They See Nothing at All

Jamie Barras

MR MONSON HYPNOTISED IN EDINBURGH. There was an overflowing audience in the Operetta House, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, last night, in consequence of the announcement that Mr A.J. Monson, the central figure in the Ardlamont mystery, was to be hypnotised by Mr Morritt. In fulfilment of his pledge, Mr Monson presented himself on the stage between nine and ten o’clock, and was received with applause mingled with hisses. As soon as he had been, to all appearance, successfully hypnotised, Mr Morritt invited the audience to send up any questions which suggested themselves in connection with the famous trial which aroused so much interest in the country about eighteen months ago.[1]

There have been few acts brought to the British stage as cynical as that in which illusionist Charles Morritt purported to put suspected murderer Alfred John Monson into a trance and interrogate him about the alleged crime. But, then, Morritt, although unquestionably a gifted illusionist, was a man who lived his whole life in the singleminded pursuit of money and fame, without any reference to morality. Being as he was, there was no other Troy for him to burn.

The Varieties, Leeds, has changed hands, the new lessee being Mr. Charles Morritt, a late employé of the establishment during Mr. Stansfield's reign.[2]

Charles Herbert Morritt (1859–1936) was born in Saxton in Yorkshire, the son of a prosperous farmer. By 1878, he was working as the secretary to John Stansfield, the lessee of the Varieties Music Hall in Leeds. The Varieties, better known as the City Varieties, still exists, a very rare survivor from the age when music halls were simply additional space for entertainment built onto public houses, in the case of the Varieties, the White Swan Inn in the centre of Leeds.[3]

Eighteen Eighty-One found Morritt living as man and wife with Adelaide Brown Howell (1855–1930), although they would not actually marry until April 1883. Ada would go on to play a very important role in Morritt’s stage career, but in time, he would desert her.[4]

Still working as Stansfield’s secretary at the time of his marriage to Ada, by September 1884, aged just 25, Morritt had made the leap to lessee of the Varieties and White Swan Inn, taking over from his former employer. The Bohee brothers would be one of the earliest acts that Morritt booked into the Varieties.[5] Just two months after taking over the music hall, he embarked on his first attempt to cash in on a famous court case.

NOTICE—All Communications respecting Engagements for Sir R.C.D. TICHBORNE, the Claimant, must be made to CHARLES MORRITT, Varieties, Leeds. Tour—Monday next, GLASGOW, following on to Halifax, Bradford, Manchester, Wigan, Goole, Doncaster, Liverpool, Southampton, Brighton, Portsmouth, Birmingham, Rochdale, Preston, Hull, London, &c.[6]

The saga of the Tichborne Claimant began with a shipwreck, continued with an outrageous and inept fraud, was sustained by the need of a grieving mother and the greed of the men around her, and culminated in two trials, one of which was the longest in English legal history to that date. It ended with Arthur Orton, the man who had spent 6 years falsely claiming to be Roger Tichborne, the heir to the Tichborne baronetcy, thought lost at sea but returned to life, being exposed as a fraud and jailed for perjury. The story is well known, and I will not dwell on it here. It is enough to say that Orton, in his lifetime, universally referred to as ‘the Claimant’, was released from prison in October 1884 and immediately renewed his false claim that he was Roger Tichborne.[7]

Shortly after Orton’s release, Morritt became his manager, booking him into music halls the length and breadth of the country, ostensibly so that the Claimant could make his case direct to the great British public, but in reality so that the latter could feast their eyes on this most famous of ex-convicts. By 1886, however, that well had run dry, and the Claimant crossed the Atlantic to make his case to the American public instead. This US tour was a disaster, playing to empty theatres, and by the autumn of 1887, he was to be found tending bar in a New York saloon.[8] He will make a second appearance in our story later; however, for now, we will leave him there. Because, by this time, Morritt had suffered his own reversal.

FAILURE OF A MUSIC-HALL LESSEE. Re CHARLES MORRITT, Lessee of the Varieties Music Hall, Leeds—A meeting of the creditors of this estate was held yesterday, at the offices of Mr. John Bowling, Official Receiver, Leeds. The debtor’s statement showed total liabilities £2,671 […] He took the Varieties Concert-hall, Leeds, on a lease for seven years. A partner was joined with him at one time, but he had since paid out the partner. Last September the debtor took the Star Concert-hall at Bradford on a lease for four years, and last October he also took the Princess Palace Concert-hall, Leeds, and worked it within a few days of his bankruptcy.[9]

In what was to become the theme of Morritt’s life, in his pursuit of money and fame, he took a good idea and ran it into the ground, losing everything in the process. A man with a knack for what would go over with the British public, Morritt proved adept at crafting programmes at the Varieties that brought in the punters. However, never one to be content with mere success, Morritt decided that, if he could create a money-spinning bill for one music hall, why not for two, or even three? Working initially with a partner named Edbell, but then on his own, Morritt went on a spending spree, leasing two more music halls and associated licensed premises in Leeds and Bradford, running up large debts to suppliers of wines and spirits in the process (alcohol was also to become a theme of Morritt’s life). In 1886, he finally over-reached himself and was declared bankrupt with debts of over £2,500—around 20 times the annual wage of an ordinary worker of the period.[10] He was 27 years old.

There are two versions of the next few years of Morritt’s life. After he became a success as an illusionist, he would claim that he spent these years in America, learning the craft at the elbow of the great French-born illusionist, Alexander Herrmann, aka Herrmann the Great, alongside another of Herrmann’s assistants, Billy Robinson, who would later gain fame as ‘Chung Ling Soo’ (an act Robinson famously stole wholesale from genuine Chinese stage magician, Ching Ling Foo (金陵福, Jīn Língfú)).[11]

The truth, contained in contemporary newspaper accounts, is that Charles and Ada Morritt spent most of those years in Britain. Remarkably, and again, a testament to Morritt’s recognised skill at crafting variety bills that brought in the punters, even while his bankruptcy case worked its way through the courts, he was allowed to not only continue to run the Varieties but also to take on the lease of the Mechanics’ Hall in Hull.[12] More significantly for our story, he also took his first steps as a professional performer himself.[13]

A MYSTERIOUS COUPLE. Remarkable exhibition of Transmission of Thought. “Transmission of thought” is a new practice. As yet it is not fashionable, but there’s no telling how soon it will become the rage, for the persons introducing it into this country are English. Charles Morritt, a long and slim gentleman, with white gloves, and accompanied by his wife, Lillian Morritt, gave a really remarkable exhibition at the Academy of Music last night.[14]

‘Lillian Morritt’, who in England for mysterious reasons was billed as Morritt’s sister, was Ada, his wife. The act, which in its earliest form was the familiar trick of the mind-reader’s assistant (Charles Morritt) circulating among the audience collecting items for the blindfolded mind-reader (Lillian Morritt) to identify—using a code based on the length of pauses between the words that Morritt spoke as he handled the objects[15]—evolved over time into an act centred on feats of memory and mental calculation on the part of ‘Lillian’.

[..] blindfolded, and apparently insulated from any means of communication, [Lillian Morritt] solves a number of arithmetical and other problems, the modus operandi of each feat being quite inexplicable. It is true that the lady’s brother, Mr. Charles Morritt, takes part in the entertainment, but less than persons in the audience, and although, doubtless, some code devised between the chief performers gives the cue for the solution of the problem introduced, it is yet so subtle and inexplicable as to be very surprising. A bank note handed from the audience has its value assessed and its number told by the quasi sorceress, and she as readily gives the dates of coins, and the accurate sum of rows of figures, each extending to tens of thousands.[16]

This evolution, unquestionably prompted by Ada Morritt’s excellent memory and gift for mental arithmetic, demonstrated by her mastery of the counting-pauses code, also reflected Charles Morritt’s acute understanding that audiences in time become wise to conjurer’s tricks.

Take, for instance, the old style of second sight. When it was first invented, it was wonderful; but nowadays, if you were to give an entertainment on the same lines, you would find that most of the members of even an ordinary audience could explain the whole thing to you.[17]

The Morritts toured their mind-reading act through Britain across the summer and autumn of 1888 to such success that they were offered a contract by a Pittsburgh-based theatre manager, Harry Williams, to tour the Eastern seaboard of the USA. Arriving at the end of October 1888, the Morritts, as the centrepiece of Williams’ ‘Anglo-American Star Company’, played Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Washington, DC, Baltimore, and New York to some acclaim before settling in for an engagement as part of Williams’ own in-house company at his Harry Williams’ Academy of Music theatre in Pittsburgh that was to last into the early months of 1889.[18]

This Evening, and every evening during the week. Engagement, for positively five nights only, the first appearance in Liverpool of CHARLES & LILLIAN MORRITT, in their new mysterious entertainment, embracing Science, Study, Theory, and Confusion combined.[19]

By the summer of 1889, the Morritts were back in Britain and ready to embark on the next, and most artistically significant stage of their career: a three-year-long engagement at Maskelyne and Cooke’s Egyptian Hall. John Nevil Maskelyne (1839–1917) and George Alfred Cooke (1825-1905), the former a watchmaker, the latter a cabinet-maker, were the foremost creators of illusions of the Victorian age. They ran the Egyptian Hall on Piccadilly for a staggering 31 years and in the process made it the home of stage magic in Britain.[20]

The invitation extended to the Morritts to join the Egyptian Hall company placed them in the top rank of illusionists in the country. Together, and separately, the Morritts would become integral members of the company, with Charles Morritt co-creating illusions with Maskelyne and Ada/Lillian Morritt acting as an assistant in Maskelyne and Cooke’s most elaborate productions, prime among them the Disappearing Lady trick.[21]

By the autumn of 1892, however, Morritt was ready to go it alone. In October of that year, he moved just down the street from the Egyptian Hall to the Princes’ Hall and debuted a new variety bill centred on two of the illusions for which he is now most known: ‘FLYTO’ and ‘The Missing Lady’. FLYTO involved the miraculous transference of a female assistant from a cage on the floor of the auditorium to one suspended in midair above it. Modern research has shown that this was stolen more or less wholesale from an act by Austrian stage magician Chevalier Ernest Thorn called The Chair of Khalif. Meanwhile, the Missing Lady illusion plays an important role in our story, as Morritt was to rework it twice in the following years, as we will see. As the name suggests, it was another disappearing act, this one involving a female assistant being bound to a chair and then raised into the air before disappearing, seemingly in full view of the audience, as a shot is fired at her. Lillian Morritt was given solo billing for her ‘thought transmission’ act, for which she was given the billing ‘the lightning calculator’.[22]

It is worth taking a moment to address this question of the origins of Morritt’s illusions, beyond mere theft. Morritt took out a number of patents throughout his career; on most of these, he is listed as the sole inventor. However, two patents filed at the time that Morritt was working up FLYTO and the Missing Lady are of special interest to us: ‘Improvement in Apparatus for Producing Stage Illusions’ and ‘Improvements in and relating to Stage Lighting for the Production of Stage Effects’. What sets these two patents apart from others that Morritt filed is that there is a second inventor listed for both: Joseph Winson.[23]

Joseph Henry Winson (1858–?) was a Lincolnshire-born illusionist and inventor who performed alongside his wife Annie. In 1892, during a long engagement at the Crystal Palace, he premiered his latest creation, ‘Gone’, an illusion in which Annie was manacled to an executioner’s chair and then hauled into the air; a switch was flicked, lights blazed, and Annie disappeared. This is, of course, the prototype of Morritt’s Missing Lady illusion. We can extend this comparison to look at an illusion that Morritt introduced in 1893, ‘The Flying Lady’, the now familiar illusion of making it seem as if someone is levitating and passing metal loops over their body to ‘prove’ there are no wires. As Winson later pointed out in print, this was his illusion, ‘the Maid of the Moon’, which he debuted at the Crystal Palace in 1891, reworked by Winson for Morritt. Indeed, in 1894, in an act called ‘Morritt and Winson’s Wonderland’, both the Flying Lady and the Missing Lady were attributed to both men as ‘their’ illusions.[24]

Thus, with FLYTO stolen from Thorn (with Winson’s help?) and the Missing Lady and the Flying Lady bought from Winson, we can state that Morritt did not create three of the illusions for which he was most famous in the early part of his career. Although an accomplished stage performer, he was, first and foremost, a man skilled in seeing the potential in the work of others to go over with the public, just as in his days creating the weekly bill for the Varieties.

After performing FLYTO and the Missing Lady for a year and a half, for the 1894 season, Morritt would make changes to both illusions to refresh them. FLYTO became ‘The Convict’s Escape’ by simple virtue of reducing the number of cages from two to one and adding a bit more business on stage to set the scene. Meanwhile, the Missing Lady became the Missing Man, with the female assistant replaced by none other than the Claimant, back in Morritt’s employ after an eight-year absence.[25]

However, the Claimant’s return was to prove short-lived, as within a month, Morritt, with typical ruthlessness, replaced him with someone connected to a far more recent court case—in fact, someone who was, in theory, a wanted man.

THE ARDLAMONT TRAGEDY. ALLEGED DISCOVERY OF SCOTT. The "Glasgow Evening News" says that it has it on good authority that Scott has been discovered and identified. He will be forthcoming at the trial next month in Edinburgh. It is stated, he is a bookmaker, and that he has been in hiding since the tragedy, and that he is an associate of Monson. The Exchange Telegraph Company's representative was informed on inquiry at Vine-street Police-station, London, last evening, that the rumour to the effect that "Scott," the missing man in the Ardlamont case, had been discovered, has no foundation. When found he will be arrested and conveyed forthwith to Scotland.[26]

The Ardlamont Tragedy was one of the most notorious criminal cases of the Late Victorian age. It centred on the cause of death of Windsor Dudley Cecil Hambrough, the 20-year-old heir to a Northamptonshire country estate, who died while a guest of the Ardlamont Estate in Argyll, Scotland. Again, it is beyond the scope of this piece to go into the details of the case; suffice to say that two men were accused of murdering Hambrough and trying to pass the crime off as a hunting accident: Alfred John Monson, Hambrough’s tutor and host for the visit to Ardlamont, and Edward Scott, aka Edward Sweeney, an associate of Monson’s from London. The death, initially ruled an accident, was reinvestigated when, two weeks later, Monson revealed that he had taken out two insurance policies in Hambrough’s name (which were in fact invalid, as Hambrough was still a minor in the eyes of the law, and, therefore, could not sign his name to anything—this element of the affair was never adequately explained). Monson was arrested, but Scott fled. At Monson’s trial, despite the wealth of evidence against him, because of a lack of any witnesses to the alleged crime or a motive— particularly, given that Monson, if he had evil intent, had every reason to keep Hambrough alive until he reached 21 and came into his fortune—the jury returned a verdict of ‘Not Proven’, an outcome peculiar to Scottish law. With that, Monson was a free man. However, in theory, Scott remained a fugitive.[27]

THE ARDLAMONT MYSTERY—THE PROPOSED LECTURES BY MR MONSON. For Saturday afternoon, Mr. Morritt, who has for some time been in possession of Prince's Hall, Piccadilly, had announced the commencement by Mr. A. J. Monson of a series of lectures on the recent Ardlamont trial. A number of people exhibited curiosity to hear the discourse, but when they reached the ticket-office it was to learn that their journey had in this respect been fruitless, Mr. Morritt is stated to have engaged Mr. Monson to give a twenty-minutes’ lecture twelve times a week for eight weeks, to be extended, at Mr. Morritt’s option, to twelve months. It appears, however, that Mr. Monson’s friends wished him not to enter upon such an engagement, and he adopted their advice.[28]

Morritt’s first attempt to make money from the tragedy was a repeat of his first involvement with the Claimant: to put Monson on stage to ‘make his case’ to the British public, but, actually, to let them gawp at him. The attempt failed because Monson was involved in litigation with Tussaud’s Waxworks over effigies that the company had made of him for display, and his solicitors did not want Monson saying anything in public that would prejudice the case. (Monson lost the case on appeal due to there being evidence that he had agreed to the effigies being made and only raised an objection when he discovered that they were being displayed in the chamber of horrors; however, the case did establish in English law the principle that libel did not just cover the written word but also extended to other forms of permanent expression including wax effigies.[29])

As we have seen, Morritt and Monson would eventually work together. However, before that, Morritt, undaunted by his failure to make use of Monson’s services as a lecturer, used the contacts he had established when negotiating with Monson to bring off an arguably much more substantial coup: bringing out from hiding the fugitive Scott/Sweeney.

“SCOTT” AS THE “MISSING MAN” At Morritt’s Entertainment Hall, Piccadilly, London, yesterday afternoon, Edward Sweeney or “Scott” of Ardlamont notoriety, appeared in what is described as ‘‘a sensational mystery entitled the missing man.” A framework is fixed on the stage, and “Scott” having been fastened with twine to a chair, the latter is raised in the air, and “Scott” suddenly disappears, the empty chair afterwards falling to the stage. No statement of any kind was made by “Scott”, though this had apparently been expected by some.[30]

In fact, as subsequent events would reveal, the Edinburgh police had already ended their search for ‘Scott’ in light of the verdict of the Monson trial. Thanks to his closeness to Monson’s legal team, Morritt was aware of this, but it was unknown to the public at large, hence the sensation that accompanied Scott’s appearance on the Princes’ Hall stage.[31] As ever, Morritt had read popular public taste correctly, and the illusion in its new form was a big hit, with Scott treated by audiences as something akin to a pantomime villain.

Charles Morritt, with his " Missing Man" illusion, is clever; Mr. Scott, the missing man, got a warm reception from the gods, they hissed him to their hearts' content, and inquired after Monson.[32]

It would later emerge that Morritt had promised a solicitor who had been in contact with Scott while he was on the run a fee in return for putting the two in contact. In a move typical of the man, Morritt had reneged on the deal once contact had been made. This led to a court case,[33] one of several that Morritt would face in a little over a year, the details of which reveal much about how Morritt did business.

The first occurred shortly after Morritt took over the running of a failing music hall on Shaftesbury Avenue called the Eden Theatre of Varieties. Morritt tried to turn the hall’s fortunes around by staging boxing matches at the Eden, hiring the then newly famous African American boxer Frank Craig, the ‘Harlem Coffee Cooler’, to appear nightly in an act that combined boxing exhibitions with a song and dance routine. I tell the story of Craig’s life and career elsewhere. Morritt also brought to the English stage a distasteful innovation from America: ‘battle royales’, mass brawls, usually involving men of colour hired off the street for the purpose.[34]

In order to make room for these boxing spectacles, Morritt culled several variety acts from the Eden bill, including acts contracted for return engagements. On 5 November 1894, one of those returning acts, Bessie Hinton, the ‘Coster Queen’, turned up at the Eden expecting to begin rehearsals only to be told her services were no longer required. Morritt offered Hinton £2 2s in compensation; Hinton, not unreasonably, demanded instead the £28 the full engagement would have paid (4 weeks at £7 a week). Nothing was resolved during this encounter, so Hinton went away and returned to the theatre that evening. On seeing her, Morritt seized hold of her and threw her into the street. Hinton filed a charge of assault. At the suggestion of the magistrate, the two came to a financial settlement.[35]

The other case that Morritt faced was also in relation to his tenancy of the Eden. In it, he was prosecuted for operating the theatre bar without a licence. Morritt’s unsuccessful defence was that he had sublet the running of the bar to another man, and it was, therefore, not his concern whether the bar was licenced or not. This case is of particular importance as it was during its proceedings that it was revealed that Morritt’s rescue plan for the Eden had failed, and this had led to a second bankruptcy case against him.[36]

It was Morritt’s attempts to settle the debts he had incurred as a result of his unsuccessful attempt to rescue the Eden that led him to abandon his elaborate and costly stage illusions in favour a much cheaper form of spectacle, one that would bring Alfred John Monson back into his life: stage hypnotism.

“When I was about to leave my somewhile associate, the boy on whom he practised his mesmeric tricks came to me and said, 'I wish you'd take me with you, and let me be your boy, Mr Morritt.' 'But,' I said. 'I'm not a mesmerist.' 'More ain't he,' said the lad. 'I'll learn you all his tricks, and you can do everything at me that he does.' I did not see my way to enter into this arrangement, but it showed me how much there is in mesmerism.”[37]

It is a measure of Morritt’s desperation that by the beginning of 1895, he had embraced a form of entertainment he himself had derided just two years earlier. However, it was also typical of the man that, when he went into it, he did it in a way that had never been attempted before, one designed to keep the public coming back night after night.

The Royal Aquarium was an entertainment complex, a kind of city centre Crystal Palace, that once occupied the site now occupied by Methodist Central Hall in Westminster. Charles and Ada/Lillian Morritt opened at the complex’s theatre in October 1894. Meanwhile, Morritt licensed some of his other routines, such as the Flying Lady, to other illusionists, including their actual inventor, Joseph Winson, who toured the country as the ‘Morritt and Winson Wonderland’.[38]

For the first four months of the Morritt’s engagement at the Royal Aquarium, they presented a stripped-down version of their regular ‘entertainment’, comprising the Convict’s Escape and Lillian Morritt’s lightning calculator routine. However, in February 1895, with court cases piling up, Morritt debuted a new, not coincidentally, much cheaper act, centred on putting volunteers into a trance, not for a few minutes, as with the usual mesmerism act, but for days at a time, creating the sensation known as the Long Trance.[39]

THE LONG TRANCE. For three days and three nights, Arthur Wootton has been lying motionless in a trance at the Royal Aquarium. This very curious experiment is attracting increasing attention on the part of medical men, who have during the past two or three days almost turned the Aquarium into an annexe of the Royal College of Surgeons.[40]

Over the course of the first few months of 1895, Morritt placed a number of people, men and women, into ‘trances’ designed to last for days, albeit with mixed success. To prove that his subjects were in suspended animation, Morritt nightly invited people to come up onto the stage and stick pins and needles into the fleshy parts of the subject's lips and top of the head; a spectacle that, evidently, went over very well. In response to claims in the press that this was ‘claptrap’, Morritt—who knew full well that it was exactly that, as he had made plain in the interview he gave back in 1893—countered that he was willing to have a limb amputated while in a trance to demonstrate that the effect was real—a typical bit of illusionist bluster.[41]

In May 1895, Morritt embarked on a tour with Monson as his mesmeric subject—which we will return to shortly—however, the long trance act continued at the Aquarium, now under a ‘Professor Fricker’ (licensed to him by Morritt?). Sceptics also continued to push back, one of whom, a ‘Professor Arthur Dale’ produced letters written by some of Morritt and Fricker’s subjects in which they admitted to the trick, writing that they had been taught to stay rigidly still even while being stuck with needles; meanwhile, once the theatre closed for the evening, they were free to rise from their ‘slumber’ and go out and about as normal, albeit in disguise.[42]

The public seemingly did not care, at least, not in great numbers: Morritt was to perform a version of the Long Trance for the next 30 years. But first, there was the return of Monson.

In the Operetta House, Edinburgh, last night, the great Ardlamont trial, which occupied the Lord Justice Clerk and a jury ten days, was retried by Mr Morritt, the hypnotiser, and Mr Monson in fifteen minutes.[43]

The challenge of the Long Trance as a routine was the expense and effort of finding and training suitable ‘sleepers’. Added to which, as Morritt had found out to his cost at the Aquarium, not every ‘subject’ proved capable of seeing the routine through. The appeal of the Monson act was its simplicity: all that was required of Monson as a subject was that he display no emotion while in the ‘trance’; Morritt took care of all the stage business connected to the act. Of course, it also required ignoring any ethical consideration connected to allowing a man whom many believed to be a murderer to make a case for his innocence while pretending to be in a trance.

Although presented to the public as if Monson had contacted Morritt by letter offering to be a subject, an offer Morritt had accepted live on stage, it was surprisingly well known that Monson was in fact under contract to Morritt, and the two men had travelled up to Edinburgh, where the act debuted, together (‘At a quarter to ten, Mr Monson, of Ardlamont fame, who, it ought to be mentioned, arrived with the same train in Edinburgh as did Mr Morritt and his “subject,” entered into and occupied a seat in the dress circle.’).[44] As with the utterances of the Long-Trance sceptics, the public, as Morritt undoubtedly surmised, did not seem to care. They simply enjoyed the spectacle, albeit not without demonstration.

While these questions were being put, a gentleman in the audience declared that the envelopes were transparent and that the hypnotist could read the contents, and in this way suggested to Monson what to say. Considerable interruption ensued, and a good deal of the hubbub was occasioned by one of Mr Morritt's own attendants, who seemed to be labouring under great excitement.[45]

In an interesting coincidence, May 1895 was also the month that the Claimant—tossed aside by Morritt a year earlier—admitted for the first time in print that he was in fact Arthur Orton, a claim he quickly retracted. He died three years later.[46]

The Monson–Morritt mesmerism act had a surprisingly short life: within a month of its debut, Morritt had to resort to turning Monson into a subject for a touring version of the Long Trance; and a month later, Morritt ended an engagement at a music hall in London early because the act was no longer drawing an audience.[47] However, it had done the job asked of it: in association with licensed versions of his (and Winson’s) illusions being toured by other performers and the continuing Long-Trance spectacle at the Royal Aquarium, it had restored Morritt’s fortunes at least to the degree that he could return to presenting on-stage illusions.

Monson, meanwhile, turned (returned?) to insurance fraud as a way of making his way in the world. Justice would finally catch up with him in 1898, when he was sentenced to five years’ hard labour after trying to collect on an insurance policy that he and his associates had fraudulently taken out on a man they knew to be dying. Monson’s fate on his eventual release is unknown.[48]

DISAPPEARING DONKEY. The very latest illusion at St. George’s Hall, introduced yesterday afternoon by Mr. Charles Morritt, is the spiriting into thin air of a donkey! The animal at first showed a marked dislike to the cabinet prepared for its premature vanishing, but it was eventually persuaded to enter. When the cabinet was opened the donkey had gone, greatly to the mystification of the audience.[49]

It is one of the paradoxes of Charles Morritt’s life that he debuted the illusion that, more than any other, was to live after him, long after his fame had faded. Taken up and reworked as the Disappearing Elephant trick by Harry Houdini, who was instructed in its performance by Morritt himself, the Disappearing Donkey trick was a masterwork in the use of lighting and mirrors to fool an audience into thinking they were seeing something they were not.[50]

Morritt debuted the trick in 1912, by which time, through a combination of addiction to alcohol and a simple matter of a change in public tastes, he had been reduced to a jobbing conjurer, one of hundreds on the British variety circuit. His slide into effective obscurity had begun with the tumultuous year of 1895, as he wrestled with bankruptcy and a growing addiction to alcohol. The early demise of his Monson mesmerism act left him a spent force in the capital, and he retreated to the provinces, taking a lease of the Empire Theatre of Varieties in Blackpool. Frank Broom was one of the acts he booked into the Empire. Then, in the summer of 1897, he and Ada headed to the Antipodes.[51]

The tour of Australia ended in the Spring of 1898, and with it, so did the marriage of Charles and Ada Morritt. By the summer of that year, Morritt had formed a new variety company and was back touring the English halls without his wife and performing partner of 18 years. Later accounts have presented this as Ada leaving Morritt due to his alcoholism and starting life anew as an artist in Brighton.[52] However, an account of a court action that Ada Morritt mounted against Charles Morritt in 1927, backed by census returns, tells a very different story. Morritt deserted Ada on their return from Australia, and Ada was forced to find work as a housekeeper. It took her nine years to catch up with him, by which time, he had acquired a new partner—romantic and professional. At that time, Morritt promised to send Ada a monthly allowance, a promise he, predictably, reneged on. By 1927, Ada was living in Newcastle, destitute and dependent on poor relief. Unreported at the time was that Charles Morritt had for some time living with another woman, Sarah Elizabeth ‘Bessie’ McIntire, whom, in his 1921 Census return, he had claimed was his wife.[53]

Morritt was ordered by the courts to pay Ada 30s a week. Ada Morritt died just three years later in Gateshead, aged 75.

NEEDLE IN CHEEK Described as a "hypnotist and magic worker," Charles Morritt, of Pembroke-road, Bristol, known as Professor Morritt," appeared at the Halifax Quarter Sessions yesterday. Mr. Streatfield, prosecuting, said Morritt was charged with obtaining various small sums from the audience of the Victoria Hall, Halifax, on two dates in October, when the proceeds of collections amounted to £11 and £8.[54]

Ada Morritt had been alerted to her errant husband’s whereabouts by a newspaper story published, she said, in September 1927, reporting that Morritt had begun to once more perform his Long Trance act.[55] The week that Ada’s court action came to court in Newcastle, Morritt was performing the act in Halifax. By what must be viewed as a remarkable coincidence, the Yorkshire police chose to send someone to view one of those performances. On testing to see if Morritt’s subject really was in a trance, the police officers, of course, discovered he was not. Somewhat remarkably, this led to Morritt being charged in Halifax with obtaining money by false pretences—just one week after the Newcastle court action ended.[56]

Stage magicians understandably sprang to Morritt’s defence, paying for his lawyers, and he was acquitted of the charges in January 1928. However, the two court actions coming so close together broke him, and he and Bessie retired to Morecambe, where Bessie supported the pair by performing as a fairground fortune-teller.[57]

Charles Morritt died in Morecambe in 1936.

Charles Morritt had a knack for giving the public what they wanted and putting over an illusion. However, he also never met a contract he wouldn’t break, never met a debt he wouldn’t default on, stole ideas when he couldn’t buy them, and treated marriage as an afterthought in his relationships with women.

It might be tempting to say that in all these things, he was simply a product of his times, no better or worse than any man in an age before workers’ rights, copyright laws, and no-fault divorces. However, this would be to ignore the fact that Morritt became one of the charlatans he himself had railed against and did so in a manner so cynical that it astonished even his contemporaries. He was, in short, a man with more demons than virtues, and the only surprising thing about the reckoning that he experienced in 1927 was that it had taken so long. But then, as he himself had once said, some people cannot see what is right in front of them.

But how about the doctors and the dons?—"The easiest people in the world to deceive, my dear sir. Why, I'd rather perform before a room full of scientific experts than any other kind of audience. The fact is, they look at you so intently that they see nothing at all”.[58]

Jamie Barras, October 2025.

Back to Staged Identities

Notes

[1] ‘Mr Monson Hypnotised in Edinburgh’, Paisley Daily Express, 1 May 1895.

[2] ‘The Varieties…, The Stage, 19 September 1884.

[3] Morritt’s version of his life story: ‘Magic and Illusion: The Mystery Man’, Stage, 30 March 1995. Secretary at a music hall: ‘A Modern Magician’, Era, 22 April 1893. City Varieties: https://leedsheritagetheatres.com/city-varieties-music-hall/, accessed 24 October 2025. The best account of Morritt’s life and career is that given by Jim Steinmeyer: Jim Steinmeyer, ‘Hiding the Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible’ (London: Arrow, 2005).

[4] Name and year of birth of Ada Howell, marriage to Charles Herbert Morritt: 27 April 1883, Saint Paul, Old, Ford; London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1940; Morritt clerk and living with Ada as man and wife: entry for Charles Morritt, Leeds district, 1881 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc (Operations), accessed 20 October 2025. Year of death for Ada Howell Morritt, search, Births, Marriages, and Deaths, ‘Adelaide Morritt’, Gateshead, 1930, https://www.freebmd2.org.uk/, accessed 24 October 2025.

[5] ‘Provincial Theatres’, Era, 10 October 1884. I tell the story of the Bohee brothers here: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-cuckoos-and-nightingales, accessed 26 October 2025.

[6] ‘Notices and Advertisements’, Era, 29 November 1884.

[7] I use the account here: https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/tichborne-case-victorian-melodrama, accessed 24 October 2025.

[8] The Claimant in New York, tending bar: ‘Personal’, Anglo-American Times, 23 September 1887.

[9] ‘Failure of a Music-Hall Licensee’, Leeds Mercury, 26 February 1886.

[10] Ebdell partnership dissolved: Public Notices, Leeds Mercury, 25 April 1885. Bankruptcy: see Note 8 above.

[11] See Note 3 above, first reference. Herrmann: ‘Magician Herrmann Dead’, New York Times, 18 December 1896. Robinson: Jim Steinmeyer, The Glorious Deception: The Double Life of William Robinson, aka Chung Ling Soo, the Marvelous Chinese Conjurer (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2006).

[12] ‘Provincial Theatres, Hull: Mechanics’, Era, 7 January 1888.

[13] It is worth noting here that Morritt would later claim to have first taken to the stage as a conjurer as early as 1876—see Note 3 above, first reference—however, in an interview he gave in 1893, he claimed to have mastered conjuring at an early age but only to have recently started to perform it on stage: see Note 3 above, second reference. It does seem likely that he practiced it as at least a private amusement before taking to the stage, given his demonstrable skill from his earliest days as a performer.

[14] ‘A Mysterious Couple’, Pittsburgh Post, 3 November 1888.

[15] K. Rein, “Mind Reading in Stage Magic: The “Second Sight” Illusion, Media, and Mediums”, communication +1. 4(1), 2015. doi: https://doi.org/10.7275/R50C4SPB

[16] ‘Egyptian Hall’, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 4 January 1890.

[17] Note 3 above, second reference.

[18] Touring England: ‘Provincial Theatres, Leicester: Paul’s Theatre of Varieties’, Era, 11 August 1888; ‘Middlesex Music Hall’, Era, 29 September 1888. Hired by Williams and travelling to America: see Note 13 above. In Philadelphia and ‘Anglo-American All-Star Company’: ‘Plays and Players’, Philadelphia Times, 4 November 1888. In Washington, DC: ‘Amusements: Kernan’s New Theater’, Washington Post, 11 December 1888. In Baltimore: ‘Kernan’s Monumental Theater’, Baltimore Sun, 21 December 1888. In New York: ‘Hyde and Behman’s Theater’, Brooklyn Eagle, 4 December 1888. In Williams’ company, Pittsburgh: advert for Harry Williams’ Academy, Pittsburgh Press, 23 December 1888.

[19] ‘Public Amusements: The New Star Music Hall’, Liverpool Mercury, 23 July 1889.

[20] https://geniimagazine.com/magicpedia/Maskelyne_and_Cooke, accessed 25 October 2025.

[21] Morritt co-creator: ‘Maskelyne and Cooke’s Latest’, Sporting Life, 30 September 1891. Lillian as Maskelyne’s assistant: ‘Mrs Charles Morritt…’¸Era, 3 January 1891; https://jimsteinmeyer.com/2023/10/30/what-we-hide-will-the-witch-and-the-watchman-from-the-stalls-part-two/, accessed 25 October 2025.

[22] The Morritts at Princes’ Hall: ‘Princes’ Hall’, London Daily Chronicle, 24 October 1892. FLYTO and Missing Lady illusions: ‘Mr Charles Morritt’s Entertainment’, Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, 31 December 1892. Chevalier Ernest Thom and the Chair of Khalif: https://www.themagicdetective.com/2020/01/, accessed 25 October 2025. Lillian Morritt solo billing: ‘Princes’ Hall Piccadilly’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 30 December 1892. ‘Lightning Calculator’: ‘Morritt’s Entertainment’, Era, 20 January 1894.

[23] ‘A New Illusion’: ‘Theatrical Patents’, Era, 21 February 1891. Morritt and Winson patents: ‘New Patents’, Music Hall and Theatrical Review, 2 December 1893. It should be remembered that patents are published one year after they are filed. Drawings from one of the Morritt–Winson patents: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/032119955/publication/GB189317429A?q=pn%3DGB189317429A, accessed 25 October 2025.

[24] Joseph Winson, ‘inventor and entertainer’, and Annie Winson, Croydon district, 1891 England Census; Joseph Winson, ‘member of entertainment’, and Annie Winson, Rickergate district, 1881 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc (Operations), accessed 20 October 2025. Winson ‘Gone’ illusion described: ‘Easter Monday Amusements: Crystal Palace’, Daily Telegraph & Courier (London), 19 April 1892. ‘Maid of the Moon’ model for Flying Lady: ‘North Country News’, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 25 March 1895. The Morritts perform the Flying Lady: ‘The Flying Lady’, Cheltenham Chronicle, 5 August 1893. Morritt and Winson’s Wonderland: ‘Amusements: Grand National Carnival’, Glasgow Evening Citizen, 9 June 1894.

[25] ‘Morritt’s Entertainment’, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 31 March 1894.

[26] ‘The Ardlamont Tragedy, Manchester Courier, 27 October 1893.

[27] I draw on this account of the Ardlamont Case: Hamish McPherson, ‘How Not Proven Verdict Played its Part in Controversial Trial’, https://www.thenational.scot/news/19309617.not-proven-played-part-controversial-trial/ and https://www.thenational.scot/news/19325937.not-proven-trial-served-inspiration-sherlock-holmes-books/, accessed 25 October 2025.

[28] ‘The Ardlamont Mystery’, London Daily Chronicle, 15 January 1894.

[29] https://www.lawteacher.net/cases/monson-v-tussauds.php, accessed 26 October 2025.

[30] ‘“Scott” as the “Missing Man”’, Edinburgh Evening News, 10 April 1894.

[31] ‘The Missing Scott Surrenders to the Police’, Lancashire Evening Post, 6 April 1894.

[32] ‘Glasgow: Scotia’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 1 June 1894.

[33] ‘Sequel to the Ardlamont Case’, Sheffield Evening Telegraph, 25 March 1895.

[34] Frank Craig: https://www.ishilearn.com/the-spectacle-the-cooler, accessed 26 October 2025. Battle royale: ‘Boxing at the Eden’, Morning Leader, 17 November 1894.

[35] ‘Police Courts: The Coster Queen’, Morning Leader, 17 November 1894; ‘Music-Hall Assault Case’, Sheffield Evening Telegraph, 28 January 1895.

[36] ‘Police Intelligence: Bow-street’, London Evening Standard, 3 May 1895.

[37] Note 3 above, second reference.

[38] Other illusionists performing the Flying Lady: ‘Blackpool: the Flying Lady’, Birmingham & Aston Chronicle, 27 July 1895. Morritt and Winson: Note 24 above, final reference.

[39] Royal Aquarium: http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/RoyalAquarium.htm, accessed 26 October 2025. The Morritts open at the Aquarium theatre: ‘A New Illusion at the Royal Aquarium’, Reynold’s Newspaper, 14 October 1894.

[40] ‘The Long Trance’, Guernsey Star, 9 February 1895.

[41] ‘The “Trance” at the Aquarium’, Morning Post, 12 February 1895.

[42] ‘Hypnotism: Is it a Pseudo-Science?’, South Wales Echo, 12 July 1895.

[43] ‘Ardlamont Case Retried: Monson and the Hypnotist’, North British Daily Mail, 1 May 1895.

[44] ‘Hypnotism at the Operetta House’, Edinburgh Evening News, 30 April 1895. Under contract for a tour: ‘Waiting for Monson’, Dundee Evening Telegraph, 25 May 1895.

[45] ‘Hypnotic Experiments at Edinburgh’, Perthshire Advertiser, 6 May 1895.

[46] ‘The Claimant’s Confession: He Admits He is Arthur Orton’, Bradford Daily Argus, 15 May 1895.

[47] ‘Hypnotic Experiments’, Star of Gwent, 28 June 1895; ‘Babble’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 5 July 1895.

[48] ‘The Monson Frauds: Verdict and Sentences’, Dundee Advertiser, 1 August 1898.

[49] ‘Disappearing Donkey, Daily Express, 17 August 1912.

[50] Victoria Moore, ‘The Yorkshire Man who Taught Houdini How to Make an Elephant Disappear’, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-471954/The-Yorkshire-man-taught-Houdini-make-elephant-disappear.html, accessed 26 October 2025.

[51] In Blackpool: ‘Blackpool’, Preston Herald, 1 April 1896. In Australia: ‘Amusements in Australia’, Era, 16 October 1897. Frank Broome (spelled ‘Broome’) at the Empire Blackpool: ‘Provincial Theatres’, Era, 12 September 1896. I tell Frank Broom’s story here: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-messrs-broom-and-carey, accessed 26 October 2025.

[52] See, for example: http://www.calderdalecompanion.co.uk/mmm167.html, accessed 26 October 2025.

[53] Court case: ‘Illusionist in Court’, Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 16 October 1927. In 1911, Adelaide Morritt was working as a housekeeper in Brierfield, Lancashire: census return for ‘Addalaide Morritt’, Brierfield district, 1911 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc (Operations), accessed 20 October 2025. Charles Morritt, ‘entertainer public’, and Elizabeth Morritt, 1921 Census, Darlington district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc (Operations), accessed 20 October 2025. Sarah Elisabeth ‘Bessie’ McIntire: See Note 50 above.

[54] ‘Needle in Cheek, Daily Mirror, 21 January 1928.

[55] This may actually have been an ad that Morritt placed in The Stage in August 1927 asking theatres interested in booking him to contact him at the Theatre Royal, Ledbury: ‘Wanted: Halls or Theatres…’, The Stage, 25 August 1927.

[56] ‘Tickled the Patient’, Aberdeen Press and Journal, 31 October 1927.

[57] ‘Hypnotist Acquitted’, Weekly Dispatch (London), 22 January 1928; ‘Fortune Tellers Fined’, Morecambe Guardian, 1 August 1930.

[58] Note 3 above, second reference.

The Long Trance. Illustrated Police News, 9 March 1895. Imaged created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

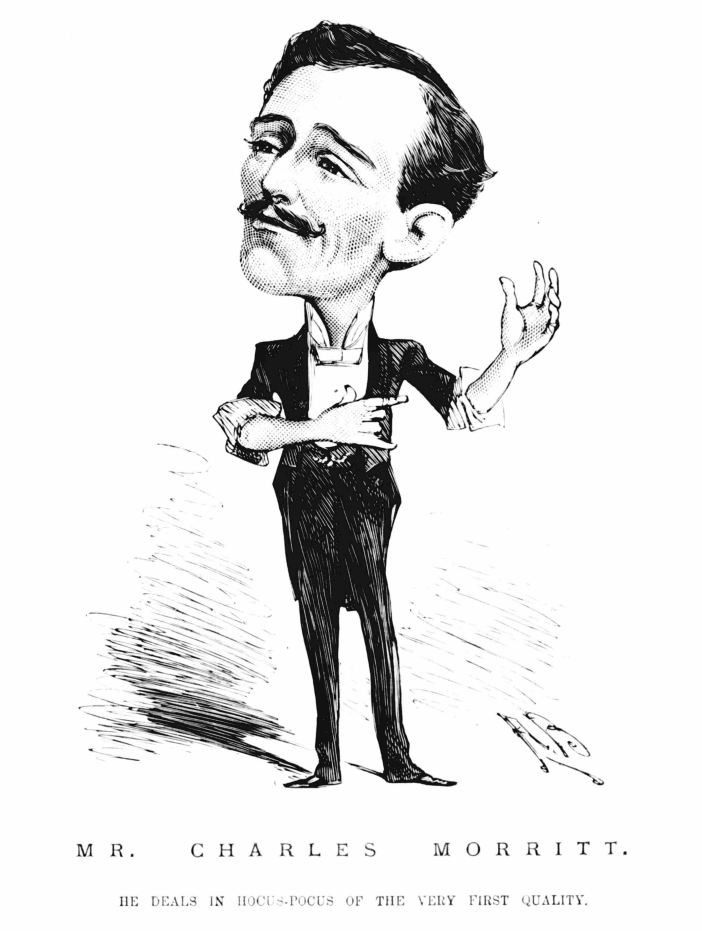

Charles Morritt. London and Provincial Entre'acte, 7 October 1893. Imaged created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Lillian Morritt, aka Ada, the wife of Charles Morritt, and a performer in her own right. Gentlewoman, 12 August 1893. Imaged created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Alfred John Monson. Pall Mall Bulletin, 14 September 1893. Imaged created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Edward Sweeney, aka Edward Scott. Illustrated Police Bulletin, 14 April 1894. Imaged created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

The Missing Man illusion, featuring 'Scott' tied to the chair. Penny Illustrated Paper, 14 April 1894. Imaged created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.