football club. Easton followed his father into the family business.[41]

Although Albert Easton would remain with the Ironopolis team, Nate’s time there was short, as he was back in the Middlesbrough team for the 1894 season. However, like his brother, Dick, Nate would sit out the 1895 season, making 1894 his last season in Middlesbrough baseball, returning only for that charity game in 1896. In Nate’s case, this was because he spent 1895 in the US, helping to set up what would become an American arm of the Harrison Brothers Diamond Grit Company. He was among the first of the brothers to relocate to the US, making the country his permanent home as early as 1900, when, in a further bid for independence, he founded his own abrasives company, the Harrison Supply Company. Alas, although the company prospered initially, it folded in 1922, and Nate became embroiled in a lawsuit over the true ownership of shares in the company said to belong to his wife. He died in New Hampshire in 1952.[42]

Another of the championship-winning team with an Ironopolis FC connection was Dick Harrison’s battery mate, Scotsman William McReddie (1870–1935). McReddie was a professional footballer and played for Ironopolis FC when the club was at its peak, winning back-to-back trophies in the Northern League. This makes him a rare Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association player who fulfilled Newton Crane’s ambition for the game: attracting professional footballers looking for a sport to keep them in trim in the off-season. McReddie spent most of the 1893 baseball season back home in Scotland. However, for the 1894 season, he captained the Ironopolis baseball team.[43]

McReddie’s movements during the 1895 and 1896 seasons are not certain. However, he returned for the 1897 season, the only member of the 1892 team to do so. As such, he became the only member of the Middlesbrough club to play in two National Championship finals, turning out for the Middlesbrough team that lost to Derby in the 1897 final. Earlier in the season, he was struck in the chest by the ball and had to be carried off the pitch in a faint. Rather than being seen by a doctor, he was simply carried to a friend’s house to recuperate. Different days. It is worth noting here that there appears to be some confusion between ‘Wallace McReddie’ and ‘William McReddie’; however, that the ‘W. McReddie’ who played football for Ironopolis FC, was the baseball player, ‘Wm. McReddie’, on the one hand, and that his given name was William, on the other, can be confirmed from newspaper reports of the time and census returns.[44]

To continue the football theme, John Henry Hewitson (1866–1949), although an iron moulder by trade, was also an amateur footballer, turning out for Middlesbrough Grange FC in 1892/3 and Middlesbrough FC in the 1894/5 and 1895/6 seasons. He remained with the Middlesbrough Baseball Club until at least the 1895 season, albeit starting in the reserves that season. Interestingly, by 1921, he was a timekeeper at the Anderston Foundry Company, making him a colleague of Sam Hawman.[45]

Oswald Lambert ‘Ossie’ Rowntree (1868–1936), AKA ‘Slugger’, was the big hitter of the 1892 Middlesbrough team. He was a landscape gardener by trade, tending to the gardens of Sir Thomas Wrightson, MP for Stockton, for many years, before entering the employ of W.J. Nimmo, chairman of the Castle Eden Brewery. He also laid out the Castle Eden Golf Course. He was another of the 1892 Middlesbrough side who played through to the 1894 season, but was absent for the 1895 season. However, unlike many of the other players, he returned for the 1896 season.[46]

Robert Foster Brownbridge (1863–1934), the old man of the 1892 team, was a cabinet maker by trade in the employ of the Lithgow and Storry company. He was a rare member of the 1892 team who stayed with the club all the way through to 1896, even appearing on the roster for the 1895 ‘Sam Hawman’ Middlesbrough team.[47]

There is some confusion as to the ordering of the given names of ‘Alf Wright’, the 1892 Middlesbrough team’s first baseman, making his identification as Alfred Edward Wright (1870–1943) tentative. Alf Wright was Middlesbrough’s deputy captain as well as first baseman, and another of the 1892 team whose final full season was the 1894 season. Alfred E. Wright was a plater in a shipyard by trade.[48]

As the above makes clear, the 1892 Middlesbrough team, the Harrison brothers aside, represented a broad cross-section of Middlesbrough’s working-class workforce: iron industry workers (Hawman and Hewitson), tradesmen (Easton, Rowntree, and Brownbridge), a shipyard worker (Wright), and a professional football player (McReddie). The Harrisons really were the outliers—factory owners, not factory workers, American, not British—but they already had a love of the game before they joined the team, fostered since childhood (Nathan Harrison was arguably still a child); they had a different stake in the game.

These were exactly the men that Sadler and Roberts had hoped to interest when they launched baseball in Middlesbrough. In that respect, their efforts were met with success. However, alas, the scene was not to last.

NO ROOM FOR BASEBALL It would appear that the energetic work of the few missionaries who have been actively engaged for some years in endeavouring to popularise the American game of baseball in this country is destined to bear little if any fruit.[49]

In the six years from 1892 until 1897, teams from the Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association appeared in no less than four National Cup Finals: Middlesbrough in 1892 and 1897 (one win, one loss), Darlington St. Augustine’s in 1893 (loss), and Stockton in 1894 (loss). If one broadens the area of search to include the Northumberland and North Durham Baseball Association, the only year when there wasn’t a North-East team in the National Cup Final was 1895 (Wallsend won the Cup in 1896).[50]

It is somewhat ironic then that 1895 was, in most regards, when the game was at its most popular in the North-East, with the Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association able to stage two leagues. And, yet, two years later, the scene would effectively be dead—clubs like Middlesbrough would continue, kept going by a small group of devotees, but the game ceased to have any meaningful presence in the sporting calendar of the region.

What went wrong? On one level, it simply reflects the failure of the game to gain a foothold in the sporting life of Britain as a whole. The reasons for this have been much discussed (not least by me[51]) but boil down to the uphill struggle any new sport faced in trying to find a place in an already crowded sporting calendar, coupled with elements of the game (principally, three-out-all-out) that British sports fans could not/would not adjust to. However, there are also local factors to consider.

Prime among the latter is what happened between the end of the 1895 season and the start of the 1896 season. Buoyed by the success of the 1895 season, the officials and backers of the Cleveland and South Durham and Northumberland and North Durham Baseball Associations decided to seize their moment and pool their efforts to launch a new, national league. What role, if any, the National Baseball Association played in this is uncertain. Called once more, simply, the ‘National League’, the new league launched in May 1896 with just six teams, all from the North-East, three from the Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association—Middlesbrough, Stockton, and Thornaby—and three from the Northumberland and North Durham Baseball Association—Wallsend, Clara Vale, and Walker.[52] The hope was, of course, that the league would expand to include teams from outside the North-East in subsequent years. However, although baseball was certainly more established in 1896 than when the last attempt at a national league had been made in 1890, the reality was no different: the sport commanded too little support from paying spectators for it to be practical for teams and their supporters to travel long distances for regular league games (compared to one-off challenge cup competition matches). It folded after only one season. Plus ça change.

(As an aside, on the issue of long-distance travel to play games: the generally accepted view of Wallsend’s victory in the 1896 National Cup final against the more-fancied Remington team is that this was in large part due to Remington having to travel all the way from London to Stockton, a distance of 260 miles, the day before (a 7+ hour train journey[53]), and then play the semi-final they were involved in, against Stockton, and the final on the same day, Saturday 15 August 1896. Following a grueling three-and-a-half-hour semi-final match against Stockton, Remington had to immediately take the field against Wallsend. Four innings into the game, with their players visibly exhausted and light failing, the Remington team asked for play to be suspended until the following Monday. Wallsend refused. Remington went on to lose the game.[54])

At the same time, the [second] National League, which was effectively just a North-East Super League, had a profound and ultimately negative effect on the rest of the North-East baseball scene. As with super leagues in sports all throughout modern history, it drew talent and investment away from smaller clubs and opened up a skill gap between the top and lower tiers of the game. (It was to avoid competing in the National League against bigger teams that Sam Hawman opted to place his new Erimus team in the now second-tier Cleveland and South Durham Baseball League.) With the cream of the two North-East associations playing against each other, they only improved, while the other teams in the two associations’ leagues lost their chance to improve their game by playing against the best teams in the local area [before those teams became too good to play against].[55]

This all came to a head when, after the inevitable failure of the National League after only one season, the three Cleveland and South Durham clubs in the league rejoined the top tier of the Cleveland and South Durham League for the 1897 season.

Owing to the play of the first three clubs in the Cleveland and South Durham League being so much superior to the others, the interest in the League games was practically gone before the season was half through, and the Council would like the opinion of the representatives present as to how to form a league or competition on a new basis which would keep the interest up until the end of the season.[56]

The North-East baseball scene had tried to run before it could walk. The result was inevitable. However, the ultimate failure of the scene, along with its relatively short existence as a popular sport (in comparison to other sports; seven years was arguably the longest time that any American baseball effort in Britain had retained any great degree of popularity, beyond a few hundreds of devotees, before the 1930s[57]), should not be allowed to overshadow the role it played in furthering the growth of a sporting culture and the pursuit of physical recreation in Middlesbrough, a town that desperately needed to do something to improve the health of its working population. It is telling in this respect that the following decade, the first of the Twentieth Century, would see the emergence in Middlesbrough of work-based sports and recreation clubs that, rather than being centred on a single sport or pastime, offered their members a range of activities to pursue; a model that allowed niche sports like baseball (and sport for women) to thrive in a way that would not have been possible a decade earlier. Baseball played its part.[58]

Jamie Barras, August 2025

Back to Diamond Lives

Notes

[1] Principally, but not restricted to the following:

1. Catherine Budd ‘The Growth of an Urban Sporting Culture : Middlesbrough, c.1870-1914’, Thesis submitted for PhD, De Monfort University, 2012.

2. Catherine Budd, ‘A sport for the “Yankee-like enterprise and energy of Ironopolis”: Baseball in late nineteenth century Middlesbrough’, Cleveland History, 2013, 104, 23-30

[2] https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-health-friendship-and-baseball, accessed 28 August 2025.

[3] ‘North Country News: Baseball’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 12 March 1890.

[4] Details of Samuel Sadler’s life: ‘Obituaries: Sir Samuel Sadler’, Times, 30 September 1911. The best description of the involvement of Francis Ley with baseball in Britain is to be found in Joe Gray, ‘What About the Villa?’ (Ross-on-Wye: Fineleaf Books, 2010), 37–43. Francis Ley was inducted into the British Baseball Hall of Fame in 2010.

[5] Walter Roberts’ full name: ‘Middlesbro’ Topics: The New Mayor’, Stockton and Thornaby Herald, 10 November 1906. Years of birth and death of Walter Garibaldi Roberts: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/, accessed 28 August 2025. Organising secretary, Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association: ‘Baseball in Middlesbrough’, Northern Echo, 26 March 1890. Council member, National Baseball League: ‘Important Baseball Meeting in Birmingham’, Ulster Football and Cycling News, 18 July 1890. Organisating secretary, Baseball Association of Great Britain: ‘English National Baseball Association’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 17 August 1891; Treasurer of National Baseball Association: ‘Baseball’, Northern Echo, 24 March 1893.

[6] Sadler, 17 clubs: Budd, Note 1 above, second reference. Roberts, president of local YMCA: ‘Mayora “At Home”’, Stockton and Thornaby Herald, 23 January 1909. Roberts, ‘Minority of one’: Note 5, first reference.

[7] Walter and Frances move to Suffolk for Frances’ health: ‘The Old Year and the New’, Stockton and Thornaby Herald, 31 December 1910. Farming in Suffolk: entry for Walter Garibaldi Roberts, Huntingfield District, 1911 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations. Years of birth and death and maiden name of Frances Roberts: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/, accessed 28 August 2025.

[8] ‘Baseball in England’, Sporting Life, 4 December 1889.

[9] This is the story recounted by Gray, Note 4 above, second reference, pge . Interesingly, Gray makes no mention of Sadler.

[10] For the story of the 1889 tour, Spalding, and the NBL, see Gray, Note 3 above, second reference..

[11] I discuss Crane’s involvement in promoting baseball in Britain here: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-intolerance, accessed 28 August 2025. He was inducted into the British Baseball Hall of Fame in 2024.

[12] ‘Baseball in Middlesbrough’, Northern Echo, 26 March 1890.

[13] See Note 12 above.

[14] Cleveland and Teeside, Moore and Sheffield, etc.: ‘Baseball’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 17 April 1890. Name change to Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association: ‘Baseball’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 19 June 1890.

[15] Entries for Thomas Benjamn Moore and Harry Almon Sheffield, UK, Medical and Dental Students Registers, 1882-1937; Moore emigrates to US: entry or Thomas Benjamin Moore, 1894, U.S., Naturalization Records, 1840-1957; Death of Sheffield, cause of death, father attending: entry for Harry Sheffield, 20 April 1891, New Brunswick, Canada, Deaths, 1888-1938, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 28 August 2025. Moore, captain of Edinburgh University baseball team: ‘Baseball’, Derby and Chesterfield Reporter, 21 August 1891. Moore on council of NBA: See Note 5, fourth reference.

[16] Baseball in Sunderland: ‘American Baseball’, Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette, 29 April 1890. Moore and Sheffield’s approach to coaching and game in West Hartlepool: ‘Baseball’ North Star (Darlington), 24 April 1890. Jack Pease pitching, game in Darlington: ‘Baseball, Northern Echo, 19 April 1890. Not everything went smoothly: Baseball Makes Slow Progress’, Northern Weekly Gazette, 26 April 1890.

[17] J. E. Prior, Hartord Baseball Club: ‘Baseball’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 20 May 1890. Prior and Connie Mack: https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=f4aea09d, accessed 28 August 2025. South Stockton–St. Augustine’s game: ‘Baseball’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 13 May 1890. Prior with Stoke: ‘American Baseball’, Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette, 17 June 1890. Formation of Northumberland and North Durham Baseball Association: ‘Baseball’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 14 August 1891.

[18] See Gray, Note 4 above, second reference, for the full story.

[19] For Bentley and Johnson, see, ‘Baseball: Provincial’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 5 June 1896.

[20] ‘Opening of the Eston Iron Mines’, Darlington & Stockton Times, Ripon & Richmond Chronicle, 11 January 1851.

[21] The earliest reference to the ‘Ironopolis’ name for Middlesbroug that I can find is from 1868: ‘A Royal Visit and Princely Gift’ Newcastle Chronicle, 15 August 1868. ‘Royalty has visited the centre of Ironopolis, and passed a fitting encomium upon an instance of public-spirited munificence such as is rarely witnessed.’ This is is reference to the opening of Albert Park In Middlesbrough.

[22] See Budd, Note 1 above, first reference, and references therein.

[23] Victoria Ann Brown, Public Health Issues and General Practice in the Area of Middlesbrough, 1880-1980. Doctoral thesis, Durham University, 2012. Available at: https://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4937/, accessed 28 August 2025.

[24] Middlesbrough and cricket: Budd, Note 1, first reference, pages 66–68 and 259–265.

[25] ‘Baseball at Eston’, Northern Weekly Gazette, 31 May 1890.

[26] ‘Baseball’, Northern Weekly Gazette, 6 June 1896.

[27] Details of Sam Hawman’s life from his obituary: ‘Tee-Side Sportman’s Death’, South Bank Express, 14 June 1930. Richard Hawman, vice-president swimming club: Budd, Note 1 above, first reference, page 197. Familial connection between Richard Hawman and Sam Hawman: entry for Richard Hawman, Middlesbrough district, 1871 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 29 August 2025.

[28] Hawman member of 1891 Middlesbrough Baseball Club: ‘Middlesbrough Baseball Club’, York Herald, 5 October 1891. In 1892 team: ‘Baseball’, York Herald, 21 May 1892. At first base in 1893 team: ‘Baseball’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 4 August 1893.Hawman at centre field in the team that beat St. Thomas’s to take National Cup, 1892: ‘Baseball: Final of the English Cup’, Leeds Mercury, 29 August 1892. It is worth noting that Derby St. Thomas’s’ had no connection to Francis Ley’s Derby team that played in the professional National League in 1890. St. Thomas’s was a Derby school team of players aged between 16 and 18: William Morgan, ‘Baseball In Derby (II)’, Baseball Mercury, Issue 22, April 1983, https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/misc/mercury/issue_22.pdf, accessed 29 August 2025.

[29] This is Hawman‘s own account of events, taken from a letter he wrote to the local papers in 1896: See Note 26, above.

[30] Continuing with Hawman’s own account, Note 25, above. Columnist comments on Erimus baseball team: ‘Baseball’, Northern Weekly Gazette, 30 May 1896. Hawman’s 1895 season batting average: ‘Middlesbrough Baseball Club’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 10 April 1896. Middlesbrough runners-up 1895 season: ‘Baseball’, York Herald, 5 August 1895. ‘Erimus’: https://www.middlesbrough.gov.uk/council-and-democracy/civic-and-ceremonial/middlesbroughs-coat-of-arms/, accessed 29 August 2025. Formation of Erimus Baseball Club, and team uniform colours: ‘Baseball Notes’, Northern Weekly Gazette, 7 March 1896.

[31] Stockton Blythwood dominant: see league table: ‘Baseball’, Northern Weekly Gazette, 25 July 1896; Middlesbrough crush Erimus: ‘Baseball: National Cup—First Round’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 3 July 1896.

[32] Hawman, umpire, 1897: ‘Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Assocition’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 15 June 1897. Sam Hawman’s death: see Note 27 above, first reference.

[33] Taken from the original ebay.co.uk listing, Running Dog Antiques, runningdogantiques@googlemail.com, eBay item number 127322608613, August 2025.

[34] Tom Cotton, usually listed as ‘T. Cotton’, pitching for Afco in 1894: ‘Baseball: Middlesbrough V. A.F.CO. (Anderston Foundry Co)’, Daily Star (Darlington), 5 May 1894; In the Middlesbrough team at left field versus Stockton, 1895: ‘Baseball: Stockton V. Middlesbrough’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 2 August 1895; in Erimus, 1896 (named as ‘Tom Cotton’): See Note 30 above, second reference; in Victoria team, 1897: ‘Baseball’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 28 May 1897.

[35] The information on the life of Thomas Priestley Cotton is derived from: England Census returns for Thomas Cotton/Thomas Priestley Cotton/Thomas Priestly Cotton, for 1901, 1911, and 1921, all Middlesbrough district; marriage register entry for Thomas Cotton and Clara Annie Hanswell, 1897, Teesside, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1939: ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 23 August 2025; certified copy of the death certificate of Thomas Priestly Cotton, digital image obtained from General Register Office, August 2025.

[36] See Note 29 above, second reference.

[37] National Cup win: see Note 28 above, final reference. Record of season: ‘Baseball Club’, Yorkshire Evening Press, 3 October 1892. Shut-out game: ‘Newcastle Temperance Festival: Baseball’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 23 June 1892, and Note 30 above, second reference. The result was 4–0, an unusually low-scoring game for baseball in England at the time, reflecting the quality of the fielding of the Edinburgh team, almost certainly all, like Tom Moore, North American medical students.

[38] Information on the lives and movements of the Harrison family obtained from: 1881 Canada Census, St John, New Brunswick district, entry for Nathan C. Harrison; 1891 England Census, Middlesesbrough district, entry for Annie Harrison and family; passport application of Nathan C. Harrison, 21 May 1924, U.S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925: ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 29 August 2025. ‘Ex-Borough Baseball Captain’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 30 June 1939.

[39] Dick Harrison ‘Canadian’: ‘Baseball: Middlesbrough V. St Augustine’s’, York Herald, 22 Jun1891. Game against Canadian and American Association Football team: ‘Baseball: Middlesbrough V. Canadians’, North Star (Darlington), 4 September 1891. Canadian–American tourists dismal failure: ‘Sports and Pastimes’, Midland Daily Telegraph, 11 January 1892. Shut-out game, reputedly first in British baseball: Note 30 above, second reference.

[40] Dick Harrison pitching 1893 seaon: ‘Baseball’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 4 August 1893. Record of 1893 season: ‘Middlesbrough Baseball Club’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 25 September 1893. Harrison at right field and shortstop, 1894 season: ‘Sports and Pastimes’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 7 June 1894; ‘Baseball’, Northern Echo, 30 June 1894. ‘Serious illness’ 1895 and 1892 team reconstituted 1896, see Note 30 above, second reference.

[41] Nate Harrison and Albert Easton founding the Ironopolis Baseball Club: See Note 26 above, second reference, and ‘Baseball: Middlesbrough V. Ironopolis’, Nothern Echo, 19 June 1893. Story of Ironopolis FC: Budd, Note 1, first reference, pages 93–151. Biographical details for Albert Easton: entry for William Easton, Middlesbrough district, 1891 England Census, entry for Albert H. Easton, Middlesbrough district, 1901 England Census. Year of death: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 30 August 2025.

[42] Nate Harrison back in Middlesbrough team,1894: See Note 39 above, third reference. Albert Easton still in Ironopolis team: ‘Sports and Pastimes’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 1 June 1894. Nate back in US 1895: Note 37 above, third reference. Year of death: Nathan Courtney Harrison (1874–1952) • Person • Family Tree, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 29 August 2025. Story of Harrison Supply Company: https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/6565695/first-national-bank-v-harrison/, accessed 30 August 2025.

[43] McReddie back home in Scotland for most of 1893 baseball season: Note 30 above, second reference. Captaining Ironopolis team for 1894 season: ‘Sports and Pastimes’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 1 June 1894.

[44] In 1897 final-losing team: ‘Baseball: Final for the English Cup’, Derby and Chesterfield Reporter, 3 September 1897. Fainting incident: ‘Baseball’, North Star (Darlington), 31 May 1897. McReddie, footballer, and McReddie, baseballer, same person: T.T. Mac, ‘Newcastle and Middlesbro’ Gossip’, Scottish Referee, 1 August 1892. William McReddie, professional football player, 1891 England Census, Middlesbrough, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 29 August 2025.

[45] Information on John Henry Hewitson/John H Hewitson: 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911, and 1921 England Census returns, Middlesbrough district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 29 August 2025. Year of death: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 30 August 2025. ‘J. Hewitson’ playing for Middlesbrough Grange FC 1893: ‘Football: Association Notes’, North Star (Darlington), 11 February 1893. ‘J. Hewitson’ playing for Middlesbrough FC 1894: ‘Football’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 14 September 1894. ‘Hewitson’ playing for Middlesbrough FC 1895: ‘Football’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 13 December 1895. Hewitson in1895 Middlesbrough baseball reserves: ‘Baseball’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 3 May 1895.

[46] Biographical information for Ossie Rowntree: ‘Blackhall: The Late Mr O. L. Rowntree’, Northern Daily Mail (Hartlepool), 29 July 1936; 1891 England Census, Middlesbrough, entry for Oswald L. Rowntree, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 29 August 2025; Note 30 above, second reference. In Middlesbrough club 1894: ‘Baseball’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 11 May 1894. In 1896 team: See Note 26 above, second reference, and ‘Baseball’, North Star (Darlington), 22 July 1896.

[47] Biographical information for Brownbridge: 1891 England Census, Middlesbrough, entry for Robert F.Brownbridge, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 29 August 2025. Year of death and full name: ‘Mr R.F. Brownbridge: Death Recalls Middlesbrough’s Baseball Days’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 20 July 1934. In 1895 team (reserve): Note 34 above, third reference; in 1896 team: Note 44 above, final reference.

[48] ‘Alf Wright’ and ‘E.A. Wright’ given-name order: Note 30 above, second reference; ‘A.E. Wright’ given-name order: Baseball’, York Herald, 21 May 1892. Biographical information for Alfred Edward Wright: entry for Alfred E Wright, 1891 and 1901 England Census returns, Middlesbrough district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 29 August 2025. Year of death: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 30 August 2025. In 1894 Middlesbrough team: Note 45 above, fourth reference.

[49] ‘No Room For Baseball’, North Star (Darlington), 19 June 1897.

[50] For a list of National Champions and Runners Up, see Project COBB: https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/national_champions.html, accessed 30 August 2025.

[51] https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-intolerance, accessed 30 August 2025.

[52] ‘Popular Pastimes: Baseball’, Shields Daily Gazette, 14 March 1896.

[53] This calculation is based on it taking 7 hours to travel from London to Newcastle by train in this period: https://www.campop.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/transport/onlineatlas/railways.pdf, accessed 31 August 2025.

[54] ‘Baseball: The National Cup Competition’, Jarrow Express, 21 August 1896.

[55] ‘Cleveland Baseball Association’, North Star (Darlington), 25 March 1898

[56] Note 55 above.

[57] The distinction ‘American Baseball’ needs to be made here, because the uniquely British niche variant, ‘English Baseball’ remained popular for nearly 100 years in its heartlands of Liverpool and South Wales: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-health-friendship-and-baseball-part-ii, accessed 31 August 2025.

[58] See Budd, Note 1 above, first reference, pages 266–272, for the rise of sports and recreation clubs in 1900s Middlesbrough.

Samuel Sadler 'the Francis Ley of the Middlesbrough baseball scene'. Postcard, public domain.

Walter Garibaldi Roberts, organising secretary of the Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association. Stockton Herald, 11 May 1912. Image created by the British Library Board. Public domain.

The Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association's second tier, 1896 season. Early baseball in Britain was bedevilled by the problem of poor fielding leading to high scores. Northern Weekly Gazette. Image created by the British Library Board. Public domain.

Sam Hawman makes his opionion known. Northern Weekly Gazette, 6 June 1896. Image created by the British Library Board. Public domain.

Game report, the 1892 National Championship Final. Derby Mercury, 31 August 1892. Image created by the British Library Board. Public domain. Middlesbrough's pitcher was not 'H. Harrison' but 'R.C. Harrison', an American who learned his baseball in Canada.

Acklam Ironworks, Middlesbrough. Postcard, author's own collection.

1895 Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association runner-up medal fob (?), Tom Cotton, Middlesbrough Baseball Club. Author's own collection.

1895 Cleveland and South Durham Baseball Association runner-up medal fob (?), Tom Cotton, Middlesbrough Baseball Club. Author's own collection.

Harrison Supply Company, Nathan C Harrison, treasurer, letter 1917. Author's own collection.

Harrison Supply Company, Nathan C Harrison, treasurer, letter 1917. Author's own collection.