Slugger

Jamie Barras

The big question about Hidezo ‘H’ Nishikawa’s two blazing seasons as a pitcher in the London leagues (1937 and 1938)[1] is, why did the leagues give this total unknown—and total outsider—a tryout in the first place? Elsewhere,[2] I’ve speculated that it was because, by 1937, baseball promoters in London already had cause to respect the abilities of Japanese baseball players thanks to visits to the capital by Japanese teams in the late 1920s and early 1930s. However, here, I want to explore the possibility that it was something much simpler and more direct: at Romford, where Nishikawa played his baseball, there was a player and coach with firsthand knowledge of just how good Japanese-born players could be. His name was Merrick ‘Slugger’ Cranstoun.

One man stood between Durex and victory—Merrick Cranstoun, the Earl’s Court Ranger ice hockey “star”. His pitching had the Durex men in two minds. It swerved deceptively and proved unplayable.[3]

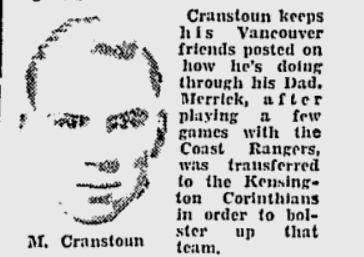

Plomer Merrick Cranstoun (1911–1976) was an Ontarian by birth. ‘Merrick’ was his mother’s maiden name, inherited from a famous ancestor, William Merrick, namesake of Merrickville, Ontario, the village where Merrick, as he preferred to be called, and his older brother Jack Jr (John Merrick Cranstoun, 1907–1988) were born. By the time Merrick had turned five, his grocery clerk father, Jack Sr., had moved the family west to Rouleau, Saskatchewan. There, the family grew in size with the addition of two more children, Marion (b. 1918) and Gerry (b. 1921). In 1923, Jack Sr.’s grocery store went bust, and he moved the family to Regina, the provincial capital. Then, in 1928, they set off west again, fetching up in Vancouver, British Columbia, where Jack Sr. found work as a chain store manager. By 1931, Merrick was working as a bookkeeper at a stevedoring company, while big brother Jack Jr was an accountant at a bank.[4]

However, the first love of both brothers was team sports. Merrick had gotten his start in team sports early, turning out for the Moose Jaw Maroons ice hockey team at age 17. But it was Jack Jr who was the real star. By 1926, aged 19, he was a regular in the line-up of the Regina Pats ice hockey team, and was even scouted by pro team Detroit (he declined the offer). He also played American football and Canadian rugby. That same year, he was instrumental in the formation of a junior baseball league in Regina, turning out for the Regina Argonauts. (That summer, the Argos embarked on a mini national tour to gain some experience playing established teams. In Winnipeg, Manitoba, they played local junior team West End. The Enders’ star pitcher was Sid Bissett, future star of baseball in the British Midlands and relief pitcher for the 1938 Great Britain team. Merrick Cranstoun would have his own encounter on the diamond with Sid Bissett in 1936—see below.) Once in Vancouver, he turned out for the Vancouver Ex-King George ice hockey team in the amateur Vancouver City Senior League (where, by 1932, Merrick had joined him). He also began his adult baseball career, joining the Generals, who played in the amateur Vancouver Terminal League.[5]

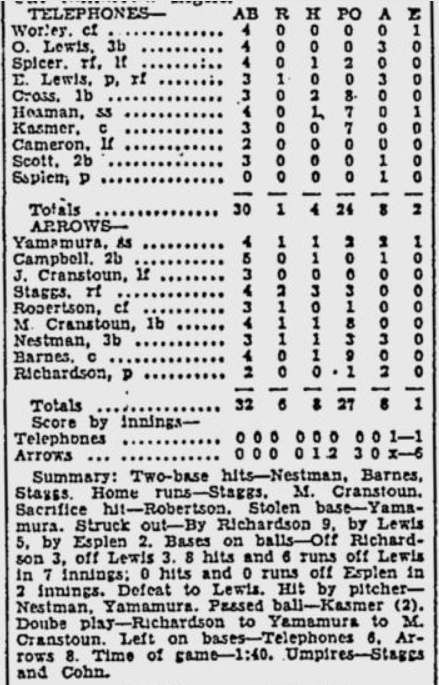

However, for our purposes, of more immediate significance is that, in 1930, Jack Jr joined the Arrow Transfer (aka Vancouver Arrows) baseball team (Arrow Transfer was—and still is—a BC-based trucking company[6]), which played in the amateur Vancouver Senior City League. This is of particular significance to our story as, the following year, Merrick joined him on the roster as an outfielder and first baseman.[7]

The Arrows pounded the horsehide for 19 base blows as they annexed their initial victory of the season, a 20 to 5 scalping of the V.A.C. aggregation. The game was essentially over after the Transfermen tallied ten runs in the first crack at bat. Every one of the Arrow regulars produced at least one safety with Merrick Cranstoun, Fred Condon and Andy Padovan showing up best with the stick, drilling three hits apiece.[8]

The topic of amateur baseball in British Columbia in the interwar years is a vast one, and I will not even attempt to cover even a fraction of it here. Readers are recommended to consult the Western Canada Baseball website, curated by Jay-Dell Mah, for a comprehensive overview of the scene.[9] I draw much of the following from there.

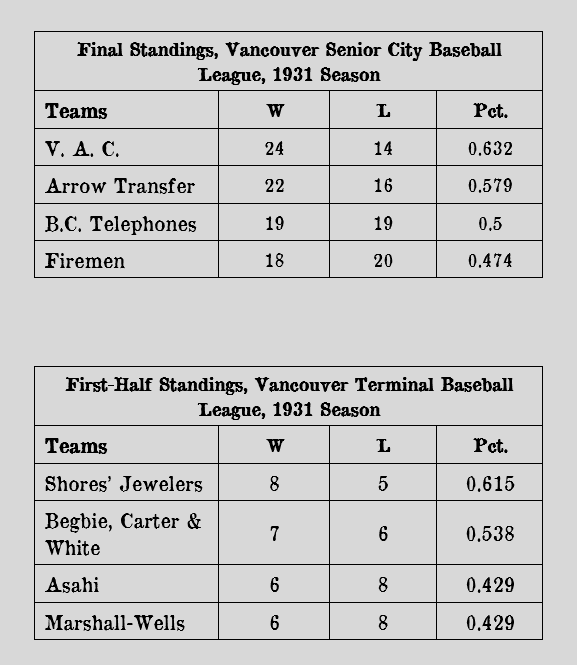

By 1931, the year that Merrick Cranstoun joined his brother Jack Jr in the Arrows, there were two main amateur leagues in the city, each with four teams, the Vancouver Terminal League and the Vancouver Senior City League, with the latter being the tougher of the two in terms of the level of competition.

In 1931, the Senior City League comprised the Vancouver Athletic Club (V.A.C.), Arrow Transfer (Arrows), B.C. Telephone, and the Firemen; while, in the Terminal League, there were Shores’ Jewellers, Begbie, Carter & Wells, Asahi, and Marshall-Wells. See the league tables in the gallery at the end of this article, reproduced from the Western Canada Baseball website.[10]

The Terminal League line-up is of particular interest to us here, as, as can be seen from the list and table, it consisted of three teams associated with/sponsored by businesses, Shores’ Jewelers, the Begbie, Carter & White Auto Dealership, and Marshall-Wells Department Store (although the baseball team of the latter may have been associated with the company warehouse rather than the store), and a fourth, the Asahi.

The latter is the now-famous [Vancouver] Asahi team of Japanese-Canadian baseballers, which won a dozen championships across British Columbia from its inception in 1914 until its disbandment in 1942 at the outset of the Pacific War. It has since been the subject of several books, at least one documentary, and a movie. It was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame as a team in 2003.[11]

The Asahi first played in the Terminal League in 1921, the beginning of a five-year run that culminated in 1926 with them winning the league with their patented ‘brain ball’ style of play (an infield game that used bunts and steals to offset the Asahi players’ lack of hitting power). They made the step up into the Senior City League the following season. However, that proved to be a mistake, as the Senior players were just that bit sharper, just that bit less likely to make errors or be slow in fielding the ball. After three seasons finishing bottom of the league every time, the Asahi returned to the Terminal League and their winning ways in 1930.

(Coincidentally, 1921, Asahi’s first year in the Terminal League, was also the year that they toured Japan. The tour included three games in the Kobe area—where Nishikawa was born and raised—including one against a team that Nishikawa would later play for, the Star Club (スター倶楽部). Nishikawa would have been 12 years old at the time and a budding schoolboy baseball player. It is nice to think that he saw at least one of the games.)

From the above description alone, it can already be seen that Merrick Cranstoun had every reason to be very familiar with the quality of baseballers of Japanese heritage just based in his participation in the 1930s Vancouver amateur baseball scene; however, in 1931, his first season with the Arrows, he got to see it at close quarters, because that year, one of the mainstays of the Asahi team defected to the Transfer team and played half a season alongside the Cranstoun brothers.

Up until the ninth stanza, the Transfermen led only by a single tally, compliments of Pete Staggs’ second-frame solo homer but things fell apart for the Phones in that fateful last panel. Jack Cranstoun, Roy Yamamura, Graham Robertson and Johnny Nestman each banged out two base blows for the Arrows with a triple being part of Cranstoun’s total.[12]

Roy Yamamura (ロイ・ヤマムラ, 1907–1990) was Asahi’s star shortstop. A master of ‘brain ball’ and base-stealer extraordinaire, he would spend over 30 years as a player and manager in teams in first, Western Canada, and then, following the Second World War, Ontario and Quebec semi-pro leagues. He was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 2021.[13]

The problem from Yamamura’s point of view with the 1931 season was that Asahi were in a slump. After dominating the Terminal League in their first stint, 1921–1926, and then coming back and winning it all over again in 1930, by midway through the 1931 season, they were tieing Marshall-Field for last place. This was not how it was supposed to be. After a tied game with the touring 1930 Japanese high school baseball champions, Hiroshima Commercial High School (広島商業高等学校, Hiroshima shōgyō kōtō gakkō), on 21 July and a 12–1 drubbing by Shores’ Jewelers on 22 July, Yamamura had had enough: two days later, he debuted for the Arrows, playing out the rest of the season and the semi-final playoffs with them.

Yamamura returned to the Asahi for their 1932 season, and the Asahi returned to their winning ways, bagging the Terminal League Championship in both 1932 and 1933.[14] He would go on to be a key player in the Vancouver amateur teams’ 1935 campaign against the touring Greater Japan Tokyo Baseball Club (大日本東京野球倶楽部, Dai-Nippon Tōkyō Yakyū Kurabu), which would go on to become the Tokyo Giants, Japan’s first professional baseball team of the ‘pro baseball’ (プロ野球) era (there had been at least two earlier professional teams in Japan in the 1920s, but they played largely exhibition matches for promotional purposes). Yamamura was in the Vancouver All-Stars side that handed Dai-Nippon their one defeat of the Western Canada leg of their tour.[15]

Yamamura captained and managed the Asahi for the final four years of its existence (1937–1941 seasons). Like many of his teammates and thousands of other Japanese-Canadians, he was interned at the outset of the Pacific War, and, following the end of the war, left behind the prejudice he had experienced on the west coast and moved to Canada’s eastern provinces.[16]

Merrick Cranstoun gained first-hand experience of how good players of Japanese heritage could be that half season in 1931, playing alongside Roy Yamamura. He may also have witnessed Dai-Nippon cut a swathe through Vancouver’s best amateur teams in 1935, giving him experience of watching players who had learned their game in Japan play. However, for reasons we will see below, whether he saw those latter games or not, he himself would not play baseball in Vancouver in the summer of 1935. As an aside, there was at least one other BC player in the English leagues who had played against both the Asahis and Dai-Nippon and had played alongside a Japanese-Canadian player. This was Leo ‘Doc’ Holden, who played against the Asahis and Dai-Nippon in the Sons of Canada, Victoria, BC, and had played alongside ‘Sheiky’ Ashikawa, formerly of the Taiyos, in the Camerons in the Victoria Senior Amateur League. Holden played all his baseball in England in Yorkshire. [17]

Merrick Cranstoun’s ninth-inning smash through second, his second hit of the contest, drove in the winner as the Arrows edged the Telephones 7 to 6 in a walkoff thriller. Pete Staggs had led off the frame with a single and was ably sacrificed to the keystone sack by Arne Miller before Cranstoun’s game-winning hit.[17]

Both Cranstoun brothers again turned out for the Arrows in the 1932 Senior City League season (while also remaining active in ice hockey in the close season [or vice versa]). The Arrows topped the table at the end of the season, but lost out to V.A.C. in the playoffs. Only Merrick Cranstoun would return to the Arrows roster for the 1933 season (Jack Jr left Vancouver and moved back east, pursuing his career in banking; by 1947, he was managing the Moose Jaw branch of the Bank of Nova Scotia; he appears to have abandoned team sports by 1935). In a repeat of the previous season’s results, the Arrows topped the table but lost the playoffs. The following season, Merrick Cranstoun’s last with the Arrows, the Transfer team slumped to third in the league but had a good run in the playoffs before, ultimately, losing the finals to one of the two teams new to the Senior League that season, Arnold & Quigley (which had a long history in some of the city’s other leagues; A&Q was a men’s clothing store). Late in 1934, under murky circumstances, the British Columbia Amateur Athletic Union refused to issue Merrick and two other Senior League players, Frank Hall (V.A.C.) and Billy Adshead (Arrows), amateur cards after reports that they had received payment for playing in the league. As the ruling covered ice hockey too, Merrick Cranstoun was effectively shut out of sport in Vancouver. So, Cranstoun struck a deal: as the offence was in connection with baseball, he agreed not to play any more ball as long as he could have his amateur card back to play ice hockey. In the event, by the summer, he was playing with the idea of breaking the deal, signing with new team in the Terminal League, Lowney’s Chocolate; however, ultimately, he did not take the field (he did play at least one game of softball with the Castles team, but this may have been to test the waters). If he was going to continue playing baseball, he would need to look for somewhere else to play.[18]

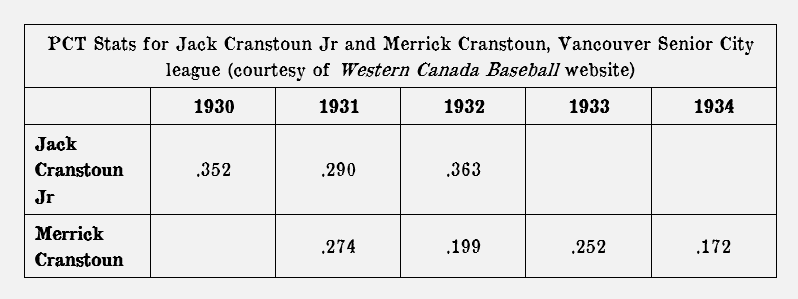

The first stage of Merrick Cranstoun’s baseball career was over. As the PCT stats, taken from the Western Canada Baseball website, in the gallery at the end of the article show, of the two Cranstoun brothers, it was big brother Jack Jr who was by far the bigger hitter at this stage in their lives.

Truth be told, Merrick Cranstoun would only come into his own as a baseball player after his move to England. And that move only came about because of his skills as an ice hockey player.

TO-NIGHT’S ICE HOCKEY Earl’s Court Rangers Visit Wembley Canadians. Merrick Cranstoun, a centre-forward from Vancouver, British Columbia, turns out for Earl’s Court Rangers in their London — Paris Tournament match against Wembley Canadians at Wembley to-night. Cranstoun, who has splendid puck control, partners Chappell and Peterson in the first forward line.[19]

The 1935–1936 ice hockey season in England was the inaugural year of the English National League (ENL), a new development in ice hockey in England that saw the axis of the sport shift decisively away from purely amateur university clubs under the auspices of the British Ice Hockey Association (BIHA) toward de facto professional teams owned by venues, particularly venues in and around London, under the control of the English Ice Hockey Union, the ice rink managers’ official body.[20] Chief amongst those venues was undoubtedly Wembley Arena, which had begun its involvement in ice hockey the previous year in the BIHA league and hosted two teams, the Wembley Lions and Wembley Canadians. New for the inaugural ENL season was the involvement of the Empress Hall venue at Earl’s Court, which had begun life as the Empress Theatre and could seat 7000. In 1935–1936, the Empress Hall would host two teams, the Earl’s Court Rangers and the Kensington Corinthians.[21]

The key figure in this venue-based league, however, would be Canadian Percy Nicklin (1893—1973), who was brought to England in 1935 to coach the Richmond Hawks and went on to coach the Harringay Racers and Harringay Hawks in future seasons. It was Nicklin who assembled and coached the Great Britain Ice Hockey Team that won gold at the 1936 Winter Olympics and then dominated the European Ice Hockey Championships for the next two years. He was inducted into the British Ice Hockey Hall of Fame in 1998.[22]

Nicklin’s recruitment provides a clue as to how the ENL managed to establish itself so quickly: coaches like Nicklin simply opened up their address books (and their team-owners’ cheque books) and started calling the players they had coached back in Canada, an approach that would lead to the ENL being accused of ‘shamateurism’, a cardinal sin in the eyes of the great and the good of the English sporting world. It would also lead to complaints of poaching from Canadian team owners.[23]

Regardless, in the autumn of 1935, Canadian players started arriving in England by the shipload: Eleven of the players that would fill out the rosters of the Earl’s Court Rangers and Kensington Corinthians arrived in England on board a single ship, the SS Montcalm, on 13 October 1935. A month later, the SS Berengaria docked at Southampton, and Merrick Cranstoun set foot in England for the first time.[24]

Cranstoun would play his first game for the Earl’s Court Rangers, but spend most of the season playing for the other Earl’s Court team, the Kensington Corinthians, which was his bad luck, as the Corinthians had a disastrous season, finishing bottom of the league and folding at the end of the season. Cranstoun may have been looking forward to a second shot at playing for the Rangers, but instead, in early 1936, he found himself added to the roster of the Corinthians’ replacement, the Earl’s Court Royals.

He also found himself back playing baseball.

GEE! THEY’RE GOING TO PUT BASEBALL OVER BIG. Hearing that several Earl’s Court ice-hockey players had signed for Romford Wasps baseball team, our correspondent, Albert Male, has been to interview them to obtain their views on prospects for the coming baseball season.[25]

The story of Liverpool sports betting magnate John Moores’ attempts to relaunch American baseball in England in the 1930s has been covered at length by several authors.[26] In brief, John Moores (1896–1993) was introduced to baseball through his involvement in a version of the game known as ‘English Baseball’, derived from rounders, that was popular in Liverpool and South Wales from the 1880s until the advent of the Second World War (and which would continue to be played at a smaller scale down to the present).[27]

In 1932, Moores became the patron of a breakaway group of Liverpool-based teams within English Baseball that called itself the English Baseball Union. The following year, he went to America and, perhaps, thanks to a chance meeting with National League president John Heydler in a New York hotel room, got to experience baseball American-style for the first time (which is to say, the game played by highly skilled professional players in front of crowds of tens of thousands; he may have already seen games played under the American code in England but played by amateurs). He returned to England convinced that this was the way ahead. He attempted to persuade the Liverpool adherents to the English code to switch, an attempt that largely failed.[28]

Undeterred, Moores devoted his considerable financial resources to launching a national baseball association to promote the American code. He started his missionary work in North-West England, launching leagues there in 1934, but an early convert was Moores’ friend, London-based American businessman, Leonard D. Wood. It was Wood who was the driving force behind getting amateur leagues established in the capital for the 1935 season, and a ‘professional’ league, the London Major Baseball League (LMBL), launched the following year. Wood would himself start a team, West Ham, operating out of the speedway and greyhound racing stadium at Custom House in East London. The team was centred on a raft of Quebecois players led by British Baseball Hall of Famer Roland Gladu (1911–1994) and featuring future ace hurler of the LMBL, Gerald Keith ‘Jerry’ Strong (1913–1958), who was credited in contemporary newspapers as being the first pitcher in England to pitch a ‘no-hitter, no-runs’ game (disputed). Among the non-Quebecois players in the 1936 West Ham team was Jake ‘Poison’ Asbell (1910–1995), a Saskatchewan native of Russian Jewish extraction who learned his baseball playing for the 1931 Saskatchewan Junior champions, the Viceroy Twin Vees, and had been in the UK since 1934.[29]

The other teams in the LMBL in its inaugural year were White City, Streatham & Mitcham Giants (briefly[30]), Harringay, Catford Saints, Hackney Royals, and Romford Wasps.[31]

Cheetahs Race on Track Beat Greyhounds CHEETAHS, claimed to be the fastest animals in the world, raced last night for the first time on a greyhound track. They streaked round Romford Stadium at a pace which made the greyhounds seem slow. Miss Ruby Henderson, their trainer, looked on.[32]

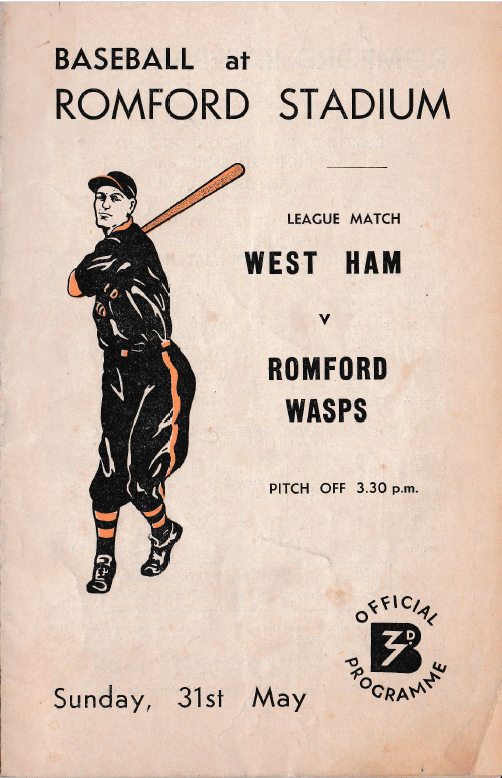

The man behind Romford’s move into American baseball was Archer Leggett (1900–1989), the go-getting owner of Romford [greyhound] Stadium. Leggett had a showman’s eye for spectacle, and it is possible that he viewed baseball on a par with cheetah racing: simply as something exotic to bring in the punters. That said, he did invest heavily in baseball, and the first team to be based at the stadium, Romford Wasps, would be the longest-lasting of the teams in the LMBL (although a good measure of the credit for that should go to the Romford faithful).[33]

The two other Earl’s Court ice hockey players recruited alongside Cranstoun to join the Wasps were Paul ‘Scotty’ McPhail (1915–1982) and Howard ‘Howie’ Peterson (1913–?).[34] McPhail was born in Scotland, but his father moved the family to Canada when Paul was only 3. McPhail Sr. took up gold mining, and young Paul followed him into the trade. He learned his ice hockey in Quebec before traveling to England on the SS Montcalm with 10 other players. In 1937, thanks to his British birth, he was able to turn out for the World Silver Medal-winning Great Britain Hockey Team. Howie Peterson was another of the Montcalm passengers and learned his ice hockey in his home province of Ontario before his England move.[35]

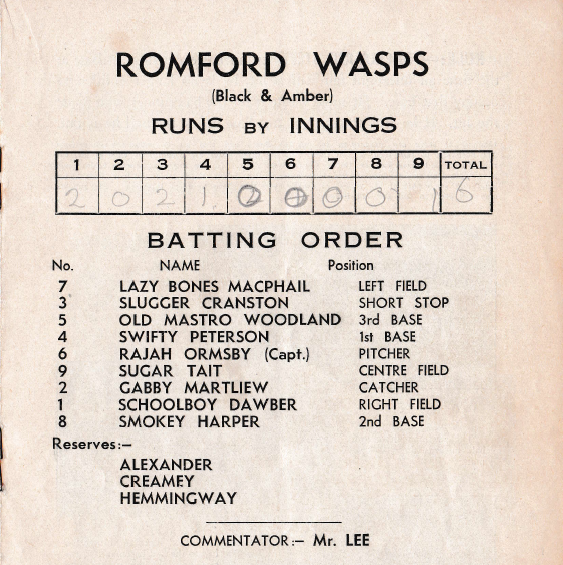

Joining the three ice hockey players in the Wasps for the 1936 season were Art Ormsby (capt.), Fred Martilew—an employee of the Ford factory at Dagenham, Essex, which was itself home to a baseball team (Ford Sports)—Glen Allan, G. Tait, local boy Les Woodland, H. Lumb, and H. Harper.[36] Rounding out the team was British Baseball Hall of Famer, Bill Dawber (1921–1983), just fifteen at the time. Someone—almost certainly Leggett—issued the players with nicknames, which is how Dawber became known as ‘Schoolboy’, McPhail as ‘Lazy Bones’, Peterson as ‘Swifty’, and Cranstoun as ‘Slugger’.[37]

Their coach was Roger Evans. It is not clear if this is the same Roger Evans who had previously been an umpire and coach for the Streatham amateur team, and who, in April of the following year, was charged with stealing £8 from a woman. At his trial, this Roger Evans, who was described as a ‘baseball player”, and formerly an umpire, was revealed to be a Welshman raised in Canada who had had a string of convictions for larceny in the US and Canada, and had been deported to the UK in 1934 following his escape from a US prison and subsequent recapture. This Roger Evans was also said to have been unemployed since September 1936, which would be consistent with him being let go at the end of the 1936 LMBL season, which is what would happen to the Roger Evans who was the Romford Wasps coach. A strange affair.

“SLUGGER” CRANSTOUN pitched Romford " Wasps" to victory when they defeated Catford Saints by 6 runs to 2 in the London Major League yesterday. His pitching was the feature of the day, for he fanned eleven batters by the seventh innings, when rain stopped play.[38]

Cranstoun’s first season as a Wasp was the making of him as a baseball player. He came into his own as a big hitter—including scoring two home runs in one game[39]—but, more particularly, turned out to be a fearsome, if erratic, hurler. His crowning achievement that first season was a shut-out against a Birmingham amateur team, Durex Abrasives, in the second round of the NBA Challenge Cup. Durex had defeated West Ham in the first round, thanks in no small part to their pitcher, another Canadian ice hockey player, Donald Alexander ‘Sid’ Bissett (1905—1992), who learned his baseball in Winnipeg, but there was nothing they could do against the in-form Cranstoun.[40] (The first week of August 1936 was a banner week for Cranstoun: as well as shutting-out Durex, he married his hometown sweetheart, Renee Rushton, who had travelled the 4800 miles from Vancouver for the event.[41])

Cranstoun was also the pitcher when West Ham star Roland Gladu hit an ‘infield fly’[42] with the bases loaded, which, as per the rules, but to the complete puzzlement of the unknowledgeable London crowd, resulted in the umpire calling Gladu out despite no fielder catching the ball. As early as 8 May, ‘Homer’, the baseball correspondent for the West Ham and South Essex Mail (who may have been a West Ham player), had pointed out that this sort of confusion would become a problem for the league as long as the league did nothing to educate fans on the rules.[43]

However, Cranstoun also had his off days, something that was not helped by Wasps coach Evans’ tendency to switch out pitchers almost on a whim.[44] Wasps’ problems went much deeper than Cranstoun’s lack of consistency, however; they were notoriously bad at fielding, something that they (Evans) seemed incapable of rectifying. They lost 8–1 to the Oldham Greyhounds in the quarter-finals of the Challenge Cup, and ended the 1936 LMBL season at the bottom of the table, having won only 3 of their 20 games. In the course of their league campaign, they had conceded 224 runs, 61 runs more than the next-worst-performing team.[45]

Archer Leggert could not have been pleased with how his investment was going, but, to his credit, he decided to continue to back the team. However, he knew that changes needed to be made: out went Roger Evans as coach. Leggett didn’t have to look far for a replacement, however. Aged just 26, Cranstoun would start the 1937 LMBL season as both player and coach of the Romford Wasps.[46]

RANGERS ROUT THE ROYALS Ice Hockey League Games Last Night Earl's Court Rangers defeated their co-tenants, Earl's Court Royals, in a National League match at the Empress Stadium last evening. In a game of missed chances, Rangers, with only a few new faces, as against their newly formed rivals, won because of their superior combination and understanding.[47]

By the Spring of 1937, Cranstoun may well have felt that he just could not catch a break in England. After propping up the English National Ice Hockey League with the Kensington Corinthians and the London Major Baseball League with the Romford Wasps, he found himself propping up the English National Ice Hockey League a second time in the 1936–1937 season with the Corinthians’ replacement at Earl’s Court, the Earl’s Court Royals. However, things were about to change. Empowered by Leggett to reshape the Wasps the way he wanted them, he set about recruiting new players and doubling down on training.

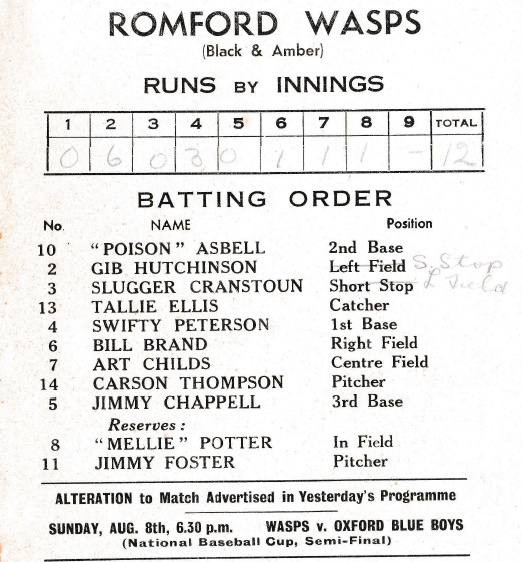

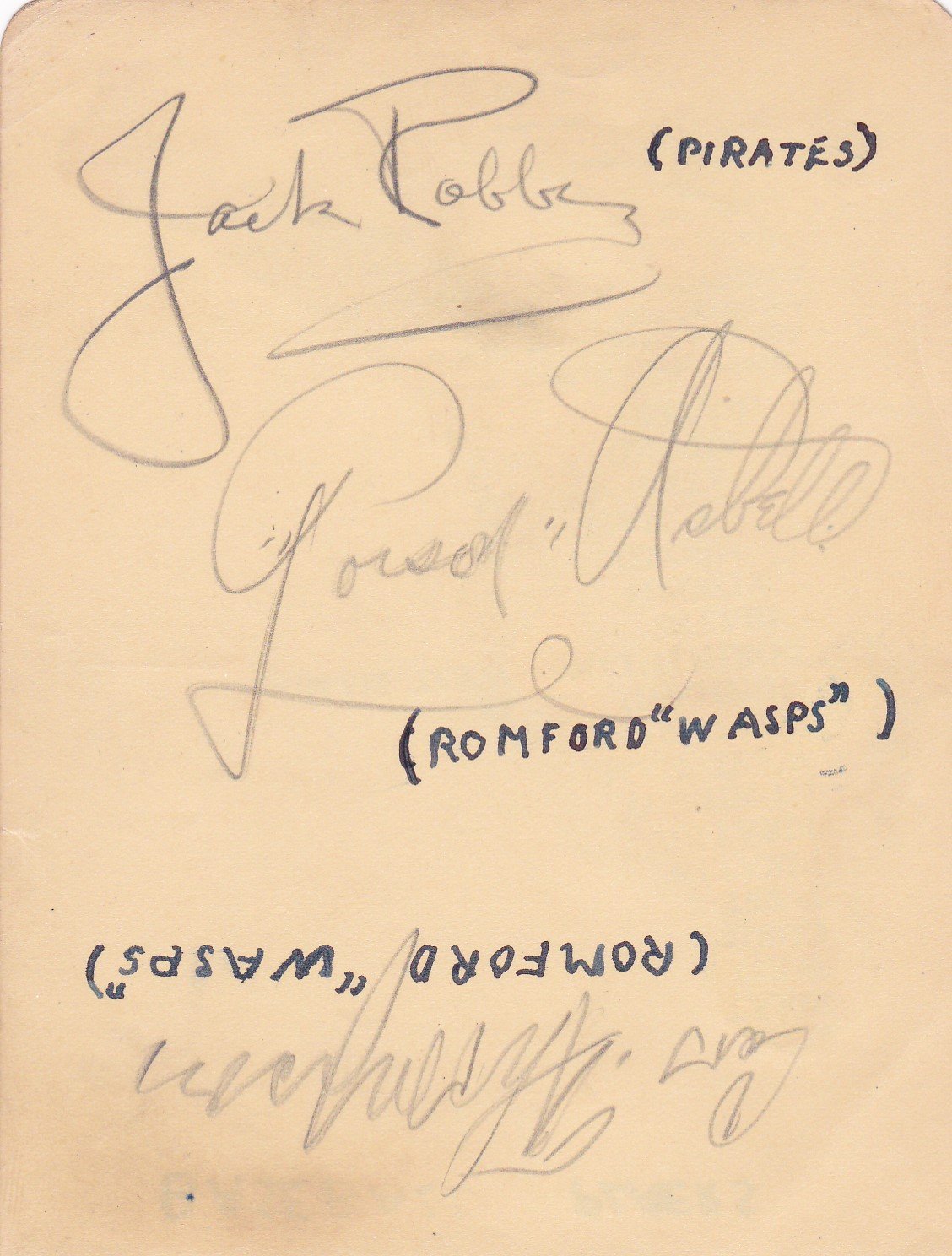

One of his recruits was Jake ‘Poison’ Asbell, the Saskatchewan native of Russian Jewish heritage who had played the 1936 season for West Ham. Joining Asbell in the new Wasps was a raft of ice hockey players, including four future British Ice Hockey Hall of Famers, three of them members of the 1936 Olympic-gold-medal winning Great Britain team: Jimmy Foster (1905–1969), the superbly skilled goalkeeper for first the Richmond Hawks and then the Harringay Greyhounds—probably Percy Nicklin’s best signing; Art Child (1915–1996), relief goalkeeper for the Earl’s Court Rangers in 1936–1937; and, another Rangers player, centre Jimmy Chappell (1915–1973). The fourth future BIHHoFer that Cranstoun recruited was Rangers goalkeeper Gib Hutchinson (1912–1996), who was going through a slump on the rink at the time.[48] As catcher, Cranstoun brought in Floridan minor-leaguer Tallie DeWitt Ellis (1914–1976), one of at least six players from the Sunshine State in the LMBL that year.[49] ‘Schoolboy’ Bill Dawber, meanwhile, had dropped down to the amateur leagues, beginning what would be a long career playing for company teams (Pritchett & Gold in 1937) that would culminate in him leading Thames Board Mills to back-to-back national championships in 1959 and 1960.[50]

The 1937 LMBL season was the season when everything went right for Cranstoun. Romford were no longer deficient in fielding—they conceded almost half the runs they did the previous season[51]—and Cranstoun had found his rhythm as a big hitter. He was also excelling as a pitcher, although he could still be alarmingly erratic, and rarely pitched a full game. Still, it is fair to describe the 1937 LMBL season as a three-way hurling contest between Cranstoun, West Ham’s Jerry Strong, and new team—and stablemates of the Wasps at Romford—Corinthians’ Hidezo ‘H’ Nishikawa.

NISHIKAWA PITCHES CORINTHIANS TO VICTORY […] Nishikawa pitched the entire game for the visitors and, with the exception of the last two innings, had the Saints completely under control. Many times they managed to get men on bases only to have them die there, successive batsmen being put out by the Japanese star.[52]

I have written extensively about Hidezo ‘H’ Nishikawa’s life and career elsewhere.[53] In brief, Hidezo Nishikawa (西川英三, Nishikawa Hidezo, 1909–1988) was a Kobe University graduate known only in the contemporary British press as ‘H. Nishikawa’, or by his appalling-to-modern-ears nickname ‘Nip Nishikawa’. The same British press described Nishikawa as a ‘Japanese International’ and the assumption then and since was that he had been somehow recruited specially to come to London to play baseball. However, thanks to colleagues in Japan, I was able to establish that H. Nishikawa was Hidezo Nishikawa, who had travelled to England in the Spring of 1937, not to play baseball, but to visit his older brother Koichi, who had, by that time, been living in Britain for nearly a decade and had married an Englishwoman. For complicated family reasons, Hidezo’s stay extended to nearly three years. Rather than being a ‘Japanese International’, he was a good semi-pro player with a raft of appearances in the High School Baseball Championship (Koshien), two appearances in the All-Japan Intercity Championship, and who had turned out in at least one game against visiting American opposition, probably the ‘Negro Leagues’ team, the Philidelphia Royal Giants.

Nishikawa was an ace hurler, arguably the second-best in the 1937 LMBL, who changed the course of the season of the first team he joined, the Corinthians, stablemates of the Romford Wasps in the 1937 season, and pitched the Wasps to victory in the 1938 London Senior Baseball League season. As stated at the beginning of this piece, with the revealing of the real Nishikawa story, the question became how, if he wasn’t recruited especially, the LMBL came to give him a tryout. We know that Nishikawa didn’t make an approach until at least three weeks into the season (his recruitment was reported four weeks into the season[54]) by which time rosters had been set. Although it can be supposed that the league would always find space for a quality player, the question remains why they would even consider that this young East Asian man was worth looking at.

I have pointed out that Japanese baseball teams, and indeed, individual players on rare occasions, had played one-off games in London and elsewhere in England in the late 1920s and early 1930s (they were a feature of Moores’ efforts to establish the American code in Liverpool, for example[55]). So, there were indisputably people in England who had reason to appreciate what Japanese players could bring to the diamond. That does not, of course, place any of those people in Romford in late May 1937, when Nishikawa made his approach. However, equally indisputably, as I have shown in this current article, there was someone at Romford who had direct knowledge of what baseballers of Japanese heritage could bring to the diamond: Merrick Cranstoun, witness to the rise of the Vancouver Asahi and teammate of Asahi star Roy Yamamura.

But how likely is it that Cranstoun had any role in Nishikawa receiving a tryout?—after all, he certainly didn’t recruit Nishikawa into the Romford Wasps. To answer that question, we need to look at the situation at Romford between the Wasps and new team, Corinthians.

BASEBALL HAS ITS CORINTHIANS NOW THEY'LL soon be hitting " homers " again. The London Major Baseball League opens its season on May 1, and everything is now ready for the big pitch-off. Newcomers to the League are the Corinthians, who are to play mostly away games.[56]

Early announcements around the formation of the Corinthians suggested that they came into being through a simple desire by the LMBL to make up the numbers after the folding of no less than three of the six 1936 LMBL season teams in the close season: Harringay, White City, and Hackney Royals. Most of the White City team relocated to Nunhead, adopting that as their new name. The returning Catford Saints joined Nunhead in playing their games at the ground of Nunhead F.C. Meanwhile, at West Ham, L.D. Wood doubled down in his investment in American baseball in London by launching the Pirates, stablemates of the returning West Ham team at the Custom House stadium.[57]

That left one slot vacant, and the LMBL conjured up the Corinthians to fill it. By late April, the British press was reporting that two of Tallie Ellis’s fellow Floridans, Walt Stevens and Doyle McNeece, had been picked to coach the Corinthians, who were now to be based at Nunhead.[58] However, ultimately, it was Romford where Corinthians would find a home.

At Romford, Archer Leggett set about putting his mark on his new acquisition, ladling out nicknames (‘Mack’ McNeece, ‘Wally’ Stevens, ‘Bunt’ Roberts, ‘Doc’ Sirota, ‘Lefty Galbraith[59]). However, the team got off to a disastrous start, going 0–4 in its first four outings.[60]

And then Nishikawa turned up at Romford Stadium. He started pitching for the Corinthians in his second week in the team, and within six weeks had taken them from the bottom to the top of the league—knocking stablemate the Wasps off the top spot.[61] At which point, someone (Stevens? McNeece? Leggett?) pulled him from the mound, and Corinthians slumped back to third, which is where they finished the season. Nishikawa’s absence from the mound late in the season was almost certainly because of injury or fatigue, but it is interesting to note that this left the way clear for Corinthians’ stablemates, the Wasps, to scoop up enough points to beat West Ham to the title. While there is no evidence that I know of to suggest that Leggett issued ‘team orders’, it has to be acknowledged that having two Romford-based teams actively competing with each other for the title carried the risk that they would cancel each other out, allowing their West Ham rivals to sneak the title. Nishikawa’s absence from the mound—again, almost certainly due to injury or fatigue—eliminated that risk.

All of which returns us to the question: who influenced the Corinthians’ decision to give Nishikawa a tryout? Although ultimately, it would have been Stevens and McNeece’s call, Merrick Cranstoun was right there at hand to provide the benefit of his experience with players of Japanese heritage back in BC. There is even reason to believe that Cranstoun was head coach at Romford, overseeing the Corinthians while Stevens and McNeece ran the team day-to-day (this was the situation at West Ham, where Roland Gladu was head coach for West Ham and the Pirates, with another of the Florida players Eddie Mumma running the Pirates day-to-day[62]). Added to this, it would certainly have been consistent with Leggett’s decisions to date for him to have seen Corinthians propping up the bottom of the table one month into the new season, and asked Cranstoun to step in and work his wonders on the failing team the way he had the Wasps.

Of course, it has to be acknowledged that there is a risk of becoming carried away with the idea of linking a forgotten Japanese player in the London leagues with the world-famous Vancouver Asahi—everything is not connected. However, at the same time, it is undeniable that Cranstoun had means, motive, and opportunity.

Wasps Are Baseball Champions WOODEN-SPOONISTS last season, Romford Wasps, at West Ham Stadium last night, won the London Major Baseball League championship with a ten runs to six victory over Pirates. West Ham, whose match with the Wasps at Rumford Stadium on Sunday evening winds up the London Major League season, are runners-up for the second consecutive year.[63]

With Nishikawa no longer pitching for Corinthians, the way was clear for the Wasps to take the 1937 LMBL title, cementing a remarkable turnaround made possible by Merrick Cranstoun’s leadership and now-mature skills with bat and ball. Cranstoun also took the team to the final of the NBA Challenge Cup, where their opponents were Hull. The Wasps lost 5–1 thanks primarily to a dazzling performance by Hull’s pitcher, British Baseball Hall of Famer Max ‘Lefty’ Wilson (1916–1977), who had started the season with Catford Saints before being moved to Hull midseason. Cranstoun acknowledged Wilson’s dominant role in his concession speech.[64]

Alas, 1937 marked the end of the road for the London Major Baseball League, which had never achieved the attendance levels it needed to be viable. With bitter irony, one of the contributing factors was the effectiveness of pitchers like Strong, Nishikawa, and Cranstoun on the mound—British sports fans, raised on cricket, were just too used to seeing high-scoring games with long periods of uninterrupted play, something not possible with the American code, with its strong batteries, sharp fielding, and three-outs-all-out rule (not coincidentally, the chief differences between the American and the English code were the absence of these elements from the English game).[65]

American baseball in London would continue at an amateur level, as, indeed, would the Romford Wasps (with Nishikawa as their pitcher for their 1938 league-winning season), until the advent of the Second World War. However, for Cranstoun, it was time to move on.

At Harringay, the Racers defeated Brighton Tigers in the London Cup tournament. Creighton and Peer each netted twice for the winners, for whom Monson and Nicholson Mao scored, while Gibson and Cranstoun went through for the visitors.[66]

Cranstoun left Earl’s Court for Brighton for the 1937–1938 ENL season. Elsewhere, Moores’ National Baseball Association (NBA) made changes in response to the collapse of the LMBL. Unable (or at least, unwilling) to change the rules to suit English sports fans’ inability to warm to strong batteries and low scores, the NBA introduced a quota on foreign or professional players (effectively the same thing), placing the limit at no more than two per team. This had the effect of putting a raft of the best players in the NBA leagues out of a [summer] job. Their solution to this was to set up a rival International Baseball League (IBL, aka International Professional Baseball League, IPBL) in June 1938, with teams across the North of England. Cranstoun, one of the players affected by the introduction of the quota, turned out for Newcastle in the IBL for at least one game. However, the IBL never attracted much interest from [confused] British sports fans and folded after only one month. Coincidentally (or not), Nishikawa also played a single game in the IBL while continuing to turn out for Romford Wasps.[67]

The 1938–1939 ice hockey season would see Cranstoun move north of the border to turn out for the Dundee Tigers.[68] He would also turn out for Hull in the NBA’s Lancashire–Yorkshire Major League in the second half of the 1939 season. However, Cranstoun’s old demon, his last of consistency, came into play once more, with him walking no fewer than 12 Halifax players in a match in July, resulting in Hull’s defeat and exit from the Challenge Cup, which they had won for the past two years. Halifax also topped the league that year, cementing 1939 as Hull’s worst year in the NBA to date.[69]

At this point, the Second World War intervened, putting an end to John Moores’ attempts to introduce professional American baseball leagues in England, which, truth be told, was a mercy killing. Games under the American code would resume at the amateur level after the war, with Hull one of the centres of the game.

The 1939–1940 ice hockey season in Scotland, although a necessarily muted affair, went ahead, and Cranstoun turned out again for the Dundee Tigers.[70] However, the end of the season marked the end of his time in the UK. On 25 May 1940, he and his wife, Renee, boarded the SS Duchess of Bedford and set sail for home.[71]

Once back in BC, Cranstoun would continue his involvement in ice hockey, joining the New Westminster Spitfires for their 1941 season. By 1952, he was officiating games in Saskatchewan.[72]

He died in BC in 1976.

Jamie Barras, July 2025

Back to Diamond Lives

Notes

[1] I tell the story of those two seasons here: Jamie Barras, ‘Tracing an Enigma: H Nishikawa, Ace Pitcher of 1930s English Baseball’, Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, 2026, forthcoming.

[2] See Note 1 above.

[3] ‘Great Pitching’, Evening Dispatch, 3 August 1936.

[4] This information can be assembled from census records for John Herbert Cranstoun/Cranston, Amy Berenice Merrick, Plomer Merrick Cranstoun, and John Merrick Cranstoun, 1911 Canada Census, Grenville, Ontario, district, 1916 Prairie Provinces Census, Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, district, 1931 Canada Census, Vancouver, British Columbia, district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 7 July 2025. Jack Sr.’s bankruptcy was reported in the official government Canada Gazette, 30 June 1923: https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=cangaz&id=5321&lang=eng&ecopy=cgc_p1-2_v056_n053_t000_000_19230630_p00001_z05247, accessed 13 July 2025.

[5] Cranstoun in Moose Jaw Maroons: https://www.eliteprospects.com/player/754251/merrick-cranstoun; Merrick and Jack Cranstoun in Vancouver Ex-King George team: ‘Curley Wheatley Nets Trail Counter With 15 Seconds To Go and Vancouver are Beaten’, Nelson Daily News (Nelson, BC), 2 March 1932; Vancouver Ex-King George: https://icehockey.fandom.com/wiki/Vancouver_Ex-King_George, accessed 8 July 2025. Jack Jr, American Football: ‘Pats Chalk Up 26–0 Victory Over Winnipeg in Junior Grid Final’, Morning Leader, 22 November 1926; Canadian Rugby: ‘Locals Pile on Points’, Sunday Sun (Vancouver, BC), 22 October 1928; Regina Pats and offered contract by Detroit: ‘Juniors Offered Jobs with Pros’, Calgary Daily Herald, 26 November 1926; helping for form junior baseball league in Regina: ‘Interest Is Lax In Junior Ball’, Morning Leader, 27 March 1929; Argos tour and playing againt Sid Bissett’s West End team in Winnipeg: ‘West End Team Defeats Regina’, Winnipeg Evening Tribune, 31 July 1926; Sid Bissett 1938 GB team: https://projectcobb.org.uk/gb_history.php?year=1938; Jack Cranstoun turning out for the Generals baseball team, Vancouver Terminal League: ‘Asahis Play Smart Baseball To Break Even With Generals’’, Vancouver Sun, 17 May 1928.

[6] https://www.arrow.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2022/04/Newsletter_Autumn18.pdf, accessed 8 July 2025.

[7] See 1930 and 1931 rosters for Arrow Transfer at the Western Canada Baseball website curated by Jay-Dell Mah: https://attheplate.com/wcbl/1930_1j.html and https://attheplate.com/wcbl/1931_1j.html, accessed 8 July 2025.

[8] Quoted here: https://attheplate.com/wcbl/1931_100i.html, accessed 8 July 2025. No citation is given except the date (27 April 1931).

[9] https://attheplate.com/wcbl/index.html, accessed 8 July 2025.

[10] See Note 7 above.

[11] My information on the Asahi is drawn from the Western Canada Baseball website (Note 8 above), and:

1. Eli Yarhi and Christopher Pellerin, updated by Clayton Ma, ‘Vancouver Asahi’, Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/vancouver-asahi, accessed 8 July 2025;

2. Tom Hawthorn, ‘Vancouver Asahi’, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-vancouver-asashi/;

3. Yobun Shima - Satoshi Matsumiya, ‘1921 Vancouver Asahi’s Tour of Japan’, https://sabr.org/journal/article/1921-vancouver-asahis-tour-to-japan/;

4. Ted Y. Furumoto and Douglas W Jackson, ‘More Than a Baseball Team: The Saga of the Vancouver Asahi’, (Taupo: Media Tectonics, 2012).

Documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxBWg4zxTkQ, accessed 8 July 2025. Movie: ‘Vancouver Asahi’ (Japan, 2014): https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3550344/, accessed 8 July 2025. Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame: https://baseballhalloffame.ca/hall-of-famer/vancouver-asahi/, accessed 8 July 2025. It has to be acknowledged that the Asahi were founded, funded, and coached by store owner Matsujiro Miyazaki, so in that sense, there was a business connection, although there is no suggestion that Asahi is the name of Matsujiro Miyazaki’s store. For Nishikawa’s involvement with Star Club, see Note 1 above.

[12] Quoted here: https://attheplate.com/wcbl/1931_100i.html, accessed 8 July 2025. No citation is given except the date (31 August 1931).

[13] https://baseballhalloffame.ca/hall-of-famer/roy-yamamura/, accessed 8 July 2025. Roy Yamamura’s story in Japanese: https://discovernikkei.org/ja/journal/2022/3/10/roy-yamamura/, accessed 9 July 2025.

[14] Note 7 above and Note 10 above, first reference.

[15] https://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/1935_100i.html, accessed 9 July 2025.

[16] Note 12 above, first reference.

[17] Leo Holden: https://www.ishilearn.com/doc-holden, accessed 3 August 2025. The quote comes from here: https://attheplate.com/wcbl/1932_100i.html, accessed 8 July 2025. No citation is given except the date (27 May 1932).

[18] https://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/1933_100i.html; https://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/1934_100i.html, accessed 9 July 2025. Jack Cranstoun, bank manager: ‘From the Four Corners: It’s Him’, Leader-post, 13 June 1947. Merrick Cranstoun refused amateur card: ‘A.A.U. Refuses Cards to Ball Players’, Vancouver Sunday Sun, 18 December 1934. Strikes deal to play ice hockey: Hal Straight, ‘Sport Rays’, Vancouver Sun, 25 March 1935. Merrick Cranstoun in the roster for Lowney’s Chocolate: ‘How Teams Will Line Up’, Vancouver Sun, 27 April 1935. Playing softball for the Castles: ‘Castle Stay Right With Haugh’s Crew, Beating Morrows’, Province, 28 May 1935.

[19] ‘To-night’s Ice Hockey’, Evening News (London), 7 December 1935.

[20] ‘Rinks to Form a Junior Ice Hockey League’, Weekly Dispatch (London), 13 October 1935.

[21] Empress Hall history: http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/EmpressHall.htm.

[22] https://icehockeyuk.co.uk/hall-of-fames/percy-nicklin/, accessed 9 July 2025.

[23] Shamateurism: Clifford Webb, ‘Ice Hockey Trek’, Daily Herald, 17 July 1936. Poaching: see Note 19 above.

[24] 11 players: Passenger lists for SS Montcalm, arriving Southampton, 13 October 1935—the men can be identified by name and by their address in England, ‘Empress Stadium’; Cranstoun’s arrival: passenger lists, SS Berengia, arriving Southampton, 26 November 1935, UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 9 July 2025.

[25] Al Male, ‘Gee! They’re Going to Put Baseball Over Big’, Daily Mirror, 30 April 1936.

[26] Daniel Bloyce, ‘John Moores and the ‘Professional’ Baseball Leagues in 1930s England’, Sport in History, 2007, 27:1, 64-87. Josh Chetwynd and Brian A Belton, ‘British Baseball and the West Ham Club’ (London: McFarland and Company, 2007); and Harvey Sahker, ‘The Blokes of Summer’, (Free Lance Writing Associates, Inc., 2011).

[27] I cover the story of baseball played under the English code here: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-intolerance, accessed 9 July 2025.

[28] There are various stories as to how Moores came to launch his attempt to reintroduce American baseball into the UK, discussed by Chetwynd and Belton, Note 25 above, second reference, pages 31–33, most of them assembled from the reminiscences of people long after the event; the version presented in this work is assembled from contemporary newspaper stories, see, for example, Moores as patron of the EBU and travelling to America: ‘Bees Notes on Sports: Ambassador to America’, Liverpool Echo, 28 March 1933; trying to persuade EBA and EBU to change to American code: ‘American Baseball to be Played in Liverpool Next Season’, Liverpool Evening Express, 12 August 1933. The involvement of John Heydler is from Moores’ own account given at the time; see, for example, https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/artefacts/1937-Challenge-Cup-2022-08-14.pdf, accessed 9 July 2025.

[29] For information of the Quebecois players, see Chetwynd and Belton, Note 26, above, second reference, pages 71–72 and 142–157 (the latter a chapter devoted to the career of Roland Gladu). Biographical information on Strong:passsenger lists, SS Acquitania arriving New York, 31 August 1937, which helpfully lists Strong’s occupation as ‘baseball’; Roland Gladu and George Etheze were also onboard, New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957; entry for Gerald K Strong, 1939 England and Wales Register, Wembley district. Information on Jake Asbell assembled from: passenger lists, SS Empress of Britain, arriving Southampton, 13 November 1934, UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960; entry for David J Asbell, Liverpool District, 1939 England and Wales Register; passenger lists, 2 August 1947, UK Outgoing Passenger Lists, 1890-1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 10 July 2025. For his Saskatchewan baseball career, see: https://attheplate.com/wcbl/1931_1j.html, accessed 9 July 2025. Jerry Strong is credited with pitching the first no-hitter game in England in: ‘To-Night’s Baseball: West Ham Players in Hull Team’, Hull Daily Mail, 15 June 1936. However, this appears to be a reference to Strong’s shut-out of Catford in early June, where Catford had players on bases (walks?): ‘Hammers the Only Unbeaten Baseball Side’, Daily Express, 2 June 1936.

[30] ‘First “Strike Out”’, Daily Mirror, 20 May 1936. Streatham-Mitcham were formed of players from the Rugby League team of the same name, including Māori star, George Nēpia: ‘Nepia at Baseball’, Daily News (London), 7 May 1936. They also employed the services of a 20-year veteran of the London baseball scene, Sacrimento native and US Embassy employee, Bertram Gildersleeve.

[31] Chetwynd and Belton, Note 26 above, second reference, cover Wood’s role in depth, pages 57–70.

[32] ‘Cheetahs Race on Track—Beat Greyhounds’, Sunday Mirror, 12 December 1937.

[33] See Chetwynd and Belton, Note 26 above, second reference, pages 87–91.

[34] Note 25 above, which is also the source for years of birth. Paul McPhail https://www.eliteprospects.com/player/359398/paul-mcphail; For Howie Peterson: Richard Macleod, ‘Newmarket’s a Hockey Town At Heart’, Newmarket Today, https://www.newmarkettoday.ca/remember-this/newmarkets-a-hockey-town-at-its-heart-14-photos-3157487, accessed 9 July 2025.

[35] See Note 24 above. Paul McPhail’s movements can be traced in Canada Census returns for 1921 and 1931, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 9 July 2025. See also: https://www.eliteprospects.com/player/359398/paul-mcphail, accessed 9 July 2025.

[36] See, for example, team list, ‘Week-End Baseball’, Evening News (London), 27 June 1936, and Al Male, ‘Al Male Feels Sore over Baseball’, Daily Mirror, 20 May 1936. For Roger Evans as umpire and coach at Streatham, see ‘Baseball: First Defeat for Streatham’, Streatham News, 26 July 1935. For Roger Evans, baseball player, umpire, thief, and prison escapee, see ‘Guilty of Preying on Women’, The People, 11 April 1937.

[37] Information on the Wasps team is drawn largely from Sahker, Note 26 above, third reference. These nicknames were a feature of the rosters printed in the game programmes, see, for example, https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/anthony_taylor/1936a_4.jpg, accessed 9 Juy 2025.

[38] ‘Cheetahs Race on Track—Beat Greyhounds’, Sunday Mirror, 12 December 1937.

[39] ‘Baseball Errors’, Sunday Express, 19 July 1936.

[40] See Note 3 above, and ‘Durex Beaten in National Cup’, Birmingham Daily Gazette, 3 August 1936. Sid Bissett biography up to 1936: ‘Bissett–Baseball Star’, Evening Dispatch (Birmingham), 7 May 1936. The latter perpetuates a myth that Bissett was born in Scotland on Christmas Day 1907. He was not; he was born in Manitoba on Christmas Day 1905 or 1906, and his real name was Donald Alexander Bissett. The full story I tell elsewhere, but, for our purposes, it is enough to know the following: 1) Bissett is listed as ‘D A (Sid) Bissett’ in the Durex roster here: ‘Baseball Match with Dark Blues’, Evening Dispatch (Birmingham), 4 June 1936; and 2) there was a Donald A Bissett working for an emery paper manufacturer (i.e., Durex Abrasives) living in Birmingham in 1939, who was born on Christmas Day 1906 in Canada: entry for Donald A. Bissett, Birmingham Borough, 1939 England and Wales Register, ancestry.co.uk. Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 12 July 2025.

[41] ‘Romford’, Essex Newsmen, 1 August 1936.

[42] https://www.mlb.com/glossary/rules/infield-fly, accessed 9 July 2025.

[43] ‘Romford’s Hard Baseball “Go” With West Ham’, Weekly Dispatch (London), 9 August 1936. Homer’s warning about fans’ ignorance of the rules: ‘West Ham Win First Match’, West Ham & South Essex Mail, 8 May 1936. ‘Homer’ was far and away the most knowledgeable about the game of the correspondents who covered the LMBL; given the pen name and his location—West Ham—we can speculate he was one of the West Ham players.

[44] Harringay Take Sting Out of Wasps’, Weekly Dispatch (London), 28 June 1936; ‘Big Hit Fails to Help Wasps’, Reynolds Newspaper, 28 June 1938.

[45] ‘Romford Wasps Lose’ Daily Mirror, 11 August 1936. Final League Standings: ‘Baseball Major League Table’, Evening News (London), 31 August 1936.

[46] It is worth pointing out here that, as was common practice in English sports of the period, Cranstoun’s title woud be ‘manager’, not ‘coach’.

[47] ‘Rangers Rout the Royals’, Daily News (London), 15 October 1936.

[48] https://icehockeyuk.co.uk/hall-of-fames/jimmy-foster/; https://icehockeyuk.co.uk/hall-of-fames/art-child/; https://icehockeyuk.co.uk/hall-of-fames/jimmy-chappell/; https://icehockeyuk.co.uk/hall-of-fames/gib-hutchinson/, accessed 9 July 2025.

[49] ‘Lefty Wilson, Tallie Ellis, Slim Tyson, Eddie Mumma, Stevens, and McNeece’: Al Male, ‘Ball Stars Are Going Home’, Daily Mirror, 21 August 1937.

[50] Dawber pitching for Pritchett & Gold: ‘No Vary–Nomad Clash’, West Ham and South Essex Mail, 13 August 1937. His later career is covered in his British Baseball Hall of Fame Entry at: https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/bbhof/index.html, accessed 10 July 2025.

[51] By 9 August 1937, Wasps had conceded 124 runs, compared to 263 by the end of the season the previous year, see League table, 9 August 1937: ‘Baseball Results’, Daily News (London), 9 August 1937.

[52] Robert F Hammond, ‘Nishikawa Pitches Corinthians To Victory’, South London Observer, 30 July 1937.

[53] Note 1 above and references therein.

[54] Al Male, ‘Corinthians Sign Japanese Star’, Daily Mirror, 29 May 1937.

[55] ‘Japanese Baseballers Are Here!’, Evening Express (Liverpool), 4 July 1933; Liverpool Echo, 16 September 1933; ‘EBL Games’, Evening Express (Liverpool), 14 June 1935; and ‘Japanese Team at Bootle’, Liverpool Daily Post, 10 June 1936.

[56] ‘Baseball Has Its Corinthians Now’, Daily Mirror, 9 April 1937.

[57] This churn of teams is covered by Chetwynd and Belton, Note 26 above, second reference, pages 158–159.

[58] ‘Baseball Season Opens’, Sydenham, Forest Hill, and Penge Gazette, 30 April 1937.

[59] https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/anthony_taylor/1937b_3.jpg, accessed 10 July 2025.

[60] ‘Pirates Outclass Leaders’, Daily Herald, 7 June 1937.

[61] ‘Baseball Results’, News Chronicle, 26 July 1937.

[62] See Chetwynd and Belton, Note 26 above, pages 142–157.

[63] ‘Wasps Are Baseball Champions’, Daily Mirror, 20 August 1937.

[64] Wasps champions: See Note 63 above; losing to Hull in the Challenge Cup final and Cranstoun’s acknowledging Wilson’s role: ‘Hull Worthy Winners in City’s First-Ever Baseball Cup-Final’, Hull Daily Mail, 14 August 1937. Lefty Wilson’s pre-UK minor league stats: https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Max_Wilson; post-UK major league stats: https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=wilsoma01, accessed 10 July 2025.

[65] This is discussed by Bloyce, Note 26, above, first reference. I cover the differences between the American and British codes elsewhere (Note 27 above).

[66] ‘Vigorous Ice Hockey’, Daily News (London), 18 October 1937.

[67] Cranstoun playing for Newcastle in IBL: ‘Hull’s Big Night of Baseball’, Hull Daily Mail, 25 May 1938. The story of the IBL: Note 26 above, third reference, pages 115–118. Nishikawa in IBL: ‘Nomad’, ‘Newcastle Test at Baseball’, Evening Chronicle (Newcastle), 14 June 1938.

[68] ‘Canadian Ice-Hockey Player’, Evening Telegraph (Dundee), 11 July 1938.

[69] Cranstoun’s recruitment by Hull: Baseball: Hull’s Yorkshire Cup’, Hull Daily Mail, 21 June 1939. Walking 12 Halifax players: ‘Hull Beaten 14–1—Out of N.B.A. Cup’, Hull Daily Mail, 24 July 1939. League result: ‘Home Run’, ‘Baseball Notes’, Hull Daily Mail, 12 August 1939.

[70] See, for example, ‘Perth’s Big Lead in Ice Hockey League’, Dundee Courier, 18 December 1939.

[71] Passenger lists, SS Duchess of Bedford, departing Liverpool, 25 May 1940, UK Outgoing Passenger Lists, 1890-1960, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 10 July 2025.

[72] For Spitfires: ‘Novan Defeat Spitfires’, Nelson Daily News, 16 December 1941. Officiating: ‘Mintos Lose Two—Lions Win’, Prince Albert Daily Herald, 22 December 1952.

Vancouver Sun, 14 March 1936. Image created by Google Newspaper Archive.

Vancouver, BC, amateur baseball leagues, 1931, reproduced from: https://attheplate.com/wcbl/index.html

Asahi Baseball Team, 1940, Canada Post stamp, 2019. Used with permission.

The Cranstoun brothers and Asahi's Roy Yamamura in the Arrow Transfer roster, 1931. Vancouver Sunday Sun, 27 August 1931. Image courtesy of Google Newspaper Archive.

Merrick brothers' PCT stats for the Vancouver Senior City League, reproduced from: https://attheplate.com/wcbl/index.html

Romford Wasps Baseball Programme, 1936. Author's own collection.

Roster, Romford Wasps Baseball Programme, 1936. Author's own collection.

Harringay Baseball Programme, 1936. Author's own collection.

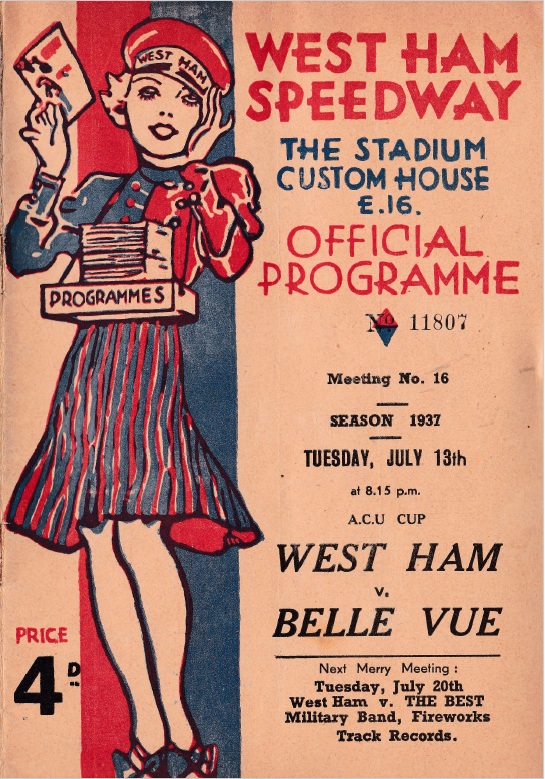

West Ham Speedway Programme, 1937. Author's own collection. The baseball team shared the Custom House stadium with speedway.

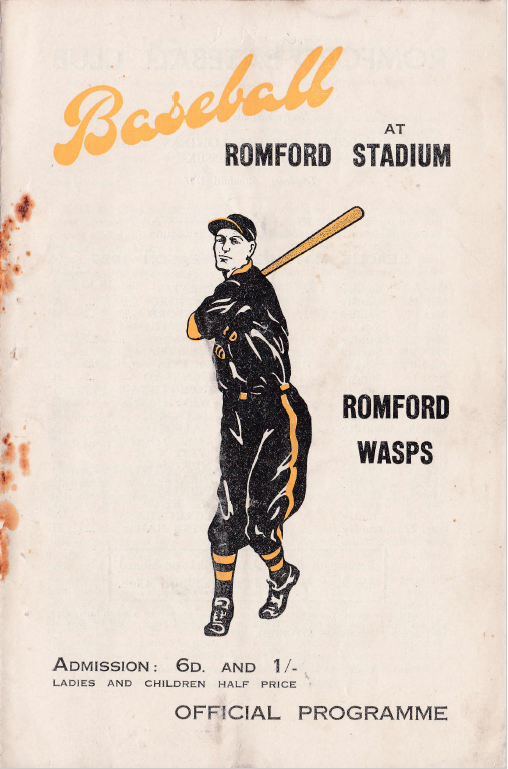

Romford Wasps Baseball Programme, 1937. Author's own collection.

Roster, Romford Wasps Baseball Programme, 1937. Author's own collection.

autographs, Jake 'Poison' Asbell, Gib Hutchinson (Romford Wasps), and Jack Robbins (Pirates), 1937 London Major Baseball League season. Author's own collection.

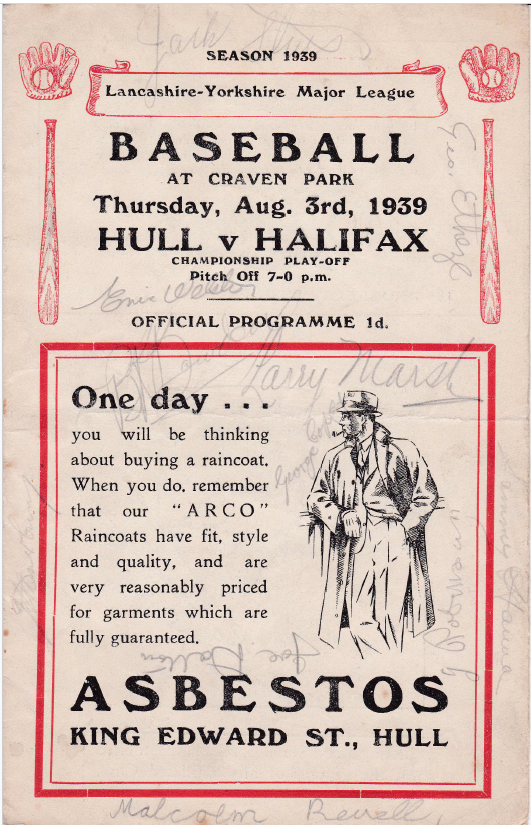

Hull baseball programme, 1939. Author's own collection.

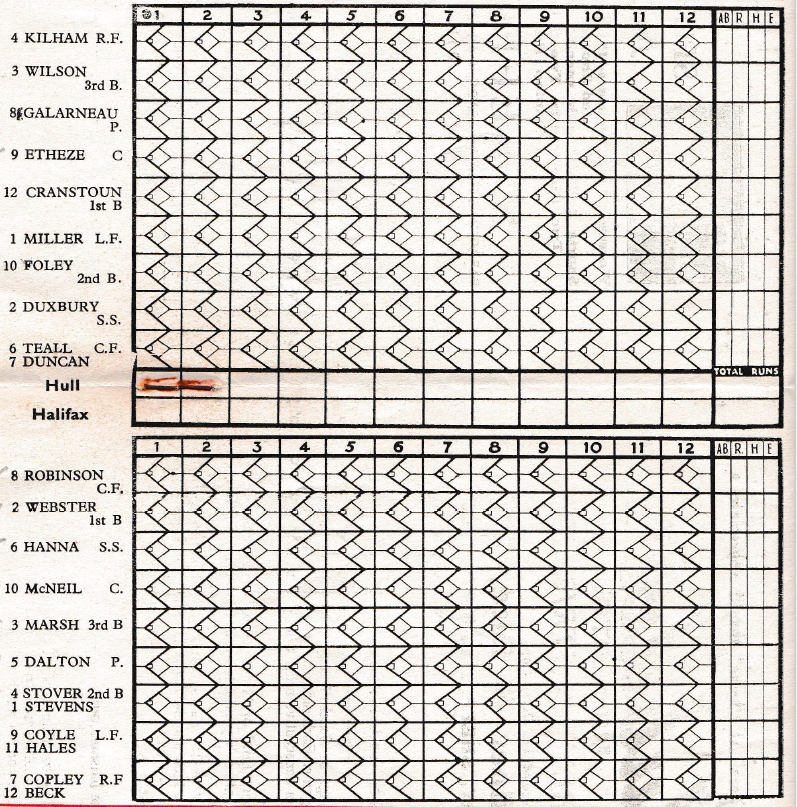

Rosters and scorecard, Hull baseball programme, 1939. Author's own collection.