Hullo, America!

Jamie Barras

The Two Bees (the Blakes) are always welcome at Chatham, where Harry and Flora have crowds of admirers, and the enthusiastic applause that follows them as they retire is no more than they deserve; these artistes are the first in the field with a song on the fast becoming popular game of Baseball.[1]

It is in many ways remarkable, given how direct the link between the music hall and the introduction of American baseball in Britain, and given the music hall’s love of novelty, that there is so little evidence of baseball being used as the subject of stage entertainment in Britain before the modern era. That is not to say that baseball songs were never sung in Britain, of course. Although it is possible that ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame’, that most famous of baseball songs, was performed on an English stage before the modern era, it was certainly sung at baseball games in Britain—and not just by the crowd: we can, for example, suppose that the ‘baseball song’ sung by three players following a charity game at Nelson in Lancashire in June 1937 was ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game’.[2]

However, my focus here is on providing examples of baseball-themed songs, plays, and other entertainments that found their way onto the British stage. It is not an overcrowded field, but each example is instructive and can even give us some clues as to why the sport itself was received the way it was in Britain before the modern era.

LONDON BASEBALL ASSOCIATION. THE game of Baseball first took root in London in 1892 when the team known as the Thespians was organised. The originators of the idea were Frank Halter, James Marco, Harry Athol, Geo. Hall Dare, Kelly and Ashby and R.G. Knowles.[3]

North American variety artists found a ready welcome in British halls in the late nineteenth century, and were to provide a pool of experienced players for the nascent British baseball scene. Indeed, the London baseball scene in the last decade of the nineteenth century was sustained by North American variety artists, centred, as it was, on the London Baseball Association and its flagship team, the Thespians, both of which were founded by Canadian-born comedian R.G. Knowles. We can also point to the efforts in Manchester of Scots-American actor and producer James M. Hardie, whose baseball team, based at his Regency Theatre in Salford, included African American and Native American stage performers. Hardie’s team seems to have played mostly against other companies of North American artists that appeared at the Regency.[4]

Yet, the first use of baseball as a subject for a music hall turn was, as far as we can determine, the work of two performers with no connection to the baseball scene itself.

The Two Bees. Droll Duettists, HARRY AND FLORA BLAKE. En route for England. Concluded Empire Theatre, Johannesburg. Instantaneous hit. Tremendous success. Perfect ovation nightly. Canterbury, Paragon, Collin’s shortly. Base Ball song (as a Dewar), a big hit. The Singing Contest (Sweetheart—Fondheart) still the rage. Agent—F. Napoli, 55 Waterloo, S.E.[5]

Harry and Flora Blake, ‘The Two Bees’, were the stage names of husband and wife singing duo Stephen Broughton Sanders (1862–1945) and Flora Antoinette Sanders (1865–1910). Although born in England—Lambeth, in Stephen’s case, Weybridge’s in Flora’s—they met and were married in America. It was also there that, in 1886, they started their show business careers as a singing duo—although Stephen/Harry had ben a solo child performer back in London. After a successful career in vaudeville, the Blakes/Sanders returned to Britain in 1894 and began touring the halls. They would have their biggest success in 1903 when they acquired the English rights to a musical setting of Longfellow’s poem ‘The Song of Hiawatha’, which they performed as a duet, exploiting the popularity of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s choral setting of the poem. However, within a few years of that success, Flora was forced to retire due to ill health. She passed away in 1910, aged just 46. After his wife’s death, Stephen Sanders/Harry Blake reinvented himself as a patter comedian and continued to perform successfully for many years; he also remarried (less than one year after Flora’s death and to a woman 20 years his junior). He died in 1945, aged 83.[6]

There appears to be very little concrete information about the baseball song sung by the Blakes. They debuted it in London in July 1896, but it appears to have been a feature of their act for only the rest of that year, most of which they spent on a tour of South Africa. I can find no evidence of it ever being published. However, we can make some guesses as to its theme and content from the title: ‘As a Dewar’. The Blakes debuted the song in the middle of the London Baseball Association’s third full season of baseball in the capital. Sir Thomas Dewar (1864–1930), the Scotch whisky distiller, was a prominent supporter of the London Baseball Association, serving as its president. He also donated a trophy to the Association and sponsored one of its teams, which was named after him.[7]

Given the above and the title, ‘As a Dewar’, it seems reasonable to suppose that the Blakes’ baseball song was sung in the character of one of the players of the Dewar’s team and made much of both the association with Scotch whisky and the similarity in pronunciation of ‘Dewar’ and ‘doer’. It is also worth noting here that at least two of the men closely associated with the administration of the London Baseball Association were songwriters: Richard Morton, who co-wrote (ghost-wrote?) R.G. Knowles’ 1895 book on baseball, and James McWeeney, who served as the Association’s organising secretary from 1896 onwards.[8]

"EL CAPITAN" AT THE LYRIC. Mr de Wolf Hopper and the American company, who have presented the British public with this most pleasing of comic operas, are to be congratulated upon the success that has attended their efforts to amuse, and the proof of which success is demonstrated in the crowded houses that are nightly charmed by the music and "go" of "El Capitan".[9]

Three years after the Blakes debuted ‘As a Dewar’, a new comic opera, ‘El Capitan’, a Broadway transfer with music by John Philip Sousa, opened at the Lyric Theatre in London. Comic operas and operettas, the forerunners of the book musical, were the source of much that was baseball-themed on Broadway in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Author Mark Schupin has done much to document the connection between baseball and the stage in America—including the surprisingly large number of times that baseball players took the stage—with special attention paid to comic operas.[10]

The 1899 London production of ‘El Capitan’ was to supply us with our next baseball-themed performance, although not in the way we might expect. ‘El Capitan’, which was set in what is now Peru at the time of the sixteenth-century Spanish conquest, did contain anachronistic references to baseball for comic effect; however, it cannot be said to be ‘baseball-themed’. Still, it is of interest to us for two reasons. The first is that, for its London production, the baseball references were removed,[11] which hints at why it is so difficult to find baseball-themed entertainment on the British stage: feeling that it would fall on stony ground, producers avoided casting it before British audiences. The second is because it brought to London a performer indelibly linked to baseball on the Broadway stage: William DeWolf Hopper (1858–1935), self-styled ‘baseball nut’, and the man who made ‘Casey at the Bat’ the most famous of all baseball-themed poems.

The story of DeWolf Hopper and ‘Casey at the Bat’ is well-known and much written-about; however, briefly, in 1888, while starring in a production of the comic opera ‘Prince Methusalem’ at Wallack’s Theatre in Chicago, and on hearing that the New York Giants and Chicago White Stockings baseball teams were to be in the audience, Hopper, at the suggestion of the writer Archibald Clavering Gunter, added to his performance a recitation of Ernest Thayer’s, at that time, little-known poem ‘Casey at the Bat’. It was a sensation, and audiences demanded it at the end of every stage performance and after-dinner speech that Hopper gave for years afterwards. Hopper grew heartily sick of the poem, but the public appetite for his performance was insatiable. Ultimately, Hopper would perform the piece tens of thousands of times, including for radio and audio and film recordings. Listening to surviving recordings now, it is hard to see the piece’s appeal, but one must make allowances for the poor quality of sound reproduction in early recordings and changes in performance style in the intervening years, much as with ‘classic’ horror films, like ‘Frankenstein’ and ‘The Old Dark House’.[12]

We can cite at least one instance of Hopper performing ‘Casey at the Bat’ during the London run of ‘El Capitan’, albeit not on the stage per se.

One of the finest items herein was ‘De Wolf Hopper’s recitation of his celebrated baseball poem “Casey at the Bat,” the reception of which nearly raised the Café Royal's roof. Whenever you have a chance of hearing this elocutionary “character” effort—hear it.[13]

Hopper performed the piece on 12 July 1899 in front of an audience of fellow thespians and other luminaries at a supper hosted by the Eccentrics Club at the Café Royal on Piccadilly. The supper was in honour of the unusually large number of American theatrical companies that were performing in London that season (known in theatrical parlance as ‘lambs’), and attendees included Hopper and other members of the ‘El Capitan’ company alongside members of the companies of ‘The Belle of New York’, ‘The Cowboy and the Lady’, and ‘An American Gentleman’, all American productions recently transferred to London.[14]

Two of the attendees at that supper are of additional interest to us here: Newton Crane and Burr Mackintosh. Newton Crane, an American newspaperman and lawyer resident in England, was the leading light of attempts to introduce American baseball in England in the 1890s and would feature in later attempts in one capacity or another for nearly 30 years afterwards. In April 1899, he was named president of the amateur ‘London Baseball Club’.[15]

Burr Mackintosh was an actor in the cast of ‘The Cowboy and the Lady’. Two days after the Café Royal supper, an article appeared in the theatrical press stating that ‘sundry variety and theatrical American citizens, now disporting in London, have resolved to challenge, at their national game of baseball, Mr. De Wolf Hopper and Company.’ One of the players mentioned in the article is Burr Mackintosh, alongside two other members of the company of ‘The Cowboy and the Lady’. It seems likely that the challenge was issued to Hopper and company at the Café Royal supper. Given the presence of Newton Crane at the supper, it may have been made under the auspices of the London Baseball Club. Alas, it is not known if this game took place.[16]

Although Hopper’s performance was at a theatrical supper, not on stage, what really set it apart from the Blakes’ performances of their baseball song was that Hopper’s audience was wholly theatrical and, in large part, American, and thus, receptive in a way that a wholly English general audience might not have been. He was preaching to the converted. As we have seen with the cuts made to ‘El Capitan’, producers were reluctant to chance their box office on how something as quintessentially American as baseball might be received. Yet, in the next decade, there would be evidence from the reception received by another quintessentially American sport on the London stage that, if given the chance, and if presented in the right way, English audiences might have taken to the novelty. However, before we leave 1899—and the century—behind, it is worth going back to the start of the year to acknowledge the presence on the English stage of not a baseball-themed entertainment but a baseball.

The bicycle-polo match, an almost new turn, is one of the most novel and attractive entertainments the Empire has ever introduced to the stage.[...]The ball, which is stated to be a leather base-ball, is propelled by giving it smacks, or pats, with the side of the wheel. You ride up beside the ball and jerk your front wheel round as if suddenly turning, and one of the prettiest pieces of play seen last night was the lifting of the wheel over the ball so as to get on the right side from which to strike it.[17]

Bicycle polo played without mallets, distinct from the version of the sport played with mallets, came to Britain from America. It is not surprising, therefore, that the ball used in the sport was a ‘regulation baseball’. The sport made its debut at the Crystal Palace in 1897, where it was played in an indoor arena. However, the two teams—which were named after and may have been sponsored by two American bicycle manufacturing companies, Columbia and Metropolitan—each consisting of two riders, then took the act on the road, as it were, playing the halls. They were still performing the act as late as May 1900.[18]

This, of course, has nothing to do with baseball, the sport; bicycle polo simply made use of the, to Americans, ubiquitous baseball. I present this diversion here simply to point out the irony of an entertainment making use of a baseball being a popular turn on the British stage for at least four years, while baseball, the sport, was, as the ‘El Capitan’ example shows, seemingly not even allowed to be mentioned, a caution that was surely not warranted given the reception that another American sport was to receive when presented on the London stage in the first decade of the new century.

"I expect one scene in ‘Strongheart' to rouse your audiences to enthusiasm. It is a football match scene containing all the excitement of the game without showing the game itself. The dramatic interest of this scene shows a conspiracy to break down one of the teams. I do not think there has ever been such a scene on your stage."[19]

I have written at length about the London productions of the American football-themed plays ‘Strongheart’ and ‘The College Widow’ elsewhere.[20] However, these two productions are worthy of mention here also for a number of reasons. The two plays debuted in London a year apart, starting with ‘Strongheart’ (actually, the second of the two plays to be written) in 1907. Neither play featured any scenes of actual football—all the on-field action happened off-stage—but collectively they gave British audiences their first glimpse of the culture surrounding the sport, with fiery locker room pep talks from cigar-chomping coaches, characters describing plays happening off-stage, using terms peculiar to the sport, and the players themselves, dressed in the now-recognisable uniforms and protective gear (1907 vintage), entering and exiting the scene.

As it would be another two years after ‘The College Widow’ closed before the first real American football games would be played in Britain, all of this was entirely new. Before ‘Strongheart’ debuted, all that the British public at large knew about the American version of football was what they read in disdainful British newspapers, which presented it as a barbaric, near-medieval trial by combat. Hardly a selling point for a popular entertainment. And yet this did not deter the backers of ‘Strongheart’ and ‘The College Widow’ from bringing their productions to London. And while ‘The College Widow’ flopped, and flopped badly, this was because its style of humour was poorly received, not its American football theme. ‘Strongheart’ was, in contrast, warmly received. All of which shows that British audiences’ lack of familiarity with not just baseball but also the culture surrounding it would surely not have been a barrier to them enjoying a baseball-themed play or comic opera if the work itself was good—if the producers had got the presentation right.

We can even point to a Broadway show with a baseball theme of this period that shared some of the plot elements of ‘Strongheart’ and some of the staging choices of ‘The College Widow’: Charles H. Hoyt’s 1895 play ‘A Runaway Colt’. Like ‘Strongheart’, ‘A Runaway Colt’ was centred on a star player who was a paragon of virtue and made the attempted corruption of the sport by gambling interests a feature of the plot; and like ‘The College Widow’, the climax of the play took the form of a game played off-stage, viewed by characters on-stage reacting to the unseen plays. Yes, ‘A Runaway Colt’ was a flop, but this is generally acknowledged to have more to do with the choice to cast actual baseball players in the principal roles than the play itself. It was written as a star vehicle for Adrian ‘Cap’ Anson of the Chicago White Stockings, the most revered player of its day, but Anson was simply not up to the task of playing the lead in a stage play (its failure was to haunt him for years). The author, Hoyt, died in 1900, which robbed the play of any hope of a revival in the US.[21]

However, none of this would have had a negative impact on a British audience, and we can point to a play we have already mentioned as one that flopped in America but became a smash in London: The Belle of New York, one of the plays whose company attended the 1899 Eccentrics Club supper at which DeWolf Hopper entertained, which ran for only 56 performances on Broadway, but over 600 in London. I would argue that all that would have been required for a baseball-themed entertainment to succeed on the British stage was someone to present it in the right way.[22]

We can, as far as the subject of ‘the College Widow’, ‘A Runaway Colt’, and baseball players on stage goes, make mention of two other points of interest of relevance to baseball in Britain: baseball great Ty Cobb, who visited Britain in 1929, starred in an American touring production of ‘The College Widow’ in 1911, while Arlie Latham, retired major leaguer and comedian of the diamond, whom we will meet again shortly in connection with the Anglo American Baseball League in London, made a characteristically disruptive guess appearance in a special performance of a scene from ‘A Runaway Colt’ during its short New York run. I will stretch my point a little and say that the reception that Anson, Cobb, and Latham received demonstrates the danger of relying on the wrong kind of star power when trying to put over something new; the messenger needs to fit the medium.[23]

Before we move from 1908, the year that ‘The College Widow’ opened and closed in London, somewhat improbably, this was also the year that cricket came to the London stage, not as a play or book musical—although there would be several prominent examples of both in later years—but as an actual sport, in the form of a series of games played on the stage of the Coliseum Theatre of Varieties in London’s West End. The teams were of four players each, recruited from the Middlesex and Surrey County XIs.[24] If nothing else, this once again demonstrates that the London stage was a broad church that surely could have found a place for baseball if a producer had been willing to take a chance on a baseball-themed entertainment and present it in a way that appealed to a British audience, coupled with the appropriate use of star power. Alas, no producer proved willing to take a chance of putting baseball on the British stage until there were Americans enough in London to enjoy it.

"HULLO, AMERICA!" at the Palace Theatre. Miss Irene Magley and the Palace Girls Play Baseball in the First Act. Baseball on the stage is one of the original ideas to be found in "Hullo, America!" and the charming players are Miss Irene Magley and the eight Palace Girls.[25]

“Hullo, America!”, a new revue, opened at the Palace Theatre in London in September 1918, five months after America entered the First World War. The typically threadbare plot, which was only there to hang the production’s musical numbers on, concerned a ‘wild American girl who comes to Europe as a stowaway and issues forth from the inside of a basket destined for the Y.M.C.A.’. The action moved from country to country, with the heroine, played by American actress Elsie Janis (1889–1956), enjoying one adventure after another while being pursued by a French admirer (played for at least part of the run by Maurice Chevalier). The piece was created as a vehicle for Janis, a star of Broadway and the West End who became one of the first American entertainers to perform for American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) troops on the front lines, something that earned her the title ‘the sweetheart of the A.E.F.’. In homage to this, one of the scenes in ‘Hullo, America!’ took place in the trenches.[26]

Coincidentally, Elsie Janis’s first recording, made back in 1912, was of a baseball song, ‘Fascinating Baseball Slide’.[27] Meanwhile, the ‘baseball scene’ in ‘Hullo, America!’ featured the Palace Theatre’s chorus girls in a choreographed performance showing a game being played at a port somewhere in England for the enjoyment of disembarking American troops and to the bemusement of the locals. A photograph of the scene published in The Sphere magazine towards the end of the revue’s run shows that the two teams were ‘Chicago’ and ‘New York’, almost certainly a reference to the 1913–14 World Tour undertaken by the Chicago White Sox and New York Giants, which reached English shores in February 1914. That the show’s writers would choose to reference this in the production design rather than the more topical games played between teams of US and Canadian soldiers and sailors is interesting—perhaps they felt that olive drab did not flatter the Palace chorus girls?[28]

Like the rest of the revue, the baseball scene was created to capitalise on the presence of so many Americans in London and the fascination of British audiences with all things American now that America was in the war. The revue ran for an impressive nine months in the West End before going on an extended tour of the provinces, and there was even a cast recording released of songs from the show.[29] Baseball-themed entertainment was having its moment.

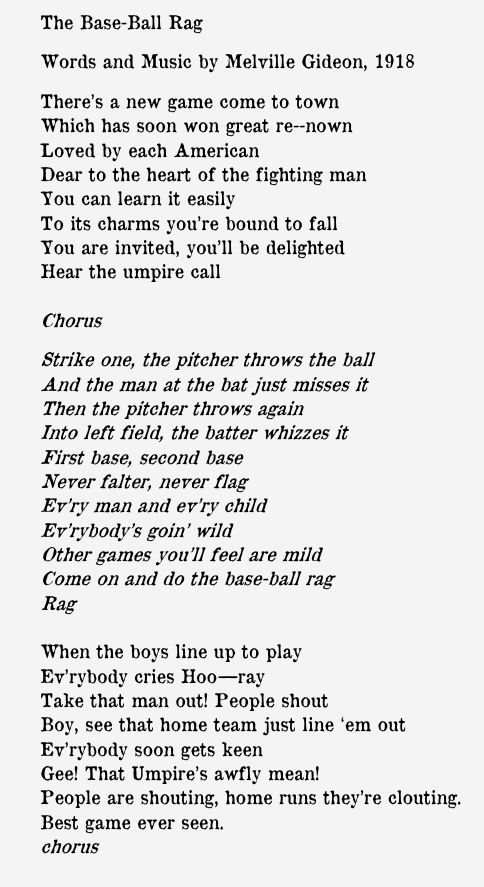

“The Baseball Rag". The official baseball song of the Anglo-American Baseball League, written and composed by Melville Gideon, and published by the Herman Darewski Music Publishing Company, has an appropriate swinging chorus.[30]

I have written about the London-based Anglo-American Baseball League of 1918–1919 elsewhere.[31] Fundamentally, its backers were applying the same logic as the producers of ‘Hullo, America!’ writ large: with large numbers of Americans in Europe and the British and French public’s newfound fascination with all things American, now was the time to [re]launch America’s favourite pastime in Europe as an overseas circuit of the major leagues. Alas, ‘Hullo, America!’ was to prove the longer-lasting of the two endeavours. Arlie Latham, the retired major leaguer and comedian of the diamond, whom we last met disrupting a special performance of ‘A Runaway Colt’ in New York in 1911, was the league’s official umpire, having moved to England in 1917.

Latham umpired the league’s biggest game, the 4 July 1918 game at Stamford Bridge between teams from the US Navy and US Army, which included King George V among its 10,000+ attendees. This occasion also marked the debut of the league’s official song, ‘The Baseball Rag’, written and composed by Melville Gideon (1884–1933).

Strike one, the pitcher throws the ball/And the man at the bat just misses it/Then the pitcher throws again/Into left field the batter whizzes it/First Base, second base/Never falter, never flag/ Ev’ry man and ev’ry child/Ev’rybody’s going wild/Other games you'll feel are mild/Come and do the baseball rag.[32]

Gideon, a New Yorker resident in London, was an accomplished ragtime pianist known for his deft skill at syncopation. He was also a hugely prolific songwriter—‘Hullo, America!’ was one of the few productions on the London stage in 1918 that didn’t feature one of his tunes.[33] The choice of Gideon, a ragtime composer, as the writer of the official song of the league makes plain just to what extent the backers of the league were pitching it as a forward-looking venture, something brand new and of the now, rather than a sentimental exercise for homesick doughboys. We can contrast this with the nostalgia evoked by ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame’, which was in waltz time.

The life that Gideon’s ‘Baseball Rag’ had beyond pre-game entertainment at league baseball games is uncertain. We can point to it being performed in a revue in the year it was published, but not much more.[34] But, then, it was meant to be ephemeral, of the now. We can also point to it helping to launch the career of Britain’s greatest songwriter of the early twentieth century, Noël Coward (1899–1973), as Coward’s first published credit as a lyricist was his own take on a Baseball Rag, published the year after Gideon’s effort (surely not a coincidence), with music by Doris Doris. It is fair to say that it was not one of Coward’s best efforts.

I’ve got a ripping new sensation/There’s no need for hesitation/Baseball’s the game that makes the world go round/It gets your heart a-palpitating/You can’t sit still/You’ll go mad, you’ll go bad/because you’ll never be contented until/You do that raggy rag.[35]

It is also safe to say that, as a comparison of the lyrics shows, unlike Gideon, Coward had little to no experience of baseball, even as a spectator. But, then, this makes the point that interest in the game had gone beyond its identity as a sport and embraced its status as a representation of America, fresh and new (to European eyes). It is fitting then that it was in the new medium of cinema that baseball-themed entertainment would finally make a lasting mark in Britain. However, we have one last stage production to consider.

BRITAIN'S NEWEST SPORTING FIXTURE "DAMN YANKEES" (Coliseum). A more unlikely story to captivate the hearts of an introspective English cricket-loving audience couldn't be found than this Faustian fantasy of an elderly baseball player who is re-given his youth (Ivor Emmanuel, right, bottom left) by the Devil (Bill Kerr, right) to help his home team beat those damn Yankees.[...]It is undoubtedly a tough proposition, but I shall be surprised if the punch that this musical packs does not do the trick once more. There is nothing wrong with the punch insofar as it aims at driving home the excitement and glamour of a ball game that ought to leave us cold. Much the best scenes in the show, paradoxically, are those that deal directly with baseball. Elsewhere the punch may possibly miscarry, but not here. The team in all the glory of their strange clobber have some crashingly good songs.[36]

The debut on the London stage in March 1957 of ‘Damn Yankees’, with music and lyrics by Richard Adler and Jerry Ross, brings together everything we have highlighted here: in judging the reaction of British audiences to baseball-themed entertainment on the British stage, it is the quality of the work, not whether or not it presents a world familiar to audience members, that determines the work’s fate. ‘Damn Yankees’, a smash on Broadway, was a disappointment in the West End; however, this had nothing to do with the fact that it was American—Adler and Ross’s previous musical, ‘The Pyjama Game’, was a hit in the West End—or that it contained baseball elements—which were generally praised in reviews—and everything to do with the complicated book and a poorly judged piece of stunt casting in one of the pivotal roles: former figure skater and B-list movie star Belita as temptress Lola (“a striptease that was poor to the point of embarrassment”).[37]

In all those respects, the fate of ‘Damn Yankees’ in London harkened back to the fate of ‘A Runaway Colt’ in America five decades earlier. It was not the baseball theme that was the problem; it was the presentation, the packaging, and reliance on the wrong kind of star power.

Dare I say the same that could be said of attempts to launch the sport itself in Britain before the modern era?

Jamie Barras, November 2025.

Back to The Spectacle

Notes

[1] ‘Provincial Babble: Chatham—Barnard’s Palace of Varieties’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 3 July 1896.

[2] The story of ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game’: https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/TakeMeOutToTheBallGame.pdf, accessed 11 November 2025. ‘Baseball song’ at exhibition game: ‘Baseball at Nelson’, Nelson Leader, 18 June 1937.

[3] ‘London Baseball Association’, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 6 July 1895.

[4] For the story of the London Baseball Association and the Thespians, see: R.G. Knowles and Richard Morton, ‘Baseball’, George Routledge and Sons, London, 1896. Free to download from archive.org: https://archive.org/download/baseball_202409/Baseball.pdf, accessed 9 January 2025. Richard Morton was a writer of songs for the music hall. For James M. Hardie’s Regency Theatre team, see: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-behind-the-mask, accessed 11 November 2025, and ‘Baseball: The Game in Manchester’, Sporting Life, 7 July 1898.

[5] ‘Advertisements and Notices’, London and Provincial Entr'acte, 9 January 1897.

[6] Information assembled from the following: ‘Death of Flora Blake’, Era, 29 October 1910; report of Flora Blake’s funeral, which mentions F.W. Sanders, the brother of ‘Harry Blake’: ‘Funeral of Flora Blake’, Era, 5 November, 1910; http://www.performingartsarchive.com/Vaudeville-Acts/Vaudeville-Acts_T/Two-Bees/Two-Bees.htm, accessed 11 November 2025; census entry for Stephen B Sanders and Flora A Sanders, Lambeth district, 1901 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 11 November 2025; death registration, Flora A Sanders, 1910, and death registration, Stephen B Sanders, 1945, search Births, Marriages, and Deaths, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl.

[7] Debut of Blakes’ baseball song: see Note 1 above. Tour of South Africa: see Note 5 above. Sir Thomas Dewar and London Baseball Association: Knowles and Morton, Note 4, first reference, 64–66. Dewars baseball team playing Thespians: ‘Baseball: Dewar’s v Thespians’, Sporting Life, 7 June 1895.

[8] Richard Morton: see Note 4 above, first reference, and ‘Death of Mr. Richard Morton’, Era, 9 March 1921. James McWeeney: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-health-friendship-and-baseball-part-i, accessed 12 November 2025.

[9] ‘“El Capitan” at the Lyric’, St Pancras Gazette, 28 October 1899.

[10] Mark Schubin, Baseball and Opera, https://www.sportsvideo.org/2014/05/05/baseball-and-opera/, accessed 12 November 2025.

[11] ‘Our London Correspondence: Dramatic and Musical’, Glasgow Herald, 11 July 1899.

[12] I draw on the version of the story given here: John Thorn, ‘Casey at the Bat: the Controversy’, https://caseyatthe.blog/blogs/caseyatthe-blog/casey-at-the-bat-the-controversy-part-1, accessed 12 November 2025. Hopper reciting the poem on record in 1906: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X8fTrc9Cymk; on film in 1923: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSeKK7zcPc8, accessed 12 November 2025.

[13] ‘Dramatic and Musical Gossip’, Referee, 16 July 1899.

[14] See Note 13 above and ‘Mr. De Wolf Hopper’s Speeches’, African Critic, 12 August 1899. ‘Cowboy and the Lady’ is not mentioned specifically, but we can cite the presence at the supper of Burr Mackintosh, who was in the cast of that show: ‘Chit Chat’, Stage, 1 June 1899.

[15] I discuss Newton Crane here: https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-intolerance, accessed 12 November 2025.

[16] Burr Mackintosh in Cowboy and the Lady: see Note 14 above, final reference. Challenge issued: ‘Sundry variety…’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 14 July 1899. The other two Cowboy and the Lady cast members mentioned in the latter article were Clarence Handysides and Tom Oberle. London Baseball Club: ‘Baseball: Formation of a London Club’, Pall Mall Gazette, 14 April 1899. Thanks are due to Andrew Taylor of the Folkestone Baseball Chronicle Facebook page for bringing this challenge to my attention. Andrew has written about Hopper and this challenge for his Facebook page.

[17] ‘The Empire Theatre’, Morning Post, 24 January 1899.

[18] Bicycle polo with mallets: https://www.polo-velo.net/english/history/history.htm, accessed 12 November 2025. ‘Regulation baseball’, debut at Crystal Palace: ‘Bicycle Polo’, Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 28 August 1897. Still being performed 1900: ‘Around the London Halls: The Empire’, Athletic Chat, 16 May 1900.

[19] ‘Mr Frohman’s Futures’, The Referee, 21 April 1907.

[20] https://www.ishilearn.com/the-spectacle-strongheart, accessed 12 November 2025.

[21] Robert H. Schaefer, ‘Anson on Broadway: The Failure of ‘A Runaway Colt’’, https://sabr.org/journal/article/anson-on-broadway-the-failure-of-a-runaway-colt/, accessed 12 November 2025.

[22] Scott Miller, ‘Curtains Up, Lights Out, 1874–1900’, https://www.newlinetheatre.com/musicalcomedy.html, accessed 12 November 2025.

[23] Ty Cobb in ‘The College Widow’: see Note 10 above, and Robert Edelman, ‘Ty Cobb, Actor’, https://sabr.org/journal/article/ty-cobb-actor/, accessed 12 November 2025. Latham in ‘A Runaway Colt’: see Note 21 above.

[24] Martin Williamson, ‘When Cricket Hit the West End’, https://www.espncricinfo.com/story/rewind-to-1908-when-cricket-hit-london-s-west-end-710639, accessed 12 November 2025.

[25] ‘Hullo, America! at the Palace Theatre’, The Sphere, 17 May 1919.

[26] Plot and cast for ‘Hullo, America!’ from Note 26, above, and: ‘Hullo, America!’, Pall Mall Gazette, 21 September 1918. Elsie Janis: Eric Trickey, ‘The Sweetheart of the American Expeditionary Force’, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/sweetheart-aef-180969241/, accessed 12 November 2025. Photo of Elsie Janis in ‘Hullo, America!’: Elsie Janis, National Portrait Gallery, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw203564/Elsie-Janis-in-Hullo-America, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/, accessed 13 November 2025.

[27] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84aPkozicqk, accessed 12 November 2025.

[28] See Note 25 above.

[29] ‘Hullo, America!’ ending its run in London in July 1919: ‘Frances Doesn’t Fly’, Leeds Mercury, 29 July 1919. Tour of the provinces: ‘Theatre Royal & Empire, Peterborough’, Peterborough Standard, 15 October 1921. Cast recording: advertisement for His Master’s Voice Records, Civil and Military Gazette (Lahore), 20 August 1919.

[30] ‘“The Baseball Rag”’, Halifax Daily Guardian, 5 July 1918.

[31] https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-never-falter-never-flag, accessed 12 November 2025.

[32] See Note 30 above.

[33] ‘Melville Gideon’, Gloucestershire Echo, 11 November 1933. https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/102823/Gideon_Melville, accessed 13 November 2025. Portrait: Melville Gideon, 1916, Bassano Ltd, National Portrait Gallery, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw52024/Melville-Gideon, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/, accessed 13 November 2025.

[34] ‘New Theatre, Cambridge’, Cambridge Daily News, 31 December 1918.

[35] Sheet music, The Baseball Rag by Noel Coward and Doris Doris, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2023796014/, accessed 13 November 2025.

[36] ‘Britain’s New Sporting Fixture’, Tatler, 10 April 1957.

[37] Review: ‘Poor “Damn Yankees”’, West London Observer, 5 April 1957. ‘strip tease’: see Note 36 above.

Baseball scene, 'Hullo, America!', Sphere 17 May 1919. Author's own collection.

'As a Dewar', baseball song, the Two Bees, London and Provincial Entre'acte, 9 January 1897. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Flora Blake (Flora Antoinette Sanders), Era, 29 October 1910. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

The Baseball Rag, Melville Gideon, Hull Daily Gazette, 5 July 1918. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Melville Gideon, 1916, Bassano Ltd, National Portrait Gallery, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw52024/Melville-Gideon, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Cover of the score of Melville Gideon's Base-Ball Rag, 1918. Copy held in the British Library.

Lyrics, Melville Gideon's Base-Ball Rag, transcribed from the copy held in the British LIbrary.

Cover of Noel Coward and Doris Doris' Baseball Rag, 1919. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Elsie Janis in ‘Hullo, America!’, National Portrait Gallery, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw203564/Elsie-Janis-in-Hullo-America, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Cast recording, 'Hullo, America!', Irish Independent, 2 December 1918. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.