Bakeneko

Jamie Barras

Fuji-ko, the dainty Japanese actress who is now making a “hit” in the “White Chrysanthemum”, said that the Japanese are becoming so Western that they will probably soon learn to appreciate plays which last three instead of twelve or more hours. “I was so impressed by this tendency,” she said, “that I wrote a one-act version of the ‘Vampire Cat’, one of Japan’s oldest and most popular dramas. The play takes a day to perform, but I have taken the main incidents and reduced it to an hour’s performance. I hope to produce it in America”.[1]

The Vampire Cat of Nabeshima (鍋島化ばけ猫騒動 Nabeshima bakenekosōdō, literally: the Nabeshima Transformed Cat (‘bakeneko’) Incident) is one of the most famous ghost stories of Japan. In the form in which it reached the West, being published in English as early as 1871, it is the story of a Samurai Lord tormented by a cat spirit that takes the form of his favourite concubine and nightly robs him of a portion of his life force. He is saved by a loyal retainer who realises what is happening and confronts the cat spirit, forcing it to flee to the mountains, where it is hunted and killed.[2]

That the performer who called herself ‘Fuji-ko’ should feel drawn to a story of transformation and theft is telling. Although she variously presented herself as Japanese or Anglo-Japanese, raised in America or England or Japan, she was, as I will show here, in fact Florence Kent (1868–1912), a Canadian woman of Scottish descent who had no more knowledge of Japan than what she had read in books or seen on stage. To tell her story, we need to penetrate her disguise. But first, we need to set the scene.[3]

Mr Belasco’s Japanese Play. David Belasco will go to Washington this evening to confer with Ythguan Ynohtna, the stage manager of the Japanese troupe touring the company on its way to Paris for the exposition. Mr. Belasco will endeavor to arrange with Mr Ynotna to collaborate with him in the dramatization of John Luther Long’s Japanese story “Madame Butterfly”. He hopes to stage the play as a tragedy with a strictly Japanese atmosphere[…][4]

Fuji-ko first appeared in 1904. To understand the forces that brought her into being, we need to understand the American experience of Japanese culture in the first half of the first decade of the Twentieth Century. Although Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado had been a smash hit back in 1885 and was still playing all over North America two decades later, it was seen very much as a comedic fantasy with a Japanese setting, not an attempt at an authentic portrayal of Japanese life. The same could be said of Sydney Jones’ operetta, The Geisha, which debuted in New York in 1896. Indeed, a prominent Japanese writer active in this period, critical of Western representations of Japan on stage and in literature, excused both of these works on those grounds.[5]

Instead, the ‘real’ depictions of Japan in fiction and drama, at least as Western writers saw it, arrived in the form of John Luther Long’s collection of short stories that included ‘Madame Butterfly’, published in 1899. The following year, fully five years before Puccini turned the story into the famous opera, New York actor–writer–producer David Belasco collaborated with Long to produce a non-musical version for the stage—the work that inspired Puccini.[6]

When Long wrote the original short story, he was drawing on material sent to him by his sister, a Christian missionary in Japan, and, as the quote above shows, Belasco also sought Japanese inspiration for the dramatization in the form of the input of a member of a troupe of Japanese actors playing at a theatre in Washington, DC. This troupe was the Kawakami troupe, led by husband and wife ‘Otto’ and Sadayakko Kawakami (Otojirō Kawakami (川上音二郎, Kawakami Otojirō, 1864–1911) and Sadayakko Kawakami (川上貞奴, Kawakami Sadayakko, 1871–1946)).

Sadayakko Kawakami, who would become known to Western audiences as Sada Yacco, was a former Geisha who had played a purely behind-the-scenes role in the theatrical troupe that her husband ran before the troupe embarked on a tour of America in the summer of 1899. Otojirō Kawakami arrived in America with a high-minded mission to expose Western audiences to authentic Japanese kabuki drama and Japanese interpretations of the works of Shakespeare. However, in the event, both of these entertainments went down like a lead balloon, and by the time the troupe reached Chicago, the members were close to starving. It was there that Kawakami conceived the idea of taking the costumes and setting of one of the kabuki pieces and using these as the basis for a new piece, The Geisha and the Knight, that would be much more palatable to Western audiences in duration, structure, and acting style; a piece that, as the title suggests, had Sada Yacco at its centre. The gamble paid off, the troupe became a sensation, and Sada Yacco became the first internationally known Japanese actress. After repeating their American success at the 1900 Paris Exposition, the troupe returned to Japan. However, before that, while still in Paris, they met an American pioneer of modern dance, Loïe Fuller (1862–1928). Fuller brought the Kawakami troupe back to Europe the following year for an extended tour that lasted until 1903. During this second tour, Puccini saw Sada Yacco perform on several occasions and drew inspiration from the musical elements of her performance for some of the music for his opera treatment of Madame Butterfly. Thus, both stage versions of Madame Butterfly can be said to have drawn inspiration from the work of the Kawakami troupe.[7]

Nineteen Oh Three was also the year that Belasco and Long premiered their follow-up to their dramatised version of Madame Butterfly, a work called The Darling of the Gods. This new work retained the Japanese setting of Madame Butterfly but included only Japanese characters. This was another huge hit despite being what one London critic would later describe as ‘glorious claptrap’, a humourless potboiler that owed more to the Tales of the Arabian Nights than anything authentically Japanese.[8]

Shortly after its debut, The Darling of the Gods became embroiled in a lawsuit brought by Belasco against the author of a novel with a Japanese historical setting, ‘The Wooing of Wistaria’, published the year before. The author’s pen name was Onoto Watanna, and someone had expressed in print the view that the plot of The Darling of the Gods bore strong similarities to that of Watanna’s novel. As two theatrical producers, rivals of Belasco, named Klaw and Erlanger, were in the process of bringing one of Watanna’s earlier novels, The Japanese Nightingale, to the New York stage, and were keen to eliminate the competition that Darling of the Gods represented, Belasco took the view that Watanna was behind the libel and had her arrested. Ultimately, his suit was rejected on the grounds that, although the statement was libelous, there was no evidence that Watanna was behind its publication. The Japanese Nightingale eventually made it to the stage shortly after The Darling of the Gods ended its New York run. It was a disaster; the critics roasted it, and it closed early.[9]

This incident is of interest to us for a number of reasons. The first is that it demonstrates how much in vogue productions with a Japanese setting were in New York in the first half of the first decade of the Nineteenth Century.

The second is that the name of the heroine of ‘The Wooing of Wistaria’ is ‘the Lady Wistaria’ [sic], who is referred to variably as ‘Fuji-san’ or ‘Fuji-wara’ in the novel, ‘Fuji’ (藤) being the Japanese word for wisteria. Fuji-ko would later tell people that ‘the Lady Wisteria’ was the English translation of her name. It is clear from this that she took inspiration from Watanna’s 1902 novel in creating her fictional Japanese name. However, while ‘Fuji’ does mean wisteria, ‘ko’ (子) is simply an affectionate diminutive, and adding it to a name is akin to calling someone with the given name ‘Anne’, ‘Annie’, ‘Rose’, ‘Rosie’, etc., almost the opposite of the ‘Lady Wisteria’ meaning that Fuji-ko claimed for it. (‘Fuji-ko’ or ‘Fujiko’ as a name does not appear in this form in the Watanna novel.)

The third reason this incident is of interest to us is because of the identity of Onoto Watanna herself. ‘Onoto Watanna’ was the pen name of a woman who claimed that her real name was ‘Kitishima Tasha Hasche’ and she was of Anglo-Japanese heritage. She also, she said, had an English name, Winifred Eaton, and later was known in society by her married name, ‘Winnifred Babcock’. In fact, Winnifred Babcock (1875-1954) was a woman of Anglo-Chinese heritage whose only name at birth was Winnifred Eaton. When she became a writer, she adopted a false Japanese identity in part to escape the stigma attached in this period to being Chinese and in part to exploit for financial gain the rage for all things Japanese.[10]

In short, Fuji-ko, a woman who falsely claimed to be Japanese, had taken her name from a novel written by Onoto Watanna, another woman who falsely claimed to be Japanese. As Fuji-ko/Kent was almost certainly unaware of Watanna’s deception, this stands as simply an irony, one of several that pepper the Fuji-ko story.

EMPIRE–The Empire Theater offers a vaudeville bill this week of excellent talent. The engagement will open with a matinee tomorrow. Fuji-ko (Miss Florence Heathcote) is to present her Japanese playlet, “Yu-Me-Mo-Yo”. The piece was originally put on with considerable success at the Grand Central Palace, New York, for a Japanese war benefit. Fuji-ko is of Anglo-Japanese extraction, and the wife of an American.[11]

The name ‘Fuji-ko’, coupled with that of ‘Florence Heathcote’, first appeared in the US press in December 1904. However, looking back to the Spring of that year, we find an essay in a San Francisco newspaper written by one ‘Fiji-ko’, who is described as a ‘talented young Japanese playwright and entertainer’ who has ‘adopted the American name Florence Heathcote’—again, shades of the Onoto Watanna story, although Fuji-ko could not have known just how strong the similarity really was. This earlier journalistic piece is of particular interest as it is a discussion of theatre in Japan and includes the following description of themes in Japanese dramas.

In many of these dramas, the cat, the fox, and the badger feature largely. These animals are regarded with superstitious fear by Japanese people, who attribute to them the power of assuming the human form (that of a beautiful maiden is the one most often selected), in order to more readily accomplish their desires.[12]

The bakeneko story was already on Fuji-ko’s mind back in 1904. Separate from the Fuji-ko/Fiji-ko persona, we have evidence of someone calling herself Florence Heathcote performing Japanese songs, accompanying herself on the shamisen, in the New York area, going back to the beginning of 1903. It is interesting to note that in one of the reports, the writer went out of their way to report that one of the other women present was ‘born in Tokio’, but there is no mention of Florence Heathcote being Japanese; she is simply recorded as singing and playing Japanese songs and being ‘of New York’. Alas, the reports do not mention what language these ‘Japanese songs’ were sung in. However, we know that Heathcote/Fuji-ko’s drama ‘Yu-Me-Mo-Yo’ was performed in ‘quaint Japanese English’ and intelligible to the audience.[13]

It is worth noting that ‘Florence Heathcote’ was another borrowing from a popular novel of the period: ‘Florence Heathcote’ was the name of the heroine of ‘A Life’s Mistake’.[14] It is also worth noting that Fuji-ko would abandon this persona by the summer of 1905, and it was simply, solely, as ‘Fuji-ko’ that she would make the journey to London in July of that year.

ONE of the promised sensations of the early autumn in the music hall world will be the appearance under West-End management of Fuji-ko, the Japanese lady whose singing and dancing caused so much attention at the Actors' Orphanage Fund Fete, in the Botanic Gardens. Fuji-ko has come to London by way of America and speaks English with a charming foreign accent. She has made a good impression in the States and in the various English houses in which she has already appeared.[15]

Fuji-ko speaks English perfectly. She has spent nine years of her life in America and graduated at an American college.[16]

Fuji-ko spent the summer of 1905 recharting the course she had followed in America in 1903 and 1904: performing one-person shows at country houses and society events while trying to interest someone in producing her Russo-Japanese-War-themed playlet, retitled ‘Heart of Gold’, for the stage. Interestingly, there is no mention of an American husband. Her society appearances caught the attention of the weekly photo magazines, and in August 1905, The Sketch magazine published a photo spread of Fuji-ko in a kimono, posing as if dancing, and sitting eating, with her shamisen by her side.[17]

(Although I accept that this may reflect confirmation bias, with 100+ years of photographs and moving images of people of genuine Japanese heritage to call on for comparison, it is hard looking at these photographs today to understand how anyone seeing them could have believed that Fuji-ko was, as she claimed, Japanese, even allowing for the version of the story that she sometime told in which she described herself as Anglo-Japanese.)

Fuji-ko finally took to the London stage in October 1905. Coincidentally, a second Japanese drama was being performed elsewhere in London, this one by a genuine company of Japanese actors, the Arayama troupe.[18] To the amusement of the London press, this resulted in a further coincidence.

The long arm of coincidence has created a flutter of excitement among the Japanese actors in London. In the struggle for fame, two Japanese theatrical ladies have unknowingly chosen the same stage name, which is about as unfortunate, from a professional point of view, as two music-hall comedians singing the same song in separate turns. The two ladies have not yet come face-to-face. The name of each of the ladies is “Fuji-Ko,” which means the Lady Wisteria. One of them is performing in “Hara-Kiri,” the new Japanese drama; the other Fuji-Ko is a dainty actress who has not yet made her stage debut in Loudon.[19]

It is obvious from this clipping that the London press did not know that, contrary to what Fuji-ko had claimed, ‘Fuji-ko’ did not translate as ‘the Lady Wisteria’, the name of the heroine of Onoto Watanna/Winnifred Babcock’s 1902 novel. The Arayama troupe included three female performers: Haneka Fujiko, ‘Miss Miyako’, and ‘Miss Hanako’. Of interest to us here, ‘Miss Hanako’ was Hisa Ōta (大田ひさ, Ōta Hisa, 1868–1945), who would become better known in the West as Madame Hanako. Like Sada Yacco, a former Geisha, Hisa Ōta would, within a year, become another protégé of Loie Fuller. Fuller would try to turn her into a second Sada Yacco. However, Hanako would instead chart her own course, tending more towards comedy than the intense dramas for which Sada Yacco was famous.[20]

Also of interest to us, Fuji-ko’s playlet included painted scenery, the designs for which were provided by Yoshio Markino (牧野 義雄, Makino Yoshio, 1869–1956), a long-term Japanese resident of London.[21] As I have written elsewhere, Markino was an artist and scenic designer who was often called upon by West End producers to add a gloss of authenticity to Japanese-themed productions, which included providing designs for the 1904 London production of Belasco and Long’s Darling of the Gods.[22]

Thus, Markino was no stranger to seeing people of European descent in ‘yellowface’ make-up take to the London stage. However, it is curious that he would lend his support to someone who was playing the part off stage as well as on—he surely could not have been fooled by Fuji-ko’s act. This said, it seems possible that he had no direct contact with Fuji-ko, as we are told that the scenery was painted by scenic artist W.T. Hemsley to designs by Markino, and it may be that it was Hemsley with whom Markino interacted.[23]

CRITERION THEATRE. Although it has had to contend with musical pieces produced on a larger scale and on a larger stage, that charming little musical play, the "White Chrysanthemum," which was produced at the Criterion Theatre in August last, has achieved a notable success. Last night, Act I. was strengthened by a new duet for Mr. Lawrence Grossmith and Mr. Morand, Act II. by a valse song for Miss Isabel Jay and a new finale, and Act III. by a Japanese song and dance by a Japanese lady, Miss Fuji-Ko.[24]

Fuji-ko began 1906 performing a routine in ‘The White Chrysanthemum’, a book musical with a Japanese setting that had been playing at the Criterion since the middle of the previous year. She was not part of the plot but merely an additional entertainment, added, along with other changes, to refresh the production for the new year. The plot of ‘The White Chrysanthemum’ concerns an English woman who runs away to Japan to join her Royal Navy lover. With the help of her lover and her lover’s Chinese servant (why Chinese?), she disguises herself as a young Japanese woman, ‘O San’, the ‘White Chrysanthemum’ of the title, to escape discovery by the detectives that her father has dispatched to Japan to bring her home. Much hilarity ensues. The idea of a woman of European heritage who was pretending to be Japanese being brought into the cast of a musical about a woman of European heritage pretending to be Japanese to lend the production an air of authenticity is the definition of dramatic irony. It is perhaps no surprise that the attempt to refresh the production failed; the musical closed less than a month after Fuji-ko joined the cast.[25]

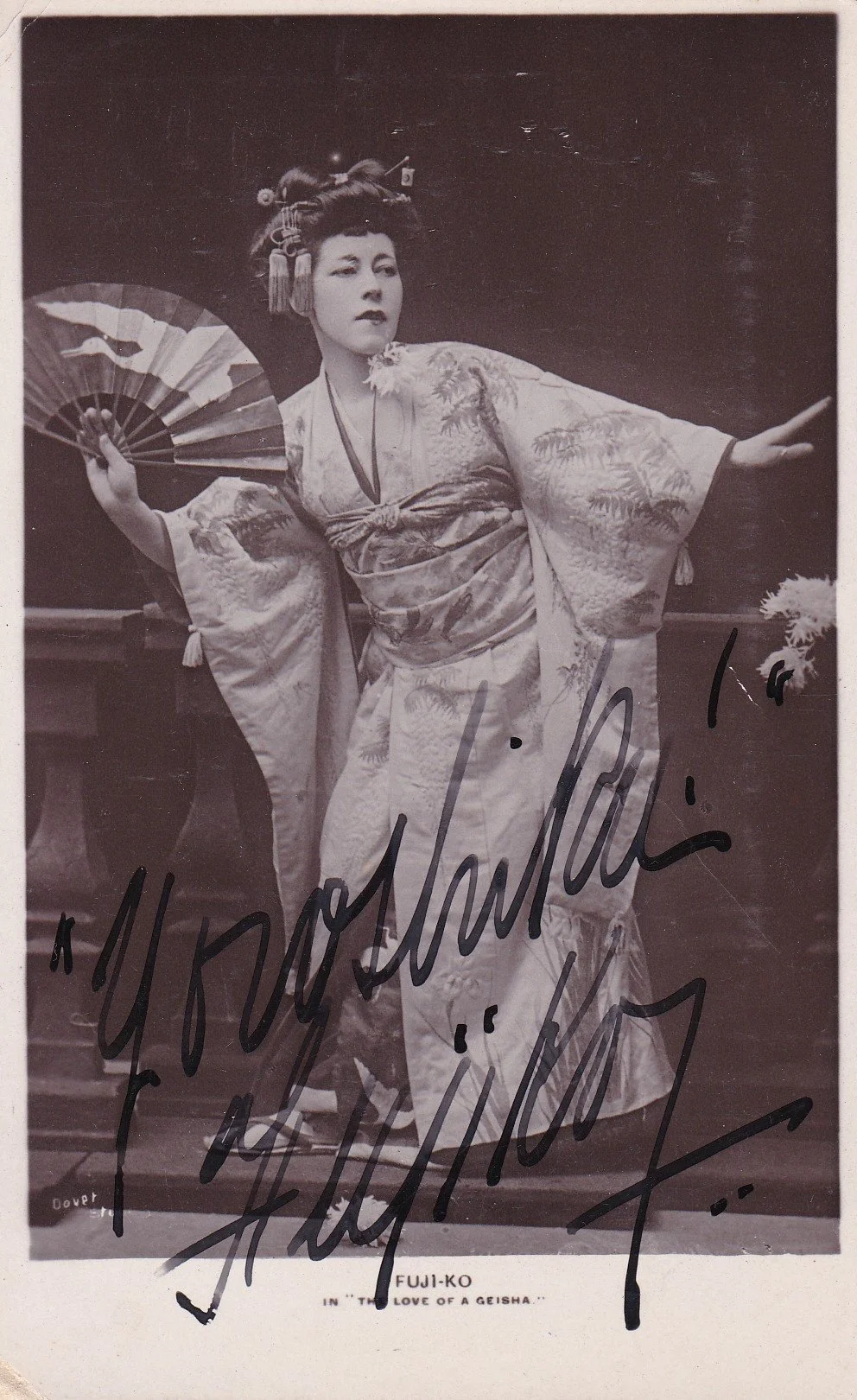

As we will see, this would not be the last time that Fuji-ko would be incorrectly cast in an existing Japanese-set entertainment to lend the production an air of authenticity. The late Spring of 1906, however, would see Fuji-ko back on stage in one of her own productions, this time, a drama without words called ‘The Love of a Geisha’, again, with designs by Markino.[26]

The production photographs taken for this piece would be used by Fuji-ko as her promotional material for the rest of her theatrical career. They would even find their way onto postcards, one of which is reproduced in the gallery at the bottom of this article—a rare colour image of Fuji-ko. (Again, it is hard to see how anyone seeing these photographs would have believed that this was a woman of East Asian heritage.) Meanwhile, the play’s description affords us an insight into the seriousness with which Fuji-ko approached her art and her artifice. No, Mikado or Darling of the Gods—Arabian Nights fantasies with Japanese set dressing—this was a piece that claimed to spring from Buddhist theology.

Fuji-Ko, the well-known Japanese actress, who is now in London has written and will ‘shortly perform a one-act “dream play,” the main feature of which is an extraordinary series of illusions or visions. The theme of the play is the doctrine of “nirvana,” believed in by Buddhists and Brahmins. According to this doctrine, the soul, after death, and after passing through a variety of phases, finally becomes “nirvana,” or the “drop in the ocean”; that is, it loses all individuality and becomes extinct. The process by which the state of nirvana is arrived at is called dhyana, and is simply a series of ecstasies or trances self-imposed.[27]

What do works like The Love of the Geisha and Fuji-ko’s later one-act version of the tale of the vampire cat of Nabeshima tell us about how much Fuji-ko had invested in her fake Japanese identity? It seems to me that they are open to two very different possible interpretations. The first is that Fuji-ko had a greater investment in her fake Japanese identity than merely exploiting a rage for all things Japanese for profit, one that arose from an affinity with Japanese culture and beliefs that went beyond mere mimicry. The second is that she chose works without dialogue to avoid having to explain why, unlike, for example, the Kawakami and Arayama troupes, she did not present her works in the ‘original’ Japanese. It is possible, of course, that both explanations apply.

Whatever Fuji-ko’s reasons were for writing The Love of a Geisha, it was to prove the last London production in which she would appear. Although slated to perform the piece a second time later in the summer, instead, she suddenly returned to the US.

From New York we learn that Fuji-Ko, the Japanese actress, has arrived there two months ahead of schedule time. According to her manager, she left London literally at an hour's notice. She was rehearsing at the Empire in London, preparatory to her appearance there, when she learned of the serious illness of a friend in New York. She had just time to dispatch a dozen telegrams and reach a boat. Such disregard of business interest shows the strength of the Japanese character. Fuji Ko will remain here until the fall now, and before her return to Europe will be seen in her one-act play, The Love of a Geisha, which is said to be an embodied idea of the doctrine of Nirvana, an idea never before seen in the Western world.[28]

Fuji-ko would never return to England. Is it too much to suspect that she had fled because the game was up? Alas, we cannot know the real reason (although I will speculate on one at the end of this piece). This journey does at least provide us with a rare example of Fuji-ko’s name appearing in official records. This is in the form of entries in the passenger lists for the SS Minnehaha, which left London on 13 July 1906 and arrived in New York 11 days later. In both the London and New York records, she is listed simply as Fuji-ko—no surname—Japanese, and an actress. The New York arrival lists give her age as 27. If nothing else, these lists demonstrate the degree of commitment that Fuji-ko had to her assumed identity. At the same time, we might also wonder why, if, as she sometimes claimed, she was married to an American, she gave her nationality as Japanese and did not have a surname.[29]

Fuji-ko, the beautiful Japanese actress who recently arrived in this country, has been engaged to assist in an advisory capacity for Henry W. Savage’s production of Puccini’s “Madame Butterfly”.[30]

It is obvious from reports in US newspapers in the Spring of 1906 that this return to America was always planned, although it was not intended to be so soon.[31] While she, once more, searched for someone to bring her own productions to the stage, she busied herself providing spurious advice on the ‘real’ Japan to the first American production of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, an English-language version presented by Henry Wilson Savage. (It has to be acknowledged here that, just because the report of Fuji-ko’s involvement appeared in the US press, it does not make it true.) She also found the time to present her views on why the beauty of Japanese women was superior to that of American women.

The beauty of the Japanese woman is that of a grown-up child. There is nothing artificial about it. Here comes in the mental element, too. The mind of the Japanese is like a child in that it is always happy and bright.[…] The trouble with American women is that they are so seldom children, even when they are mere infants. The American woman is always talking about her troubles. If she is in pain, she wants every one to know it. The Japanese woman has behind her centuries of reserve, which have schooled her in the knowledge of the fact that the more you give voice to an ill the more you suffer.[32]

Let us be generous and say that these views speak of a woman who had known pain in her life and had chosen to escape into fantasy.

Fuji-ko was able to perform her Love of the Geisha at a special one-off performance at the Garden Theatre in New York in November 1906. It did not go well, with the reviewer for the New York Times calling her performance ‘colorless, insipid, and uninteresting’.[33] Faced with this disappointment, Fuji-ko fell back on her usual standby formula of performing Japanese dances at society events and appearing in existing Japanese-themed entertainments. It was announced that she would be joining the cast of a touring production of ‘The White Chrysanthemum’, the book musical in which she had appeared in London, although she did not in the end join the production. Instead, she opted for a supporting role in a much older Japanese-themed entertainment.[34]

The management of the Auditorium Opera Company says it is going to spring a surprise at the Auditorium this week by introducing to the music-loving public a real, live Japanese actress named Miss Fuji-ko in the role of Pitti-Sing in “The Mikado”.[35]

Starting in the summer of 1907, Fuji-ko would play Pitt-Sing in productions of The Mikado across America for the next two years. It was arguably the source of much of her income as an actress. It also brought her even more press attention. In interviews she gave in connection to The Mikado, she presented the latest version of her life story, a reversal of the story she told in England, with a life in America followed by a trip to England, replaced with a life in England followed by a trip to America.

I was educated in England, I am a college woman and I went to school there for many years. Then I decided to go on the stage and all last season I played at Sir Charles Wyndham’s theater in London, doing Japanese songs and dances and accompanying myself on the samisen. My success there led me to come over here.[36]

She also elaborated on her [fictional] early life.

When I was born in Japan[..] the English people and the Japanese people did not mingle as they now do[…] My mother brought me up just like a little Japanese girl—until she died. Then I must go to England. So to England I went and there I attended what I think you would call a girls’ college.[37]

Wherever she was, she would claim to be from somewhere else, always distancing herself from the society in which she found herself. Again, if we wanted to look into the psychology of this, we might suppose that this was a woman who had been hurt by society and found safety in keeping separate from it.

The main result of her success in productions of The Mikado, from her point of view, was that it gave her the exposure she needed to finally be able to mount the production that she had been working on for at least four years.

‘The Vampire Cat’, a legend of old Japan, told in a pantomimic dance full of the mysticism of the Far East, showing the temporary triumph of a beautiful evil spirit, of Nature’s revolt at overpowering malevolence, with a wider scope of terpsichorean expression that has yet been attempted, will be given its initial performance on Thursday evening, Nov. 12, at the German Theatre by Fuji-Ko, a Japanese actress and dancer of exquisite figure.[38]

Fuji-ko’s self-penned The Vampire Cat debuted at the German Theatre in New York in November 1908. Reviews of the piece, which were generally favorable, make plain that this was the version of the Vampire Cat of Nabeshima story published in English by Mitford in 1871, with Fuji-ko taking the role of the bakeneko that assumes the form of the favourite of a Samurai lord to gain access to his chambers. There, she sheds her kimono to perform a sensuous dance clad in a costume described as being ‘half-transparent, of iridescent colors, with a weird headgear, metal belt and hangings such as the demons and genii of Japanese fairy tales are supposed to wear’. In a departure from the written text, rather than being exposed, at the end of the dance, the bakeneko, its thirst sated, simply returns to the mountains.[39]

Among the few unfavourable, or, perhaps, cynical would be a better word, reviews, is one in which the reviewer was curiously focused more on Fuji-ko’s appearance than her performance.

[…]the woman looked less like a geisha than a mother of geishas[…]A thrill went through me when, stretching out her fingers hooked like claws, treading on bare feet noiseless as paws and with a sudden facial change from a siren’s wiles to a beast’s ferocity, she bounded on the prostrate man. Oh, why was it that I couldn’t let it go at that? But, no, I had to think how funny it would be if the whole weight of heavy Mrs. Fuji-Ko should land plum on the war-lord and force a big grunt out of him! Fat is so hard on fancy.[40]

Although rife with the misogyny and ageism with which actresses even today have to contend, the piece does point to a truth that Fuji-ko was finding it increasingly difficult to hide: she was far older than she pretended. And if that much about her was a lie, how much else was?

Although the November 1908 production of The Vampire Cat was a professional and personal triumph for Fuji-ko, it also marked the effective end of her performance of self-penned works. She would continue performing until the end of her life—just four short years into the future—but increasingly, simply as a vaudeville act and a speciality performer at society events and charity functions. We also see an increasing variation in her act with the introduction of, somewhat improbably, impersonations of stars of English music hall and American vaudeville (Anna Held, Harry Lauder, Vesta Victoria, and others), which she performed in an ‘amazing cockney dialect and Scotch burr’ as required.[41] What audiences made of a performer who professed to be Japanese, first performing Japanese dances and songs and then suddenly switching to speaking perfect English with regional accents is hard to fathom.

By the summer of 1912, although Fuji-ko was still living in the New York area and still presenting herself as Anglo-Japanese, there was a shift in her fabricated life story that, as we will see, moved it closer to the truth.

A young woman who is half Japanese, half English, who was born in Nova Scotia, educated on her travels, has taught in Jersey City, acted in London, visited Japan and entertained the exclusive ones of society in New York, might be expected to have something of an international flavour.[42]

The items that catch the eye here are the references to being born in Nova Scotia and having taught in Jersey City; these are both new and both unexpected, departing markedly from previous accounts, which had centred, in some way, on Fuji-ko being born in Japan and a student in New York or England. In searching for a reason for this shift, we need look no further than the next move that Fuji-ko would make, which was [back] to Nova Scotia. She would, at the same time, for the first time, make public her married name. However, more than this, she would at last abandon the pretence that she was Japanese.

A GREAT LONDON FAVORITE WILL APPEAR IN HALIFAX SOON. Mrs. D. Bowen Cooke well known in London and New York by the picturesque name “Fuji-Ko” which is Japanese for “The Lady of the Wisterias” who gives a recital here next month, is known as a remarkably clever actress and impersonator. Her study of an impersonation of the dainty little Japanese ladies is so remarkable that she has in a way become almost identified with the land that lies “East of he Sun” and “West of the Moon” and it is only when one sees Mrs. Cooke in regulation evening dress, give other “imitations” that one realizes her extreme versatility.[43]

‘Almost identified with’ implies that the only reason people thought that Fuji-ko was Japanese because she was so good at playing Japanese. No, people thought she was Japanese because, for nearly a decade, she had told people that she was. It is hard to know for certain why, after all this time, she had abandoned the pretence. We can speculate that the move back to Canada represented a new start. It may also be the case that, as the caustic 1908 review of her performance in The Vampire Cat crudely implied, her age and body shape no longer fitted the image of Japanese women that Western audiences had. Of course, these two things may have been connected.

There was, however, at least one further force at work: she was ill, although it is not clear if the cause had been diagnosed, or she realised just how serious it was. She almost certainly had no idea that, within a few weeks of her return to her home province, she would be dead.

Mrs. D. Bowen Cooke of Glace Bay died very suddenly at that place last week from an internal hemorrhage.[44]

SUDDEN DEATH AT GLACE BAY. Special to the Standard. Halifax, Dec. 1—The death has occurred suddenly at Glace Bay, N.S., of Fupko [sic], a Japanese impersonator. She hails from New York, but is a native of Nova Scotia, her name being Mrs. D. Bowen Cooke.[45]

In death, Fuji-ko finally gave up the secrets she had kept while she was alive. Glace Bay was, and still is, a small town on Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. In November 1912, only one death was registered there of a woman with the surname ‘Cook(e)’ who had died of internal haemorrhage: Florence Cook, wife of Dan Cook, cause of death: ‘gastric rupture’. The record of her death also lists her age, 42, and her place of birth: Tatamagouche (Nova Scotia). The woman who pretended to be Japanese but wasn’t was born in a town with a name that sounded Japanese but wasn’t.[46]

Tatamagouche is an even smaller community than Glace Bay. There were only a handful of infants with the given name ‘Florence’ recorded as living there in the 1871 Canada Census. Only one of those infants grew up to marry a man named Daniel Cook in New York on 7 June 1902.[47]

Florence Catherine Kent (1868-1912) was born in Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia, on 14 April 1868, the daughter of Edward Blanchard Kent, a shipbuilder, and his wife Jessie Kent née Williamson. She was Anglo-Scottish, not Anglo-Japanese. It is noticeable that her initials, FK, are the same as the name she adopted the way that she presented that name, Fuji-ko: F-K. Tragedy entered Florence’s life early, as her father died when she was only two, leaving her mother, Jessie Kent, to raise six children alone. The 1881 Canada Census found Florence at home with her widowed mother and siblings in the boarding house that her mother kept. However, there is then a 21-year gap in the records until the registration of her marriage to Daniel Cook in 1902.[48]

We can speculate that Florence spent at least some of those 21 years teaching in Jersey City. This is because 1) this detail is from the same version of Fuji-ko’s fabricated life story that truthfully records her place of birth as Nova Scotia and, like that latter detail, stands out as going against the other things she had claimed about her life; 2) she was, for all her faults, clearly an intelligent, well-read woman; indeed, a woman who loved reading; and 3) she was still single when she married Daniel Cook, though aged 34—working as a teacher was one of the few respectable ways for a single woman to make her way in the world.

Following a similar logic, it seems reasonable to suppose that she moved to the US from Nova Scotia in around 1896, in line with her 1905 claim that she had been in America for nine years. However, I acknowledge that this part of her life requires further research. One thing that is clear is that she was nearly a decade older than she claimed Fuji-ko to be. She was 40 the year that the reviewer of The Vampire Cat had so much to say about her appearance.

As for Daniel Cook, her husband of ten years, he was born in Lakeville, Connecticut, where his parents continued to live, and Bowen was indeed his middle name. Beyond that, all I have been able to find out about him is that, by 1917, he was working in Atlantic City, Georgia, as a salesman for a chemical company.[49]

Why Daniel Cook did not feature in any report of Florence/Fuji-ko’s time in England, I do not know. He was not a passenger on the ship that carried Florence/Fuji-ko back to New York in the summer of 1906, suggesting strongly that he did not travel with her to England in the first place. Indeed, we can speculate that the ‘friend’ of Florence/Fuji-ko’s whose sudden illness prompted her equally sudden return to the US was, in fact, Daniel Cook, her husband.

The greatest mystery, of course, is why Florence Catherine Kent spent nearly a decade pretending to be a Japanese woman named ‘Fuji-ko’. Alas, on that subject, I can again only speculate. It could be as simple as the reason that Fuji-ko’s contemporary, Chung Ling Soo, real name, William Robertson, pretended to be Chinese off stage as well as on: simply to help put over the act she performed on stage.[50] However, Florence/Fuji-ko’s immersion into Japanese culture was far deeper than Robertson/Chung Ling Soo’s immersion into Chinese culture, which was non-existent beyond the costuming. In that light, and recalling the comments Florence/Fuji-ko made about the differences between Japanese and American women, I wonder if Florence Kent was someone who found in this fantasy of being a woman happy by nature a refuge from the pain of the memories of the hardships she had suffered as one of six children of a widowed boarding-house keeper. I wonder if the origins of her life as a woman who claimed to be Japanese but was not was the life she had led in Tatamagouche, the town with the name that sounds Japanese but is not.

Jamie Barras, December 2025.

Back to Staged Identities

Notes

[1] ‘New Plays for Old: Japan Adopting Western Tragedies’, Daily Express, 23 January 1906.

[2] Chris Kincaid, ‘The Vampire Cat of Nabeshima’, https://www.japanpowered.com/folklore-and-urban-legends/the-vampire-cat-of-nabeshima, accessed 2 December 2025. The story is contained in ‘Tales of Old Japan’ by A. B. Mitford (Baron Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford Redesdale): https://archive.org/details/talesofoldjapan00rede_0/mode/2up, accessed 2 December 2025.

[3] The place and year of birth and year of death of Florence Cook are taken from the registration of her death: "Canada, Nova Scotia, Deaths, 1890-1955", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QK9SCGV5), Entry for Florence Cook and Dan Cook, 28 Nov 1912, accessed 2 December 2025.

[4] ‘Mr Belasco’s Japanese Play’, New York Times, 7 February 1900.

[5] Yone Noguchi, ‘Onoto Watanna and her Japanese Work’, Taiyo, 1907, 13:8, 18-21 and 13:10, 19-21. Available to read in English here: https://www.botchanmedia.com/YN/articles/Watanna-Taiyou.htm, accessed 2 July 2025.

[6] Arthur Groos, ‘Cio-Cio-San and Sadayakko: Japanese Music-Theater in Madama Butterfly’, Monumenta Nipponica, 1999, 54, 41–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2668273.

[7] Shelley C. Berg, ‘Sada Yacco in London and Paris, 1900: Le Rêve Réalisé’, Dance Chronicle, 1995, 18, 343–404. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1567837.

[8] Lydia Edwards. "A Tale of Three Designers: The Mystery of Design Attribution in Belasco and Long’s The Darling of the Gods Staged at His Majesty’s Theatre, London, in 1903." Theatre Notebook, 2015, 69, 97-112. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/636742.

[9] This incident is recounted in detail in a biography of Watanna: Dianna Burchill, ‘Onoto Watanna: the Story of Winnifred Eaton’ (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 79–84.

[10] See Note 9 above.

[11] ‘The Stage: Empire’, Pittsburgh Press, 4 December 1904.

[12] ‘The Queer and Quaint Japanese Theater’, San Francisco Chronicle, 24 April 1904.

[13] ‘Miss Campbell in a Runaway’, Brooklyn Daily Times, 21 February 1903; ‘A large audience filled the assembly rooms…’, Brooklyn Eagle, 23 April 1904; ‘Gen. Wheeler Honored’, New-York Tribune, 13 September 1903. ‘Quant Japanese English’: See Note 11 above.

[14] Charles Garvice, ‘A Life’s Mistake, or Love’s Forgiveness’ (New York: A L Burt Company, 1892).

[15] ‘Miscellaneous’, London and China Telegraph, 14 August 1905.

[16] ‘Visions of the Dead’, Daily Express, 4 May 1906.

[17] ‘Miscellaneous’, London and China Telegraph, 17 July 1905; ‘Her Husband’s Spirit: Japanese Dream Play for London’, Daily Express, 14 August 1905; ‘Miscellaneous’, London and China Telegraph, 27 October 1905. Photo spread: ‘A Japanese Actress Who Is to Play in English’, The Sketch, 24 August 1905.

[18] ‘Savoy Theatre: A Japanese Drama’, Daily Telegraph & Courier (London), 4 October 1905.

[19] ‘Strange Theatrical Coincidence’, Daily News (London), 4 October 1905.

[20] Female members of the Arayama troupe: ‘Public Amusements: Savoy Theatre’, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, 8 October 1905. Hanako and Loie Fuller: Nicola Savarese and Richard Fowler. “A Portrait of Hanako.” Asian Theatre Journal, 1988, 5, no. 1, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/1124024.

[21] See Note 17 above, final reference.

[22] https://www.ishilearn.com/nile-voyagers-darling-of-the-gods, accessed 4 December 2025.

[23] See Note 17 above, second reference. It should be said that the name given in the report is ‘Arthur Hemsley’, not W.T. Hemsley; however, this is in the form of a quote from Fuji-ko, so the error may have been hers.

[24] ‘Criterion Theatre’, Globe, 4 January 1906.

[25] https://web.archive.org/web/20230909093419/http://www.stagebeauty.net/produce/whitec/th-whitec.html, accessed 4 December 2025.

[26] See Note 16 above.

[27] See Note 24 above.

[28] See Note 24 above.

[29] Entry for ‘Fugiko’ in passenger lists for SS Minnehaha, left London 14 July 1906, UK and Ireland, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890–1960; entry for ‘Fujiko’, passenger lists for SS Minnehaha, arrived 24 July 1906, New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 2 December 2025.

[30] See Note 24 above.

[31] ‘Notes of the Stage’, Brooklyn Citizen, 30 September 1906.

[32] ‘Why So Many American Women Are Not Beautiful’, News Tribune (Tacoma, WA), 6 October 1906.

[33] ‘A Japanese Dream Play’, New York Times, 27 November 1906.

[34] ‘Concert for Ecole Maternelle’, New York Herald, 14 April 1907; ‘Plays & Players’, Chicago Tribune, 24 March 1907.

[35] ‘‘Mikado’ with Jap Actress’, Baltimore Sun, 19 May 1907.

[36] ‘Poli’s New Theater’, Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, CONN), 3 June 1907.

[37] ‘Fuji-ko, the Little Lady of the Wistarias’, New York Times, 10 May 1908.

[38] ‘Manhattan Stage Notes’, Brooklyn Citizen, 7 November 1908.

[39] ‘Manhattan Stage Notes’, Brooklyn Citizen, 11 November 1908; ‘Manhattan Stage Notes’, Brooklyn Citizen, 15 November 1908; ‘Japanese Actress Pleases’, New York Times, 13 November 1908.

[40] ‘A Japanese Actress’, Atlanta Journal, 22 November 1908.

[41] ‘Theatrical Attractions in the Metropolis’, Buffalo Sunday Morning News, 6 June 1909; ‘Rialto Gossip’, Cincinnati Enquirer, 16 May 1909.

[42] ‘Fuji-ko Entertains’, New York Tribune, 1 May 1912.

[43] ‘A Great London Favorite Will Appear in Halifax Soon’, Evening Mail (Halifax, Nova Scotia), 15 October 1912.

[44] ‘News From the Old Home Land For Maritime Provincialists’, Saskatoon Daily Star, 9 December 1912.

[45] ‘A Great London Favorite Will Appear in Halifax Soon’, Evening Mail (Halifax, Nova Scotia), 15 October 1912.

[46] Death Registration: "Canada, Nova Scotia, Deaths, 1890-1955", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QK9S-CGV5), Entry for Florence Cook and Dan Cook, 28 Nov 1912, accessed 5 December 2025. ‘Tatamagouche’ is derived from a Mi’kmaq word meaning the meeting of the waters: https://tatamagouchebrewster.wordpress.com/2013/09/30/tatamagouche/, accessed 5 December 2025.

[47] Entry for Florence Kent, 1871 Canada Census, Tatamagouche [sic] district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations); marriage registration: "New York, New York City Marriage Records, 1829-1938", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:24SR5BY), Entry for Daniel Cook and Florence Kent, 7 Jun 1902, accessed 4 December 2025. The entry records Florence Kent’s place of birth as ‘Tattamagouche, Nova Scotia’, confirming the identification.

[48] "Canada, Nova Scotia, Births, 1864-1877", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:W7FG-52N2), Entry for Florence Catherine Kent and Edward Kent, 14 Apr 1868, accessed 4 December 2025; entry for Florence Kent, 1881 Canada Census, Tatamagouche [sic] district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 4 December 2025.

[49] This information is contained on Daniel Cook’s registration for the US Draft: "United States, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KZZ3-FBP), Entry for Daniel Bowen Cook, from 1917 to 1918, accessed 5 December 2025.

[50] Lyn Gardiner, ‘How Not to Catch a Bullet, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2006/jun/09/classicalmusicandopera1, accessed 20 November 2025. Robinson/Chung Ling Soo famously died on stage in 1918 while performing the ‘catch the bullet’ trick.

Fuji-ko (Florence Kent). Postcard, author's own collection.

A. B. Mitford's Tales of Old Japan, the book that introduced the tale of the Vampire Cat of Nabeshima to Western audiences. Public domain.

The Vampire Cat of Nabeshima, Mitford's Tales of Old Japan, 1902 edition. Public domain.

Ume no Haru Gojūsantsugi (梅初春五十三駅), Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Public domain.

The Mikado, 1885. Public domain.

The Geisha, 1896. Public domain.

Sada Yacco (Sadayakko Kawakami). Postcard, author's own collection.

Hanako and the other performers of the Arayama Troupe in London. Ladies' Field, 14 October 1905. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Madame Hanako in London, 1905. Postcard, author's own collection.

The White Chrysanthemum, Criterion Theatre, 1905. Postcard, author's own collection.

Winnifred Eaton Babcock, pen name Onoto Watanna. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. "Onoto Watanna. Author of "Daughters of Nijo" "The Heart of Hyacinth" "A Japanese Nightingale"" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 16, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b5cc2f20-e840-0132-719e-58d385a7b928.

Onoto Watanna, The Wooing of Wistaria (1902). Image created by Project Gutenberg. Public domain.

autographed postcard, Fuji-ko (Florence Kent). Author's own collection.