Health, Friendship, and Baseball, Part III

Jamie Barras

CARDIFF WORKERS’ SPORTS CLUB. It has been decided at a meeting of Spillers and Bakers (Limited) workers, Cardiff, presided over by Mr. S. Potter, to resuscitate the athletic club, which was closed for the duration of the war […] It was decided to hold another meeting this summer and to re-instate the various sections of sport, including cricket, Rugby and Association football, baseball, and swimming.[1]

With the end of the First World War, US forces began to leave South Wales. The last game between US teams in Cardiff reported in the newspapers took place in March 1919, at Cardiff Arms Park, between US Navy ‘Headquarters’ and ‘Crew’ teams; the Crew team won 9–4.[2] By then, moves were already afoot to, in the words of the local newspapers, ‘resuscitate’ the game under the English code in South Wales. The WBA held its first post-war meeting on 14 May 1919; 40 clubs had already indicated that they would take part in the revived league.[3]

Meanwhile, the Newport Baseball Club held its first post-war meeting on 10 May 1919 and played its first game, against Splott US, on 17 May. Jack Wetter was back from the war, his brother Edmond was confirmed as team captain, and another brother, Frank, was also in the team. Newport would prove dominant in the 1919 season, winning the championship.[4] One decision made at the 10 May meeting was to ban ‘dolly’ bowling. I will return to this below.

As the Newport game shows, Splott US was also back in action. Indeed, the 1919 season was populated with many of the clubs that had played in the last season before the war, including Penylan, Grange Albion, Pill Harriers, the Gasworks, and Grange Y.M.C.A. A notable addition (for one season only) was the ‘14th Cardiff Old Comrades’, a team formed of Cardiff-based veterans of the 14th (Service) Battalion of the Welsh Regiment, which was known as the ‘Swansea Pals’ as many of its early volunteers were from Swansea. Noticeably by its absence was Grange, the team that had dominated the pre-war game (it would, however, return for the 1920 season).[5]

However, the above should not be taken to mean that it was business as usual. The opposite was very much true. This period in the history of the game in South Wales was one of change, and it is these changes that I will focus on here.

The first concerned styles of play.

For the benefit of the uninitiated, it may be explained that “dolly” bowling is slow, lob bowling. All baseball bowling is underhand […] and the ball must pass over the batsman’s crease above the level of his knee, below the top of his head. Most bowlers send the ball down fast, with a low trajectory […] but the “dolly” bowler pitches the ball up in the air. It travels slowly, and comes down steeply like a ball dropping from the roof of a house.[6]

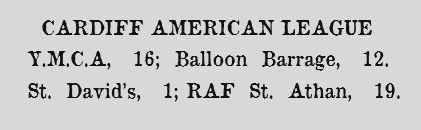

The decision by the Newport club to ban ‘dolly’ bowling, although not a rule change, reflected the sense post-war that the game needed to change. Banning ‘dolly’ bowling, like most of the changes across the next ten or so years, was aimed at making the umpire’s life easier, in this case, to make it easier to see if the ball reached the crease below head height. Controversies arising from contested decisions were a perennial problem in games under the English code, exacerbated by the amateur status and nature of both players and umpires. Thus, in 1927, a rule was introduced that gave the batter no runs if they were caught out. Under the English code, a batter/runner scored a run every time they rounded a base (called ‘posts’ under the English code); before the 1927 rule change, umpires had to award a number of runs equal to the number of bases the runner had rounded before the catch being made. However, they could not be looking at two places (the locations of the fielder and the runner) at once, and errors were made. A further rule change, introduced in the EBA in 1920, reduced the number of runs that a runner scored by rounding all four bases (a ‘home run’ under the American code; a ‘four’ under the English code) from four to two. For obvious reasons, the latter rule did not last long.[7]

There was a range of possible solutions to these problems available, but, I believe not coincidentally, the solutions chosen brought the game under the English code closer to that under the American code. In this, we can see the influence of players and officials being able to witness games played under the American code by American teams during the war years.

Wrapped up in these changes in the style of play were changes in governance.

WELSH BASEBALL. ARRANGEMENTS FOR THIS SEASON. […] The organisation of the Welsh Baseball Association has been re-modelled on the soundest possible lines, with a view to increasing interest in the game, particularly in districts which have not, as yet, come within the scope of the Association. One of the changes was the creation of a Welsh Baseball Union—a central authority organised on similar lines to the Welsh Rugby Union. This is a new departure, which, it is believed, will be good for the game in Wales.[8]

Modelling itself on the Welsh Rugby Union (WRU), the Welsh Baseball Union (WBU) came into being in April 1921 to take charge of the game at all levels, from the newly envisaged ‘schoolboy league’ (to ‘grow’ new players) up to the England vs Wales Baseball Internationals. Under this umbrella, sat the Glamorganshire (Cardiff) Baseball Association and Monmouthshire (Newport) Baseball Association, with both associations running their own district leagues in addition to their top teams playing in the renamed Welsh League. Ted Diment, the long-time official with the Splott US club, was the WBU’s first vice-chair. One of the new Union’s stated aims was to strengthen links with the EBA in Liverpool with a view to reforming and standardising the code and improving the training of umpires, etc.[9]

By August of 1921, the Liverpool newspapers were reporting that the EBA and WBU had entered ‘upon a kind of amalgamation’ to be called the ‘British Baseball Union’. However, this announcement proved premature. In fact, it would be another 7 years before the two associations would, rather than merge, create a body through which they could work together on shared priorities, the International Baseball Board. Although this may have been with the intention of unifying the code in the two countries, ultimately, it would only coordinate the rules and procedures of the playing of the England vs Wales Baseball Internationals.[10]

Still, in terms of both participation and spectatorship, the game was in a period of growth. The next significant development would be the emergence of the women’s game.

Mr Emlyn Jones, general secretary, reported that when he took office thirty years ago, there were only 22 teams attached to the organisation, whereas now there were 91, excluding boys’ and ladies’.[11]

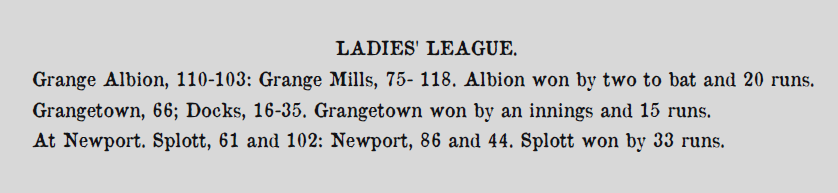

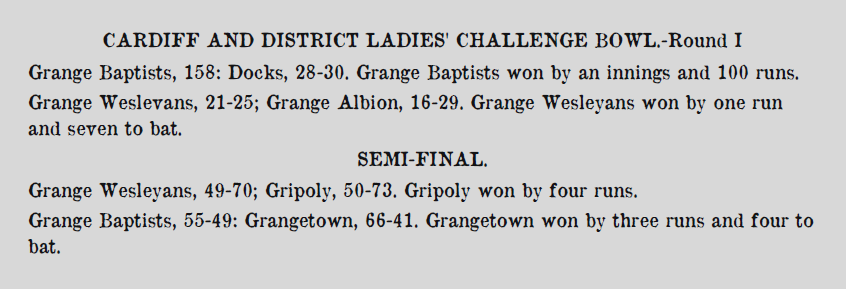

Within two years of its founding, the WBU had organised its first women’s league, the ‘Cardiff Ladies’ League’, which commenced in May of 1923. It also initiated a challenge cup, the ‘Cardiff and District Ladies’ Challenge Bowl’, with the first round being played in July of 1923. Splott University Settlement was one of the founding teams. The other teams were also a host of familiar names: Grange Albion, Channel Mills, Gripoly Mills, Docks, Grange, Grange Baptists, Grange Wesleyans, and Newport. Grange Wesleyans won the league, and Grange the Challenge Bowl.[12] It is worth noting here that in 1927, the ‘Cardiff Ladies’ Baseball Union’, the body that ran the league, held what was described on one newspaper report as its ‘sixth annual meeting’; however, this may have been an error on the journalists’ certainly, no mentions in the press of a league can be found before 1923 (although ladies’ teams unquestionably existed before that date).[13]

I have written about the birth of women’s baseball in England under the American code elsewhere,[14] and there are strong parallels with that phenomenon to explore here. Not least in that the women’s game under both codes emerged in the decade following the end of World War One.

Just as with the men’s game in South Wales, the list of teams in the Cardiff women’s league ran the gamut of institutions that promoted physical recreation amongst their workers and members. Chapel Sport played a strong role, as the presence of the Nonconformists and the Splott US teams shows—with the Splott US team benefiting from the added boost of the settlement having, from its earliest days, a women’s section (led by Una Burrows). However, running in parallel with this was the strong association between women in the workplace and sports that dated, famously, from the War, when women replaced men in key industries.

This also represents the strongest parallel with the game under the American code, where it was women’s sections of company recreation clubs that led the way, albeit, in that case, beginning with companies that were subsidiaries of American concerns (Kodak prime amongst them) that already had women’s baseball sections at their North American plants.

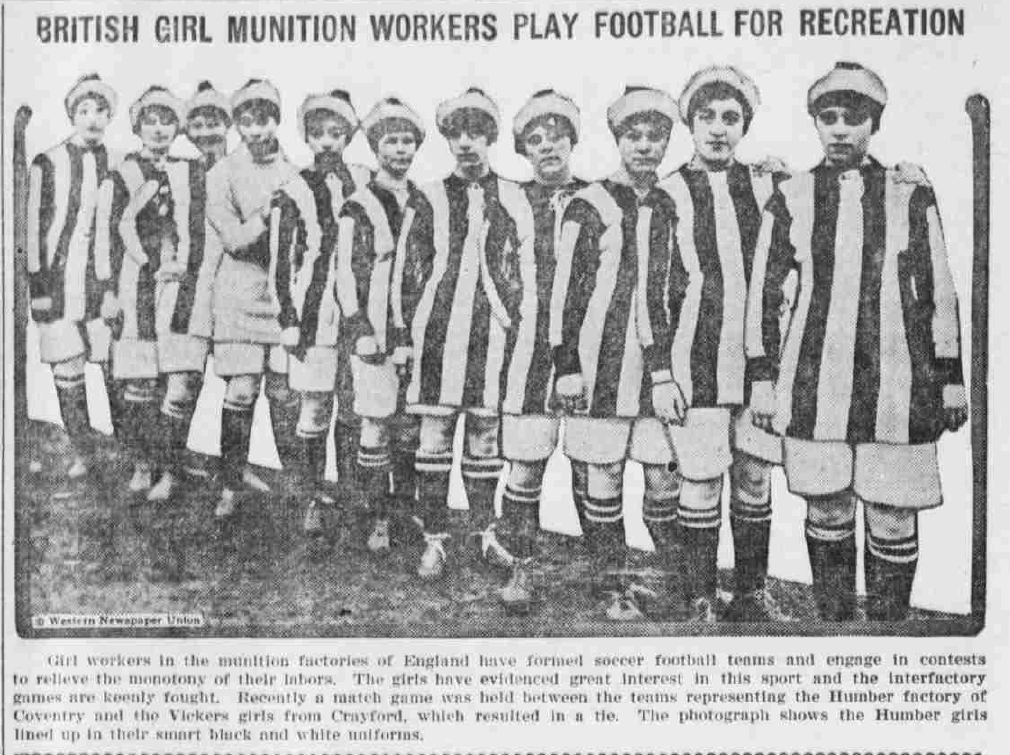

Alas, as ever with women’s sports, there is a dearth of accounts in the historical record of the early days of women’s baseball in South Wales. However, it is instructive in lieu of such accounts to examine the case of women’s football, which has been the subject of increasing scholarship in recent years.[15] By 1918, there were 1 million women in Britain working in the munitions industry alone. Dubbed ‘munitionettes’, many of these women embraced the opportunities offered to them by their employers to join company recreation clubs and learn and play the games that had previously been the preserve of male employees. Football was far and away the most popular sport among the munitionettes, and, initially, the Football Association seized on this, encouraging munitionette teams to stage games against each other for charity in support of prisoners of war and military hospitals. From this developed leagues with upwards of 150 teams.

It is easy to see that we could replace ‘football’ with ‘baseball’ in the account above and be describing the likely situation in the factories and mills of South Wales between 1914 and 1919 (when the men returned to their jobs, displacing many of the women employees). The evidence in support of this is the presence in the 1923 league of the Channel Mills, Docks, and Gripoly Mills teams. Critically for our story, however, is that the stories of women’s football in England and women’s baseball in South Wales diverge after the end of the war. Famously, by 1921, the Football Association had carried out a volte-face and banned women’s football after encouraging it in wartime. Conversely, the WBU would embrace the women’s game. Again, it is hard to see this and not see the influence of Nonconformism in South Wales, the openness of Chapel Sport to the participation of women, and the top-to-bottom blue-collar nature of the WBU. This flies in the face of not only the treatment of the women footballers in England, but also women in the workplace, with hopes for an equal status to men, with ‘the Right to Work, the Right to Live, and the Right to Leisure’, nurtured in the war years, being largely dashed as soon as men in the armed forces began to be demobbed.[16]

We can extend this argument by contrasting women’s baseball in England under the American code, which outside of its heartland of the recreation clubs of companies like Kodak would face a continuous battle for respect in the face of the men who controlled the game, men who viewed the women’s game as little more than a promotional gimmick to bring in [male] punters before the serious business of the day—men’s games—got underway. Thus, there would be a women’s league in London in 1936 and 1937 (which I will cover in the next part of this series), and Hawk-Eye would take part under the name ‘Kodak’; however, their opposition were teams with names like the ‘West Ham Hammerettes’ and ‘Romford Honey Bees’,[17] which is indicative of how the ‘professional’ London baseball clubs, in contrast to the Kodak recreation club, treated their women’s baseball sections.

The worlds of women’s baseball under the American and English codes would come together when, in 1931, Eddie Lynch, coach of the pre-eminent women’s team playing under the American code, the Kodak Hawk-Eye, advertised for an opponent for the Hawk-Eye to determine what he entirely spuriously dubbed the ‘European Women’s Baseball Championship’. The challenge was accepted by the St Dyfrigs team of Cardiff. The match was played on 31 August 1931, and the Kodak team won 10–8, which tells us, as we might expect given that the challenge had been issued by the Kodak team, that the game was played under the American code.[18] That same year, seven years after the WBU had established a women’s league, the EBA in Liverpool finally followed suit.[19]

I will return to the Kodak Hawk-Eye and Eddie Lynch in the next part of this series.

Alas, that dearth of contemporary accounts that devil women’s sports before the modern era comes into play here, too, despite the strength of support for the game in terms both of participation and spectatorship that lasted decades. Several accounts state that the first women’s baseball international [between Wales and England] was played in 1926; however, I can find no mention of this in newspapers of the time.[20] As ever, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence; however, this does demonstrate that there is a need for more research into this topic.

I would like to finish this brief description of the women’s game in South Wales in this period by presenting two rosters from a game played during the Cardiff women’s league’s second season (1924) and using these to try to identify some of the players.

“A” and "B" teams in the exhibition game of the Cardiff and District Ladies' Baseball League at Splott Park this evening:-

“A” Team: G. Sinith (Wesleyans, capt.), T. Martin (Gripoly), G. Miller (Baptists), H. Royle (Baptists). F. Coles (Gripoly), N. Galpin (Grange). F. Curthoys (Wesleyans), O. Smith (Baptists), O. Parsons (Baptists), I. Royle (Baptists), and A. Stevens (Albions). Reserves: O. Jones (Albions) and R. Maylard (Gripoly).

“B” team: A. John (Baptists, capt.). H. F Pugsley (Gripoly), D. Blackler (Grange), O. Evans (Albions), H. Davies (Baptists), R. Martin (Albions), G. Horwood (Grange), M. Marshall (Albions), M. James (Wesleyans, M. Escott (Gripoly), and E. King (Gripoly). Reserves: D. Foulkes (Wesleyans) and E. Peterson (Albions).[21]

Of note here is ‘H. Royle’. This is almost certainly a 19-year-old Hilda Royle (1905–1993), described in later years as a pioneer of the women’s game.[22] That makes ‘I. Royle’, Irene Royle (1909–1994), Hilda’s sister, who was just 14 years old at the time of this game. The Royle family lived in Grangetown, which supports the identification—‘H Royle’ and ‘I Royle’ both played for the Grange[town] Baptists women’s baseball team. In 1921, Hilda was working as a typist; we can suppose that this was still her job here in 1924. Thanks to a contribution made by one of her descendants to the Ancestry.com platform, we can enjoy a remarkable photograph of early women’s baseball in South Wales in the form of a photograph of Hilda Royle, circa 1926, caught mid-pitch, wearing a pinafore dress and a tennis player’s sun visor and hairnet combination; the epitome of the Chapel Sport devotee.[23]

Following the same logic, we can also suppose that the other women in the rosters would have been Grangetown residents. Armed with this information and the 1921 Wales Census, we can tentatively identify Nelly Galpin (1908–?). Nelly’s two older sisters were working as rope spinners in 1921; we can suppose that this was the job that Nelly was doing here in 1924. It will be remembered that the local ropeworks contributed a men’s team to the pre-World War One league. Two more possible identifications are Florence Curthoys (1905-1980), a draper’s assistant, and May Escott (1906–?), a domestic servant.

We can immediately see that many of these women were young, and most were in paid employment. Research is ongoing to discover the full stories of Hilda Royle and these other pioneers of the women’s game in South Wales.

The American Legion has invited the English and Welsh baseball teams, who are playing at Stratford on Saturday, out to see the game at Stamford Bridge, when American baseball will be shown at its best and can be compared with the Welsh game.[24]

The 1920s and 1930s represented a golden period in baseball under the English code in South Wales in terms of participation from players and spectators. In August 1926, 12,000 fans turned out at Cardiff Arms Park to watch Wales beat England by an innings in that year’s Baseball International. A week earlier, listeners to BBC Local Radio could have heard former international and organising secretary of the WBA, William H. Boon, preview the match on his regular Saturday night ‘Baseball Prospects’ show.[25]

One survivor from this period is a photograph of the Splott University Settlement Baseball Club from 1928, showing the men’s and women’s teams sitting together.[26] By this date, the settlement itself has closed its doors for good (the settlement buildings had been taken over for use as a hospital during the war and were sold to the RC Archdiocese of Cardiff in 1923[27]). However, the members of the settlement had by this time internalised its ideals, and the baseball club had become the embodiment of the ideals of health and fellowship that the settlement had been set up to foster. In effect, the settlement had served its purpose.

Meanwhile, both the WBU and EBA continued to have high hopes of popularising the game beyond its two centres of Liverpool and South Wales. As the quote above shows, they even staged two exhibition games in London, arguably the home of the game played under the American code (the first, on 9 June 1924, at Stratford, East London, was won by Wales, the second, the following day at Tufnell Park, North London, by England).[28]

The American Legion Post in London, North American army veterans who staged weekly games under the American code in West London in this period, extended a rather back-handed invitation to the Liverpool and South Wales teams to come and watch one of their regular games. (That same year, the Legion would found the Anglo-American Baseball Association (AABA), which would, within a few years, become a supporter of the Kodak Hawk-Eye team.[29])

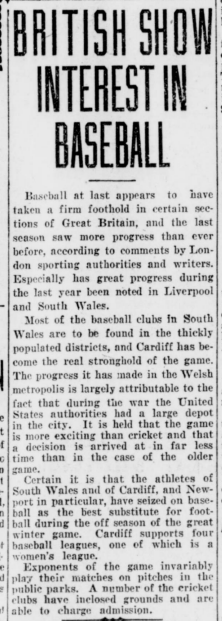

The description of the game that the England and Wales teams played in the report about the invitation from the American Legion—‘the Welsh game’—was incorrect, as the game began in Liverpool; however, this reflected the perception of the game to outsiders and the fact that the game was much bigger in South Wales during this period than in its birthplace:

The venue for the annual baseball internationals alternated between Cardiff and Liverpool; the year before 12,000 people watched the 1926 game at Cardiff Arms Park, just 5000 watched the 1925 game at Fairfield in Liverpool. For the 1924 game in Cardiff and the 1923 game in Liverpool, the attendances were 10,000 and 6000, respectively. It is not too much to say, based on this, that the game in South Wales enjoyed roughly twice the support of that in Liverpool, despite Liverpool having nearly three times the population of Cardiff and Newport combined at this time (1921 Census: Cardiff, population, 200,000; Newport, 92,000; Liverpool, 802,000). (It is worth noting that England regularly won at home in this period, as it did in 1923, so it was not a matter of no one wanting to watch their home side lose.)[30]

This, of course, reflects the diversity of the population of Liverpool, a city of many peoples and faiths, and the integration of the wider Liverpool sport scene with that of the rest of England; the conditions simply didn’t exist there, as they did in South Wales, with its much more homogenuous population (largely Welsh, largely Nonconformist) and strong national identity, for a single sport to corner the market.

One consequence of baseball under the English code being such a niche sport in Liverpool was that, even in the heady days of the 1920s and 1930s, when it was enjoying its greatest period of success, the EBA subjected itself to much more introspection as it searched for a way to put itself on a firmer footing. This was a recipe for internal conflict arising from competing visions for the way forward, and this would, in turn, lead to the next challenge faced by the game in South Wales: the return to the national stage, at a scale not previously seen, of the American game.

As if major league baseball wasn't having a tough enough time nowadays, what with so many domestic problems to solve, it seems that John Moores, "patron" of the English Baseball Union, is about to interview the leaders of the American organized game with a view to promoting international relations, good-will and, most fearsome item of all, competition.[31]

John Moores was a Liverpool-based businessman and head of the Littlewoods Group who had made his fortune in sports betting and then diversified into mail order shopping.[32] The ‘English Baseball Union’ (EBU) was a breakaway organisation created in Liverpool in January 1932 following turmoil within the EBA over the previous few months.

Trouble began in October 1931 when the leadership of the EBA, in response to existing conflict, principally on whether to continue efforts to expand the game beyond its Merseyside heartland or concentrate on shoring up support locally, introduced a rule that would reduce the number of officers of the association. This, not coincidentally, would concentrate power in the hands of the men at the top of the organisation, long-standing chairman A.J. Bailey and secretary H. Deakin. At the association’s annual meeting, held just after this rule change, Bailey and Deakin, expecting to assert their new authority, instead found themselves failing to be re-elected for a further term. They were replaced at the top of the association by H. Kennard and G.A. Cannell, organisers of the Liverpool and English leagues, respectively. Within weeks, Kennard and Cannell were themselves ousted from their posts following a vote of no confidence. In response, the two men and their supporters resigned from the EBA and, in the New Year, launched a competing association, the EBU, populated with some of the strongest teams in the EBA leagues.[33]

Moores became a patron of the EBU, sponsoring one of its cup competitions. When, in March 1933, he travelled to America, most likely on business connected to the mail order catalogue business he launched in 1932, he carried with him a letter from the EBU to the heads of the National and American Leagues (John Heydler and John Harridge, respectively) proposing ‘international games with England, Ireland, and America’.[34]

It must be understood that at present the two countries play under different codes, but the main principles of the game are similar and there is no apparent reason why agreements cannot take place. America has taken main laurels from this country in practically every form of sport and we believe that we have amateur baseballers in Liverpool who can give America's best a live game.[35]

The reference in the letter to the two countries playing under different codes ‘at present’ is ambiguous, suggesting that this may not always be the case. However, we can be certain, given subsequent events, that it was not the EBU’s intention to suggest that it would be willing to abandon the English code. Regardless, although Moores had agreed to act as an ambassador for the EBU, once in the US, he underwent a Damascene conversion as a result of getting to experience a game under the American code at the scale at which the American game could mount it, with all the accompanying spectacle (and revenue). On his return to Liverpool in the summer of 1933, he organised a meeting with representatives of both the EBU and the EBA, and there, told them that he was ‘all out for 100 per cent. American baseball, and that if they decided to form a league, he would give them every support’.[36]

The language makes plain that this was Moores acting on his own initiative, not following through on any proposal that the EBU had asked him to take to America. Added to this, a few years later (1937),[37] Moores would give a highly selective version of the events of that Spring and Summer in which he claimed to have met John Heydler by accident in a New York Hotel. In this account, Moores neglected to mention that one of the goals of his US trip was to meet Heydler in his role as ambassador for the EBU—in fact, he even acted as if, although aware of the English game, he had no connection to it and thought little of it. This version of events is the one that has been transmitted down to the present day. As I have shown here, it is so selective as to be effectively untrue.

Whatever the true sequence of events, as a result of Moores being willing to throw his considerable financial resources behind relaunching the American game not just in Liverpool but right across the country, a number of the Liverpool clubs switched to the American game, forming the nucleus of Moores’ endeavour. I do not intend to tell the full story of the Moores’ leagues here, I have already covered many aspects of the ‘professional’ Moores leagues elsewhere,[38] and will cover the amateur leagues in the next part of this series; instead, I want to focus on what this meant for the game under the English code in South Wales. To do that, we first need to look at baseball in the RAF.

The R.A.F. means to make baseball a compulsory training. Wing-Commander Babington, in charge of the training school at Halton, Bucks, is having two star teams down from London on Wednesday to play an exhibition game before his men. After that the boys go ahead and play themselves with instructors to put them wise.[39]

RAF Halton in Buckinghamshire was home to the No. 1 School of Technical Training, the primary training centre for RAF groundcrew. By the mid-1930s, it hosted over 4000 aircraft apprentices. As might be expected, it had an extensive sports programme with team sports for every season. In 1936, at the initiative of station commander and school commandant Wing Commander John Tremayne Babington, it added American baseball to its summer sports programme. Contrary to reports in the London newspapers, such as the one above, the playing of the game was not compulsory; it was simply one of a number of summer sports, cricket being the most prominent, available for the apprentices to play. One of the two ‘star teams’ down from London for the game designed to introduce the sport to the apprentices was the Streatham-Mitcham Giants; the name of the other went unreported.[40]

By the following summer, the camp had an Inter-Squadron baseball league with 12 teams. In early July of that year, two amateur London teams, the Ilford Nomads and Ilford No Varys, visited the camp only to both be bested by the apprentices. That story grew in the telling, and by August, the London newspapers were reporting that the camp had 60 teams and the apprentices had recently beaten two teams from the [professional] London Major Baseball League. The following summer, it was the turn of the amateur American team that was in England to play in what would later be billed the first Amateur World Series to pay a visit to Halton.[41]

Critically for our story, by 1938, the game had been adopted by other RAF technical training schools, prime amongst them, No. 4 School of Technical Training at RAF St. Athan in South Wales. The National Baseball Association (NBA), the body founded by John Moores to run the American game in Britain, now had a pool of players available to help it launch a third attempt to establish the American game in South Wales.

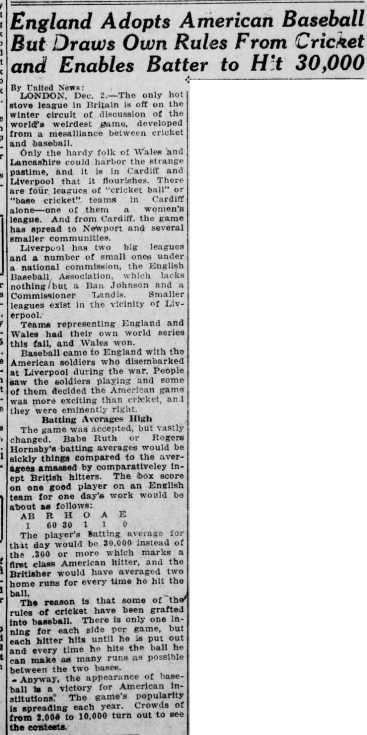

If everything works out according to plan an American baseball test match between England and America will be staged in Cardiff this year. Already eight teams have signified their intention of joining the league to be formed under the auspices of the National Baseball Association, and now the inauguration of a second division is being contemplated.[42]

What would become known as the ‘Cardiff American Baseball League’ (or simply ‘Cardiff American League’) began to take shape in March 1939 under the watchful gaze of Andrew McGraw, a veteran NBA organiser, sent to Wales for the purpose. Former Welsh international (under the English code) Freddie Fish, at the time, the holder of the record for the most successive home runs in a game, was trumpeted as having joined in the effort (under the rather nebulous title of honorary ‘assistant coach for the South Wales area’).[43] When it finally launched in May, two of its seven (not eight) teams were from RAF formations: RAF St Althan and the County of Glamorgan Barrage Balloon Squadron (which, strictly speaking, was part of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force). The other teams were the Central Y.M.C.A., Penylan, the Lumberjacks (timber merchant employees), St David’s, and the Mail & Echo (employees of the Western Mail and South Wales Echo newspapers). The RAF St Athan team topped the league at the end of the season.[44]

Arguably, the real value of the RAF teams to the NBA was that they provided a pool of players who could be used to try to excite interest in the American game in other parts of the principality. In addition to its games in the Cardiff American League, in the summer of 1939, the RAF St Athan baseball section, which was led by a Canadian, Flight-Lieutenant A.R. Hughes MBE, played exhibition games on behalf of the NBA in Newport, Mountain Ash in the Rhondda Valley, and Blackwood in Gwent. The Mountain Ash game was against a team formed of the best of the rest of the players from the Cardiff American League, including Freddie Fish.[45] The Newport game was against a team from Birmingham led by ‘Sid’ Bissett (Donald Alexander Bissett (1905–1992)), whose career I have already touched on elsewhere,[46] and whom we will meet again in the next part of this series. The Blackwood game was two St Athan teams playing each other.

Clearly, the NBA was intent on making the game stick in Wales this time around. Alas, it was not to be. On one level, the conditions were simply not right locally for the game to make an impact. In Liverpool, it had benefited directly from divisions within the EBA—indeed, arguably, the NBA would not have existed without those divisions. However, in South Wales, there were no such divisions, and the game under the English code was enjoying more success than it had ever done before. This was the era when Welsh Sports Hall of Fame inductee Ted Peterson (1916–2005) (the only inductee inducted for his baseball prowess) was coming into his own. The game was at close to its peak when the NBA launched the rival Cardiff American League. It was always going to be an uphill struggle.[47]

However, more than this—and, indeed, as events in England, where there was no such competition, showed—British sports spectators in the 1930s had the same issues with the American code that the creators of the English code had had fifty years earlier: the game favoured the defending team, and, because of the three-out-all-out rule, play was frequently interrupted. Below is what an admittedly biased sports columnist who watched the game that the RAF St Athan teams played at Mountain Ash in the Rhondda Valley had to say about what he saw:

A crowd of over 500 attended the game. Their interest in the game can be well judged by the fact that 75% of them left the field before the game ended. In my opinion, the game failed hopelessly to “catch on.” The game seemed to lack continuity. Each side batted nine times. Each innings ended when three of the batting side got out. The result was that the game was a sequence of change-overs which detracted from the interest in the play.[48]

The professional Moores American baseball leagues, launched with such fanfare in 1934, flourished only for a couple of years before experiencing contraction, decline, and final collapse—British sports fans just would not adjust to the style of play.[49] The NBA itself would not survive the suspension of its leagues brought on by the outbreak of the Second World War. In England, some of the amateur Moores leagues would reform as independent operations postwar. However, in Wales, only the game under the English code would continue, enjoying what some considered its finest years in terms of the quality of play in the late 1940s and early 1950s. However, after that time, attendance would dramatically decline. Although the game survived all the way into the modern era, the most recent international was held in 2014. Grange Albion, the great survivor, finally wound down in 2018, taking the league with it—although attempts continue to revive the game. In the view of baseball historian and British Baseball Hall of Famer William Morgan (1923—2015), the game was a casualty of the rise of television. [50]

It was with William Morgan that I began this two-part look at the game in South Wales, and it is with him that I will end it. The 1939 Cardiff American League may not have achieved the broad appeal that the NBA had hoped for, but it did excite the interest of at least one Cardiff resident: a 15-year-old William Morgan. He turned out for the Central Y.M.C.A. team in a couple of innings of a preseason warm-up game.[51] This sparked a lifelong interest in the American game, which gave baseball in Britain its first and arguably most important historian. I walk in his footsteps.

Jamie Barras, July 2025.

Back to Health, Friendship, and Baseball

Notes

[1] ‘Cardiff Workers’ Sports Club’, Western Mail, 5 April 1919.

[2] Headquarters versus Crew: ‘U.S. Baseball at Cardiff’, Western Mail, 15 March 1919.

[3] ‘Welsh Baseball Association’, Western Mail, 15 May 1919.

[4] Newport Club first post-war meeting and ban on ‘dolly’ bowling: ‘Baseball’, ‘Baseball’, South Wales Weekly Argus and Monmouthshire Advertiser, 10 May 1919; match against Splott: ‘Baseball’, South Wales Argus, 13 May 1919; Wetter Brothers in the team: ‘Baseball: Newport Club Averages’, South Wales Argus, 4 October 1919.

[5] See list of match results: ‘Baseball’, Western Mail, 30 June 1919. Grange’s return: ‘Baseball: Welsh Association’s Annual Meeting’, Western Mail, 18 March 1920.

[6] ‘Baseball Notes’, South Wales Argus, 17 June 1913.

[7] A summary of these rules changes is contained in: ‘Game All Set for Its 96th Birthday’, South Wales Echo, 15 January 1988. In the latter article, the four runs down to two rule it attributed to 1931, however, the rule is discussed in 1921, here (as a shortlived EBA innovation): ‘Baseball In Wales’, South Wales Argus, 16 July 1921.

[8] ‘Welsh Baseball: Arrangements for this Season’, Football-Argus, 23 April 1921.

[9] ‘Schoolboys League’ and Glamorganshire and Monmuthshire Associations: see Note 8 above; strenthening ties with EBA: ‘Baseball in Wales’, Western Mail, 22 March 1922.

[10] ‘British Baseball Union’, Liverpool Echo, 6 August 1921; ‘Baseball Budget’, Liverpool Echo, 13 August 1921. There is a single mention of the Union the following year, but this may simply reflect a meeting between the EBA and WBU in advance of that year’s International: ‘Baseball Memoranda’, Liverpool Echo, 6 May 1922. The International Baseball Board was founded in the summer of 1928: ‘Baseball Budget’, Liverpool Echo, 30 June 1928.

[11] ‘Baseball Notes’, South Wales Argus, 17 June 1913.

[12] List of teams, dates, and results assembled from: ‘Baseball’, Western Mail, 14 May 1923; ‘Baseball’, Western Mail, 23 July 1923; ‘Baseball: Cardiff Ladies’ League Trophies Presented’, Western Mail, 2 October 1923.

[13] ‘Ladies’ Baseball’, Western Mail, 26 February 1927.

[14] https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-typists-factory-girls-and-clerks, accessed 18 July 2025.

[15] https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/london-stories/munitionettes-womens-football-first-world-war/, accessed 18 July 2025.

[16] Susan Pyecroft, ‘British Working Women and the First World War.’ The Historian, 1994, 56, no. 4, 699–710. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24449074.

[17] Hammerettes: ‘Wasps Poison Potion for the Hammers’, West Ham and South Esesex Mail, 23 July 1937; Honey Bees: ‘Sports Gossip’, West Ham and South Esesex Mail, 28 August 1936.

[18] ‘He Won Girls’ Baseball!’, Daily Herald, 27 August 1931.

[19] ‘Baseball for Girls’, Liverpool Echo, 18 March 1931.

[20] Johnes is one author who mentions this 1926 game: Martin Johnes, “‘Poor Man’s Cricket’: Baseball, Class and Community in South Wales c.1880–1950.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, 2000, 17 (4), 153–166. doi:10.1080/09523360008714152.

[21] ‘To-Day’s Exhibition Game’, Western Mail, 30 June 1924.

[22] Letter, ‘Elaine’s Feat’, South Wales Echo, 10 June 1986. Royle is spelled ‘Royal’ but this seems to be a mistake. The ‘feat’ in question was the scoring of ten home runs (ten fours) in succession by Jubilee Sports player Elaine Cross, a new record.

[23] Information comes from the entry for ‘Hilda Royle’ and ‘Irene Royle’ in the 1921 Wales Survey, Grangestown (West Cardiff) district, ancestry.co.uk, Ancestry.com Inc. Operations, accessed 19 July 2025. The photograph is question is attached to the entry for Hilda Royle (1908-1993) in the Pill Family Tree (Pill was Hilda’s married name).

[24] ‘American Baseball’, Evening News (London), 5 June 1924.

[25] ‘International Baseball’, Western Mail, 3 August 1926. Match on Radio: ‘Wireless Notes’, Western Mail, 24 July, 1926. Baseball Prospects: ‘Broadcasting the Programmes’, South Wales Argus, 1 May 1926.

[26] ‘Splott University Settlement Baseball Club’, Western Mail, 11 May 1928.

[27] Assessment for Listing, Old College Building, Courtney Road, Splott, Cardiff, https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-01/160307atisn10172doc1.pdf, accessed 16 July 2025.

[28] Stratford game: ‘Baseball: Wales Beat England’, Western Mail, 9 June 1924; Tufnell Park game: ‘Baseball: England Turns the Table on Wale’, Liverpool Daily Post,10 June 1924.

[29] Note 14 above.

[30] 1923 international: ‘Baseball: England’s Easy Victory Over Wales’, Liverpool Daily Post, 23 July 1923 1924 international: ‘International Baseball’, Western Mail, 28 July 1924; 1925 international: ‘Bee’s Notes on Sports: Arise, Sir Baseball’, Liverpool Echo, 27 July 1925. Population data: https://web.archive.org/web/20240704043924/https://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/table/EW1921GEN_M13, accessed 19 July 2025.

[31] ‘Harridge and Heydler Have Enough Worries’, Springfield Evening Union, 17 April 1933.

[32] Barbara Clegg, ‘Moores, Sir John (1896–1993), businessman and philanthropist’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 20 Jul. 2025. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-40918.

[33] Reduction in number of officers: ‘Baseball Changed’, Liverpool Echo, 24 October 1931; Bailey and Deakin ousted: ‘Baseball: New Men at the Helm’, Liverpool Evening Express, 19 November 1931; Kennard and Cannell ousted in turn: ‘Baseball Officials’, Liverpool Evening Express, 27 November 1931; EBU formed: ‘New Baseball Union’, Liverpool Echo, 30 January 1932; Kennard and Cannell in new Union: ‘English Baseball Union’, Liverpool Echo, 16 February 1932.

[34] Moores sponsoring EBU trophy: ‘Bee’s Notes on Sports: New Baseball Trophies’, Liverpool Echo, 9 December 1932; Moores as patron of the EBU and travelling to America to promote England, Ireland, America internationals: ‘Bee’s Notes on Sports: Ambassador to America’, Liverpool Echo, 28 March 1933.

[35] Quoted in the Springfield Evening Union piece, Note 29 above.

[36] ‘American Baseball to be Played in Liverpool Next Season’, Liverpool Evening Express, 12 August 1933

[37] https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/artefacts/1937-Challenge-Cup-2022-08-14.pdf, accessed 20 July 2025.

[38] https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-slugger; https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-washington-makes-his-bow; See also: Josh Chetwynd and Brian A Belton, ‘British Baseball and the West Ham Club’ (London: McFarland and Company, 2007); Daniel Bloyce, ‘John Moores and the ‘Professional’ Baseball Leagues in 1930s England’, Sport in History, 27:1 (2007), 64-87. Harvey Sahker, ‘The Blokes of Summer’, (Free Lance Writing Associates, Inc., 2011). William Morgan, ‘History of English Professional Play’, Baseball Mercury, Issue 27, May 1981, https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/mercury.html, accessed 20 July 2025.

[39] ‘R.A.F. Will Get Fit—On Baseball’, Weekly Dispatch (London), 26 April 1936.

[40] Not compulsory: ‘Baseball at Halton’, Bucks Herald, 24 April 1936; Streatham-Mitcham Giants: ‘Showing Him How’ Daily Mirror, 30 April 1936.

[41] Inter-Squadron Baseball’, Bucks Herald, 25 June 1937. Ilford Nomads and No Varys visit: ‘Halton’s Baseball Success’, Bucks Herald, 9 July 1937; ‘60 teams’, etc.: ‘The R.A.F. Men Who Play Baseball’, Evening News (London), 2 August 1937; 1938 Amateur American team visits Halton: ‘Airmen to Test American Baseball Side’, Daily Express, 23 August 1938.

[42] ‘Introducing American Baseball to Wales’, Western Mail, 1 March 1939.

[43] McGraw as organiser of American game in Cardiff: ‘Baseball’, Western Mail, 25 January 1939; Freddie Fish and Cardiff American Baseball League: see Note 40 above; Freddie Fish’s record: ‘Not Seven or Even Nine—It Was Eleven!’, South Wales Echo, 6 January 1986.

[44] This list was assembled from the entry for William Morgan at the British Baseball Hall of Fame: https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/bbhof/index.html, accessed 20 July 2025; ‘Cardiff American League’, Western Mail, 22 May 1939; ‘Cardiff American League’, Western Mail, 29 May 1939. The Balloon Squadron played as the ‘Balloon Barrage’ team, the name of the unit is given here: ‘Baseball: Aberdare Valley Exhibition Game’, Western Mail, 25 May 1939. It should be noted that the BBHoF entry for William Morgan gives the name of one of the teams as ‘Penzance Social Club’, this is, of course, incorrect, it was Penylan Social Club. RAF St Athan winners of the league: ‘Poor Support for Fete’, South Wales Weekly Argus and Monmouthshire Advertiser, 26 August 1939.

[45] Newport game: ‘Somerton Park Novelty’, South Wales Argus, 13 May 1939; Mountain Ash game: ‘American Baseball at Mountain Ash: Some Candid Comments’, Merthyr Express, 3 June 1939; Blackwood game and Hughes MBE: see Note 44 above, final reference.

[46] https://www.ishilearn.com/diamond-lives-slugger, accessed 20 July 2025.

[47] Ted Peterson: https://welsh-sports-hall-of-fame.wales/hall-of-fame/ted-peterson-mbe/; 16,000 at 1948 international: .

[48] See Note 45 above, second reference.

[49] See Note 38 and references therein for the story of the brief success and rapid decline of the Moores professional American baseball leagues.

[50] Last international: Elizabeth Muratore (quoting Gabriel Fidler), ‘Welsh Baseball’s Remarkable History’, https://www.mlb.com/news/featured/welsh-baseball-remarkable-history; Demise of Grange Albion and the league: http://www.grangetowncardiff.co.uk/grangesport.htm; William Morgan, ‘The E.B.A. Game (2)’, Baseball Mercury, Issue 29, February 1982, https://www.projectcobb.org.uk/mercury.html, accessed 20 July 2025.

[51] Note 44 above, first reference.

Women's Footballers, England, World War One. Semi-weekly Tribune, 29 March 1918. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The teams in the 1923 'Cardiff Ladies' League'. Reproduced from the Western Mail, 14 May 1923

The Cardiff and District Ladies' Challenge Bowl, 1923. Results reproduced from the Western Mail, 16 June 1923.

The rather distorted view of the Welsh and English game presented in the US press. San Antonio Light, 31 January 1926. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

American baseball statistics applied to the English and Welsh game. South Bend news-times, 3 December 1925. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

'Cardiff American League', 1939. The American game makes a brief return to South Wales. Reproduced from Western Mail, 12 June 1939.