The Alchemical Mr Gold

Jamie Barras

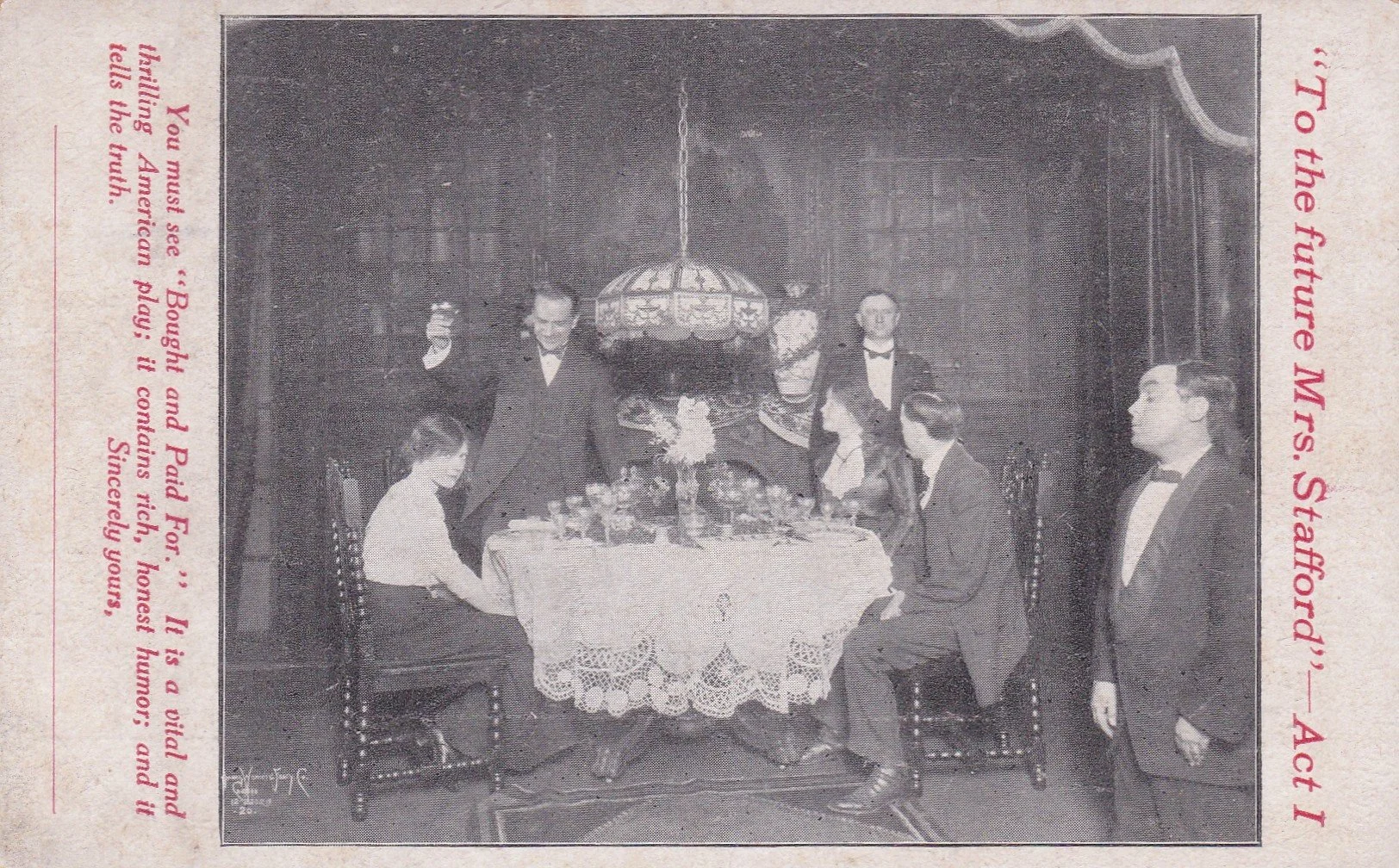

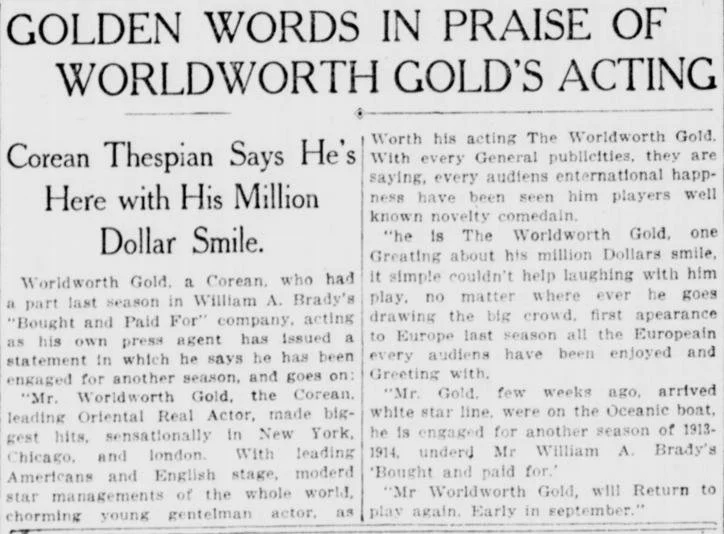

Worldworth Gold (1883–1858) was eccentric even by the standards of his adopted home, England. Born in what is now Korea at a time when the country was occupied by what was then the Empire of Japan, he went by many names: Kim In-Min (김인민, 金仁玟), Kim Sun Sure, Kim Giro, Kim Du Gle, Dandy Kim, Daniel Gold, Worldworth Gold, and Kimura Saketsu. ‘Gold’ was a direct English translation of his Korean surname ‘Kim’; the rest was his imagination. On his arrival in the US around 1907, he worked first as a ‘Japanese’ valet and then as an actor playing Japanese valets. He styled his off-stage personality and wardrobe on his idol and mentor, George M. Cohan (1878–1942), the Yankee Doodle Dandy himself. The New York theatre critics ridiculed his affectations and the long, rambling press releases with which he bombarded them. But they also published those press releases in full, which served Gold’s purpose. He was an eccentric, not a fool.

In 1913, Gold travelled to England in the London transfer of the hit Broadway play ‘Bought and Paid For’. Perpetually unlucky in love back in the US, within a month of his arrival in the UK, he married laundry worker Ida M Rider, only, at the end of the play’s run, to return to America without his new wife, intent on conquering Broadway a second time. Alas, Broadway gave him the cold shoulder. He retreated across the Atlantic once more to reunite with his bemused bride.

At the outbreak of the First World War, he volunteered for the British Army, seeing active service in the Rifle Brigade and earning the British citizenship he was awarded in 1919 the hard way. With the return of peace, he found work as a chandler, a valet, a film actor, and an artist’s model. He and Ida also had two children. The start of the Second World War saw him join a first-aid unit of the civilian Air Raid Precautions (ARP) service. The Daily Mirror, the largest-circulation English newspaper of the time, published a photo of him on its front page, dressed in his ARP uniform, with his First World War campaign medals pinned to his tunic vest, blue slippers on his feet, and a green silk parasol carried over one shoulder. Seeing the impact that aviation had had during the war, in 1947, he turned up at the London office of the United Press dressed in a red, green, and blue costume adorned with glass beads and regaled reporters with a plan to develop personal autogyros that everyone would wear on their backs. Still the dandy. Still the eccentric. Still making news.

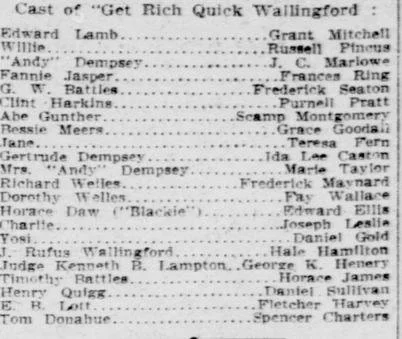

DU GLE KIM, a Corean Prince from Seoul, will enact the humble role of a valet to the hero, when George M. Cohan’s new comedy “Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford” has its premiere in New York. Kim has translated his name into Daniel Gold, and thus he will be known on the pay roll and in the cast. He is well educated, but was chef for a family on Riverside Drive when Mr. Cohan’s Japanese valet brought him to the first rehearsal. He did so well that the author-manager engaged him on the spot.[1]

The role of ‘Yosi’, Japanese valet to conman J. Rufus Wallingford, was original to the 1910 Broadway adaptation of the stories by George Randolph Chester. Added by the show’s creator, George M. Cohan, to serve as comic relief, Yosi was modelled on Cohan’s own Japanese valet, Yoshin Sakurai (1880–?), the man who introduced the future Worldworth Gold to Cohan. As Sakurai would perform the role himself the following year, it seems likely that Cohan had intended to debut him in the role until he saw Kim/Gold perform. We can even speculate that the character was called ‘Yosi’ because that was Cohan’s affectionate name for Sakurai.[2]

By the second decade of the Twentieth Century, Japanese domestic servants were in high demand in America due to the perception of white employers that they were naturally “polite, careful, and intelligent” and “clean, clever, and ambitious.”[3] Although this was racial stereotyping, it was a bias that Japanese immigrants were keen to exploit, as they were barred from many other forms of occupation by racist hiring policies and land ownership laws. Those same restrictions, particularly prevalent on the West Coast, where most Japanese immigrants settled, also prompted a steady stream of young Japanese men and women to try their luck on the Eastern seaboard and Great Lakes Region

This was the society in which Gold moved, exploiting that same bias as he was subjected to those same forces, even though he was Korean by birth. In this context, it must be remembered that, at the time, the country we now know as Korea was occupied by what was then the Empire of Japan. Japan had gained control of the country following the former’s victory in the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. In 1910, the year that Gold debuted in ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford’, Japan formally annexed Korea and abolished its system of government, marking the beginning of attempts to assimilate it and its population into the Japanese Empire. Korea would not regain its freedom until the surrender of Japan at the end of the Second World War.[4]

We have two travel records for Worldworth Gold. In both, his nationality is listed as ‘Japanese’, reflecting the fact that his travel documents would have been issued by the Japanese colonial government; he may also have travelled to the US via Japan. In one of the records, the name ‘Worldworth Gold’ has had the name ‘Saketsu Komura’ added above it, which may have been the name that he used when he lived in Japan or among Japanese people.[5] Given the complicated situation in which both Korea and its nationals found themselves in this period, it is also not surprising to learn that Gold would sometimes refer to himself as Korean and sometimes as Japanese. From all this, it can be argued that he started ‘playing Japanese’ long before he took to the stage.

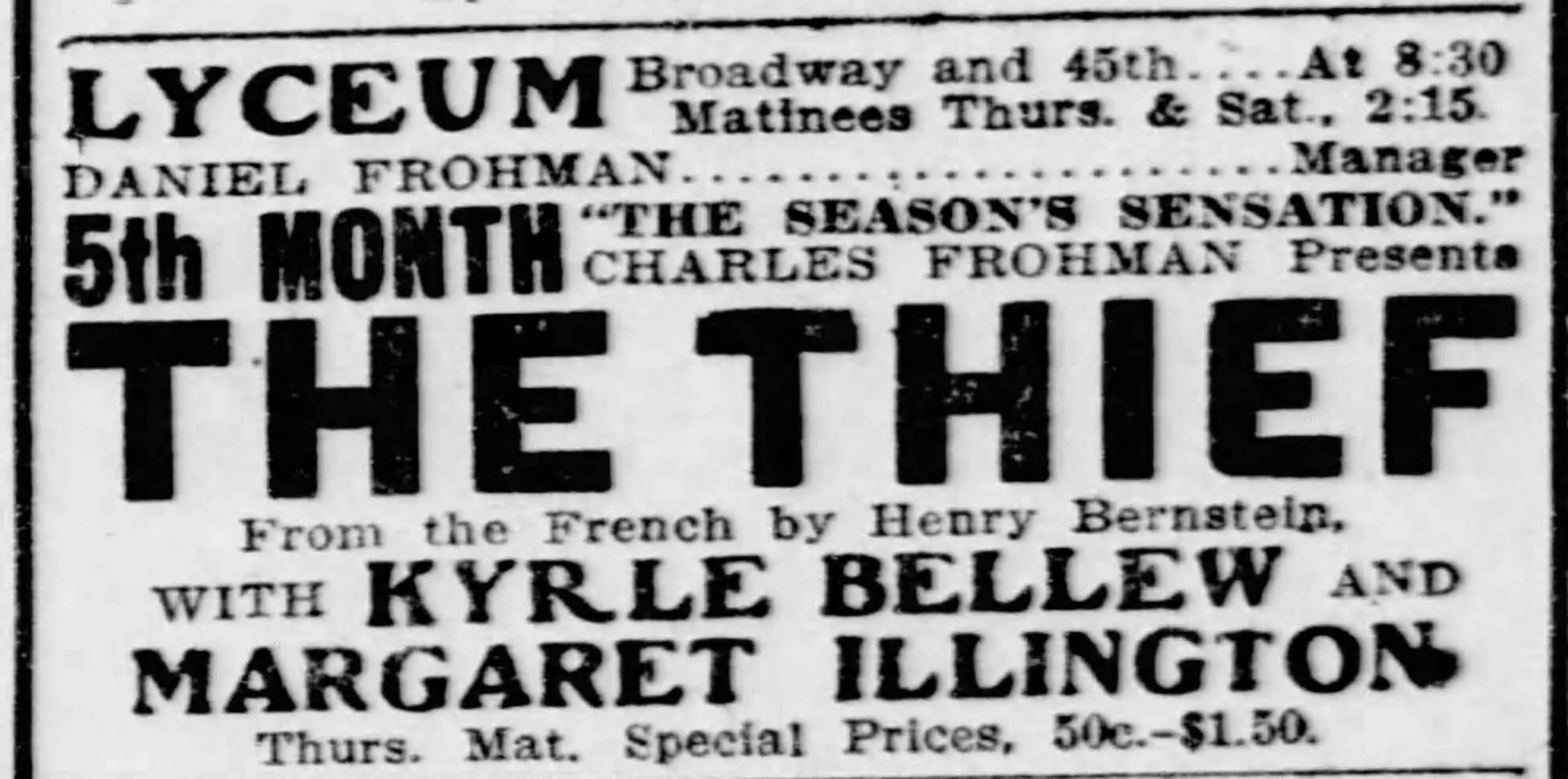

[…]he left his own country to u.s.a., san francisco, cal. Mr. gold remain’s year so in the westside, then come to new york city years vacational, 1908. He went to personal valet to english actor, three months acting at the dressing room’s rehearsal. Learned from mr. kyrl bellew, was with cha’s frohman’s the thief, 1909, take ajap part, with the air to the hoorha.[6]

Gold’s own press releases, for all their unique use of the English language—which, it should be remembered, served Gold’s purpose very well—prove to be a surprisingly reliable source of information on his life in America (although the same cannot be said in regard to his real name—as we will discuss below). We can point to contemporary newspaper reports that place him in New York in 1908 in the employ of English-born actor Kyrle Bellew (1850–1911), using the name ‘Dandy Kim’, and, using the same name, performing the part of ‘Hush’, a Japanese valet, in a 1909 production of the play ‘The Heir of the Hoorah’ (the ‘air of the hoorha’ in the above quote—the play had a western setting and the ‘Hoorah’ was a gold mine).[7]

(As an aside, the role of Hush in ‘Heir to the Hoorah’ was originated in 1905 by Japanese actor T. Tamomoto. Tamamoto had been in the US since 1900, having arrived in the country with the famous Kawakami Troupe led by Otojirō and Sadayakko Kawakami. This is a noteworthy, very early example of an East Asian actor appearing in an American production.[8])

According to Bellew, Gold/Kim chose the name ‘Dandy’ for himself.

[He] wore an olive green suit, purple tie, emerald plush waistcoat, and his chromatic glorias were completed by a pink silk scarf about his neck which he wore in lieu of an overcoat. Although he gave Boston and its polite public a fearful shock, he attracted so much attention, he decided that valeting was far beneath him and that he had possibilities as a professional beauty.[9]

It is no wonder that Gold would find so much to admire about George M. Cohan when he met him at his audition for ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford’.

Given the veracity of the information Gold provided in his press releases about his American adventures, we have every reason to take his statements about his parentage at face value, too. He claimed to be the orphaned son of a doctor of medicine named ‘Kim Insir’ (Kim In-Seo, 김인서, 金仁瑞?) and descended from Korean royalty—although this is not to say that the latter connection was not very distant.[10]

Following the same logic, it seems reasonable to believe what Gold had to say about his attempts to find a bride after he arrived in America.

Went to Mexico try to marry original girl, but he was too late nice girls all gone[…]Then went to san francisco, cal. Engaged to marry beauty and Rich chanese girl[…]name Miss E. Woo Sen. She told Mr. Gold you have to wait four years more. Daniel he doesn’t understand whats the reason. Because Mr. Gold, answer to her he do no, wait or not. Another Japanese beauty Girl Miss Yucoma she Roun after to ‘Daniel Gold. said shes beauty alrigth but she have no money.[11]

We can see in these misadventures both a young man’s eagerness to experience all the joys that marriage can bring and an attempt by someone set adrift by world events to find an anchor (and a provider?). The Mexican episode is particularly interesting, as six months before Gold sent out the press release quoted above, reports had appeared in US newspapers that Yoshin Sakurai, George M. Cohan’s former valet and the man with whom Gold shared the role ‘Yosi’ in ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford’, was having romance troubles of his own in connection with Mexico. He had answered an advertisement in a Japanese-language newspaper from Yumi Oh, a young Japanese woman living in Mereda, Mexico, who was seeking a Japanese husband. Sakurai answered the ad, and he and Yumi-san contracted to marry, only for their relationship to run afoul of US immigration laws.[12] Had Gold answered a similar—or even the same—ad?

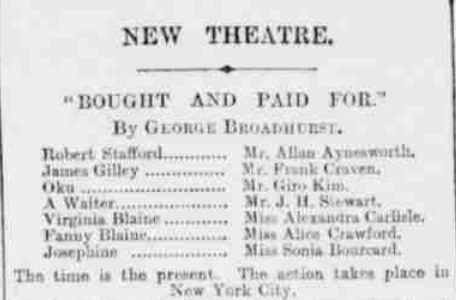

In the cast of ‘Bought and Paid For” this week at the Teck Theater is a Corean actor who for sartorial perfection and general deportment has the Broadway dandy backed off the boards. Also, Daniel Gold, the Oriental thespian, is some actor.[13]

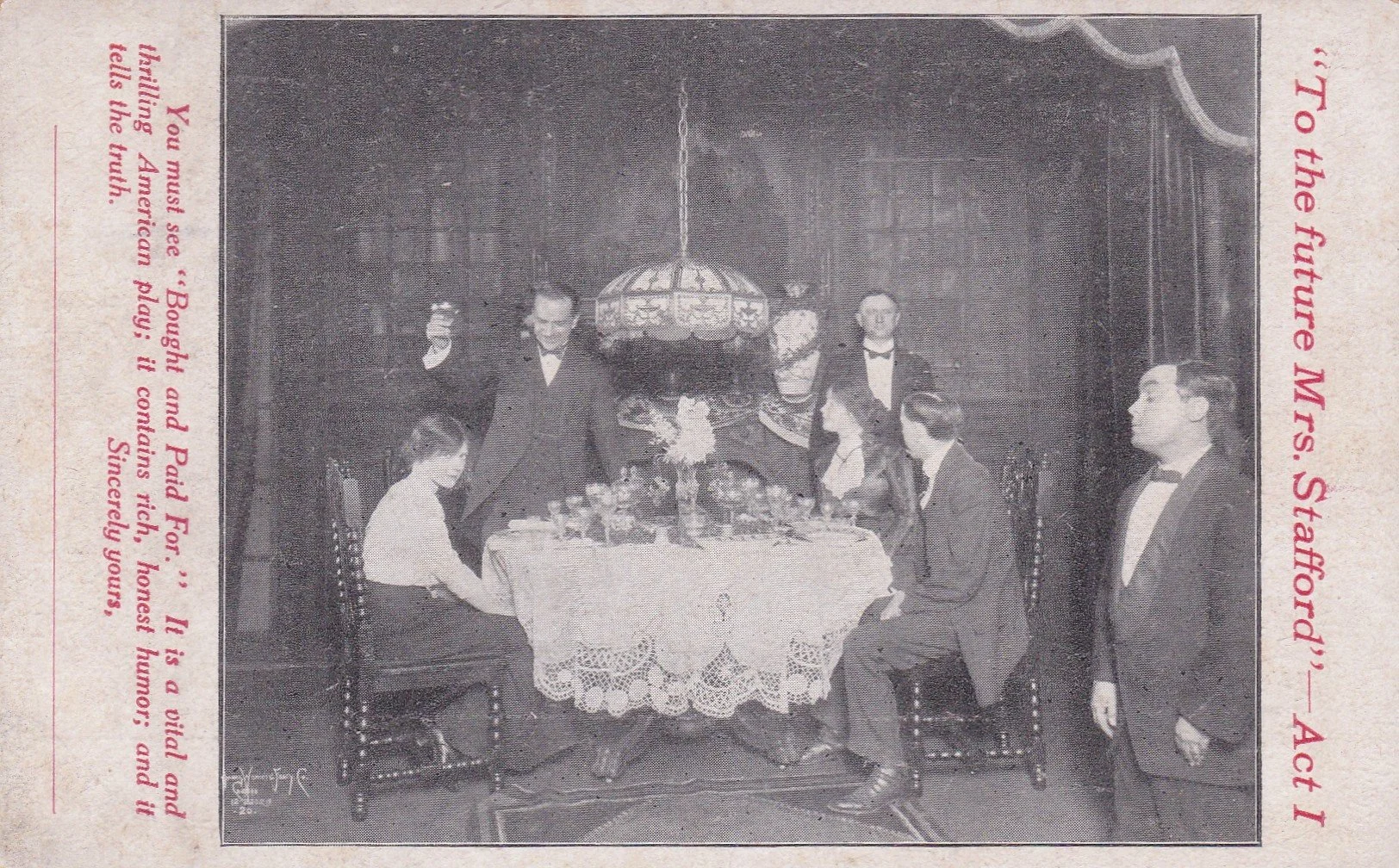

Gold left the production of ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford’ in March 1912, after nearly 18 months. Though his part was small—two lines—his earnings playing the role of a Japanese valet far outstripped those of an actual Japanese valet. His next role would be ‘Oku’, another Japanese valet, in what would be another hit Broadway show, albeit in one of its touring productions. This was ‘Bought and Paid For’, the show that would eventually bring him to England.[14]

The role of ‘Oku’ in the Broadway production was originated by Allan Atwell, one of a number of Caucasian actors of the period who specialised in ‘yellowface’ roles. This was Atwell’s sixth such role, and, typically for the period, he was said to be so good at playing Japanese characters that audiences could not tell he was white. Similar sentiments were expressed in regard to the performance of Adrian H. Rosley, who took the role in another of the touring productions. Rosley was said to have ‘lived among the Jap[anese]’ for several months and speak Japanese fairly well. Both actors had the same anecdote told about them in connection with their performance as Oku, one that centred on someone betting that they had to be Japanese because they were so good, only to lose the bet when the actor appeared at the stage door without their makeup. Like Gold, Atwell would eventually find his way to England, albeit only for a brief period; while here, he played two roles in the same play, one Chinese and the other Japanese.[15]

That Caucasian actors could make a career from performing ‘yellowface’ roles is a measure of the popularity of plays with East Asian themes or elements in this period. Although arguably the ‘craze’ for Japanese-themed entertainment had peaked five years earlier with Puccini’s operatic treatment of Madama Butterfly following David Belasco’s non-musical treatment of the story on to the New York stage, where it vied for attention with Belasco’s follow-up to his ‘Madame Butterfly’, another Japanese-themed work, ‘Darling of the Gods’, and rival producers Klaw and Erlanger’s adaptation of the novel, ‘The Japanese Nightingale’. However, alongside the soon-to-be ubiquitous presence of Japanese valets as supporting characters (replacing English butlers and complementing French maids), the 1910s also saw the debut of more sophisticated Japanese-themed works like ‘The Typhoon’—both Atwell and Gold would be connected in the press with upcoming productions of the latter.[16]

Although some of these productions, ‘The Typhoon’ being a good example, featured broadly positive portrayals of East Asian characters, this was tempered by the fact that the main roles invariably went to white actors in yellowface. East Asian actors, if cast at all, were relegated to support roles; as was the case with African American performers, too often these support roles were caricatures, there only to provide either comic relief or over-the-top villainy. The question of whether any representation was better than none remains hotly debated.[17] For Gold and Sakurai, it was probably simply preferable to be viewed as actors rather than as servants.

Mr. Brady is playing fair with the public and giving the Chicago patrons the same cast which played 278 performances in New York. The cast includes[…]Worldworth Gold, a Korean actor.[18]

The most remarkable aspect of Gold’s casting in ‘Bought and Paid For’ was not the role, which was, in almost all respects, a repeat of the Yosi role from ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford’, but how quickly Gold got through stage names during the first few months of its run. His casting was announced under the ‘Daniel Gold’ stage name he had created for ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford’; however, by the time he began to perform, he was being billed as ‘Worldworth Gold’. The explanation for the name would only come once the play transferred to London in March 1913, by which time, Gold’s billing had changed again.

He is billed at the New Theatre as Giro Kim, and his real name in Korean is Kim Sun Sure, but he does not like any of these Oriental names, and has adopted the cognomen of Worldworth Gold, and wants to be known by that name only off the stage. ““Worldworth Gold” good name, don’t you think?” He exclaimed. “It respectable name and sounds good. I don’t use it on stage, because public might think me not genuine Jap.”[19]

This reference to his ‘real name’ being Kim Sun Sure is a rare example of something that Gold said of himself that I think we cannot take at face value. When he was cast in ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford’, the papers reported his name as ‘Du Gle Kim’; even allowing for errors in transcription, it is hard to map this to ‘Sun Sure Kim’. More than this, within a month of his arrival in England, he would sign a different name to an official document, his marriage registration.[20] That name was Kim In-Min (김인민, 金仁玟), and I think that this was probably his real name, both because this was an official document and because it was the name he gave in connection with his marriage, an event he had invested a lot of time in bringing about. A fake name would not have matched the seriousness of the enterprise. It was in this same document that he gave his father’s name as ‘Kim Insir’, and while it must be acknowledged that it is rare for the same character to appear in the given names of two generations of a family—this is something generally reserved for siblings in Korean tradition, where it is known as a ‘generation character’ (항렬자, hangnyeolja)—it is not unknown, and was more common in the past.[21]

Gold met his new bride, Ida Mary Rider, on his second day in London, in a Japanese shop in Piccadilly.[22] True to form, he sent the New York critics a press release telling them of his good fortune.

She just genuine nice English girl—not like other girls I know in America. I don’t like flighty girls that go out with other chaps. Her name is Ida Rider, and she be 21 come 14 next June. I see her every day, but not easy, because she is in business[…][23]

Ida Mary Rider (1892–1978) was born in Walworth, London, in July 1892, the daughter of Ernest William Rider, a druggist, and Eliza Rider née Vickery. Her father died when she was just 3, leaving her mother, Eliza, to raise five children alone. By 1901, Ida, aged just 7, and her older brother, Charles, were confined to a workhouse in Hanwell, while their mother was working as a cleaner in a workhouse in Camberwell. When Ida met Gold in 1913, she was working at a laundry and living in lodgings.[24]

It is easy to imagine the effect that Gold, richly dressed, worldly, intense in personality, and very ready for love, had on a 21-year-old orphan raised in grinding poverty. On Gold’s part, Ida was probably the first woman he had talked to since arriving in England, or more particularly, perhaps, the first woman who had talked to him. That both Gold and Ida’s fathers were dead was something the pair had in common. More than this, as Gold came from a country where the Chinese system of medicine prevailed, which relied much more on finding the right mix of natural remedies to cure a complaint than prescribing mass-market medicines, he would have seen in Ida’s description of her father’s job as a druggist much in common with his memories of his own father’s approach to medicine.

The reason for the rushed wedding, beyond Gold’s eagerness, was the imminent end of the West End run of ‘Bought and Paid For’ and the return of its American cast, Gold included, to New York. Before he left, Gold provided his new bride with living expenses for a year and a new trousseau (he also emptied the London tailors of clothes for himself). He expected that, once he had reestablished himself as a Broadway star, Ida would join him in America. However, instead, while he was still hunting for work, he received a letter from Ida to say that she had decided to remain in England.[25]

Whether Ida saw this as the end of their very brief relationship or intended it as a spur to Gold to abandon his dreams of Broadway stardom is not clear. If it were not for the fact that the couple did reunite and spend the rest of their lives with each other, one might suspect that Ida had only been after her living expenses and a new trousseau from the very start. It seems likely that she thought better of leaving behind the support system she had in London among her family and friends to cross an ocean to live with an out-of-work actor, and was ready for whatever the outcome of that decision.

WANTED Known, Japanese (32), Useful Valet or Serious Light Comedian, Disengaged. Will any author write special part and introduce him to any leading new production? Good references from United States and England. Write or wire, GIRO KIM, 39, Gloucester Road, Peckham.[26]

Worldworth Gold returned to England sometime in late 1913 or early 1914 and reunited with Ida. In the 1911 and 1921 England Censuses, only a handful of people listed ‘Korea’ as their place of birth. The vast majority of these were people of British parentage (e.g., the child of missionaries or government officials). Of those of Korean heritage, in 1911, there was only ‘Hi Chin’, a 21-year-old ‘Chinese tailor’ living in a rooming house in Cardiff, Wales. [27]

By 1921, the numbers were higher, but most of these were sailors either on ships in port or on shore without a berth. A notable exception was Korean American journalist Earl Whang Ki-Whan (1886–1923), who was in charge of the London mission of the Korean Independence movement. A survivor of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and World War One veteran, back in 1911, Whang had run afoul of US authorities for crossing state lines with his white girlfriend—something that earned him the title “white slaver” in the hysterical and racist US press. During his time in charge of the London Mission, Whang would also serve as the Korean delegate to the 1921 Imperial Conference in London, held to determine Britain’s response to the rise of the Empire of Japan and the USA. At the time, he issued a statement painting Japan’s occupation of Korea as merely the first step in its plan for domination in Asia. He was right, but his warnings fell on deaf ears. He died of a heart attack in New York in 1923.[28]

Of course, how many of the hundreds of people in the 1911 and 1921 England Censuses who listed ‘Japan’ as their place of birth were of Korean origin, it is impossible to know. Regardless, to all intents and purposes, when Gold settled in England in 1913/14, his English family became his community. This would be cemented when he took British citizenship in 1919, after seeing active service in the First World War.[29]

We can only speculate about what motivated Gold to join the British Army in the early months of the First World War—he was almost certainly the only person of Korean heritage to see service in the British Army in the conflict. Ida would have already been pregnant with the couple’s first child, Gladys Ida Gold (1915–1973), who would be born in the spring of 1915, when Gold, who had been running a chandler’s shop, volunteered.[30] It is possible that Gold’s decision was a mixture of patriotism for his new home and economic necessity.

Gold became a private in the 11th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own), which deployed to France in 1915. As Gold was later awarded both the British War Medal and the Victory Medal, the latter of which was only for soldiers who served in a theatre of war, he must have spent at least part of his service in France, perhaps even on the front line; however, at some point, he was transferred to the brigade depot back in England. There is no record of service beyond 1915, and he and Ida would have a second child, George Morgan Gold (1917–1987), in the summer of 1917, suggesting that Gold was back in London for at least some of 1916. Based on this, it seems that he was discharged from the army sometime in 1916. As he would subsequently be awarded medals and a pension for his service, we can be sure that this was not a dishonourable discharge. A wound or some other kind of infirmity seems the more likely cause of his discharge. It is also possible that the British Army simply didn’t know what to do with this most individual of men.[31]

Green silk parasol with a red tassel and bright blue shoes complete the uniform of this London A.R.P. volunteer. He’s Mr. Wordworth Gold, native of Korea, now storekeeper for a Holborn first-aid unit. On his chest he proudly carries two ribbons of medals he won in the last war as a private in the London Regiment. “I’ve been a naturalised British subject for twenty-eight years,” he told the “Daily Mirror”. “It wouldn’t be right to have enjoyed all the privileges that brings without sharing some of the responsibilities.”[32]

The 1921 England Census found the Golds—Worldworth, Ida, Gladys, and George—living in the Millbank Estate in Westminster. This London County Council (LCC) housing estate was high-quality social housing; the Golds would have had school teachers and police officers for neighbours. For his own part, Gold had returned to his old job of being a gentleman’s valet. His employer was physician Dr Arthur Bevan (1876–1951) of Gloucester Place, Marylebone; a suitably upmarket address for a man who could afford to keep a ‘Japanese’ valet. There was one other person staying with the Golds the night of the census; this was Ona Jung, a 28-year-old dressmaker described as a visitor, single, born in Korea, and, like Gold, naturalised British.[33] Was Ms Jung a relative of Gold’s, or someone he had come to know through contact with the nascent Korean community in London? How was it that a single woman became naturalised British—was she adopted as a child by a British family? Alas, although there is surely a story to tell here, I have to date been unable to find out anything more about Ms Jung.

Although Gold would continue to describe himself as an actor—adding film acting to his credits—he either stopped bombarding the New York critics with press releases or they stopped publishing them, and so, alas, the details of this time in his life can only be gleaned from public records. In 1933, the Gold family moved from the Millbank Estate to the Drury Lane Estate, another LCC social housing project, this one right in the heart of the West End. This would be their home for the next 20+ years. Daughter Gladys was by this time a commercial designer; in 1935, she married car mechanic John Stanghon, and the two set up home together in Lambeth. The Golds’ son George became an engineer. He never married. He also never left home, continuing to live with Worldworth and Ida into middle age. This would be unusual in a British family, but it was in keeping with Korean tradition.[34]

By the Spring of 1939, Worldworth had added artists’ model to his CV. He had also, as we have seen, found his way back onto the front pages of the newspapers thanks to his ARP service and unique additions to the uniform. The Drury Lane area was struck several times by bombs and at least one V-1 flying bomb during the Second World War—Gold would have been kept busy at his first-aid post—however, all the Golds came through the war alive. His ARP service had a profound effect on Gold, however, and following the end of the war, his thoughts turned, somewhat improbably, to the peaceful use of rockets and other flying machines.

LONDON, Feb. 5 (U.P.)—Worldworth Gold, a 65-year-old Korean, is an ardent one-worlder who wants to achieve that objective by the use of rockets and autogyros. The V-2 rocket, he thinks, could be adapted by a complicated system of auxiliary motors to carry passengers safely. And everyone would have his personally fitted autogyro. “Then you would have to just reach back here and turn a switch,” He said, indicating where a switch probably would be. “Then traffic doesn’t worry you any more.” Gold rattled the glass beads which adorn his self-designed costume of red, blue, and green and revealed his basic aim. “I want to push back the walls and the ceiling and the floor,” he said, stamping on the floor of the United Press Office. “Yes, with an autogyro you could push back the floor, too.”[35]

Still the dandy. Still the eccentric. Still making news. Worldworth Gold died in London in 1958, aged 75. He was survived by Ida, his wife of 45 years, and his two children. Gladys and George. Korean by birth, Japanese by force, and British by naturalisation, he was a singular individual. It has been a pleasure researching his story.

Jamie Barras, December 2025.

Back to Staged Identities

Notes

[1] ‘The Corean Prince Becomes An Actor’, Toronto Star, 1 October 1910.

[2] Elizabeth T. Craft, 'The Man Who Owned Broadway', Yankee Doodle Dandy: George M. Cohan and the Broadway Stage (New York, 2024; online edn, Oxford Academic, 18 July 2024), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197550403.003.0004, accessed 24 Dec. 2025. Sakurai’s year of birth is taken from his draft registration: "United States, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XT7N-C6F:Mon Apr 28 19:39:46 UTC 2025), Entry for Yoshin Sakurai, 1942.

[3] Takako Day, Japanese Garden Designers, Domestic Workers, and their “Japanophile” Employers, https://discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2022/6/5/Illinois-Japanese-1/, accessed 24 December 2025.

[4] S. Lone, “The Japanese Annexation of Korea 1910: The Failure of East Asian Co-Prosperity”, Modern Asian Studies, 1991, 25(1), 143–173. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00015870. Kim Ji-Hyung. "The Japanese Annexation of Korea as Viewed from the British and American Press: focus on The Times and The New York Times", International Journal of Korean History, 2011, 16, no.2, 87–123.

[5] Entries for Worldworth Gold in the passenger lists for the RMS Oceanic, leaving Southampton, 28 May 1913, and arriving New York, 6 June 1913; UK and Ireland, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960, New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 22 December 2025.

[6] ‘‘World-Worth Gold’, Jap Valet, Tells the Story of His Life’, Chicago Tribune, 19 January 1913.

[7] Kyrle Bellew: https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bellew-harold-kyrle-money-5198, accessed 24 December 2025. ‘Dandy Kim’, Bellow’s valet: ‘Kyrle Bellew—and Man’, Washington Herald, 20 January 1909. ‘Dandy Kim, a little Jap’, playing Hush in Elmira, New York, 1909: ‘Audience Enjoys “Heir to the Hoorah”’, Elmira Star-Gazette, 13 October 1909.

[8] ‘This Week At The Theaters’, Kansas City Star, 19 January 1905.

[9] ‘‘World-Worth Gold’, Jap Valet, Tells the Story of His Life’, Chicago Tribune, 19 January 1913.

[10] See Note 6 above for orphan story and father a doctor. ‘Kim Insir (deceased)’, ‘doctor of medicine’, is how he describes his father on his 1913 marriage registration: entry for Worldworth Gold, 6 April 1913, Westminster, London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1935, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 22 December 2025. Kim family name and royalty: https://www.britannica.com/story/why-are-so-many-koreans-named-kim, accessed 24 December 2025.

[11] ‘Japanese Idea of Press Agent Matter’, The Spokesman Review (Spokane, WA), 14 April 1912.

[12] ‘Calling of Great Desire Felt by Japanese Actor’, Dayton Herald (Dayton, OH), 21 October 1911.

[13] ‘Corean Actor has Part in Play’, Buffalo Enquirer, 21 November 1912.

[14] See Note 12 above for Gold’s departure from ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford’.

[15] Allan Atwell: ‘An American Jap’, Philadelphia Enquirer, 9 February 1913. Adrian Rosley: ‘Amusements: At The Lyceum’, Duluth News Tribune, 1 January 1913. Atwell version of bet story: ‘Bought and Paid For’, Great Falls Leader, 30 September 1912; Rosley version: ‘Not a Sure-Enough Jap’, Minneapolis Journal, 20 November 1912. Atwell in England: ‘The Man Who Came Back’, Evening News (London), 9 April 1920.

[16] I discuss the rage for Japanese-themed entertainment in the first decade of the twentieth century here: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-bakeneko, accessed 25 December 2025. Gold and Typhoon: ‘His Modesty is Killing’, The Republican (Washington, DC), 2 May 1912.

[17] Josephine Lee, “Stage Orientalism and Asian American Performance from the Nineteenth into the Twentieth Century.” Chapter. In The Cambridge History of Asian American Literature, edited by Rajini Srikanth and Min Hyoung Song, 55–70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

[18] ‘Bought and Paid For’, Herald Press (Saint Joseph, MI), 17 December 1912.

[19] ‘The Korean Dandy, Bradford Telegraph and Argus, 19 March 1913.

[20] See Note 10 above, second reference.

[21] https://flexiclasses.com/korean/names/, accessed 27 December 2025.

[22] ‘Japanese Valet in Famous Play Gets Pretty Wife’, Calgary Herald, 12 April 1913.

[23] ‘Romance of a Korean’, Flint Journal, 19 April 1913.

[24] Census returns for Ernest William Rider, 1881 England Census, Walworth district, William Rider, 1891 England Census, Walworth district, Ida Rider, Hanwell district, and Eliza Rider, Camberwell district, 1901 England Census, and Ida Mary Rider, Camberwell district, 1911 England Census; ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 22 December 2025. Year of death of Ernest William Rider: search of births, marriages, and deaths, St Saviour, Southwark, district; year of death of Ida Mary Gold, search of births, marriages, and deaths: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 26 December 2025.

[25] ‘New York Letter’, Cleveland Press, 13 August 1913.

[26] ‘Artistes’ Wants’, Era, 9 September 1914.

[27] Search of 1911 England Census by place of birth (‘Korea’ (including ‘Joseon’), ‘Japan’), familysearch.org, accessed 26 December 2025; search of 1921 England Censuses by place of birth (‘Korea’), ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 27 December 2025.

[28] Earl Ki-Whan Whang, Kensington District, 1921 England Census, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 27 December 2025. ‘Five Trainloads of San Francisco Refugees Arrive’, Los Angeles Herald, 23 April 1906; ‘Trace White Slaver Through This City’, Morning Press (Santa Barbara, CA), 14 May 1911; ‘Our London Letter’, Eastern Daily Press (Norwich), 18 October 1921; E.K. Whang, ‘Korean Seizure Seen Start of Jap Dominance’, Times Herald (Washington, DC), 2 December 1921; ‘Freedom for Koreans’, Montreal Star, 4 September 1945. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2023/04/10/national/socialAffairs/Korea-Whang-Kihwan-independence-activist/20230410180034567.html, accessed 27 December 2025. Whang was the inspiration for the protagonist of the 2018 Korean TV drama ‘Mr Sunshine’ (미스터 션샤인).

[29] Record Transcription_ Britain, Naturalisations 1844-1990 _ findmypast.co.uk, Sun Sure Kim; Record Transcription_ Britain, First World War Campaign Medals _ findmypast.co.uk, Worldworth Gold, accessed 22 December 2025.

[30] Entry for Worldworth Kim, Miniver Street, Southwark, Post Office London Directory, 1914. [Part 2: Street Directory], https://leicester.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16445coll4/id/143084, accessed 26 December 2025; birth record for Gladys I Gold, mother’s maiden name Rider, search of births, marriages, and deaths: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 26 December 2025.

[31] For Military record, see Note 29 above, second reference; birth record for George M. Gold, mother’s maiden name Rider, search of births, marriages, and deaths: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 26 December 2025. Death record for George Morgan Gold, search of births, marriages, and deaths: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 26 December 2025.

[32] ‘Green silk parasol…’ Daily Mirror, 25 September 1939.

[33] Entry for Worldworth Gold, Ida Mary Gold, etc., Millbank, Westminster, 1921 England Census; entry for Dr Arthur Bevan, Paddington district, 1911 England Census; ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 22 December 2025; ‘A Petersfield Bridegroom’, Portsmouth Evening News, 14 April 1926. Millbank Estate: https://alondoninheritance.com/london-buildings/millbank-estate-millbank-penitentiary/, accessed 26 December 2025.

[34] Electoral Register search for Worldworth Gold, Ida M. Gold, and George M. Gold, 1918–1958, Westminster, London, Electoral Registers, 1902–1970; 1939 England Register entries for John and Gladys Stanghon, Lambeth district, Ida M. Gold and George M. Gold, Westminster, and Wordsworth [sic] Gold, Westminster district; ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. (Operations), accessed 27 December 2025. Marriage search for Gladys I. Gold and George M. Gold, births, marriages, and deaths, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 27 December 2025. Drury Lane Estate (Stirling Buildings): https://stilwellhistory.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/early_lcc_housing_part_3_21-clare_mkt_strand_improvement.pdf.

[35] ‘Korean Would Use Autogyro for World Travel’ Daily Herald (Provo, UT), 5 February 1947.

A scene from 'Bought and Paid For', 1912, postcard. Author's own collection.

Dandy Kim In-Min AKA Worldworth Gold, as he preferred to be seen. New York Tribune, 17 April 1912. Image created by Library of Congress. Public domain.

George M. Cohan, Gold's idol and mentor. National Portrait Gallery. Public domain.

Advertisement for 'The Thief', starring English-born actor Kyrle Bellew, who, for a time, employed Gold, then calling himself 'Dandy Kim', as a valet. New York Tribune, 5 January 1908. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain. It was while working for Bellew that Gold caught the acting bug.

Cast of 'Get-Rick-Quick Wallingford', featuring Gold, using the stage name Daniel Gold, in the role of 'Yosi', a Japanese valet. New York Tribune, 20 September 1910. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Cast list, 'Bought and Paid For', London, featuring Gold, using the stage name Giro Kim, in the role of 'Oku', a Japanese valet. Morning Post, 13 March 1912. Image created by British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

One of Gold's memorable press releases. New York Tribune, 30 June 1913. Image created by the Library of Congress. Public domain. The US press ridiculed him for his pretensions and unique way with English, but published the releases in full. Gold was no fool.