The Violet Ray

Jamie Barras

The great feature of the performance is, of course, the five dances by Loïe Fuller. There can be no doubt that the originator of the serpentine dance still holds her supremacy, and now that many of her creations are protected, Mr. Stevens, her 'cute manager, keeping a watchful eye on everybody who trespasses on her rights, she will continue to shine as the great and only star of her kind.[1]

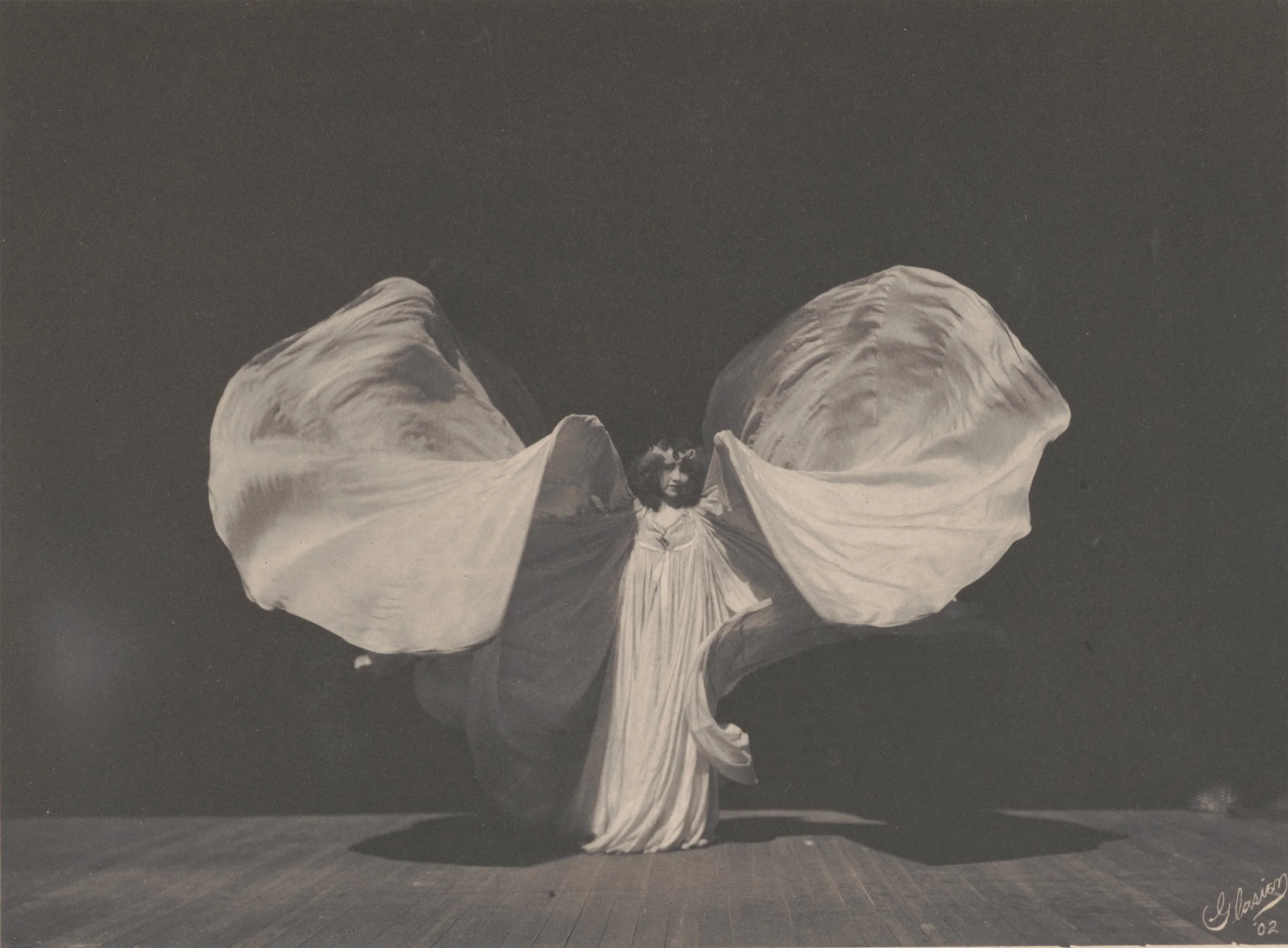

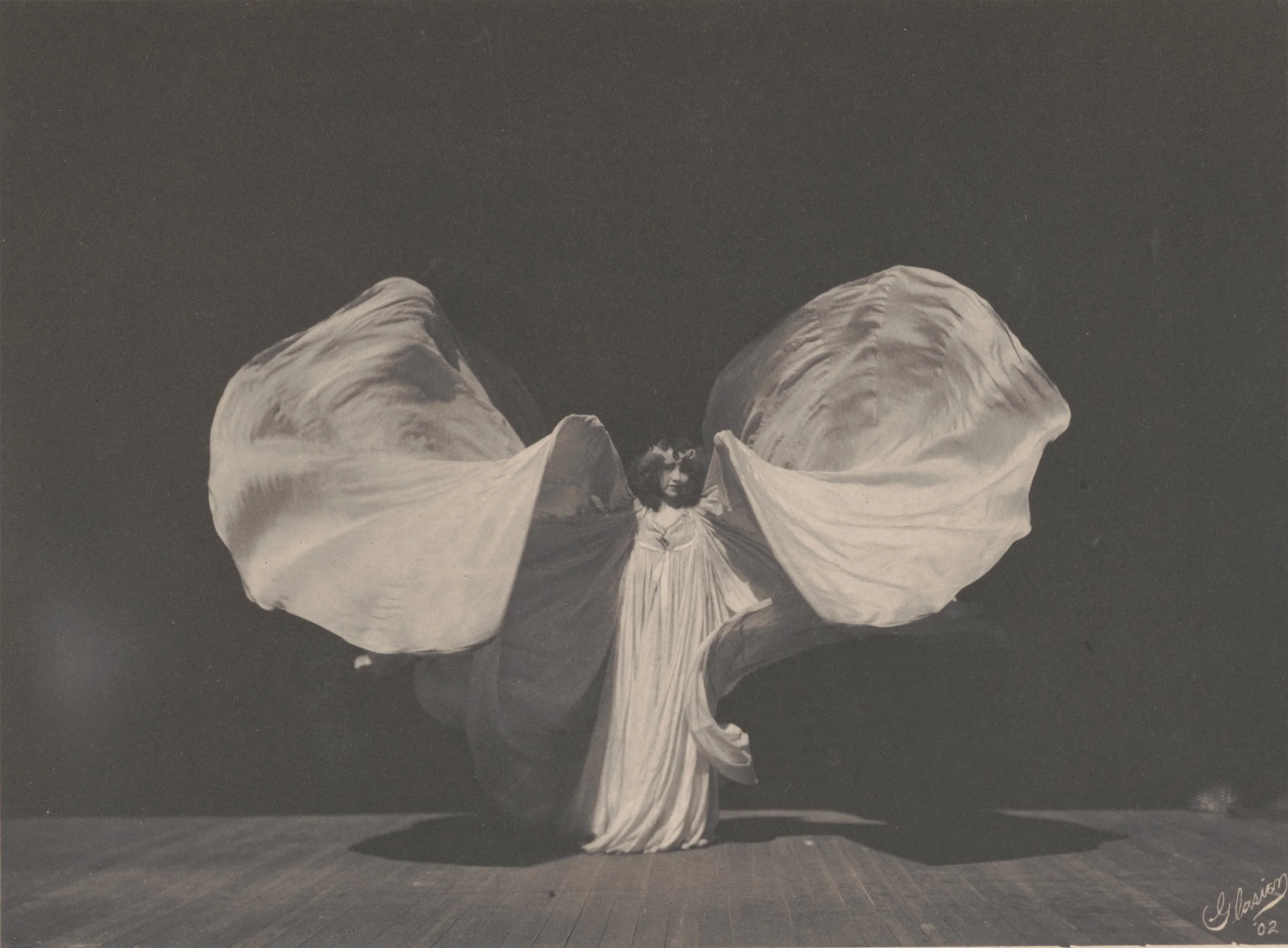

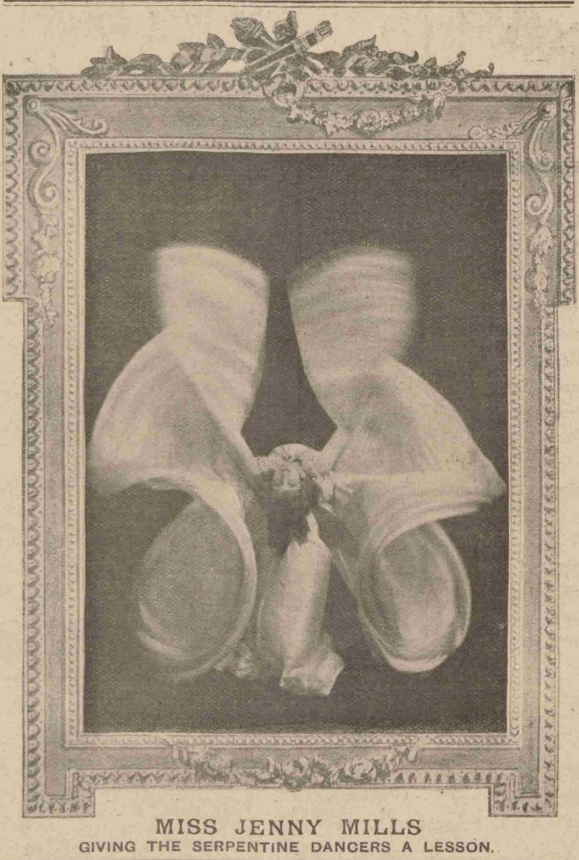

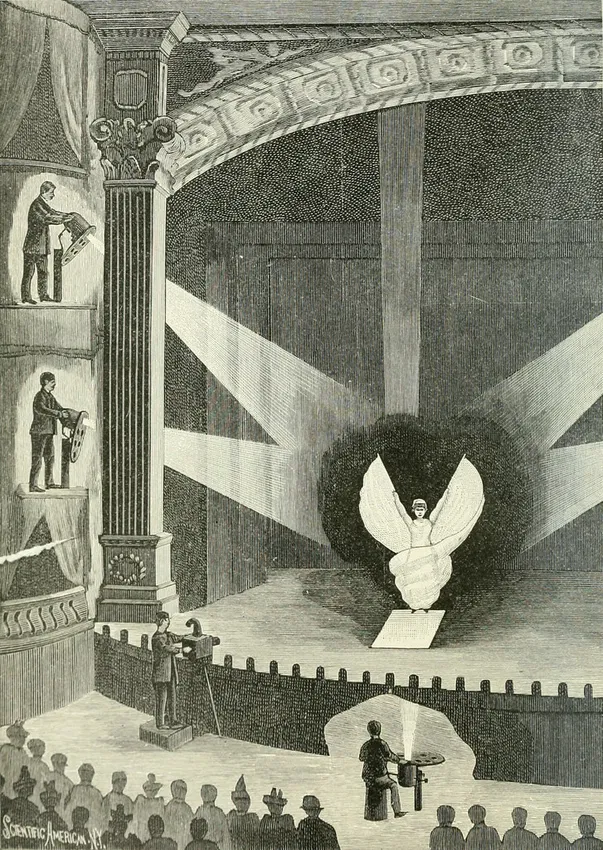

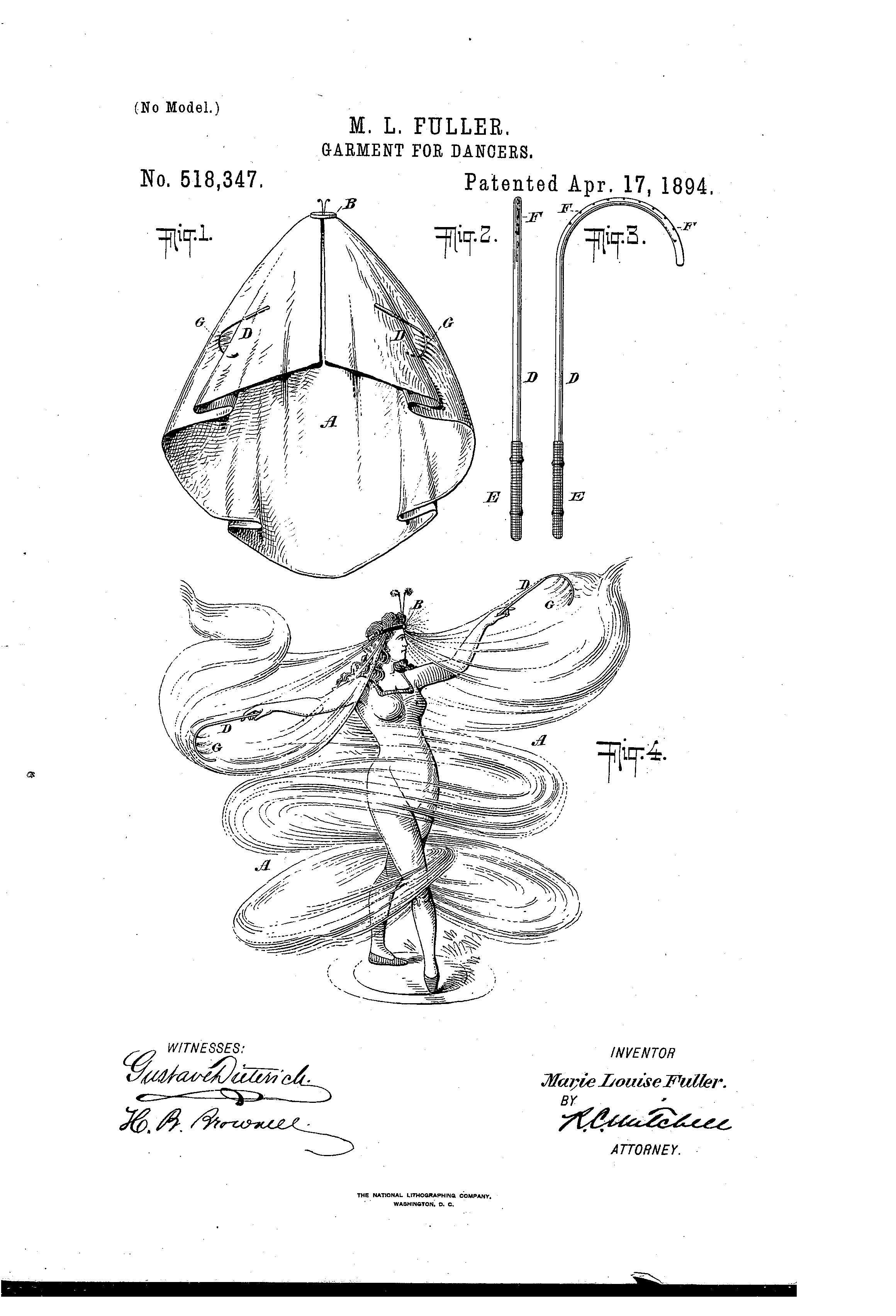

Loïe Fuller (1862–1928) was an original. Born Marie Louise Fuller in Illinois in 1862, she toured with Buffalo Bill, went broke putting on her own show in London, perfected a new type of dance performance in New York, but then lost money in a failed attempt to copyright it. She lost even more money on a disastrous tour of Germany before, finally, finding fame and fortune at the Folies Bergère in Paris. Her greatest creation was the serpentine dance, a skirt dance made fantastical by multi-hued beams of light projected onto the swirling, billowing train of Fuller’s costume from many directions, including from under a glass floor. Fuller herself developed many of these effects and patented several aspects of her costume design and stage effects.[2]

Yes, Fuller was an original; she was not, however, a one-off. Her reliance on lighting effects made her act easy to replicate by anyone who was in on the secret, which included all her lighting technicians, who, in the act’s fully developed form, numbered as many as 30 per performance. This made the greatest source of Loïe Fuller imitators her own inner circle. Her sister-in-law, Ida Fuller, was one of the more successful copycats, touring an act created by her husband, Loïe Fuller’s brother, Frank Fuller.[3]

And then there were the many acts created by Fuller’s one-time lead technician, Percy Boggis.

Miss Fuller is constantly introducing new dances, and with the aid of her own efficient electrician, Mr. Percy Boggis, also fresh and marvellous light effects.[4]

Percy Harold Boggis (1873–1950)—Boggie to his friends—was born in Sydney, Australia, in 1873 to English parents. By 1880, his hotel-owner father, A. Foster Boggis, had moved the family back to the UK, settling them eventually in Cumberland.[5] There, Boggis Sr became active in politics. A staunch patriot, if not jingoist, in 1889, he joined with others of a similar bent in splitting from the Liberal Party over the latter’s support for Irish home rule. For nearly a decade, he toured the provinces in what became known as the ‘Union Jack Van’, giving lectures on what he and his fellow-travellers saw as the folly of Irish home rule. His views were nothing if not trenchant.

Mr Boggis proceeded to argue that race and religion were answerable for a great deal that was laid at the doors of British misrule, and in proof of this proposition he gave some interesting details of his experience in Australia, where the average Celtic Irishman was only a very little in advance of his countrymen in Donegal. The lecturer closed by expressing his hope that the next election would result in another Unionist government, under one Imperial Parliament, one glorious flag, and one Empress Queen. (Loud applause.)[6]

In the early years, two of his sons, Percy and his older brother, Arthur, assisted their father, touring the country with him in the Union Jack Van, and working the equipment that Boggis used to deliver his lectures.[7]

Mr A. Foster Boggis of the LIBERAL-UNIONIST VAN will deliver LECTURES illustrated by a very powerful Lime-Light Magic Lantern Upon the Irish Question and Current Politics.[8]

Percy was in charge of operating the magic lantern, which would have involved the tricky task of controlling the flow of oxygen and hydrogen gases that, when combined and set alight, provided the heat that caused the block of lime (calcium oxide) at the heart of the apparatus to glow with an incandescent white light—the lime light of the name.[9] Still just a teenager, this delicate and highly dangerous job was Percy’s introduction to the world of stage lighting.

Boggis Sr would continue touring the country with the Union Jack Van until 1895 and then begin a second career as a travelling entertainer, playing phonograph records, presenting magic lantern shows, and, after the turn of the century, film shows of popular subjects and current events. He would also continue to lecture on political topics in support of Unionist and Conservative causes. This career would last until the outbreak of the First World War, and at least one of his sons would continue to act as his assistant.[10] However, this would not be Percy Boggis, as, in 1893, an event happened that changed the course of his life: Loïe Fuller brought her serpentine dance to London.

An entertainment more beautiful and entrancing in its class than she exhibits London has rarely seen. Her own share in it confined to clever dancing and a marvellous power of whirling diaphonous drapery into endless convolutions. The effect of this, however, when her figure is played upon constantly changing lights is indescribable. In turns she represents the serpent, the flower, the butterfly, and the white lady. Her sylph-like figure exhibited through the flying skirts which envelops her is indescribably beautiful, and the whole entertainment is simply magical.[11]

Although her reception was largely positive, there were dissenting voices, including among those people who, like Fuller’s imitators, recognised that the allure of the act was largely in its degree of invention, not its execution, something that could be easily replicated.

It is a pretty thing enough to see, and it does not look very difficult to do, though it must need a good deal of strength and energy on the part of the performer, who has to keep her arms in continual and very violent motion, in pulling and stretching her “sheeny vans”. But, after all, it is only a trick, and, when you come to think of it, a silly trick. It can scarcely be called dancing in any sense[…][12]

This, of course, Fuller recognised; it was why she took to patenting elements of her costuming and staging. However, in reality, there was little she could do to prevent others from copying her act, and the irony of her short but successful engagement in London in 1893 was that it left British audiences wanting more, an appetite that imitators were happy to sate.

In the summer of 1894, Fuller again travelled to London for a brief engagement, this time, appearing as entr’acte entertainment at no less than three theatres in a single evening (up from two an evening in 1893). This turned out to be overly ambitious, as dividing her time between three theatres left little rehearsal time for each of the acts, with predictable results.

The fair dancer did not find it all plain sailing on her first evening in London, for A SERIES OF CONTRETEMPS at each of the three theatres put her to the severest test. At the Trafalgar[...]the lights were not under proper control, so that the effects of colour produced by her celebrated lamps were some minutes in getting into proper focus[...]At the Strand, the band struck, and when Miss Fuller appeared to dance, only three or four of the musicians could be induced to make a sound[...]At Terry’s, where La Loie put in her third turn at eleven o'clock, the orchestra again gave evidence of insufficient rehearsal, and fairly disheartened by this untoward combination of events, the plucky little woman was fain to cut her program short, breaking down after her second dance.[…][13]

This second London engagement is of particular interest to us because, although it is not clear when Fuller first hired Percy Boggis, it seems likely that it was during this second London run. What we can be sure of is that it was Boggis who was in charge of the technical side of what would be Fuller’s largest production to date, Salomé, which premiered nine months later at the Comédie Parisienne in Paris.[14]

[...]the evening is brought to a close by Salomé, a biblical pantomime in which the celebrated American skirt dancer Miss Loie Fuller astonishes the public with a series of new and fanciful steps illuminated in a fantastic and highly artistic manner by the electric light. On the stage, and apparently inserted in the flooring of the Byzantine palace, are squares of looking-glass upon which Salomé twirls and dances before Herod, different coloured lights playing upon her gracefully pliant ligure, corsetless and very elementarily draped in the finest of white Indian silks that float out on every side, wonderfully manipulated by the danseuse.[15]

History records this production as a critical and popular failure.[16] This has been attributed to the piece requiring Fuller to appear in character in a revealing costume that, unlike the voluminous folds of her serpentine costume, showed her as she was: a woman older in age, shorter in stature, and fuller in figure than was normally associated with the Salomé of the Bible story.

That is as may be. What is undeniable is the praise that the new staging received. Making use of the arc lights that were, in this period, replacing lime lights, and a series of mirrors placed at angles to each other on the stage to have “…the effect of multiplying the reflections of one or more dancers performing in front of the said mechanism, thereby producing to the eye of the spectator an illusionary effect”, this latest production was Fuller’s most dazzling yet.[17]

Fuller had been working on elements of the staging she used for Salomé since 1893—her first patent application relating to the ‘looking glass’ effect was granted in France in January 1893. The role that Percy Boggis—in 1895, still aged just 22—had in helping to realise Fuller’s vision we cannot determine. Boggis would, in future years, produce innovations in stage lighting effects of his own, some of which he patented, and, as we have seen, although aged just 22, he was in charge of the technical side of the Salomé production, so was clearly recognised by Fuller to be usually capable for a man of such a young age. We might characterise him as an able apprentice and assistant to Fuller, someone willing and able to learn.

However, at the same time, subsequent events would hint at some discontent at his employment on Boggis’s part. Did he feel that he deserved more credit for the creation or realisation of the effects for Salomé than he received? Evidence from his later behaviour hints that he may have at least wanted to have been included in the billing. We can be certain that, when Salomé premiered, Fuller felt the need to remind rival acts that her effects were hers and were protected by patent.

WARNING TO MANAGERS. The Great ELECTRICAL EFFECTS and the CREATIONS produced in "SALOME" by Miss FULLER, now running to great success at the COMEDIE-PARISIENNE THEATRE, PARIS, are Fully Protected by her by all Rights of Patents in Great Britain, United States, France, and Continental Europe. Anyone Allowing or Infringing on same will be Prosecuted to the extent of the Law.[…][18]

Following the less-than-rapturous reception of Salomé, Fuller fled Paris for a rare extended tour of Great Britain, beginning at the Empire, Edinburgh, in June 1895, and culminating in an extended run at the Palace, Shaftesbury Avenue, London, across December 1895 and January 1896.[19]

Percy Boggis went with her. However, he would leave her employ before the end of the tour under disputed circumstances.[20] What is not in dispute is that, even before Fuller had returned to Paris, he had taken everything he had learned from her and used it to perfect a copycat act.[21]

Mdlle. JENNY MILLS, La Papillionne, In her latest Parisian Success, "La Danse Lumineuse," with all its Marvellous Electric Effect, supported by Mr. P. H. Boggis (Late Electrician to La Loie Fuller).[22]

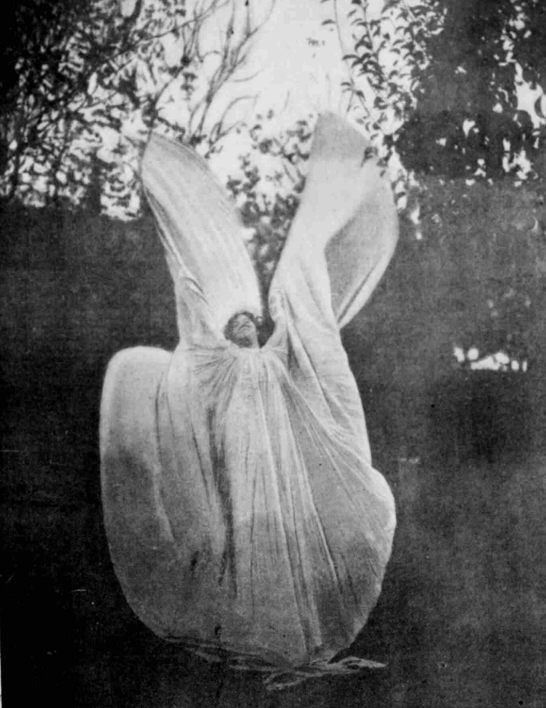

Jane “Jenny” Mills (1852–after 1909) was a fixture of the London and Paris variety stages, and had been for two decades by the time that Fuller debuted at the Folies Bergère. Partnered with her husband, sometime comedian, sometime bookie, Augustus Pegler (1849–1905), who went by the stage name Gus Westbrook, Mills enjoyed a 50-year career as a singer, dancer, comedienne, pantomime artist, and producer. She was born in Kensington, London, the daughter of William and Elizabeth Mills, but lost her father at a young age. She married Gloucestershire-born Augustus Pegler, who was described as a “vocalist” in the marriage register, in Notting Hill, London, in Dec 1870. The couple would go on to have two children who survived into adulthood, daughters, Rose Mills and Jane Pegler, both of whom followed their parents into the profession.[23]

Unquestionably, Mills’ greatest period of success was the decade or so she spent performing a copy of Fuller’s serpentine dance. This began with an engagement at the Grand Theatre in Brest in the summer of 1893 and continued after Mills and Westbrook/Pegler’s return to Britain in the autumn of that year, by which time Mills was billing herself as “Loïe Fuller’s rival”. At this point in Fuller’s career, her routine comprised her serpent, flower, butterfly, and white dances. Mills’ copycat act featured fire, flower, butterfly, and water dances. Photographs of the two performers in their billowing white silk costumes placed side by side (see gallery below) show just how little Mills attempted to distance herself from the original.[24]

Her 18-month partnership with Percy Boggis—and it was a partnership; she, Boggis, and another ex-Fuller-employee, George De Leclaire, split the proceeds three ways—brought to the copycat act new levels of fidelity to the original, incorporating Fuller’s latest technical innovations, realised by Boggis during his employment by Fuller. Thanks to the proceedings of a court case brought against Boggis and De Leclaire by a solicitor who helped support the two men after they split from Fuller, we have quite detailed knowledge of the events that led to the formation of the partnership.[25]

De Leclaire was the business manager for Fuller’s 1895 British tour, and Percy Boggis was the lead technician. The pair were with Fuller for the first four months of the tour as it criss-crossed the north of Britain. However, when the tour reached Liverpool in September 1895, they were let go. Fuller caught the pair trying to enter into some kind of business arrangement with James Kiernan, a Liverpool music hall proprietor, likely in connection with providing Kiernan with the secret to Fuller’s latest staging and lighting effects. With the plot exposed, Kiernan pulled out of the deal, leaving Leclaire and Boggis high and dry. Broke and stranded, the pair entered into an arrangement with George Neale, the Liverpool solicitor who had negotiated with Kiernan on their behalf, to find them another backer in return for a 10% share in the profits of any new act that Leclaire and Boggis developed for the next two years. This Neale duly did, finding someone who backed the pair to the tune of £150 to develop an act as part of their new three-way partnership with Jenny Mills—a sum that makes plain the extent to which they planned to transform Mills’ existing copy of Fuller’s act by providing her with access to Fuller’s latest lighting and staging effects, if the fact that they would be receiving two-thirds of the income of the act were not already proof enough.[26]

(Jumping ahead a little: the reason Neale later took Leclaire and Boggis to court was that the latter pair honoured the deal for the first 12 months, but declined to pay Neale any more money after that, being of the opinion that he had already received ample compensation for his efforts on their behalf. As part of this defence, they claimed that their relationship with Neale was that of solicitor and clients, not partners. The judge disagreed and found for Neale.[27])

An auditorium literally crammed to its utmost corner gave warmest welcome to Miss Jenny Mills, who created quite a furore by the picturesque, graceful, and chromotropic brilliancy of her "Danse Lumineuse," Mr P. H. Boggis being the electrician.[28]

The Mills–Boggis copy of Fuller’s act, managed by George De Leclaire, opened in Liverpool in December 1895—while, it will be remembered, Fuller was performing the original at the Palace in London. It appeared under the title that Mills (and her husband, Gus Pegler/Westbrook) had created for her more basic version of the act, La Danse Lumineuse; however, the wording of the billing and number of times reviews made mention of Boggis’s contribution to the lighting effects made plain that this was now a creative partnership between dancer and technician. We might hazard a guess from this that the lack of any equivalent billing under Fuller was at least one of the sources of Boggis’s discontent. Some of the reviews even went so far as to give Boggis the lion’s share of the credit for the appeal of the act, although, of course, good old-fashioned misogyny may have had something to do with that. Regardless, the act was a tremendous success.[29]

Alas, what Loïe Fuller made of all this, we do not know. Having let go Boggis and De Leclaire because of their attempts to sell her staging to James Kiernan, it seems hard to believe that she would be ignorant of the fact that they were using that same staging to elevate Jenny Mills from a mere copyist into a serious rival. The version of her act that Fuller performed on her 1895 tour of Britain comprised four dances: La Nuit (the night), La Firmament (the sky), La Blanche (the white), and La Lys (the lily). The Mills–Boggis version of La Danse Lumineuse also comprised four dances: a dance in black (the night), a dance in clouds (the sky), a butterfly dance, and a lily dance.[30] It could hardly be more blatant. This is perhaps evidence that Boggis’s greatest skill was in tweaking the effects just enough to escape charges of patent infringement, knowing that the dances themselves, as Fuller had found out to her cost, could not be copyrighted.

MISS JENNY MILLS, in her Parisian success, "La Danse Lumineuse," with its Splendid Electric Effects, by Mr P. H. Boggis. PARAGON, every Evening. Notice to Proprietors, Agents, &c. My Solicitors[...]are instructed to take prompt steps to protect my interests against all Persons using, adapting, or producing my Music, Title, 12 sheet Poster, or a Piracy thereof[...]My business relations with G. De Leclaire will terminate Saturday, June 5th, 1897. All contracts after this notice must be signed by me, otherwise I shall not recognise them.[31]

After 18 successful and lucrative months in which the three partners made over £2000 profit—a small fortune for the time—the Mills–Boggis act fell apart in the summer of 1897 in the fallout from the legal action mounted by George Neale against De Leclaire and Boggis. It seems, based on the wording of the first notices taken out by Jenny Mills after the departure for parts unknown of George De Leclaire, that her plan was to continue her association with Percy Boggis. However, within weeks, Boggis’s name had disappeared from Mills’ press, and Mills was sending out a general blast in the direction of anyone who might have designs on her act.

MISS JENNY MILLS, In Her Graceful and Artistic Production, DANSE LUMINEUSE. Paragon. Managers please note—The music of my act and the above title, La Dance Lumineuse, produced by me at Empire, Edinburgh, September 28, 1893, must be used by no other artiste, and my solicitor will take immediate steps against anyone infringing my rights.[32]

This claim to the name of the act tied to its original pre-1895 incarnation makes plain that Boggis was the real target of this warning. As events would show, after the end of the Boggis–De Leclaire–Mills business partnership and the departure of De Leclaire from the scene, Mills and Boggis had engaged in a tussle over ownership of the post-1895 version of the act. This was made plain by the announcement from Boggis in the trade press late in 1897: he had a new act ready to debut.

SOMETHING NEW, NOVEL, AND SENSATIONAL MDLLE. DE DIO. In her exquisite and charming production, " LA DANSE ILLUMINEUSE," Concluding with her startling FIRE DANCE, entitled "SHE," in the "FIRE OF LIFE."[..]P. H. Boggis, Manager.[33]

Mdlle. De Dio was the stage name of Florence Stafford Boggis (1876–1950), Percy’s new bride, the daughter of a Liverpool jeweller. At least two of Florence’s brothers, Frederick and Henry, also had connections to the stage, working as assistant electricians (technicians) as young men, with Frederick going on to manage a theatrical company; while, in time, two of her sisters would also become dancers in acts produced by Percy Boggis (of which, more below). However, it is not clear if this association of the Stafford family with the stage pre-dated Florence’s marriage to Percy Boggis or came about as a result. Regardless, we can be confident that Percy and Florence met during Percy and George De Leclaire’s extended enforced stay in Liverpool in late 1895, as the pair married in the summer of the following year, by which time Percy was on the road with the Jenny Mills act. He was 23, Florence was 20.[34]

Did Boggis have it in mind to replace Jenny Mills with his new bride from the start? It is clear from the fact that he named the new act La Danse Illumineuse, just two letters removed from the title of the Mills act, that he regarded the post-1895 version of the act principally his creation; by extension, he may well have seen the performer on stage as irrelevant to the success of the act (which again, may have had its roots in misogyny). In this respect, it is worth recalling the reviewer of Loïe Fuller’s 1893 London engagement who saw no artistry in the act, just physical strength and endurance. It is easy to imagine that, in Boggis’s view, all he needed to make the act work was his skill as a lighting technician and a woman, any woman, with the strength to wave her arms around for 15 minutes. Added to this, of course, by replacing a business partner with his wife, he would no longer need to split the proceeds from the act. Against this, from the perspective of Jenny Mills, she was the ‘face’ of the act—did the audience really care who was off-stage working the lights?

Of course, we need to keep in mind that this is two people arguing over ownership of a steal of someone else’s act. Indeed, Boggis’ ‘innovation’ of having Florence as De Dio appear as the character ‘She’ from H. Rider Haggard’s novel of the same name and perform a dance based on the climax of the novel, in which ‘She’ perishes in the ‘Flame of Life’, was yet another steal from Loïe Fuller, who had brought her own Fire Dance to London a few months earlier.

"La Loie Fuller” is back again at the Empire, with her new creation the "Fire Dance.” In the art of the lime-light, as applied to "serpentine dancing” Loie Fuller is facile princeps.[35]

Predictably, Jenny Mills would also soon add her own take on the fire dance to her act.

JENNY MILLS In the marvellous La Danse Lumineuse and the Fire Dance. See Jenny Mills in Flames. This Extraordinary Act has created furore in London and Paris.[36]

Being who they were, Boggis and Mills had no other Troy to burn.

MLLE DE DIO The Queen of Prismatic Dancers. Presenting a Gorgeous Production, the scenes of which are a succession of weird and beautiful visions of Dreamland.[37]

MDLLE. JENNY MILLS, the Great Fire, Serpentine & Classical Dancer. MDLLE. MILLS is recognised the world over as the Finest and Most Refined Fire Dancer now appearing on the Stage.[38]

Boggis and Mills would go on touring their versions of Fuller’s serpentine dance for a further decade. However, it must be acknowledged that by 1910, Jenny Mills was approaching 60 and a widow—Gus Pegler/Westbrook died in Lambeth, London, in December 1905. Nineteen Ten is also the year that Jenny Mills’ younger daughter, Jane Pegler, debuted a new act called “La Valti”. As a member of a troupe called, somewhat awkwardly, “The La Valtis”, La Valti also appeared on the same bill as Jenny Mills performing a similar “electrical dance”. By 1913, these two acts had morphed together to form ‘Mdlle Mills La Valti’ and her “bevy of beautiful girls”. We know that Rose Mills and Jane Pegler were living together and both performing as artistes at the time of the 1911 Census. La Valti’s manager, Arthur Haines, was also a member of the household, and he and Jane Pegler would marry in 1916. It seems possible to me that Rose Mills was a member of the Valti troupe and that the transition of Jane Pegler from La Valti to Mddle Mills La Valti marked Jenny Mills’ retirement from the stage. Mdlle Mills La Valti would become “Madame Valti” in 1914, but this would appear to mark the end of the Mills family as featured performers. Rose Mills was by this time 44, Jane Pegler, 40, and their mother, in her mid-sixties. I have been unable to determine dates of death for them.[39]

In 1910, Florence Boggis/De Dio was 34, two years younger than Jenny Mills' youngest daughter, and Percy Boggis was just a few years older. Across the decade, De Dio would perform up and down Great Britain and tour Australia at least twice, while Boggis would become the director of a stage lighting company and produce multiple musical revues—the latter a format that was particularly popular in the war years.[40]

Boggis would also dabble in artistic burlesque, producing a living statue act with Florence’s sister, Ada, who performed under the name “La Pia”. Boggis used lighting effects to cloak Ada/La Pia in just enough darkness to escape charges of public indecency, although this was still too risque for some boroughs. Ada as La Pia would, in time, tour the halls with her own version of the fire dance, almost certainly produced by Boggis; photographs from the time show that this act also leaned into the risque. A third Stafford sister, Pauline, would also take to the stage as Mdlle Naero, another fire dance act, no doubt also produced by Boggis. He was not afraid to milk a winning formula.[41]

The De Dio name would continue to appear on variety bills until the late 1920s.[42]

Like her English imitators, Loïe Fuller also moved towards managing other performers as the first decade of the new century turned into the second. In 1919, she returned to England for the first time since the end of the war. Alongside solo performances from Fuller, there were two ballets performed by a troupe she had choreographed. Fuller was now using projection screens, a precursor to her move into films in the next decade under the direction of her partner in business and in life, Gabrielle Bloch. In support of her continued interest in innovation in stage and electrical effects, Fuller set up a laboratory and befriended Marie Curie. In a similar vein, she opened a dance school and supported the early career of fellow modern dancer Martha Graham. She also became a champion of East Asian performing arts, promoting European tours by pioneering Japanese actresses Sada Yacco (Kawakami Sadayakko) and Madame Hanako (Ōta Hisa) and creating a hybrid Chinese traditional theatre dance drama performed by Chinese actors brought to Europe, at least according to Fuller, from Beijing. Everything she did caused a stir, and nearly everything she did spawned imitators. She died in Paris on New Year’s Day 1928.[43]

A NEW AND WONDERFUL LIGHT. Specially adaptable for Stage Lighting. THE VIOLET RAY Now Showing with Colossal Success in BRIGHTER LONDON REVUE AT HIPPODROME, LONDON. Pantomime Managers and Revue Producers requiring an absolute novelty WEIRD, WONDERFUL, and ARTISTIC should communicate with P. H. BOGGIS, The Creator of the Violet Ray.[44]

Percy Boggis would continue producing shows and developing new lighting effects into the 1930s, the most prominent of which was an ultraviolet light effect that he perfected around 1923. He and Florence retired eventually to Sussex. Percy died there in 1950, Florence in 1956.[45]

Loïe Fuller’s English imitators were but a pale shadow of the original, not least because they lacked that vital spark of originality. For all Percy Boggis’s undoubted gifts as a lighting designer and engineer, he was simply remixing colours from Fuller’s palette. But did the audiences who flocked to watch Jenny Mills, De Dio, and even La Pia and Mdlle Naero, care? Almost certainly not. As I have noted elsewhere, many middle-of-the-bill music hall acts were in effect tribute acts, “playing the hits” of acts higher up the bill. People were just happy to be entertained. Still, this is no reason to forget that they were imitators and not give credit where credit is due. To La Loïe Fuller.

Jamie Barras, January 2026.

Notes

[1] ‘Paris—Comédie Parisienne’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 5 April 1895.

[2] Sally R. Sommer, “Loïe Fuller.” The Drama Review: TDR 19, no. 1 (1975): 53–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/1144969. “THE SKIRT DANCE.” Scientific American 74, no. 25 (1896): 392–392. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26116768. See also: Albert A. Hopkins and Henry Ridgely Evans, “The Skirt Dance” in “Magic: Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, Including Trick Photography” (London: Sampson, Low, Marston and Company, 1897), frontispiece and pages 342–343. Available at archive.org: https://archive.org/details/magicstageillusi00hopk/page/n7/mode/2up, accessed 18 January 2026. See also the image of Fuller performing the Serpentine Dance: Frederick Whitman Glasier, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.58453, accessed 15 January 2026.

[3] https://redpoulaine.blogspot.com/2013/07/ida-pinckney-fuller-belle-epoque.html, accessed 15 January 2026. One of Fuller’s patents: https://patents.google.com/patent/US518347?oq=518347, accessed 18 January 2026. The dance was called the ‘serpentine dance’ because Fuller’s original costume design incorporated pictures of serpents; later, Fuller would abandon this in favour of a plain white silk costume.

[4] See Note 1 above.

[5] Biographical details for Percy Boggis: "England and Wales, Census, 1881",

FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2WM-FBFV), Entry for Alfred Boggis and Amelia Boggis, 1881, accessed 16 January 2026. Search of New South Wales birth records, https://familyhistory.bdm.nsw.gov.au/lifelink/familyhistory/search?10, accessed 16 January 2026. "England and Wales, Census, 1891", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:WTQZ-DPZ), Entry for Amelia Boggis and Percy Boggis, 1891.

[6] ‘Lavenham: Liberal Unionist Meeting’, Suffolk and Essex Free Press, 6 November 1889.

[7] Percy is recorded as a ‘lantern operator’ in his 1891 census return: see Note 5 above, final reference. He was at home with his mother on census night. His father and older brother were still on the road: "England and Wales, Census, 1891", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:WCMT-B2M), Entry for Alfred F Boggis and Arthur Boggis, 1891, accessed 16 January 2026.

[8] ‘Public Notices’, Cornish Post and Mining News, 27 February 1892.

[9] https://www.magiclanternsociety.org/about-magic-lanterns/illumination-used/, accessed 16 January 2026.

[10] ‘Haversham’, Buckingham Express, 1 June 1895; ‘Dorington’, Shrewsbury Chronicle, 9 October 1903; ‘The Young Brigade’, Manchester Courier, 12 March 1914.

[11] ‘Miss Loie Fuller’, Globe, 11 July 1893.

[12] ‘Gossip of the Week’, St. James’s Budget, 14 July 1893.

[13] ‘Loie Fuller in London’, Morning Leader, 15 May 1894.

[14] For Boggis’ role in the production, see Note 1 above.

[15] ‘The Comédie Parisienne…’, Lady’s Pictorial, 23 March 1895.

[16] Rhonda K. Garelick, ‘Loie Fuller and the Serpentine’, https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/loie-fuller-and-the-serpentine/, accessed 18 January 2026.

[17] Quote from Fuller patent, January 1895: https://patents.google.com/patent/US533167A/, accessed 18 January 2026.

[18] ‘Miscellaneous’, Era, 16 March 1895.

[19] Fuller begins UK tour in Edinburgh: ‘The Music Hall’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 7 June 1895. Ends UK tour in London: ‘Palace Theatre of Varieties’, Weekly Times & Echo (London), 26 January 1896.

[20] ‘A Liverpool Solicitor’s Claim’, Liverpool Mercury, 22 May 1897.

[21] ‘Amusements in Liverpool—Royal Alexandra’, Era, 21 December 1895.

[22] ‘Notices and Advertisements’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 16 March 1895.

[23] This information was arrived at beginning from the report of Gus Westbrook’s funeral: ‘Variety Gossip’, Era, 6 January 1906. Rose Mills was one of the attendees of the funeral. A search of death records for Lambeth for December 1905 shows that Augustus Pegler, aged 56, died in Lambeth in this quarter. A further search of marriage records shows that Augustus Pegler, “vocalist”, married Jane Mills in Kensington, London, in the final quarter of 1870; the marriage register gives the names of their fathers and their address at the time of the marriage. For Jane, this was 11 Bulmer Terrace (Kensington). The Mills family were living at that address at the time of the 1861 England Census, which supplies information on Jane’s age and place of birth. Augustus Pegler’s place of birth can be traced back from his year of birth. Further key records are the 1911 England Census return for Jane Pegler and Rose Mills, Lambeth, the 1901 England Census return for Rose Mills, and the Electoral Register entries for Augustus Westbrook, which tie the family to addresses in Brixton Road and Loughborough Road, Lambeth. Critically, Rose Mills was living at 158 Brixton Road in 1901, which is the address for Augustus Westbrook in the electoral register for that year. By 1905, Westbrook had moved to Loughborough Road. Jane Pegler and Rose Mills were both living on Loughborough Road, albeit at a different number, in the 1911 Census and their occupations are given as ‘artiste’. The year of birth for the 1911 Rose Mills and 1901 Rose Mills also align. Augustus Pegler/Gus Westbrook as a bookmaker: ‘The World Of Sport’, New York Herald (Paris Edition), 20 April 1891.

[24] Fuller dance sequence: see Note 12 above. Mills’s appearance at Grand Theatre, Brest, and dance sequence: ‘Notices and Advertisements’, Era, 25 November 1893. Photo of Mills in serpentine dance costume: ‘Miss Jenny Mills Giving the Serpentine Dancers a Lesson’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 15 December 1899. Comparable photograph of Loie Fuller: ‘Loie Fuller’ St James’s Budget, 27 January 1899.

[25] See Note 20 above.

[26] Account of court proceedings: see Note 20 above. James Kiernan: ‘Presentation to Mr. James Kiernan’, Liverpool Courier and Commercial Advertiser, 19 March 1897.

[27] ‘Action By A Liverpool Solicitor’, Liverpool Mercury, 31 July 1897.

[28] ‘Amusements in Liverpool—Royal Alexandra’, Era, 21 December 1895.

[29] Boggis in the act’s billing: see Note 22 above. Boggis mentioned in reviews: see, for example, ‘The Empire, Cardiff’, South Wales Daily News, 2 June 1896. Boggis receiving large share of credit: ‘Sheffield—The Empire’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 8 May 1896.

[30] Fuller’s dance sequence for 1895 British tour: ‘La Loie Fuller at the Empire’, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 12 September 1895. Mills’ dance sequence in La Danse Lumineuse with Boggis: ‘Miss Jenny Mills at the People’s Palace’, Dundee Courier, 9 January 1897.

[31] ‘Advertisements and Notices’, Era, 5 June 1897.

[32] ‘Notices and Advertisements’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 25 June 1897.

[33] ‘Notices and Advertisements’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 5 November 1897.

[34] Biographical information for the Stafford family from England Census returns. "England and Wales, Census, 1891", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:7STB2T2), Entry for Richard Stafford and Elizabeth Stafford, 1891; "England and Wales, Census, 1911," database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XW4X-3QN), Frederick John Stafford in household of Elizabeth Stafford, Finchley, Middlesex, England, United Kingdom; "England and Wales, Census, 1901", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch .org/ark:/61903/1:1:X9VT 7H5), Entry for Richard Stafford and Elizabeth Stafford, 31 Mar 1901; "England and Wales, Census, 1901", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch .org/ark:/61903/1:1:XSFS TDC), Entry for Percy Boggis and Florence Boggis, 31 Mar 1901. Years of marriage and death for Florence Stafford Boggis, search, Births, Marriages, and Deaths, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/search.pl, accessed 19 January 2026.

[35] ‘Loie Fuller at the Empire’, St James’s Budget, 24 September 1897.

[36] ‘Events to Take Place’, Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal, 25 December 1897.

[37] ‘Amusements, &c.’, Portsmouth Evening News, 26 September 1910.

[38] ‘Public Notices’, Leamington, Warwick, Kenilworth & District Daily Circular, 16 August 1910.

[39] “La Valti” with “A. Haines” as manager: ‘La Valti’, Era, 27 August 1910. “Jenny Mills” and “The La Valtis”: ‘Notices—Olympia’, Jersey Evening Post, 27 August 1910; “Mdlle Mills La Valti”: ‘The Palladium’, Lichfield Mercury, 13 August 1913. Mills, Pegler, Haines living together 1911 England Census: "England and Wales, Census, 1911", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XW5Q-DVN), Entry for Jane Pegler and Rose Mills, 1911. Pegler–Haines marriage: "England and Wales, Marriage Registration Index, 1837-2005," database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:26F7-134), Jane Pegler and null, 1916; from "England & Wales Marriages, 1837-2005," database, citing 1916, quarter 3, vol. 1D, p. 623, Lambeth, London, England. Madame La Valti: ‘Theatre Royal Guildford’, West Surrey Times, 3 April 1914.

[40] De Dio in Australia: ‘Mdlle De Dio’, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 November 1909; ‘De Dio Returns’, Daily Herald (Adelaide), 25 August 1914. Percy Boggis, stage lighting company: ‘Theatre Lighting’, Era, 5 October 1912. Revues, for example: ‘London Theatre of Varieties’, Era, 18 March 1914.

[41] Ada “La Pia” Stafford and Pauline “Mdlle Nero” Stafford: Michael Killgarriff, ‘Grace, Beauty, and Banjos—Addenda’, http://www.michaelkilgarriff.co.uk/grace.htm, accessed 20 January 2026. La Pia and public decency: ‘Living Statuary’, Birmingham Mail, 4 May 1907. La Pia fire dance: ‘The Lady of the Flames’, The Bystander, 16 March 1910. Mdlle Naero fire dance: ‘Mdlle Naero’, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 14 March 1912.

[42] De Dio in 1929: ‘Amusements. Stage and Screen at Northampton’, Northampton Chronicle and Echo, 21 December 1929.

[43] ‘Loie Fuller’s Colour Schemes’, The Globe, 25 August 1919. For Gabrielle Bloch and Marie Curie, see Note 16 above and: https://lizleeheinecke.com/when-loie-met-marie-marie-curie-and-loie-fuller-fullers-documented-interactions/, accessed 20 January 2026. I cover the connection between Fuller and Sada Yakko and Madame Hanako, here: https://www.ishilearn.com/staged-identities-fireflies, accessed 20 January 2026. For Fuller’s Chinese drama, see: ‘The Dragon of Wrath’, London Evening Standard, 8 December 1910.

[44] ‘Effects’, The Stage, 30 August 1923.

[45] Years of death for Percy and Florence Boggis: search, crosschecked by age, Births, Marriages, and Deaths, https://www.freebmd.org.uk/search, accessed 20 January 2026.

Loïe Fuller performing the Serpentine Dance: Frederick Whitman Glasier, photographer. Image created by the Library of Congress, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.58453. Public domain.

Loïe Fuller, St James's Budget, 27 January 1899. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

Miss Jenny Mills, Music Hall and Theatre Review, 15 December 1899. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.

The stage lighting Loïe Fuller designed for her serpentine dance. Albert A. Hopkins and Henry Ridgely Evans, “The Skirt Dance” in “Magic: Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, Including Trick Photography” (London: Sampson, Low, Marston and Company, 1897), frontispiece. Public domain.

Image from one of Loïe Fuller's patents. https://patents.google.com/patent/US518347?oq=518347

Florence "De Dio" Stafford Boggis. Illustrated Police Budget, 27 August 1898. Image created by the British Library Board. No known copyright holder.